stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) spread to 92 of Virginia's 95 counties in just 40 years

Source: Digital Atlas of the Flora of Virginia, Microstegium vimineum (Trin.) A. Camus

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Snakehead Fish in Virginia

Native species are those that "belong" here. In normal use, that means the species were in Virginia before the arrival of the Europeans. However, Native Americans imported domesticated dogs and agricultural crops - including tobacco, corn, beans, and squash - long before the Europeans arrived.

Sailors from various nations visited the coastline of Virginia in the 1500's and the Spanish started a settlement in 1570, but the construction of a fort at Jamestown in 1607 is often considered the reference point for defining "native" and "non-native" species.

The balance of nature in the state of Virginia has been tilted by the imported, non-native species. Some were brought here intentionally. Cows, horses, honeybees, pigs, apples, wheat, soybeans, potatoes, and most other agriculturally-valuable species arrived with European colonists. Those colonists expanded production on the corn and tobacco that had already been introduced.

Apples grown in the Blue Ridge and Shenandoah Valley originated in the Caucasus mountains. Wheat, barley, and rye were brought to Virginia from the Fertile Crescent in the modern Middle East. Potatoes came from South America, tomatoes from South America and Mexico, and soybeans from China. Many ornamental shrubs and flowers grown intentionally in yards and gardens are exotic species brought to Virginia from other continents.

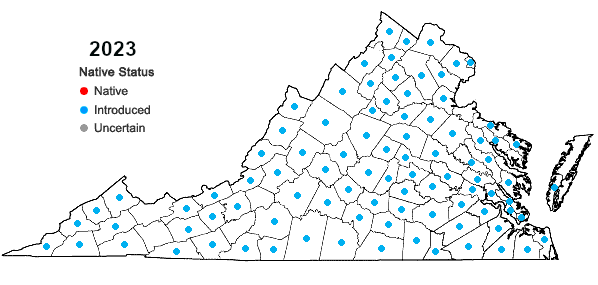

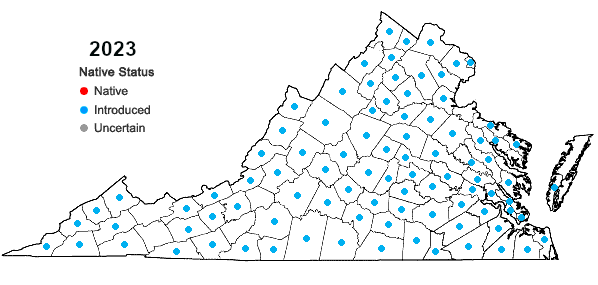

Other species hitchhiked here uninvited, including honeybees, dandelions, Japanese honeysuckle and the veined rapa whelk. Some recent introductions are still expanding their range within Virginia. Red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) are spreading across the southern edge of Virginia. Stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), first found in the United States in Tennessee in 1919 and found in all but three Virginia counties by 2023, was not listed by the 1983 Atlas of the Virginia Flora in any county.1

stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) spread to 92 of Virginia's 95 counties in just 40 years

Source: Digital Atlas of the Flora of Virginia, Microstegium vimineum (Trin.) A. Camus

Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) carpeting the stream valley at Fraser Preserve (Fairfax County)

Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) can sprout on rotting logs

young native willow trees (Salix sp.) can resemble invasive Japanese stiltgrass

Chinese mystery snails (Bellamya chinensis or Cipangopaludina chinensis) and a similar Japanese species (B. japonica) were imported from China to California as a food item soon around the start of the 20th Century. The "mystery" is that young snails appear quickly because they give to live young, rather than lay eggs on aquatic vegetation.

The non-native snails became a popular aquarium species, and appeared in the Potomac River in the 1960's. They are the largest freshwater snails in Virginia, reaching up to three inches in size, so their shells on a shoreline are one of the easiest invasive aquatic species to identify. Like many other invasives, Chinese mystery snails found the climate on the eastern edge of North America to be similar to the climate on the eastern edge of Asia.

Chinese mystery snails thrive in North American habitats that are similar to Asian habitats

Source: sankax, Chinese Mystery Snails (Cipangopaludina chinensis)

Aquatic organisms are hard to see except by anglers and watermen, but quick identification of their presence can minimize the potential expense to eradicate them. The zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) can reproduce and grown quickly enough to clog water pipes. When zebra mussels were introduced into Millbrook Quarry upstream of Lake Manassas, a rapid response eliminated them before they could reach Lake Manassas and obstruct the intake pipes of the City of Manassas drinking water plant.

snakehead fish expanded their known range between 2004-2015, reaching the Rappahannock River

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Mapping Where Snakehead Fish Are Found in Virginia

The flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) is native to drainages in Texas and the Mississippi River watershed. That species was stocked in the James River between 1965-1970 to increase recreational fishing opportunities, and has become an established invasive species.

Blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) are native in the Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio rivers. They were stocked in the Rappahannock, James, and Mattaponi rivers in the 1970's. The assumption that the higher salinity in the Chesapeake Bay would block them from spreading was wrong, and they have invaded the Potomac and other rivers throughout the Chesapeake Bay.

Their appetite for blue crabs and other fish has disrupted the food web; some blue catfish grow five feet long and weigh over 100 pounds. As extraordinarily successful apex predators, blue catfish are threatening the populations of other species. Other than osprey and bald eagles, the catfish have few natural predators. Blue catfish may compose as much as 75% of the total fish biomass in the James and Rappahannock now.

Virginia and Maryland have established an Invasive Catfish Task Force, working with Federal agencies, academics, and non-government stakeholders. The best strategy identified to date to control the population of non-native catfish is to encourage recreational anglers to catch them and to support a commercial fishery.2

electrofishing in the James River allows biologists to estimate the population of blue catfish

Source: Flickr, Monitoring invasive blue catfish in the James River (Chesapeake Bay Program)

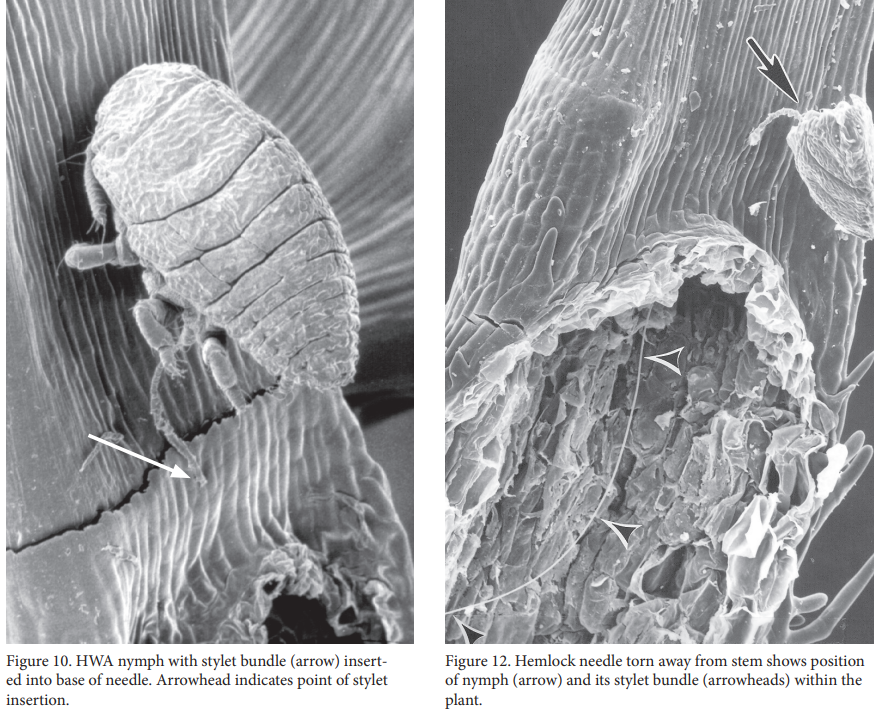

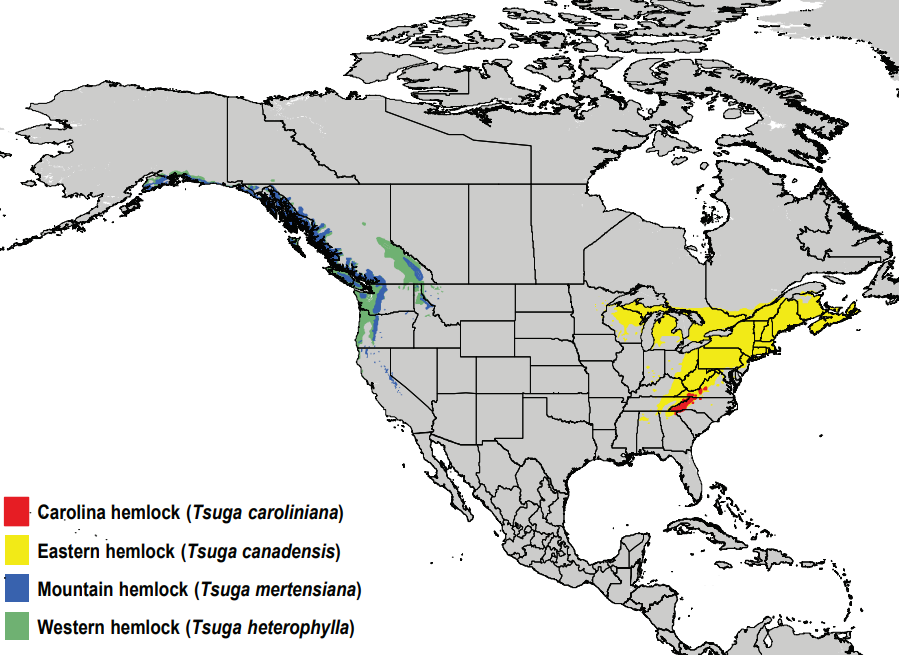

Hemlock trees (Tsuga canadensis and T. caroliniana) are at risk of being extirpated in Virginia by the invasive hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae). In its flightless form, the aphid literally sucks the juices out of the tree. The mass of adelgids in white, wooly nests underneath hemlock branches slowly divert the nutrients in the tree's xylem ray parenchyma cells, starving the tree.

The adelgids reproduce asexually on hemlock trees and create two forms of young. One form remains feeding on the hemlock, while the other transforms into a tiny winged fly. In their native Japan, the winged flies would land on a Tiger tail spruce tree (Picea torano) and reproduce sexually there. The Japanese hemlocks and spruce have evolved adequate resistance to withstand the damage cause by the feeding of the hemlock woolly adelgids,

Picea torano is not present naturally in North America, so the winged adults in Virginia all die. However, enough asexual reproduction occurs for the adelgids to stay continuously on a hemlock tree in Virginia until it dies.

Similarly, the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) has killed over 40 million ash trees in North America. The larvae eat the inner bark, interrupting the flow of water and nutrients.3

non-native insects which arrive without normal predators, such as the hemlock woolly adelgid, can threaten the continued existence of native species

Source: Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Dead Eastern Hemlock trees in Shenandoah National Park, Virginia (by Alexandra Fries)

the hemlock woolly adelgid inserts a tube into the hemlock tree's needle and extracts nutrients from the xylem ray parenchyma cells

Source: US Forest Service, Biology and Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Figures 10 and 12)

in Virginia, Tsuga canadensis and T. caroliniana are at risk of extirpation because of the hemlock woolly adelgid

Source: US Forest Service, Biology and Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Figure 3)

Some of our most common plants and animals are not native. The "English sparrow" pecking away at the crumbs outside McDonalds, the starlings feeding in a flock at the edge of an open field, the Japanese honeysuckle vine climbing along the fence line, the blue flowers of chicory along sidewalks - none of them are native to Virginia. They are aliens, imports from outside the state.

chicory (Cichorium intybus), native to Europe, is now naturalized and thrives in disturbed sunny spots throughout Virginia

The tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima) is a non-native invasive species in Virginia. Volunteers seek to eradicate it from parks, wildlife refuges, and other places designated for conservation of the natural environment. However, species in the Ailanthus genus were growing in Virginia during the Miocene and Eocene epochs over two million years ago. Glaciation exterminated the tree-of-heaven, ginko, and dawn redwood trees from North America, but they survived climate change in East Asia.

Since the beginning of European colonization about 5,000 species have been naturalized across North America. There are 606 documented naturalized species in Virginia:4

the tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima) was native in Virginia back in the Miocene epoch over two million years ago

Source: NatureServe, Tree-of-heaven

Non-native species (including Homo sapiens) may be different and late arrivals, but their value is a judgement call. Species that were not in Virginia at the time of human settlement are considered by many naturalists to have less ecological value. Insects and other animals evolve in synch with plants, and adding a non-native species disrupts the natural pattern. Without a natural predator, spongy (formerly "gypsy") moths (Lymantria dispar) can defoliate trees and alter the species composition in a forest. The fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans can infect bats, causing white-nose syndrome. That disease has dramatically reduced the populations of hibernating bats in Virginia.

The Clematis growing wild at Aquia Landing park in Stafford County smells wonderful - but it is a non-native species. The native version is an equally-pretty climbing vine with a white flower, but it lacks the perfume of the non-native species. The hydrilla that is expanding along the bed of the Potomac may clog the channels into marinas. Still, it is clearly serving the function of submerged aquatic vegetation, trapping silt and providing a place for invertebrates to grow.

Not all non-native species are invasive. Some do not spread beyond where they are planted, and others are minimally invasive. Corn, wheat, and soybeans do not grow in pastures or forests; those species require human care. Daffodils and periwinkle are non-native indicators of old homesteads, but do not spread wildly into nearby habitats.

daffodils are not a native species, but rarely expand beyond where they were planted

Some non-natives are harmful, however. Purple loosestrife and Phragmites spread throughout Virginia wetlands, displacing native species that the animals have used as food sources. The non-native species, while large and "showy," do not provide the same food value to the animals in the area.

The native critters are unfamiliar with the non-native plants, and do not utilize their biomass effectively. Plants and animals that have evolved together create a web of life which adapts gradually to change. As a result, the exotics - in these two cases, invasive species that spread rapidly - reduce the health of the native animals in the wetlands.

Asian ornamentals planted in suburban yards offer no food for native animals. Leaves of crepe myrtle trees rarely show any bites from insects; in the food web, those trees are as useless as asphalt pavement for the production of caterpillars needed by birds.

The Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana), especially the Bradford cultivar, was bred to be sterile. However, various cultivars were able to produce fruit and the species has now become a widespread invader growing in old fields. The tree was bred to have an impressive display of flowers, and now the fertile trees produce an impressive amount of fruit with seeds. The Callery pear now is crowding out native species that are the normal source of food for native birds and other animals.5

unchewed leaves of non-native crepe myrtle trees (Lagerstroemia indica) show they offer no food value for insects

Source: Wikipedia

Other non-native species in Virginia include carp, feral pigs at Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, mute swans in the Chesapeake Bay, and Sitka deer at Assateague Island.

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Virginia Invasive Species Council

Wildlife agencies claimed in 2022 to have successfully eradicated nutria (Myocastor coypus) from the eastern side of the Chesapeake Bay. Nutria had been introduced to the Delmarva area in the 1940's, raised for fur and meat. Escaped and released nutria had no natural enemies in the bay and nutria bred three times a year, so the population soon exploded in the wild.

The muskrat-like nutria damage natural marshes by eating not just the top of vegetation, but also digging out the roots and stems. At Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, 5,000 acres of marsh were transformed into open water or "a field that's been hit by a rototiller." As a consequence, the population of marsh-dependent species dropped precipitously.

Eradication involved trapping 14,000 nutria between 2002-2015. After most nutria were trapped, the remainder were found by capturing a few, placing tracking collars on them, and finding the remainder of the population when the gregarious animals gathered together.

The nutria removal project cost $30 million, and is still not completely successful. Because nutria are still present on the western side of the Chesapeake Bay in Tidewater Virginia marshes, biologists constantly monitor the marshes on the eastern side of the bay to prevent a reintroduction.

The manager of the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge noted the value of removing all the nutria in order to protect the marshes:6

nutria have been eradicated from the eastern side of the Chesapeake Bay, but some still remain in Virginia's Tidewater marshes

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Nutria

About 1/3 of the earthworms in the United States are invasive. The non-native species probably were introduced by Europeans when they first brought ships with ballast; eggs were in dirt on the stones in the bottom of the ships. Today the invasive species are dominant in soils that were covered by the ice sheet until 18,000 years ago, which eradicated the native earthworms.

The common red worm (Lumbricus rubellus) used for fishing bait is not native to North America. Though gardeners equate the presence of earhworms with healthy soil, "...not all earthworms are the same." Introduced species of earthworms tend to consume the litter on the surface, rather than burrow into the soil like the indigenous species. The removal/reduction of the litter layer exposes tree roots and increases the mortality of trees, especially sugar maples (Acer sacharrum). Orchids are impacted as the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of the soil are changed.

Invasive earthworms are also reducing the diversity and abundance of invertebrates in forests with broadleaf trees. Salamanders find less food, since earthworms are competitors.

Prescribed fire might offer one way to control the spread of earthworms in grasslands and potential in forests. The reduction of adults and elimination of litter as a source of food may provide only a temporary impact, if the cocoons (egg casings) in the soil can survive the brief moment of heat as fire sweeps across the landscape.

"Jumping worms" arrived from Japan and Korea (Amynthas agrestis, A. tokioensis and Metaphire hilgendorfi) about a century ago. Their name comes from their thrashing behavior like snakes, which made them a popular fish bait. Recently, anglers have spread them much further across North America. They have also been sold as worms for making compost.

Jumping worms can consume almost all of the layer of leaf litter in just one year:7

the common earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris) is a non-native invasive species

Source: Wikipedia, Earthworm 01.jpg

The spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) is from China, and its primary food is the "tree of heaven" (Ailanthus altissima) from the same area. The insect also feeds on grape vines, hops, fruit trees, and other plants. By sucking out plant juices and facilitating the growth of sooty mold, the rapid spread of that non-native species threatens major agricultural products in Virginia.

The first sighting of spotted lanternflies was at a stoneyard near Winchester in 2018. The site was being monitored because the pest had been found first in 2014 at a stone importing business in Pennsylvania, and it regularly shipped products to the Winchester site.

Egg masses as well as dead adults were found on ailanthus trees in Winchester rather than in a shipment of stone, indicating the species had become established at one site in Virginia. Using the authority in the Virginia Tree and Crop Pests Law, the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services imposed a quarantine for Frederick County and the city of Winchester on May 28, 2019.

Businesses were required to complete training to spot the invasive pest, and to obtain a permit to ship outside the quarantine zone any articles that were considered a risk for lanternfly dispersal. Those articles included lumber, stone, stone, shipping containers, outdoor household articles such as grills, and recreational vehicles. Virginia officials did not go so far as to create inspection stations on I-81, however.

spotted lanternfly

Source: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), Spotted Lanternfly Photo Gallery

Lanternflies are poor fliers, traveling just short distances. A state official said:8

As spotted lanternflies were discovered in new places, the state expanded the quarantine in 2021 and again in 2022 to include 22 counties and cities. In 2025, the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services determined that the quarantine had failed and eliminatedthe Virginia Spotted Lanternfly Quarantine Zone. By then the non-native planthopper was found in 67 Virginia jurisdictions, spread primarily by traveling on railroad cars.

The population of the spotted lanternfly is expected to peak after about five years. After an initial period of heavy infestation, the population of the invasive pest was predicyed to plateau and then decline. At a stable level, it was still likely to be a nuisance and require extra insecticide sprayings in vineyards.

Repeal of the quantine revealed that initial fears of severe economic impact by the spotted lanternfly (SLF) were overstated:9

the quarantine established in 2019 to control spread of the spotted lanternfly failed, and was dropped in 2025

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS), Map of Spotted Lanternfly Quarantine in Virginia (July 2022)

Natural range extensions will occur as the climate changes. Coyotes have recently arrived in Virginia, along with the Nine-banded Armadillo. Alligators, currently found in North Carolina, could naturally occupy Dismal Swamp and the Northwest River/North Landing River in southeast Virginia as winter temperatures rise.

There are nine native species of lizards in Virginia. The pattern of sightings of three additional species of lizards reveals they were introduced via the pet trade, sold as chameleons, and hitch-hiked on plants. The Mediterranean house gecko is now common in urban areas, while Italian well lizards arrived in Northern Virginia after 2010. By 2020, juveniles of the green anole lizard were being found in Virginia Beach. That non-native species was able to adapt and start breeding.10

Virginia has exported invasive species as well as become host to them. In Puget Sound, populations of cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) are treated as an invasive species which the State of Washington's Department of Agriculture will eradicate. That state's Noxious Weed Control Board also has declared cattails (including the Typha latifolia commonly found in Virginia's wetlands) to be a noxious weed that should be eliminated.

cattails (Typha latifolia) are a common wetland species in Virginias, but considered a noxious weed in the State of Washington

Source: Plants of Louisiana, Typha latifolia

A blue crab population became established in the Mediterranean Sea in 2012, presumably transported as larvae in a ship's ballast water. The ship could have acquired the larvae in New Orleans, Norfolk, or perhaps New York, since the crab's natural range is from the Gulf of Mexico to New England.

There were no natural predators in the Mediterranean for blue crabs. They displaced native species, as well as fouled European fishing nets. By 2023, the omnivorous blue crabs had reduced the Italian harvest of clams, mussels and oysters by 50%.

Officials in Ireland became alarmed in 2021 when a dead blue crab was discovered on an Irish beach. An official at the National Biodiversity Data Centre in Waterford, Ireland, commented:11

blue crabs are native from the Gulf of Mexico to New England, but are an invasive species in Europe

Source: Flickr, Callinectes sapidus (blue crab) (Cayo Costa Island, Florida, USA) 1 (by James St. John)

By definition:12

The General Assembly established the Invasive Species Working Group in 2009. The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation maintains the official Virginia Invasive Plant Species List. In 2024, the state agency added 13 more species, growing the total to 103. Species are ranked by high, medium, and low invasiveness:13

The list of invasive species has no regulatory authority, but is useful in educating residents regarding what plants and animals are threats to Virginia ecosystems. State and local agencies are encouraged to use native species for landscaping and habitat restoration projects, and to avoid those species identified as invasive. Training offered by Virginia Cooperative Extension to Master Gardener groups highlight the benefits of native species and the risks of adding invasive species in the landscape.

butterfly-bush (Buddleja davidii) was added to the Virginia Invasive Plant Species List in October, 2024

Source: Master Gardeners of Northern Virginia, Butterfly Bush (Buddleia davidii)

The Virginia Native Plant Society has been particularly engaged in educating gardeners and naturalists regarding what plants are inappropriate to purchase from nurseries, which are still legally allowed to sell invasive species such as Nandina (Nandina domestica). The group has lobbied the General Assembly to require retailers selling plants on the Virginia Invasive Plant Species List to include conspicuous signage that identifies the plant as invasive and includes the words:14

In 2024, the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services had a budget of $660,000 to manage two programs to control invasive species. The state agency reported using its funding to treat approximately 3,500 mounds of imported fire ants and to eliminate two-horned trapa from approximately 62 privately owned ponds.15

In addition to the list of invasive species maintained by the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS) keeps a list of official noxious weeds:16

According to the Code of Virginia, noxious weeks are categorized in three tiers:17

Nandina (Nandina domestica) is an invasive evergreen shrub that is still sold to gardeners by nurseries

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), 13 species added to Virginia Invasive Plant Species List (October 8, 2024)

in January 2020, Japanese stilt grass dominated the Russia Branch floodplain in Blooms Park (City of Manassas Park)

Millbrook Quarry west of Haymarket, where zebra mussels threatened Lake Manassas

Source: Historic Prince William, Aerial Photo Survey 2019