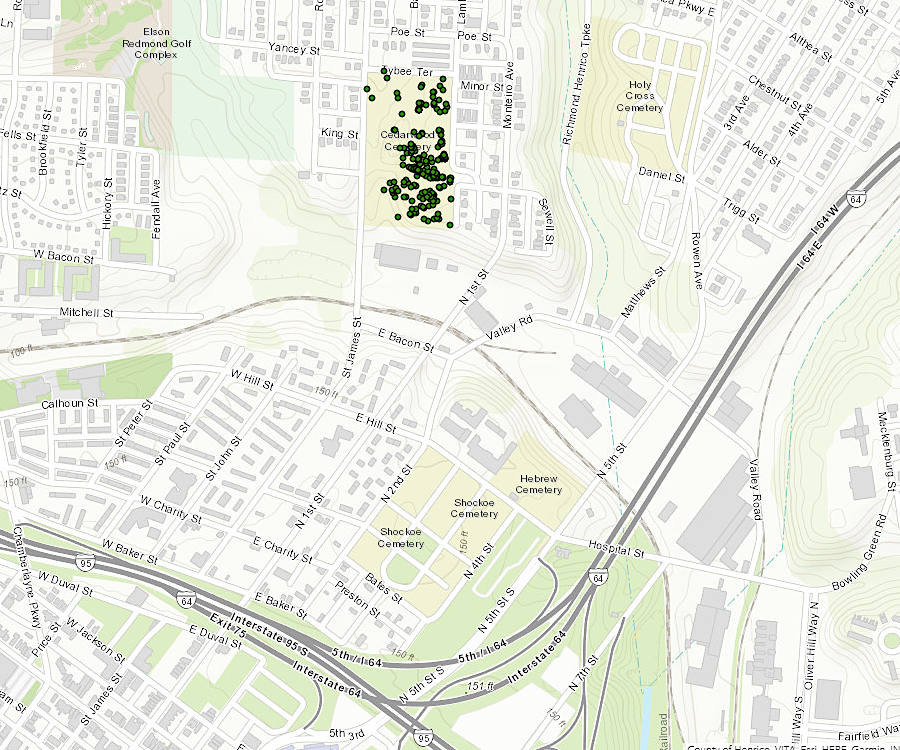

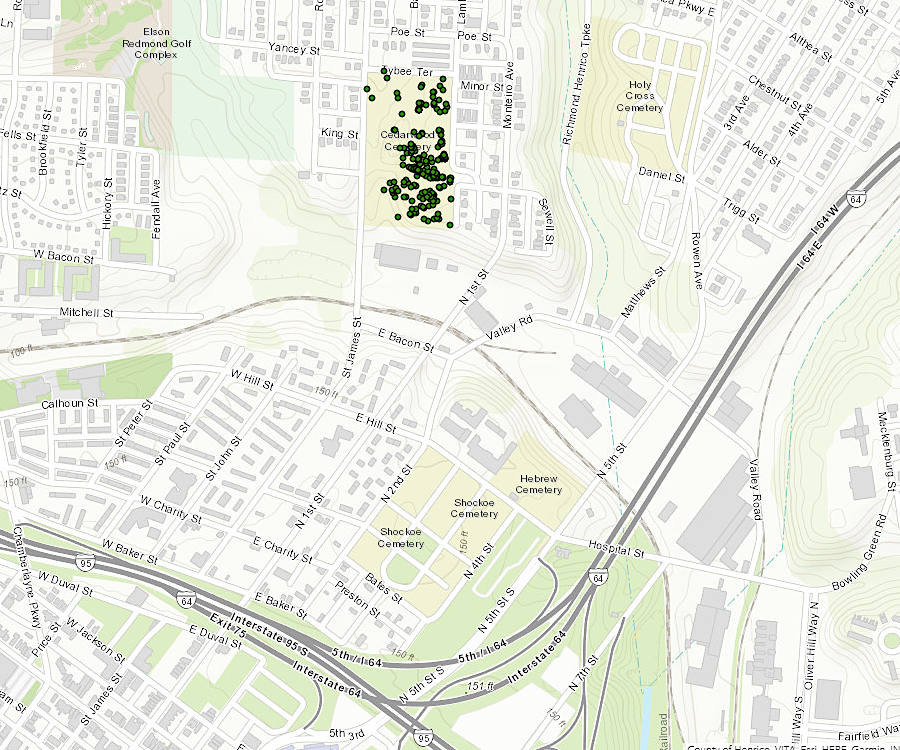

burial sites identified at Cedarwood Cemetery, established in 1816 for enslaved and free blacks in Richmond

Source: University of Richmond, Barton Heights Cemetery Data Collection Spring 2018

burial sites identified at Cedarwood Cemetery, established in 1816 for enslaved and free blacks in Richmond

Source: University of Richmond, Barton Heights Cemetery Data Collection Spring 2018

In Virginia, official segregation extended past one's lifetime into where a person could be buried. There were separate burial sites and cemeteries for white people vs. those considered to be "colored."

Native Americans buried their own in places rarely known to whites. Enslaved African-Americans were interred at sites not suitable for farming, on plantations and farmsteads across the state.

It was rare for those burial sites to be officially recorded. "Headstones" were made of wood or unmarked stones because the friends and families lacked wealth or permission to do more, and evidence of graveyards faded after local communities stopped using them. As a result of forgotten heritage, nearly every modern subdivision could be located on top of a forgotten graveyard.

In a few locations, oral history and scattered documents have preserved the knowledge of the burials of the enslaved. Since the 1990's, such burial grounds have been identified and marked at a few major plantations such as Mount Vernon and Montpelier, while the locations remain just speculative at other plantations such as Gunston Hall.

Free people of color had a greater opportunity to establish formal burying grounds, but in the 1900's many fell into disrepair. Some were completely abandoned, and the land reused for other purposes.

In Richmond, where only whites could be buried around St. Johns Church, city officials created a Burial Ground for Negroes around 1799. It was at the site of the official gallows, on the eastern edge of Shockoe Hill on land not suitable for housing or agriculture. A graveyard at the same place for hanging convicts was a disposal site, not a place of honor.

The community of free blacks created the Burying Ground Society of the Free People of Color of the City of Richmond in 1815, and managed to purchase a separate parcel of land. It was known initially as the Phoenix burying ground, then as Cedarwood Cemetery. Other black groups purchased additional land and established a complex of cemeteries after the Civil War ended slavery. Standard gravestones inscribed with information about the dead date back to 1827.

By the 1880's, there were 12 acres with thousands of burials. City officials banned new burials in 1904, after extension of the streetcar line led to creation of the Barton Heights suburb with white residents. Richmond officially took control over the responsibility for the burial complex during the Great Depression, by which time they had been renamed the Barton Heights Cemeteries.

At the same time the Burying Ground Society of the Free People of Color of the City of Richmond opened Phoenix burying ground, the city stopped using the Burial Ground for Negroes next to the gallows. It purchased two acres, half from burials of the enslaved and half for free blacks. The old Burial Ground for Negroes was used for a school site and jail, before most was destroyed by construction of the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike in 1958.

Historical research starting in 2008 determined that a portion may still exist east of what is now I-95. The Commonwealth of Virginia purchased it in 2011, ending plans of Virginia Commonwealth University to build a parking lot there. Later plans to build a baseball stadium in Shockoe Creek valley threatened it again, but today the historic remnant is recognized as a site to be left undisturbed as redevelopment occurs in the area.1

Norfolk created a "potters field" for the city's poor residents in 1827. "People of colour" could be buried there.

Norfolk established a potter's field in 1827, and allowed "people of colour" to be buried there

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Norfolk and the town of Portsmouth (by Kelly James, 1851)

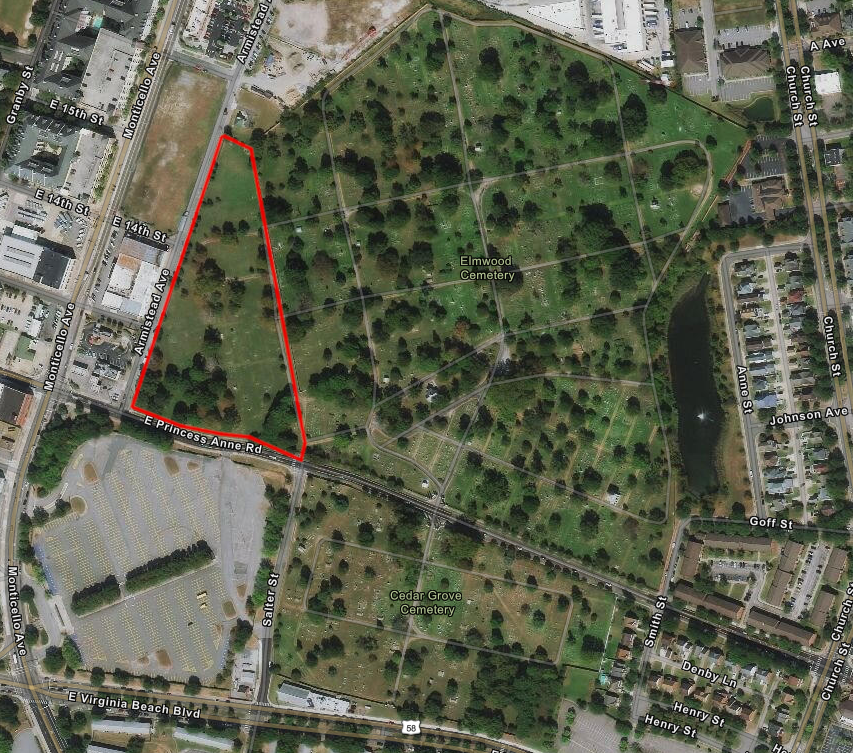

In 1873, city officials acquired land specifically for burial of black residents. The site was adjacent to Elmwood Cemetery, which had been established in 1853 for white residents was and already surrounded with a red brick wall. About 60 Confederate soldiers who had died in the Civil War had already been buried in Elmwood Cemetery, and ultimately 400 Union and Confederate veterans would end up there.

The new site for burial of African-Americans was initially called Calvary Cemetery. It was renamed West Point Cemetery in 1885.

West Point Cemetery in Norfolk is on the western edge of Elmwood Cemetery

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1885, the renaming included a requirement for a portion to be "dedicated as a special place of burial for Black Union veterans." Ultimately 58 African-American veterans were buried in Section 20, plus about 40 African-American veterans of the Spanish-American War.

The Norfolk Memorial Association led the successful effort to erect a statue of Sergeant William Harvey Carney, the first African-American recipient of the Medal of Honor, in 1920. Carney was a member of the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry Regiment. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1900, in recognition of great bravery in the 1863 Union capture of Fort Wagner. The monument was the first monument to black Union soldiers in the south.2

West Point Cemetery in Norfolk has a statue honoring the first African-American recipient of the Medal of Honor

Source: City of Norfolk, View an aerial photo of West Point Cemetery

However, cemetery headstones mark the last resting place of US Colored Troops who served in the Civil War. The soldiers are typically buried in segregated graveyards, such as the Oak Grove Baptist Church Cemetery in York County, but the government-issued Civil War headstones use the same standard design for all soldiers no matter what their race.3

government-issued stone markers were issued for soldiers who served in the US Colored Troops during the Civil War

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Grave Markers for Veterans: Military History in a Rural Cemetery

In 2020, after the death of George Floyd, the City of Norfolk dismantled its monument to Confederate soldiers in the downtown area and decided to move it to Elmwood Cemetery. That would result in the Sergeant William Harvey Carney statue and the "Johnny Reb" statue being in close proximity, together with the graves of Union and Confederate soldiers.4