67 graveshafts of enslaved African Americans were discovered in 2012 during expansion of the graveyard at the University of Virginia

Source: University of Virginia, Unearthing Slavery at the University of Virginia (Spring 2013)

67 graveshafts of enslaved African Americans were discovered in 2012 during expansion of the graveyard at the University of Virginia

Source: University of Virginia, Unearthing Slavery at the University of Virginia (Spring 2013)

Burial sites of the enslaved are scattered across Virginia. Slavery was present across the entire state, and the enslaved were segregated in graveyards as they were in life.

Finding such graveyards is often challenging. Tombstones that mark the graveyards of white people are rare in graveyards of the enslaved. Many graves were marked with just fieldstones, without inscriptions. An enslaved person might have been able to carve the name of the deceased and the date of their death on a stone, but advertising an enslaved person had the ability to read and write might have been risky.

Finding ancient graveyards of the enslaved requires looking for a few aligned depressions in the ground and stones. Such clues are easy to miss, and many former graveyards have been lost to development of modern roads and houses. Archeologists searching for them use local tradition as well as historical documentation to identify a potential site. Ground Penetrating Radar, and stripping off the topsoil to find rectangular patterns of discolored soil, can identify grave shafts.

In some graveyards, fieldstones were carved with curved or triangular tops to mark where individuals were buried at a particular site. Local boulders were carved to identify graves at the Red Hills Plantation in Albemarle County and elsewhere; the enslaved people did not have the option of purchasing granite or marble.

At Monticello, the graveyard includes headstones and monuments for Thomas Jefferson and his white relatives. There were 400 enslaved workers there as well, but only one graveyard with around 40 burials has been identified. Only some are marked, with uninscribed fieldstones, at the site near the David M. Rubenstein Visitor Center.

The burial site of Sally Hemings, with whom Jefferson had one or more children, is unknown. Until 1999, the descendants of Sally Hemmings were not allowed to participate in the annual gathering in the graveyard hosted by the Monticello Association.

The Monticello Association owns the five adjacent parcels, totaling 0.692 acres, that are now Jefferson's graveyard. The group is separate from the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, which owns the grounds surrounding the graveyard and the historic house. All descendants of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings share common ancestry from John Wayles, the father of Jefferson's wife Martha and of Sally Hemmings. However, regular membership in the Monticello Association is restricted to just lineal descendants of Thomas Jefferson through his daughters Martha and Maria.

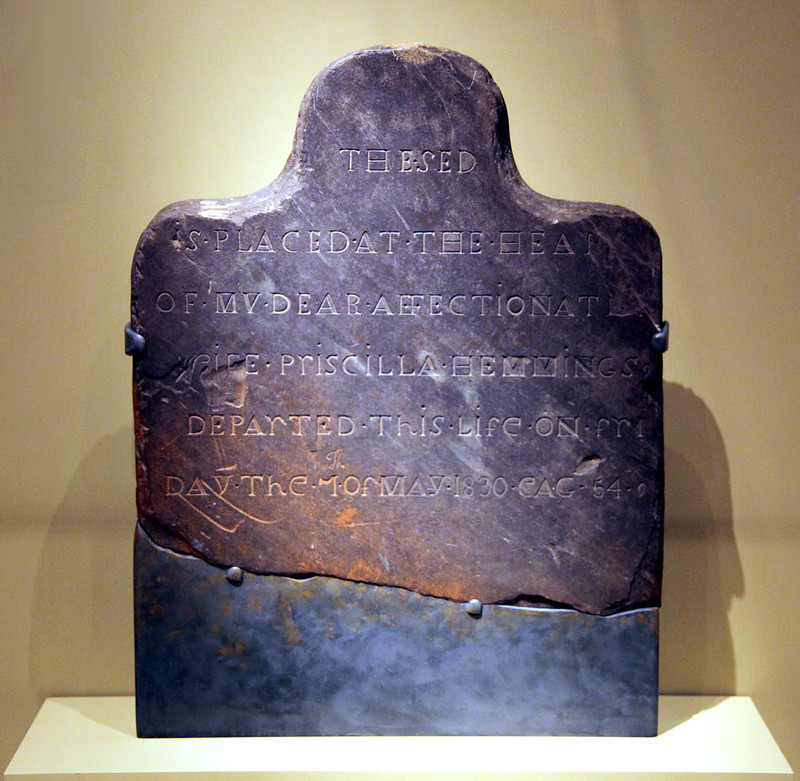

A carved headstone for Priscilla Hemmings, who cared for Martha Jefferson's children when she moved her family to Monticello after her father finished his second term as President of the United States, was found on the grounds on Monticello around 1960. The site of her grave is unknown. It is the only carved marker at Monticello for any of the enslaved people who lived there.1

gravestone carved by John Hemmings for his wife Priscilla in 1830

Source: Tim Evanson, Hemmings slave headstone from Monticello - Smithsonian Museum of American History

When an enslaved person died, the body was buried by other members of the enslaved community unless the deceased was the only person owned on an isolated farm. Some rituals resembled those in white society - members of the family and friends would wash the body, wrap it, and stay with it until placement in the ground. The body was typically placed in a grave with the head to the west. That may reflect Christian more than West African tradition, so when the dead would arise at the Second Coming of Jesus Christ the person would be facing towards the rising son in the east.

There was no embalming, so quick burial was essential. The event would be in the evening; taking time off from work was not an option. A minister would lead the procession, with the body carried in a shroud or coffin, and speak at the grave site.

burials of the enslaved occurred at night, so no work time would be lost

Source: New York Public Library, In the brush; or, Old-time social, political, and religious life in the Southwest (illustrations by W. L. Sheppard, 1881)

The dominant white community restricted gatherings of the enslaved and their ability to community news in order to minimize the opportunity for a slave revolt, so attendance at the burial might be sparse. In some areas a white minister had to conduct the funeral, to ensure adequate oversight of the gathering. A second ritual might be held at the grave weeks or even months later, when the local enslaved community could gather and honor the person.

Music such as drums and words at the funeral of an enslaved person differed significantly from the burial of white people. One report described the more-emotional sharing of grief and life experience:2

graveyards for the enslaved were located in places not suitable for raising crops

Source: Slavery Images, A Plantation Burial (by John Antrobus, 1860)

In areas with a low percentage of people kept in slavery, the dead were buried in small plots or outside the edges of the white family graveyard on a farm. Large plantations had large graveyards dedicated for the everlasting resting place of those freed from slavery by death.

What is now the Belmont Country Club, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute research campus, and Lansdowne on the Potomac were once the Belmont and Coton plantations owned by Thomas Ludwell Lee and Ludwell Lee. The Lee family was part of the gentry who controlled Virginia, and the two plantations were home to some of the largest concentrations of enslaved people in Loudoun County.

Land at what is now the intersection of Route 7 and Belmont Road became the largest cemetery of enslaved people in Loudoun County, where the enslaved at Belmont Plantation were buried.

Pastor Michelle C. Thomas discovered the site existed by researching records in the courthouse. In 2015, the developer of the site (Toll Brothers) responded to her request and donated 2.75 acres to the Loudoun Freedom Center. Creating the African-American Burial Ground for the Enslaved at Belmont ensured the site would be both remembered and protected from disturbance. There were at least 44 graves there. Others may have been removed by construction of a modern stormwater pond and by earlier widening of Route 7.

When her 16-year old son drowned in 2020, Pastor Thomas obtained permission from the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors to bury him at the site of the historic cemetery. He became the first person who was born free to be interred there. A master plan for the cemetery, prepared in 2021, proposed adding 40 more burial sites, a scatter garden and cremation walls, interpretive exhibits, demonstration gardens featuring vegetables that would have been grown on the plantation, a social gathering space with a barbecue area, a schoolhouse, and cabins representing where enslaved people lived.

A data center developer purchased 100 acres next to the cemetery in 2024, paying $1.8 million/acre. The developed offered to donate 10 acres, estimated to be worth $210 million, to provide a trail from the cemetery down to a tributary of Goose Creek - provided a proposed Dominion Energy transmission line was not built through the remaining 90 acres and Loudoun County authorized two new data centers. The proposed Belmont Innovation Campus would expand from 1.3 million square feet to 2.9 million square feet of data center development.

The rezoning proposed routing the transmission line across the 10-acre parcel to be donated. Dominion Energy preferred its original route, saying it minimized impacts to the tributary to Goose Creek and to the cemetery. The data center developer completed a ground-penetrating radar survey of where the 10-acre parcel would be disturbed, finding no graves. The survey suggested that underground rock so close to the surface made it unlike that anyone was every buried there.

The Goose Creek Association and the Belmont Homeowners Association supported the rezoning, in part because it would have protected a 500-foot buffer along Goose Creek as well as donated 10 acres to the African-American Burial Ground for the Enslaved at Belmont. Pastor Thomas also endorsed the data center developer's proposal, even though it would place high-voltage transmission lines closer to the cemetery. She said:3

Rezoning supporters on the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors considered the proposal to be environmentally-friendly. However, a 5-4 majority rejected the proposed rezoning for the data center, the first time the board had declined to support a data center rezoning. One supervisor stated before voting against the rezoning:4

In the end, the data center developer negotiated with Dominion Energy to revise the route of the transmission line and managed to get Loudoun County approval. He then donated 10 acres to the African American Burial Ground for the Enslaved at Belmont, expanding upon its existing three-acre parcel. By then, 130 names of people buried at the site had been identified. Future plans for the burial ground included constructing replicas of the quarters in which enslaved families lived and a three-floor Freedom Center Museum.5

After the Civil War, African-American communities often established new burial grounds associated with their local churches. Former burial sites on old plantation sites were not maintained, and in some cases forgotten. During the Jim Crow era, state and local officials were insensitive to disturbance of such sites during road construction or other development projects.

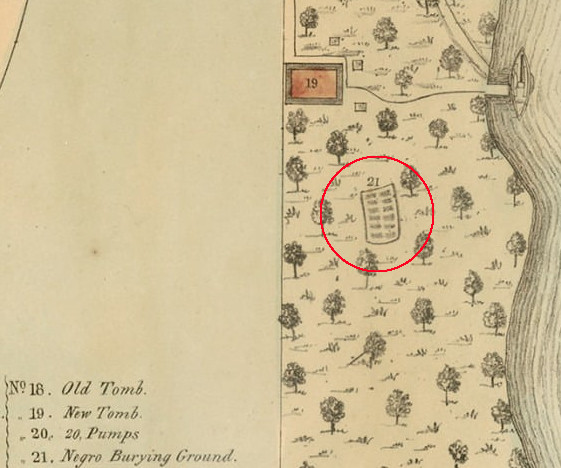

At Mount Vernon, the burial ground for enslaved people was located on a ridge with minimal agricultural potential. A visitor to George Washington's new tomb in 1833 reported:6

at Mount Vernon, the "Negro Burying Ground" was located on a narrow ridge near George Washington's final ("New") tomb

Source: Mount Vernon, Tracing the History of the Slave Cemetery

The Mount Vernon Ladies Association marked the site of the cemetery of the enslaved people owned by George and Martha Washington in 1929. A marble plaque was inscribed with "In memory of the many faithful colored servants of the Washington family buried at Mount Vernon from 1760-1860. Their unidentified graves surround this spot." Mount Vernon believes the marker is the first at an historic plantation to recognize a former slave cemetery.

To archeologists, the site is designated 44FX116. The Mount Vernon Ladies Association, owner of the plantation, called it the Slave Cemetery, but some free blacks were buried there.

No individual burial locations are documented, but tradition holds that among those buried there are William (Billy) Lee and West Ford. George Washington purchase Lee in 1868, and he served as Washington's personal servant (valet) during the Revolutionary War. Lee was the only enslaved person that Washington freed immediately through his will when the former president died in 1799.

West Ford was owned by Bushrod Washington, George Washington's nephew who owned Mount Vernon after 1802. Ford greeted guests, managed some plantation operations, oversaw other slaves, and took care of William (Billy) Lee in his later years. Bushrod Washington freed him around 1805 and, at his death in 1829, gave West Ford 100 acres. That land became the community of Gum Springs in Fairfax County. Ford's burial in July, 1863 may be the last one in the cemetery.

In 1982, the failure to acknowledge the graveyard within the cultural landscape of Mount Vernon drew media attention. The Mount Vernon Ladies Association responded by building a new brick archway, adding a new marker, and incorporating the story of the enslaved at Mount Vernon into the interpretation of George Washington's home. A dedication of the new memorial at the graveyard was held on on September 21, 1983.7

At the University of Virginia, people owned by the school were buried near the base of what became Observatory Hill. The existence of their graves was forgotten until 2012, when the university began to expand the graveyard and add a columbarium. Archeologists discovered the burial sites, the university relocated where it planned to expand, and the existence of the burial sites for the African Americans was marked.

That ended the previous activities outside the walls of the graveyard for white burials. One former student noted:8

Local memory of abandoned cemeteries has led to modern restoration of some. In Shenandoah County near Quicksburg, "Sam Moore s slave cemetery" was identified after a local non-profit organization bought 10 acres that were once part of the Edge Hill owned by Sam Moore. The site was overgrown with vegetation, but depressions in the ground and field stone markers indicated the final resting places of at least 25 people known only by first names. Corhaven, the farm retreat which had purchased the land, marked the graveyard with a rail fence, added wooden benches, and made it a spot for solace and sanctuary.9

In 2015 the Danville-Pittsylvania Regional Industrial Facility Authority purchased the 289-acre site of the Oak Hill plantation, adjacent to the 3,528-acre Southern Virginia (Berry Hill) Megasite planned for industrial development. The plantation was one of many owned by the Hairston family, and some of the enslaved workers buried there were fathered by white Hairstons. The white and black branches of the family have held common reunions and established a clear recognition of their shared history.

The purchased was followed by moving about 275 graves on the site to a new location a mile away, so the land could be developed for attracting new businesses that were compatible with the adjacent megasite. The Hairstons were consulted before the graves were exhumed, and did not organize objections to the reburials. One said:10

Source: Friends of the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, Down By the Riverside: Burial Practices of the Enslaved by Sarah Kohrs

ruins of the quarters for enslaved workers and the plantation house at Oak Hill, built in the 1820's

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Oak Hill