Buchanan County wants mature bull elk with antlers to become a tourist attraction

Source: Wikipedia, Elk

Buchanan County wants mature bull elk with antlers to become a tourist attraction

Source: Wikipedia, Elk

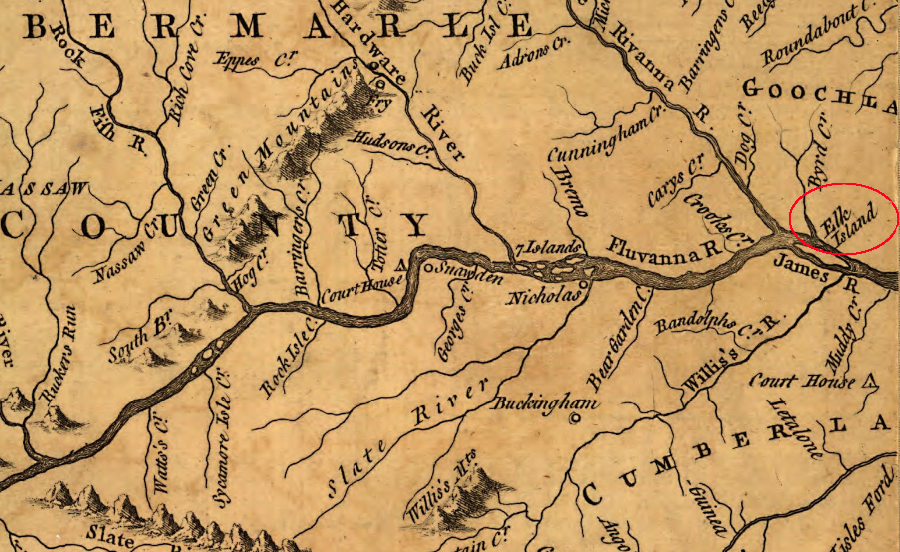

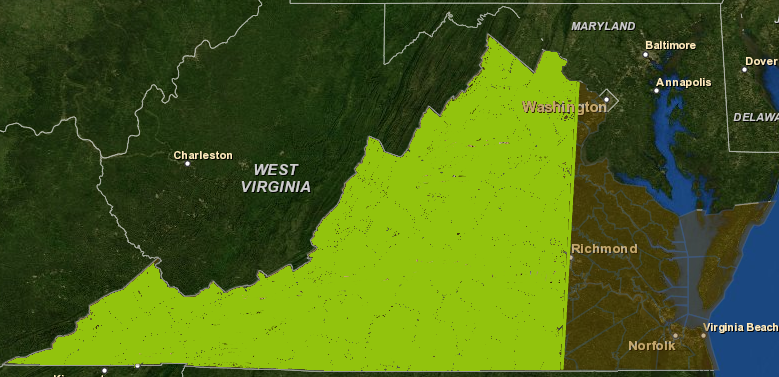

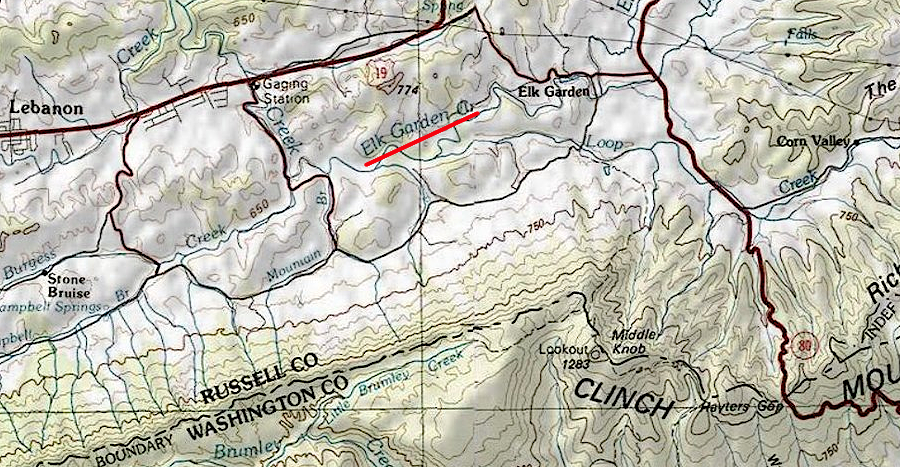

Elk (Cervus elaphus) once grazed in Virginia east to the Fall Line. There are multiple places in Virginia with "elk" in their name, reflecting the historical presence of the large animals.1

place names such as Elk Island in Goochland County offer a clue about the historical range of elk in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia

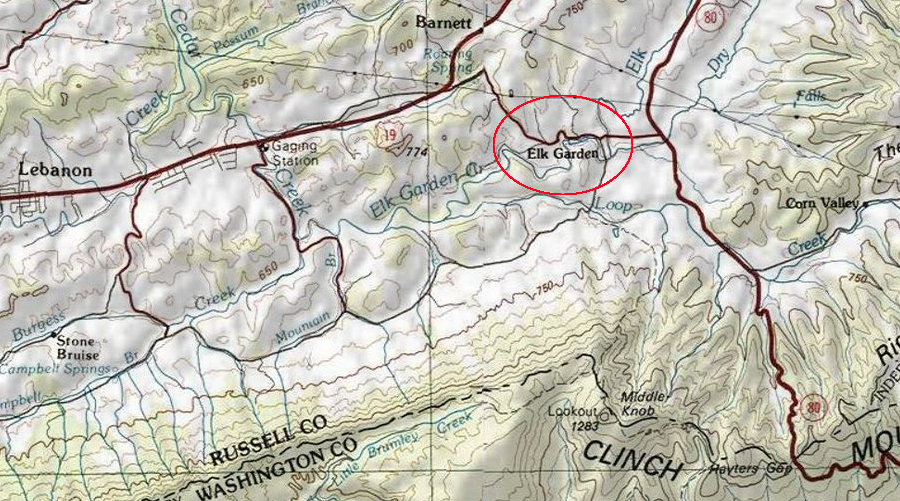

Elk Garden in Russell County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The last native elk was killed in Virginia in 1855, before the Civil War. The original subspecies (Cervus elaphus canadensis) disappeared from Virginia and from other eastern states for two reasons:

1) hunters killed mature elk for hides and meat faster than the animals could reproduce

2) elk lost winter grazing habitat, as valley bottomlands were converted into farms and ranches

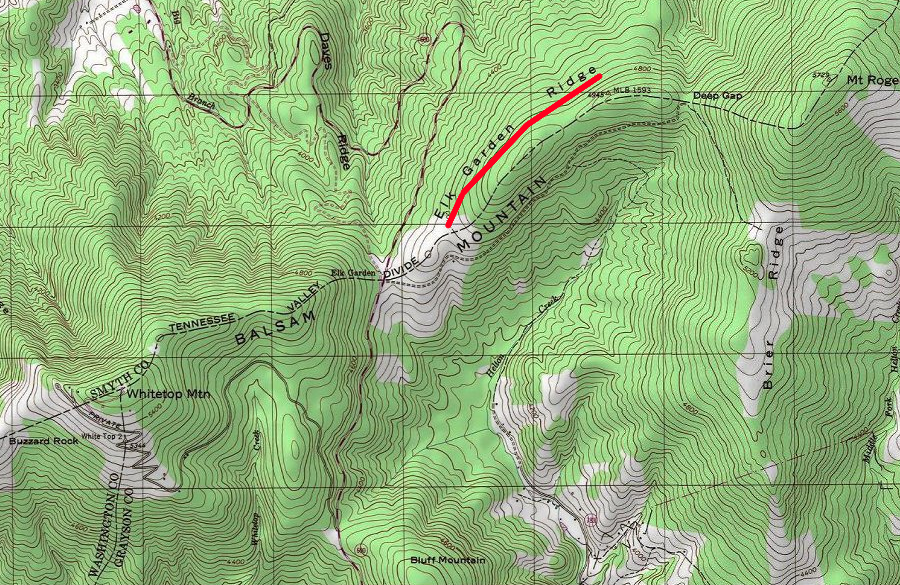

Elk Garden Ridge, on the border of Smyth/Grayson counties near Whitetop Mountain

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The last elk in Virginia was killed in Clarke County, and for nearly 60 years there were no elk living naturally in the state. No elk survived in neighboring states either, so there was no natural migration back into Virginia. Reintroducing elk required capturing the animals west of the Mississippi River, and shipping them east.

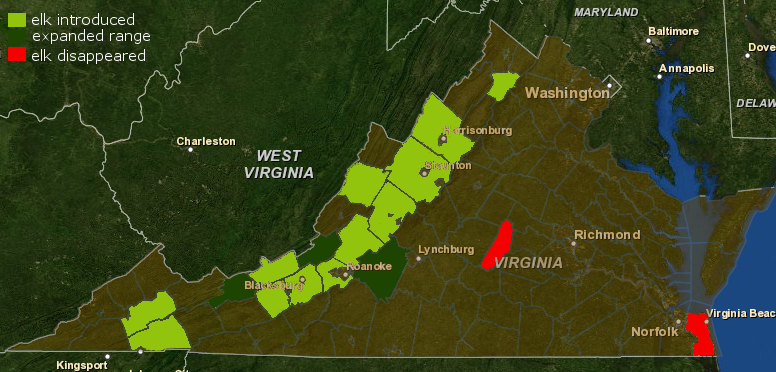

Between 1913-1922, elk were imported and released in Augusta, Bath, Botetourt, Cumberland, Giles, Montgomery, Princess Anne, Pulaski, Roanoke, Rockbridge, Rockingham, Russell, Warren, and Washington counties. Most releases occurred in 1917, when the state imported 125 Rocky Mountain elk from Yellowstone National Park.

The elk released in the sand dunes near Cape Henry discovered the local vegetable farms, so the herd in Princess Anne County (now the City of Virginia Beach) was destroyed soon after release. By 1922, there were none left in Cumberland County either, but elk did expand their range into Bland, Craig, and Bedford counties.2

despite reintroduction in Princess Anne and Cumberland counties, the only population of elk to survive east of the Blue Ridge after 1926 was in Bedford County (where elk migrated across the mountains)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Public support for controlled hunting seasons increased in the 20th Century, but poaching and over-hunting affected the first elk restoration effort that started in the early 1900's. Five years after the 1917 re-introduction, the Virginia Game Commission authorized elk hunts. Re-introduction was intended to create hunting opportunities for recreation, but hunting was permitted in part to accommodate farmers upset at crop damage. Elk ate more than just natural vegetation; planted crops also became a meal.

Back in the 1600's, elk could graze in the summer on mountain ridges and winter in the valley bottoms; long-distance migrations comparable to bison moving acrosss the Great Plains were not necessary. By the 1900's, the habitat on the ridges was still available, but the valley bottoms had been converted into farms and ranches. Elk which moved into the valleys in the winter became, in the eyes of local farmers, large pests.

The lack of winter grazing habitat, plus excessive poaching, resulted in disappearance of the elk imported by the Virginia Game Commission except in two locations.

After 1926, only the two herds in Giles/Bland and in Botetourt/Bedford counties survived in the wild. To supplement their populations in 1935, more elk were imported from Yellowstone National Park.

According to one report:3

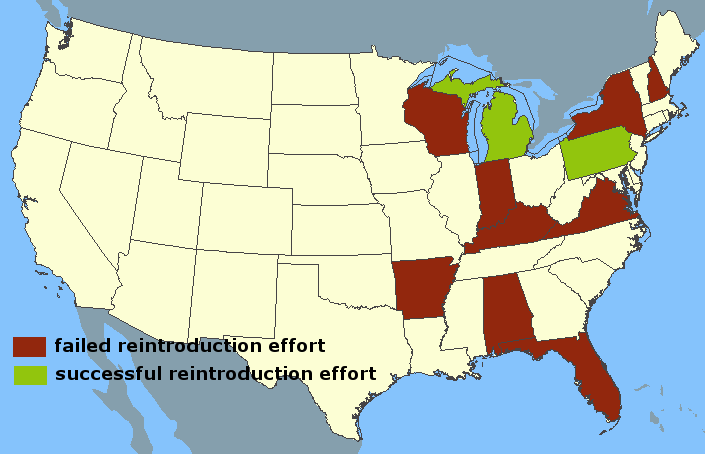

The state stopped authorizing elk hunting in 1960, but wild elk disappeared again from Virginia. Efforts to re-introduce elk prior to 1980 to other eastern states also failed; only Michigan and Pennsylvania managed to establish herds.4

most states, like Virginia, failed to reintroduce elk successfully prior to 1980

Map source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas

In addition to the elk brought to Virginia by the Virginia Game Commission for release into the wild, the wealthy owner of Bellwood Farms south of Richmond imported a pair of elk at the same time. The resulting novelty herd became a popular tourist attraction in central Virginia. It still remains there despite conversion of the farm into a warehouse/distribution center at the start of World War II.

The family sold the farm to the US Army in 1941 so it could create Bellwood Depot - officially konwn as Defense Supply Center Richmond. Before selling, the family got a "gentleman's agreement" commitment from the US Government to maintain the herd. Today, the US military is still maintaining an elk herd there.

There have also been other private herds, such as one owned by entertainer Arthur Godfrey north of Leesburg from the late 1940's-1979. None have lasted as long as the Bellwood elk.5

in 1953, the Saturday Evening Post highlighted "The Elk That Joined the Army" at Bellwood Depot

Source: Defense Supply Agency, The Bellwood Elk

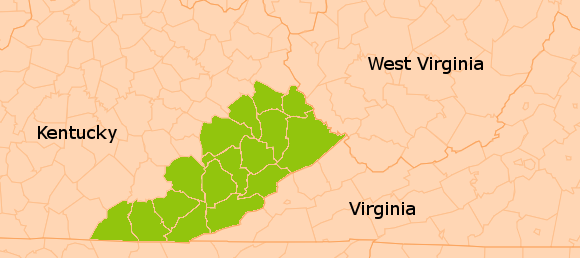

For almost 30 years there were no wild elk in Virginia. Starting in the 1990's, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation initiated the current efforts to re-introduce elk to eastern states. Between 1997-2002, with funding provided by the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, the Kentucky Fish and Wildlife Commission released 1,500 elk on the Cumberland Plateau of eastern Kentucky.

The Kentucky herd grew faster than expected, and biologists discovered that the Rocky Mountain subspecies had sufficient resistance to the meningeal worms ("brainworm" parasites) that are endemic among white-tailed deer in the eastern states. There were few natural predators (hunting was not authorized for the first four years after re-introduction), and winters were mild compared to the western states where the elk had been captured. Reclaimed coal strip mines created artificially-fragmented forests with grass-covered fields that offered extensive grazing habitat, plus early-succession"edge habitat" providing shrub/tree branches for wintertime grazing.

Perhaps most importantly, owners of the old coal mines supported re-introduction. Habitat was better on the other side of the state, but the Kentucky Fish and Wildlife Commission considered concerns of the Kentucky Farm Bureau as well as biological factors when choosing where to reintroduce the species:6

elk lived throughout Virginia, west of the Fall Line, in 1600

Map source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

area occupied by elk in Virginia between 1855-2012: none

Map source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

elk were re-introduced to Buchanan County in 2012-2014

Map source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

As the Kentucky elk population began to expand, some "interstate elk" began to wander into Virginia. The first one traveled to Grundy in 1998, just a year after the initial reintroduction in Kentucky. After efforts to trap and re-locate it back to Kentucky failed, that animal was killed. Ranchers and farmers in southwestern Virginia feared elk would introduce disease to local cattle herds and destroy haystacks, so the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries authorized hunting elk as if they were deer, to prevent a population from growing until a reintroduction policy was adopted.7

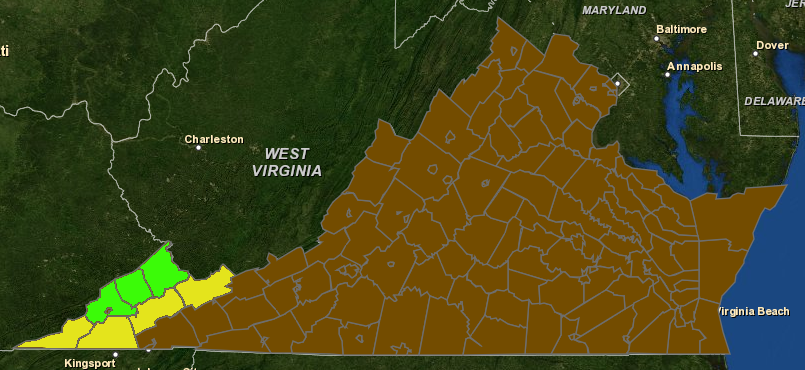

Kentucky selected 16 counties for its elk restoration zone, and ignored objections from Virginia that releases would be too close to the border

Map source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

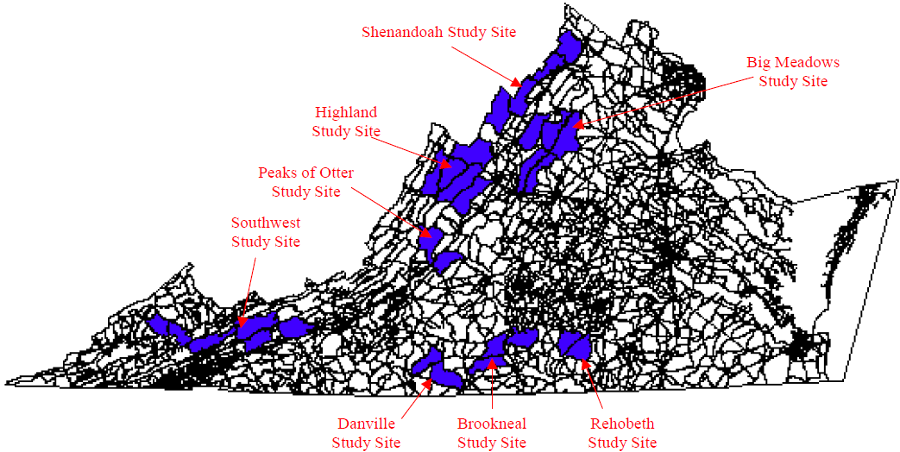

A Masters thesis by Julie A. McClafferty at Virginia Tech, completed in 2000, created a Habitat Suitability Index (HSI) model and identified eight places in Virginia with biological potential for establishing self-sustaining elk herds. That study screened the state to find areas with least 120,000 acres of suitable habitat with a minimal number of 4-lane highways, because traffic on Virginia roads would block elk normal migration between summer/winter range.8

With the encouragement of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, in 2010 the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries explored three main alternatives for elk management:

- "no action" (allowing elk to walk across the Kentucky-Virginia border and naturally reintroduce themselves, but with no objective of maintaining a stable population)

- "passive restoration" (allowing natural migration, but with a population goal of 1,200 elk)

- various forms of "active restoration" (involving capture of elk and release in Virginia at locations where one or more herds could be maintained)

of eight locations identified in 2000 as suitable habitat biologically, only southwestern Virginia was suitable sociologically

Source: Julie A. McClafferty, Location and physiographic relationship of potential elk habitat study sites in Virginia (Figure 2-7)

The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries supported active restoration, and planned to release 200 elk per year for three years to establish a single herd that would expand naturally to 1,200 animals. Though southwestern Virginia did not rank the highest on the Habitat Suitability Index (the Highland study site was most feasible), the state determined that a free-ranging elk population would not be suitable outside of the Appalachian Plateau counties adjacent to Kentucky. Farmland was minimal there, and hunting and wildlife-viewing tourism was predicted to bring some economic benefits to a region of the state that traditionally struggled to provide enough jobs to retain its graduating students.

The Shenandoah Valley offered excellent elk habitat, but reintroduction there would create far too many conflicts with agricultural operations. As the state described the choices:9

Virginia officials considered reintroducing elk in counties on the Appalachian Plateau counties (green) and in the Valley and Ridge (yellow)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

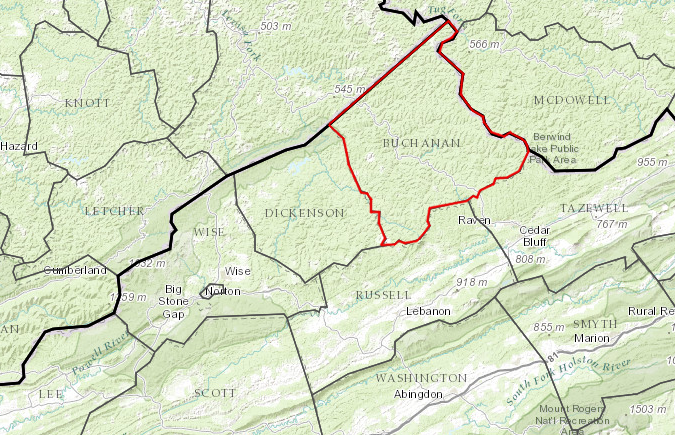

When the state proposed in 2010 to bring elk into Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise, opposition from the Virginia Farm Bureau was clear. Farmers feared damage by elk pushing through fences, eating hay, and introducing tuberculosis or brucellosis (a disease that causes cows to abort) into local cattle herds. Though Bedford County was far from the proposed release site, the agricultural economic development committee there got the Bedford Board of County Supervisors to oppose any elk re-introduction far away in southwestern Virginia.

In 2010, the headline above a Bluefield Daily Telegraph story was "Supervisors: Elk unwelcome in Tazewell." A farmer in Tazewell County (who was far more likely than any Bedford County farmer to be impacted by the elk) said:10

some farmers fear natural elk reproduction will create more animal damage control headaches

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Cow elk and young

After Wise and Dickenson county officials joined the opposition, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries determined that only 75 elk would be released, the final population goal was lowered from 1,200 to 400 animals, and elk would be reintroduced in only Buchanan County. Between 2012-2014, Virginia successfully trapped 70 elk in Kentucky and released them all near Vansant in Buchanan County.

In its effort to expand the number of elk in the county and create economic benefits from wildlife-watching tourism, in 2007 Buchanan County established a local ban on hunting elk despite state objections. Once elk were reintroduced, the state wildlife agency banned elk hunting in Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise.11

Elk Garden Creek in Russell County, where elk once grazed

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

An effort to expand the ban and end elk hunting in Tazewell, Lee, Russell and Scott counties failed in 2013. Farmers successfully advocated for continuing the opportunity to hunt elk during deer season, with each elk counting towards the bag limit for deer. County supervisors in Tazewell, Lee, Russell and Scott counties had opposed the original reintroduction plan in 2010, and considered the proposed ban on elk hunting to be a "back door" expansion of the reintroduction effort.12

Hunting of the elk in Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise counties will be permitted once the population reaches the goal of 400. By 2014, the original 70 imported elk had grown to 90, thanks to the birth of 20 calves that summer.13

By 2019, there were over 250 elk in Virginia. Two years later, the population was estimated at greater than 275.

That growth came in part because no hunting was authorized, but poachers still killed elk. Conservation Police Officers (game wardens) caught one who had used a .22 rifle with a laser sight to kill four elk, plus deer, bear, and bobcat. He had produced a "Poaching 101" video of his exploits.

In court, a biologist for the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries testified that the state had already invested one million dollars to establish the herd in Buchanan County. The Southwest Virginia Elk Foundation had contributed an additional $100,000 to maintain elk habitat.14

Virginia never planned to recoup the state's investment by selling hunting licenses for elk, but after hunting was authorized license fees would offset some of the annual operating costs.

The Kentucky Fish and Wildlife Commission had charged $200-$550 for a less than 600 elk permits in 2019, but hunting and scouting efforts generated four to five times that amount of revenue for local motels and stores.15

Buchanan County was the only jurisdiction in southwestern Virginia to support reintroduction of elk

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The small size of the herd in Virginia, and the limited amount of public land open to hunting in the area where the elk live, will limit the income that the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources could generate from elk hunting fees. Most economic benefits from reintroduction will come from tourists who spend money in Buchanan County on meals, motels, and gasoline while visiting to see the elk, rather than to hunt them.

Reintroducing elk is altering the strip-mined lands and adjacent forests in multiple ways. Their hooves compact the soil, and erosion is greater where they create trails into the forest. Their browsing limits the ability of forests to get re-established on the grassland created by minining companies, the "restored" lands after mountaintop removal of coal.

Elk are the largest animal in Southwestern Virginia. As a keystone species, their effect on the environment is disproportionately large compared to their already-large biomass. Dr. John Cox, a professor at the University of Kentucky, summarized the ecological impacts of elk on strip-mined lands:16

The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries updated its 10-year plan for elk management in 2019. It kept Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise Counties as the designated Elk Management Zone, but made clear that no new reintroductions of elk would occur for the next decade. The existing herd grazed primarily on a 2,600-acre restored strip mine site near Grundy in Buchanan County, and expansion from there would occur only by natural increase.

Away from the reclaimed strip mines, elk are still seen as pests by Virginia farmers. In 2019 the Virginia Farm Bureau Federation successfully blocked a proposal in the 2019 General Assembly to create an elk hunting tag, and the Wise County Board of Supervisors renewed its opposition to any expansion of the elk management zone beyond Buchanan County. One Wise County supervisor described his concerns about elk:17

no additional reintroductions of elk are planned before 2028

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Virginia Elk Management Plan 2019-2028

In 2021, a Tazewell County farmer realized that elk were present on his farm. It was not yet legal to hunt the species in Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise counties; licenses in the Elk Management Zone would not be issued until the fall of 2022. However, a hunter with a state deer license could harvest an elk in Tazewell County.

The farmer used a .50-caliber muzzleloader to legally kill the 700-pound bull elk, reporting it the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources just like a deer. The elk was so heavy that the successful hunter had to revise his plan to hang the carcass from his barn beam; he ended up quartering it in order to get the meat into a cooler.18

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources opened the first elk hunting season in 2022. The first lottery using a randomized computer drawing to grant the right to kill an antlered elk between October 14-20, 2022 resulted in 31,951 applications. That lottery generated $513,000 in fees ($15 for Virginia residents and $20 for nonresidents) for the five available tags.

A sixth tag was auctioned off by the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, and the $100,000 paid for that tag was donated for conservation efforts within the Elk Management Zone - Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise counties. In the first elk hunt, all six tag holders killed an elk in 2022.

The elk were concentrated in Buchanan County, with an estimated 200 there. About 45 were thought to be established in Wise County, with 50 more wandering in the region. The state wildlife biologist responsible for the elk herd reported:19

Virginia's first scheduled elk hunting season was in October, 2022

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Virginia Elk Hunt Lottery

As anticipated, the elk became a tourism draw. Their accclimation to people affected the first hunt; rather than view humans as a threat, the elk just ignored them. As a result, the inaugural licensed elk hunters found it easy to kill a mature trophy bull with minimal effort.

Of the first six hunters, of which only one had previous elk hunting experience, four killed their elk after just a few hours of hunting on the first day of the season. The remaining two hunters were successful on their second day in the field. In contrast, just 60-65% of Virginia deer hunters manage to kill a deer, and on average that requires 10 days of hunting.

A former deer program coordinator with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources questioned the ethics of hunting animals which were not fully "wild" after being tourist attractions for several years:20

the first six licensed elk hunters were all quickly successful in 2023

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Six Hunters Successful in the Inaugural Elk Hunt in the Elk Management Zone of Virginia

Commercial elk-watching bus tours on private land started at Breaks Interstate Park in 2021, and helped lead to a record-setting number of overnight visits. The park manager said in 2022:21

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Elk in Virginia

By 2023, elk had migrated back into Giles County. They had been introduced there in 1917 and 1922, but the last elk killed in Giles County by a hunter was in 1958 - until 2023, when a hunter again killed an elk there.

The elk also expanded their range to include Breaks Interstate Park. Park officials had anticipated their arrival. They prepared a five-acre viewing area by removing invasive species and planting native grasses, hoping to attract the elk away from the fairways of the nearby Willowbrook Golf Course.22

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) anticipated elk becoming a traffic hazard on the 14 miles of Corridor Q between Grundy and the Kentucky state line. The state agency planned to install an elk detection system to warn drivers that a 1,000 pound animal might be grazing on the roadside vegetation. The Virginia Department of Transportation also included identifying high-risk elk crossing locations in a $600,000 grant received in 2023 from the US Department of Transportation's Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program.23

elk reached Breaks Interstate Park in 2023

Source: Virginia State Parks, Breaks Interstate Park (February 10, 2023)

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, < href="https://youtu.be/IjjtfV0CARw">Tracking Virginia Elk with GPS Collars

modern technology allows tracking the movements of elk that were relocated from Kentucky to Virginia

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Elk with Monitoring Collar

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Tracking Virginia Elk with GPS Collars

tourists in Buchanan County may hear male elk bugle during the mating season in September/October

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bull Elk in profile