the Coalfields Expressway was planned to be a four-lane divided highway across the Appalachian Plateau

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), What Is The Coalfields Expressway?

the Coalfields Expressway was planned to be a four-lane divided highway across the Appalachian Plateau

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), What Is The Coalfields Expressway?

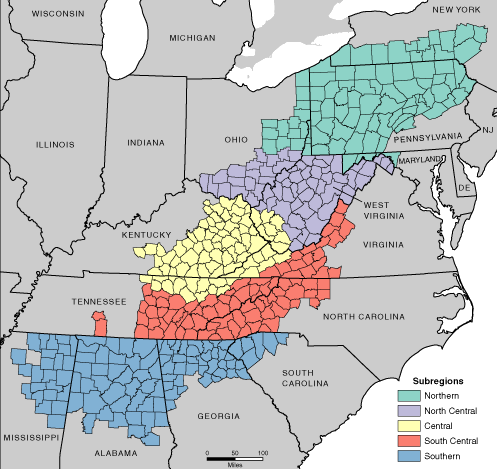

The Appalachian Plateau region of Virginia has been economically distressed ever since Europeans settled the area. High-quality farmland in the area is scarce, and transportation through the mountains is difficult.

The coal and timber industries grew after the Civil War as railroads built a network of lines throughout the region, but wealth generated by those industries went primarily to companies and shareholders outside the region.

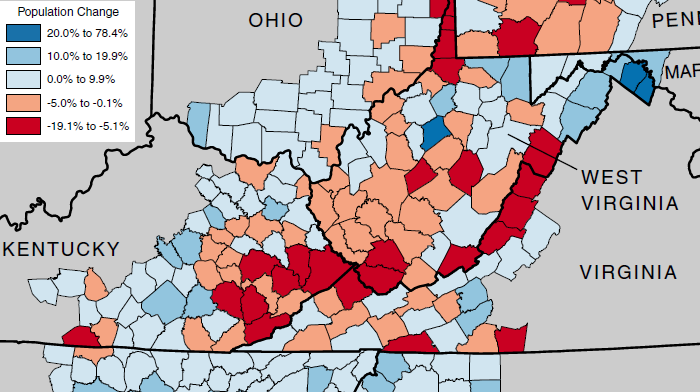

population declined in Buchanan, Dickenson, and many nearby Appalachian counties between 2000-2010, while Virginia's overall population grew by 13% in that decade

Source: Appalachian Regional Commission, Population Change in Appalachia, 2000-2010

After World War I, electricity allowed factories to be located almost anywhere, and automobiles allowed workers to live far from their jobs. Suburbs expanded as new highways were built to link the job centers to residential areas, and retail stores moved from downtowns to shopping centers. After World War II, Federal funding subsidized a massive expansion of highways, including a new system of limited-access interstate highways.

Few new factories or roads were constructed in Wise, Dickenson, or Buchanan counties, however. Routes that involved lower construction costs were chosen for new interstates. The plateau remained a region of two-lane rural roads with steep hills and tight curves limiting drivers to average speeds of around 30 miles/hour. In 2012, Dickenson County had no four-lane highways.1

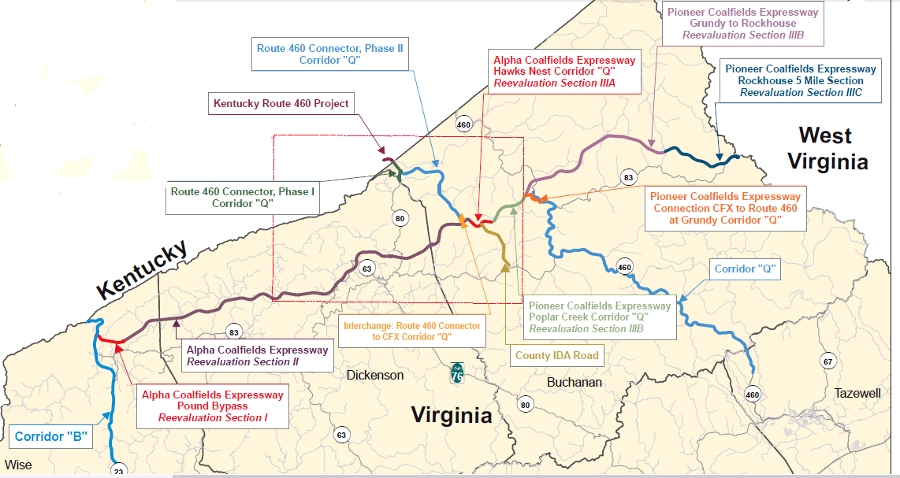

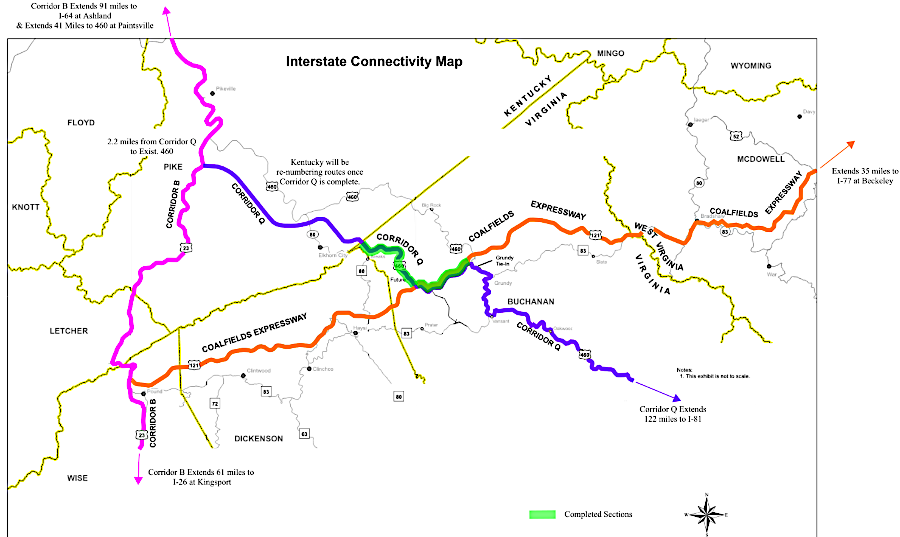

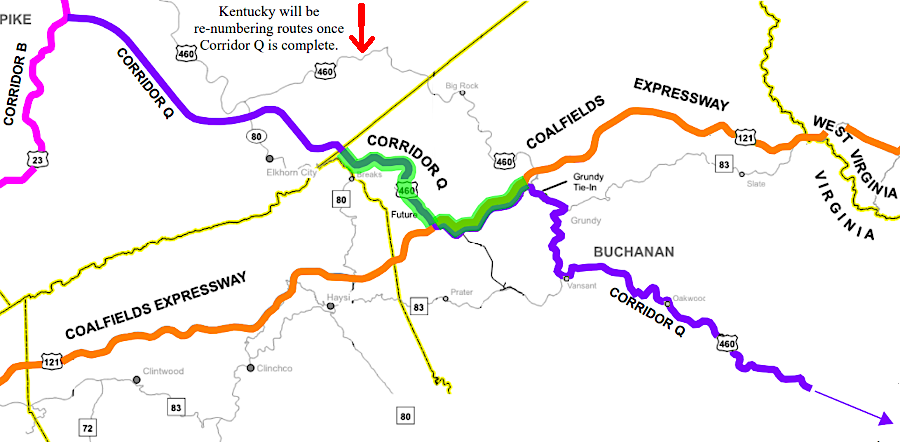

As mines mechanized and demand for coal slackened, Appalachia stayed as an economic backwater and poverty increased. Under President Johnson, the US Congress approved construction of the Appalachian Development Highway System, with a separate funding source from other Federal highways in the affected states. Road improvements have been made in Corridor B (US 23) and Corridor Q (US 460), but sparse connections to Bristol, Roanoke, or other metropolitan areas have limited the potential for local economic growth.

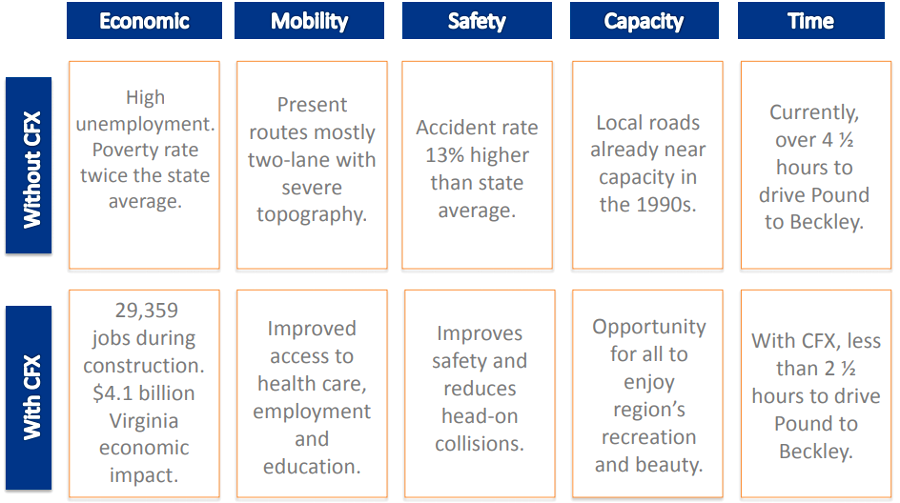

The Coalfields Expressway (CFX) is intended to build a highway allowing average speeds of 55 miles/hour. That is twice the average speed on the alternative route, the two-lane US 83. In the National Highway System, the Coalfields Expressway would be numbered U.S. Route 121.

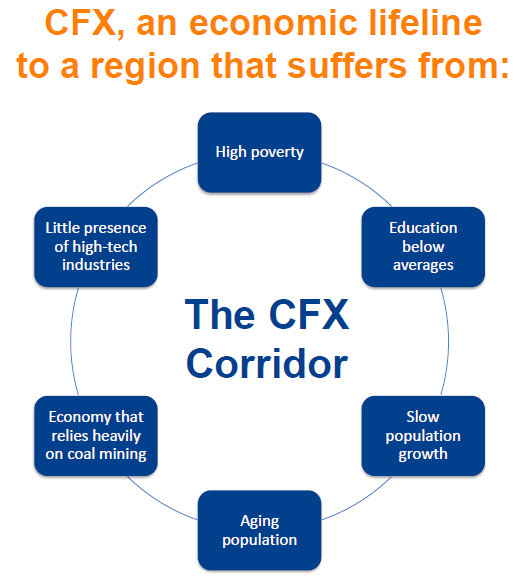

"Purpose and Need" of the Coalfields Expressway (CFX) is to transform the region

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Coalfields Expressway Briefing (January 16, 2013)

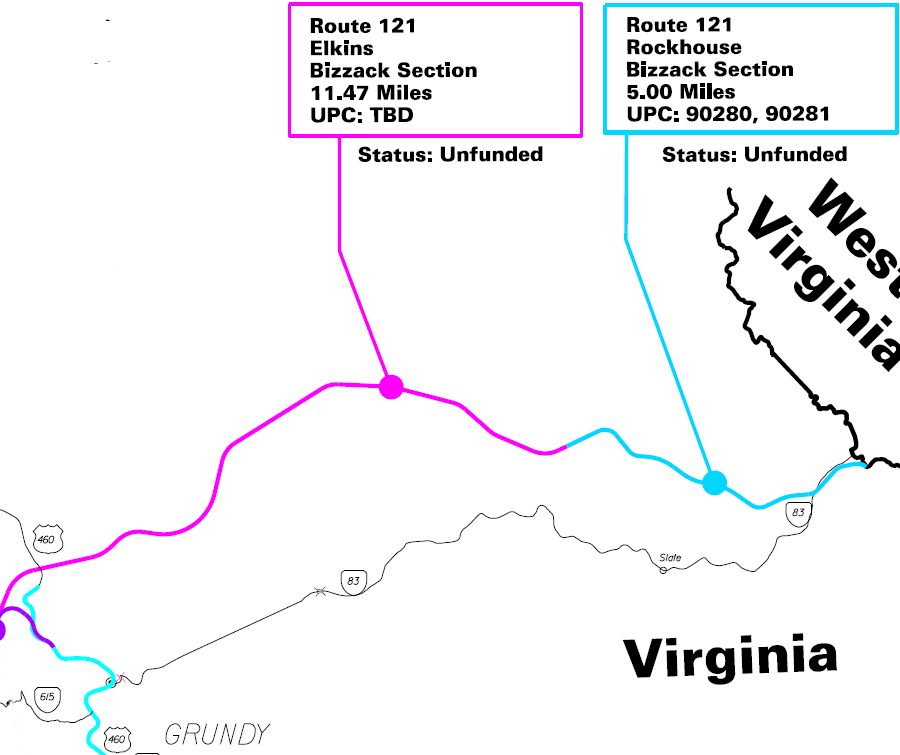

The expressway involves constructing 50 miles of new highway in Virginia, plus 65 more miles in West Virginia. Initial portions could be just two lanes wide, but when completed U.S. Route 121 would be a four-lane divided highway connecting the town of Pound in Wise County to I-64/I-77 at Beckley, West Virginia. The routes of the Coalfieds Expressway and Corridor Q overlap for 17 miles in Buchanan County.

The Coalfields Expressway was not planned as part of the Appalachian Development Highway System, with its letter-based "corridors." Except for a six-mile section of Corridor Q costing $715 million, the Coalfields Expressway had to obtain funding from other sources.

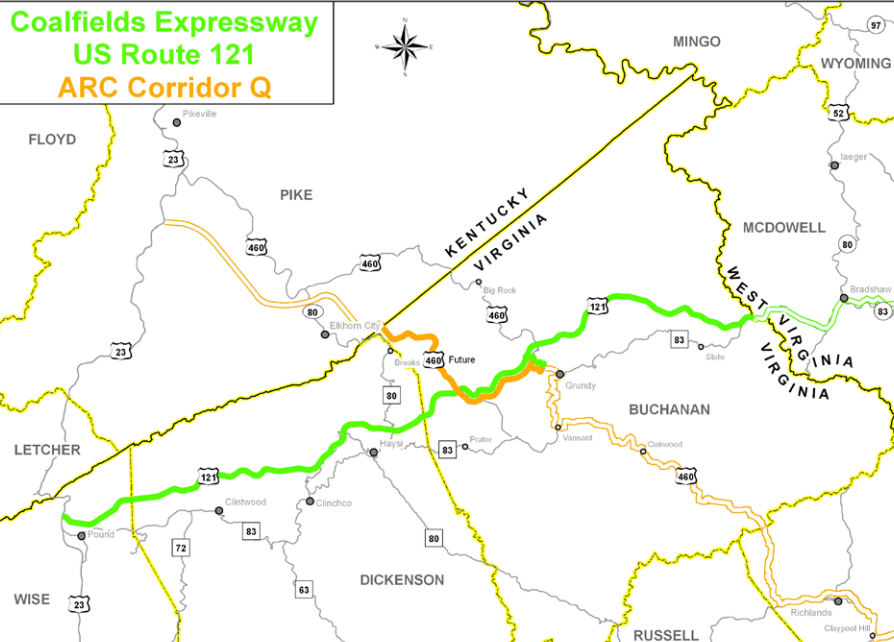

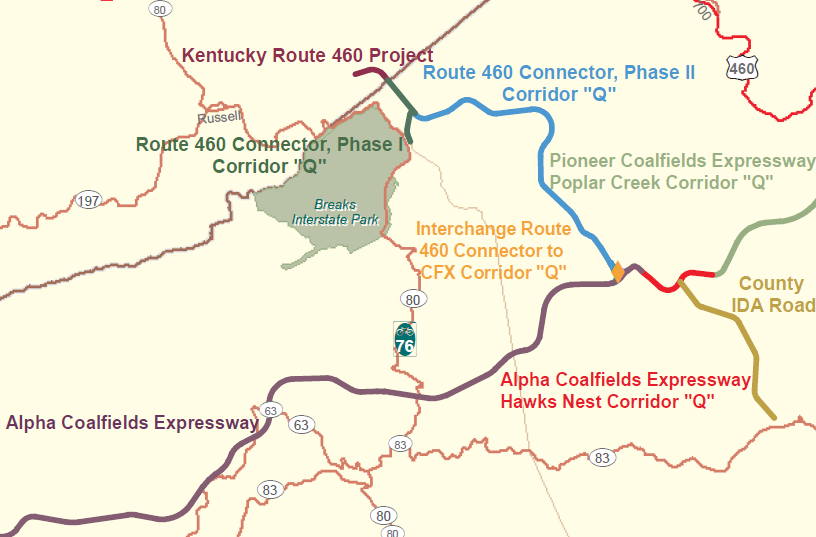

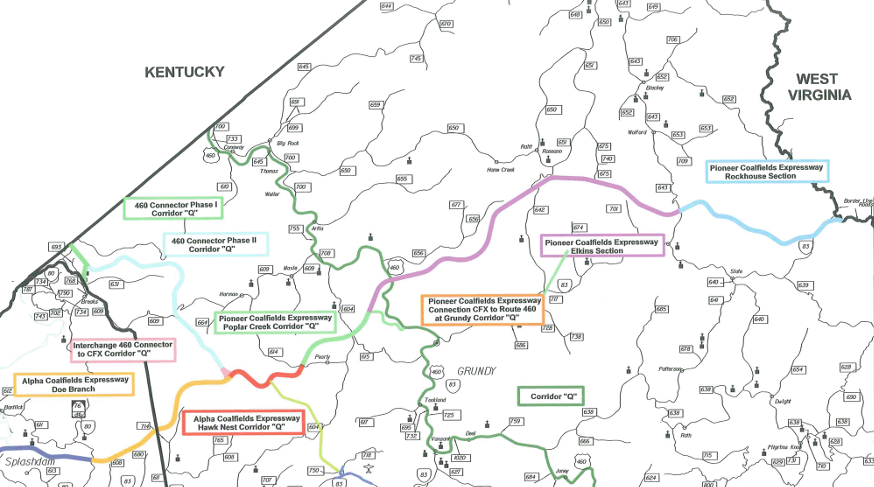

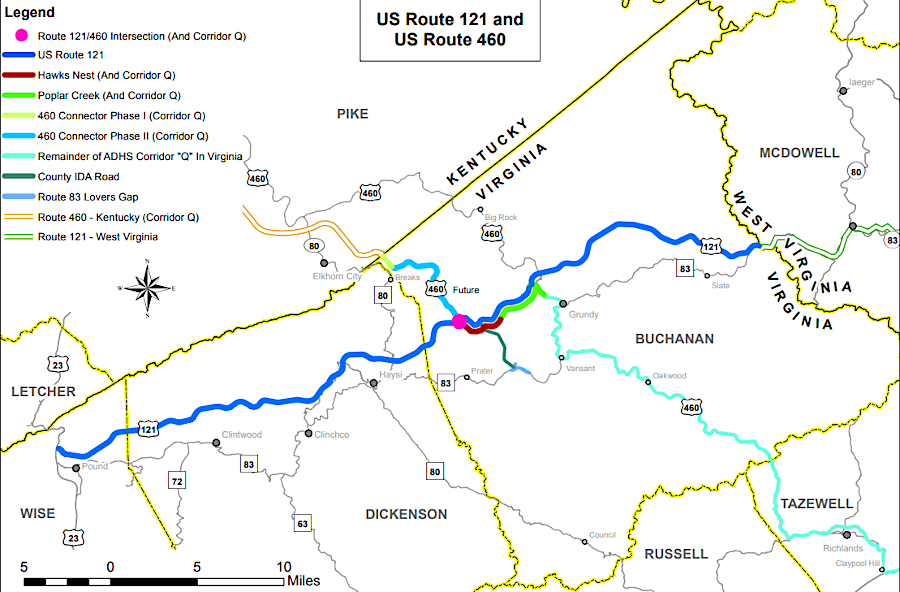

Corridor Q was planned to become a new US 460 between Pikeville, Kentucky and Grundy, Virginia. When the 30 miles of Corridor Q are completed, with 16 miles in Kentucky and 13.8 miles in Virginia, it will shorten the driving distance using the "old" US 460 between Grundy and Pikeville by over 10 miles. The section of Corridor Q in Kentucky was scheduled for completion in 2023, and the Virginia section was scheduled for completion in 2026. Though no part of the Coalfields Expressway crossed into Kentucky, that state joined with West Virginia and Virginia in 2021 to advocate for Coalfields Expressway funding.

Highway 80 between Belcher, Kentucky and Breaks Interstate Park was renumbered from Highway 80 to US 460 in late 2020, when the first section of Corridor Q opened. About six miles of Corridor Q between Hawks Nest and Grundy will numbered as US 480 and also as U.S. Route 121, once the Coalfields Expressway is completed.

Corridor Q, an Appalachian Development Highway System project, will connect segments of the Coalfields Expressway

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Coalfields Expressway: The Road to the Future (Figure 1)

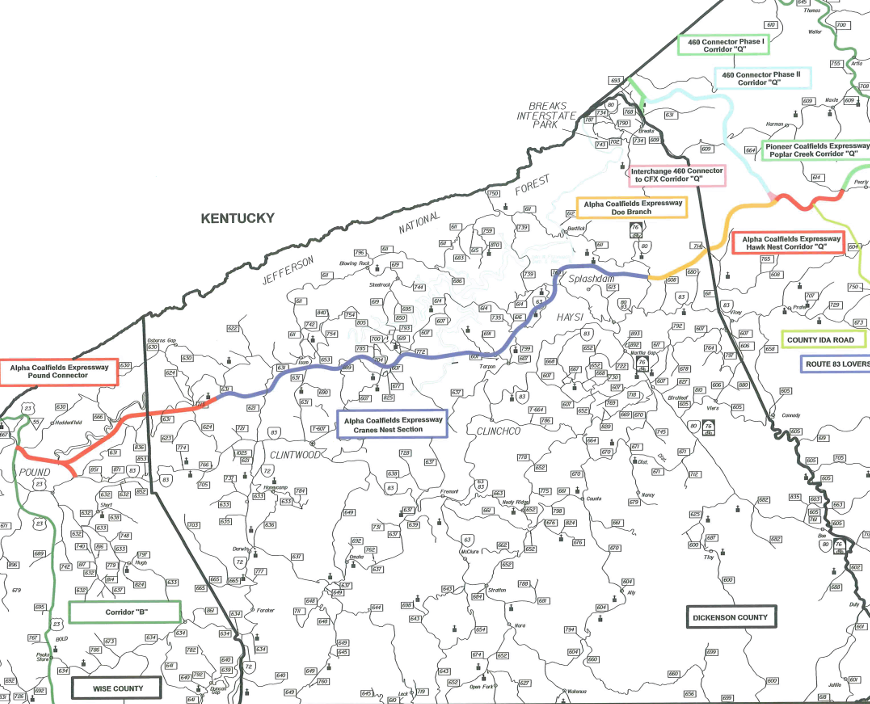

The Coalfields Expressway/US 121 was planned to start at Pound and go northeast from US 23, which is also known as Corridor B in the Appalachian Development Highway System. Interchanges are planned at Pound, Clintwood, Clinchco, Haysi, Breaks, Grundy and Slate.

The expressway will pass through some of the least-populated sections of Wise, Dickenson, and Buchanan counties before crossing into West Virginia. In 2021, there were still no four-line roads in Dickenson County; the only four-lane road in Buchanan County was US 460 from Grundy east to the Tazewell County line.

Because population levels were so low, building a new highway did not guarantee a high increase in traffic. Once West Virginia completed its connection to Interstate 77, the number of cars on the two-lane section of the Coalfields Expressway between Grundy and the state line would increase 100% - but the total traffic was projected to increase from just 7,500 vehicles/day to 15,000 vehicles per day.

By comparison, two-lane Cary Street Road in Richmond between Three Chopt Road and River Road carries 22,000 vehicles per day, and 21,000 vehicles per day use the two-lane section of US 29 through Manassas National Battlefield Park.2

the Coalfields Expressway will be linked to US 460 by the Corridor Q project

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Environmental Assessment - US Route 460 Connector, Phase II (Figure 2: Route 460 Connector, CFX, and Corridor Q)

The benefit/cost ratio of the Coalfields Expressway and Corridor Q are controversial. In contrast to transportation projects in Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads, there is no congestion to be relieved by construction of the Coalfields Expressway. The road is intended to stimulate new traffic. According to the Virginia Department of Transportation:3

As the US Congress debated a massive infrastructure proposal in 2021, political leaders were vocal in their statements that the Coalfield Expressway would not receive funding from processes that relied upon competitive grants. The Smart Scale process used by the Virginia Commonwealth Transportation Board prioritized projects that reduced traffic congestion. Traffic in the Appalachian region was slow, but because of curves rather than rush our commuting patterns. The Coalfield Expressway was designed to increase freight traffic by stimulate new manufacturing facilities in the region, rather than mitigate existing congestion.

The new road also had to compete with proposals to invest in extending broadband to improve internet connectivity. It might be cheaper to stimulate new job opportunities in the region by extending wires for remote workers to move packets of information electronically, rather than building a new road. The executive director of the Virginia Coalfields Economic Development Authority argued for investing in both broadband and in the Coalfield Expressway:4

Virginia's portion of the Appalachian Plateau is isolated from the rest of Virginia, and economically/culturally is more similar to eastern Kentucky

Source: Appalachian Regional Commission, Subregions in Appalachia

The original route of the Coalfields Expressway was along ridgelines already strip-mined for coal. Choosing a relatively flat route minimized construction costs, but after the "dot.com" recession of 2000 there was not enough funding to build the road. A private financing provided through a Public Private Transportation Act deal, arranged with Kellogg Brown & Root Services, was not sufficient.

The "coal synergy" solution appeared in 2005, when VDOT decided to partner with coal companies. In 2007, the Coalfields Expressway was re-routed up to 2-3 miles to cross locations where coal could be profitably extracted as the roadbed was constructed, and where the threat of eminent domain for highway land acquisition would facilitate access to the coal reserves.

As large equipment cut through the hillsides to prepare the "rough bed" of the new highway, coal that was encountered was stockpiled and then sold. The coal was extracted from thin beds that were not normally economic to mine because of excessive overburden. Without the highway project, the coal would have been left unmined.

The construction companies bidding on segments of the Coalfields Expressway calculated the income they could generate by selling the coal, then offered low bids for the construction costs. The Virginia Department of Transportation estimated construction costs to be $1.6 billion in 2001. Within a few years, the estimate climbed to $4.1 billion. By 2006, the Virginia Department of Transportation calculated that traditional construction would cost $5.1 billion.

By offsetting costs through sale of coal, the road could be built for $2.8 billion:5

The route crossed steep hills and deep valleys. One cut through a hillside will be about 400 feet deep, and the deepest fill will be about 600 feet high - the largest cuts and fills on a Virginia highway. One benefit of using the heavy strip-mining construction equipment was that the road bed in the fills could be compacted at lower cost. A member of the Virginia Coalfields Expressway (CFX) Authority Board noted that building the road using traditional construction techniques would be too expensive, and:6

construction of the Coalfields Expressway (US Route 121) included five phases plus Corridor Q

Source: Virginia Coalfields Expressway Authority, CFX Project Map

Even with a 45% savings through the coal synergy construction technique, VDOT planned to spend $2.8 billion to complete a road in southwestern Virginia where there was minimal traffic. The cost-effectiveness of the project remained questionable. According to the economic impact analysis of the Virginia Department of Transportation, the investment of $2.8 billion in public funds will increase long-term tax revenues by only $2.5 million annually.7

Environmental groups expressed opposition, noting that the new route bypassed the economic hubs in the region that were supposed to benefit from additional transportation infrastructure. Transportation activists in metropolitan areas have suggested far more people would benefit if that $2.8 billion was applied to projects that improved the flow of commuter traffic in urban and suburban areas.

The Coalfields Expressway was a taxpayer-funded subsidy to a rural area, while the 2013 transportation bill passed by the General Assembly (HB2313) forced cities/counties in Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads to increase local taxes to fund road projects in those regions. The Coalition for Smarter Growth in Northern Virginia called the Coalfields Expressway one of the "most wasteful, unnecessary projects in the history of Virginia."8

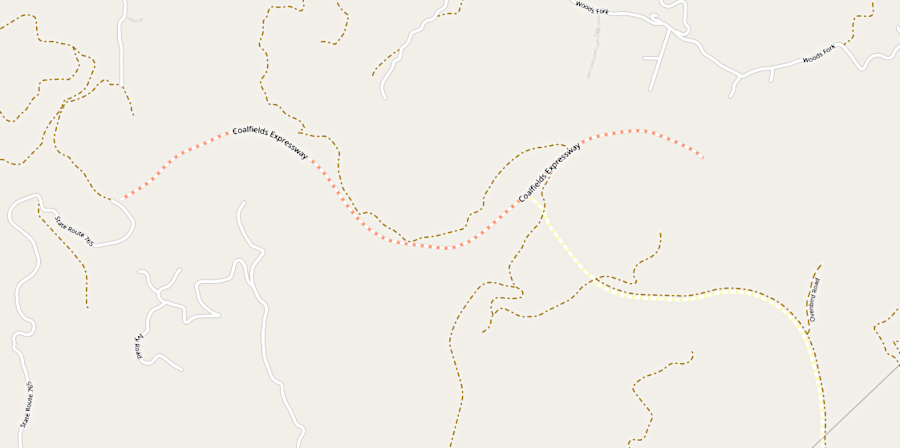

the eastern portion of the Coalfields Expressway in Virginia crosses Buchanan County

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), U.S. Route 121 (Coalfields Expressway)

the western portion of the Coalfields Expressway in Virginia crosses Dickenson County to connect with Pound in Wise County

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), U.S. Route 121 (Coalfields Expressway)

One smart growth advocate, James Bacon, commented as far back as 2005 (when the projected cost was only $3 billion):9

the Coalfields Expressway was designed to link via multiple "corridors" to interstate highways

Source: Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority, map of proposed CFX Interstate Connectivity

In contrast, advocates for the new road noted that wheeled vehicles were essential for moving physical things. The owner of Paul's Fan Company in Grundy, which manufactured ventilation equipment for large buildings, said he kept the family business with 63 employees in Grundy in anticipation of better transportation links to the company's customers. Expansion of manufacturing in the region was constrained by the poor road connections:10

two-lane mountain roads made it difficult to transport components for large industrial equipment

Source: Paul's Fan Company, Mining Fans

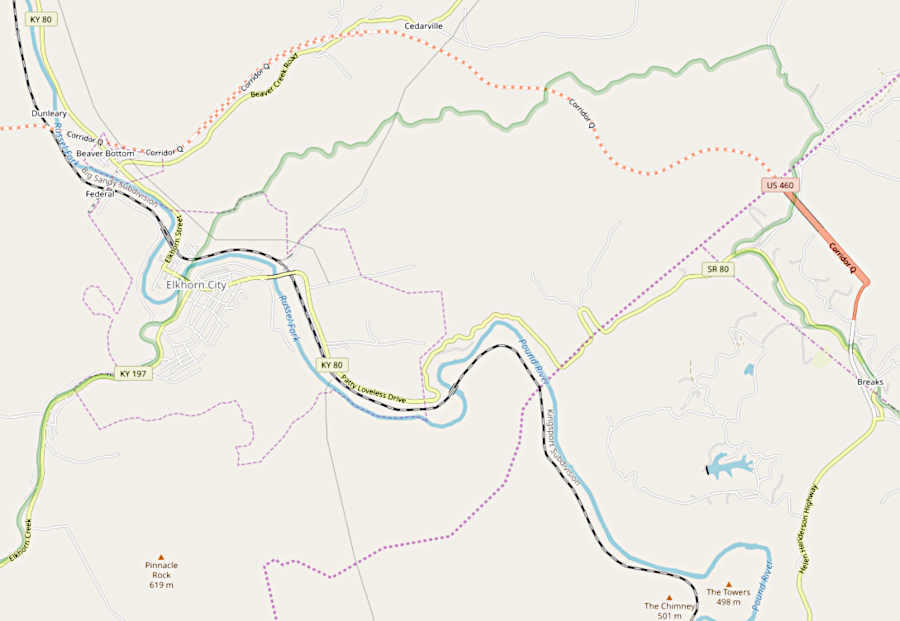

Portions of Corridor Q were completed prior to opening any part of the Coalfields Expressway. The highest bridge in Virginia, 250-foot high across Grassy Creek in Buchanan County, was built for Corridor Q five years before the new road that linked it to existing Highway 80 in Kentucky. The new bridge, which finally opened in 2020, connected initially to just a winding portion of Route 80 in Virginia. The bridge was built with four lanes, but the link in Virginia to US 460 was reduced to just two lanes when Federal funding was reduced.

the highest bridge in Virginia was completed five years before roads on either side connected it to the highway system

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

a portion of Corridor Q linked the highest bridge in Virginia to Highway 80, before Corridor Q was constructed to US 460

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The decision to build an isolated bridge, without funding for the road connections on either side, reflected Virginia's transportation planning approach before 2015. Members of the General Assembly adopted SmartScale then, committing all the funding required to build an approved project. That required limiting the number of approved projects, rather than allocating a small amount of money to many different projects so politicians could claim "something was being done" even without adequate funding to build a fully-functioning road.11

Coalfields Expressway and Corridor Q

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), map of the Route 460/121 corridor

The General Assembly created the Virginia Coalfields Expressway Authority in 2017. That created an official organization for local representatives to oversee and advocate for funding, but members were not appointed by the governor until 2020. The enabling legislation specified that all 12 members had to come from Buchanan, Dickinson, and Wise counties, including the chairs of the Board of Supervisors from those three counties. The Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority provided staff support.

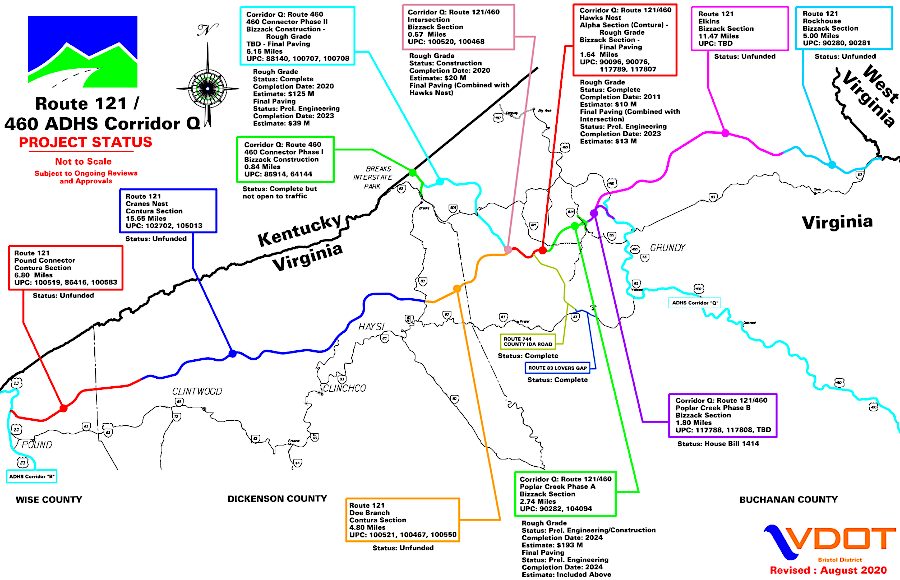

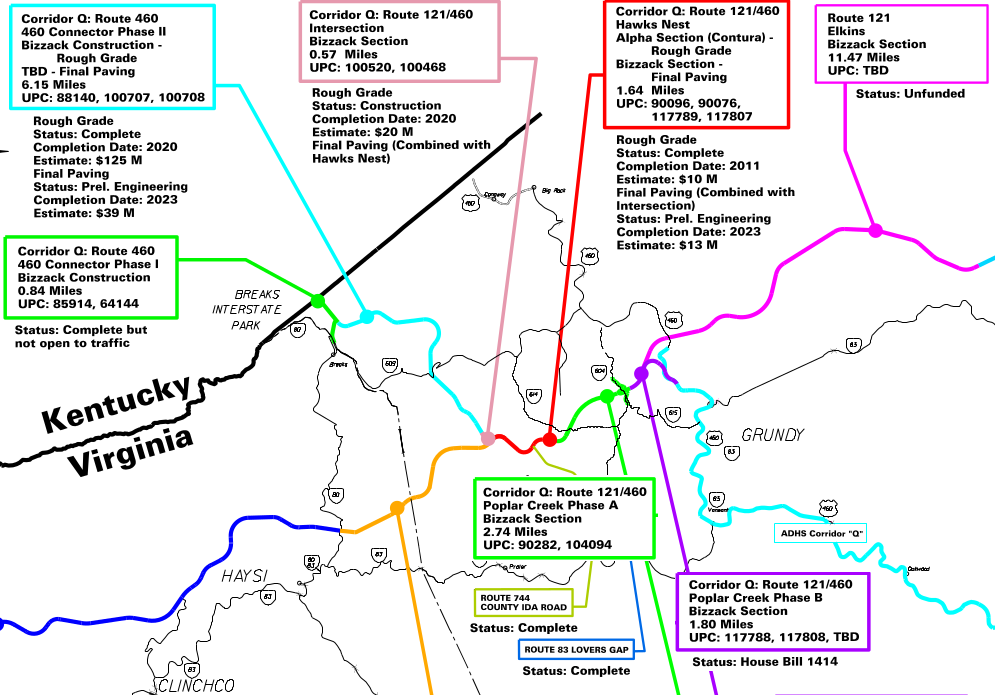

The first "annual report" covered 2017-2020. West Virginia had recently opened its first leg of the Coalfields Expressway, but when the Virginia Coalfields Expressway Authority first met there was only funding for Corridor Q. Including the bridge over Grassy Creek at the Kentucky border, Virginia Department of Transportation planned to build the almost 14 miles of Corridor Q in seven phases:12

six construction phases were planned for Corridor Q

Source: Virginia Coalfields Expressway Authority, CFX Project Map

The coal synergy approach resulted in fragments of highway being partially completed but staying unfinished for years. The Hawks Nest section was excavated to "rough grade" in 2011 and Alpha Natural Resources sold the coal, creating the first section of roadbed for Corridor Q.

The Industrial Development Authority of Buchanan County used the reclaimed land to create the 3,000 acre Southern Gap Business Park. The mining company won an award for its reclamation success, including removing highwalls and restoring the original contour. Restoration included planting hybrid American Chestnut trees, and the site attracted elk which migrated across the Kentucky border. The 7,500-square-foot Southern Gap Visitors Center, highlighting the "Embrace the Wild" tourism slogan for Buchanan County, opened there in 2019.13

coal synergy at the Hawks Nest section facilitated tourism and economic development in Buchanan County even before Corridor Q was completed

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Completing Corridor Q at Hawks Nest had to wait until other fragments of the highway were closer to completion. Paving to finally complete nearly two miles of road through Hawks Nest was not planned until 2023. The 460 Connector Phase II cost $169 million to bring to rough grade by 2019, and the $5 million paving contract ran from 2021-2023.

Nearly $200 million was allocated to complete Poplar Creek Phase A by 2025, but there was only partial funding for the $215 million cost to complete Poplar Creek Phase B. The 2017-2020 annual report highlighted the funding challenge for constructing the rest of the Coalfields Expressway in Virginia:14

in 2021, "Status: Unfunded" applied to all segments of the Coalfields Expressway outside of Corridor Q

Source: Virginia Coalfields Expressway Authority, CFX Project Map

In the last week of his term in January 2022, Governor Northam announced that Federal funding had been obtained to complete construction of Poplar Creek Phase B of Corridor Q. The two mile, two-lane section of Phase B was the final connection between State Route 604 (Poplar Creek Road) and U.S. 460/121.

The governor's approach meant that funding for Phase B did not need to compete for state funding in the Smart Scale decision process used by the Commonwealth Transportation Board. The timing of the announcement allowed the Democratic governor to claim credit for making funding arrangements during his administration. Had the announcement been delayed another week, the new Republican governor might have received credit.

In 2023, 8.7 miles of Corridor Q were opened between Breaks and Southern Gap. The two remaining pieces required before "old" US 460 could be replaced by the Corridor Q route were Poplar Creek Phase A (2.74 miles) and Phase B (2.07 miles). Phase A was scheduled to be completed in 2025, and Phase B in 2027.15

the US 460 route through Southwest Virginia/Kentucky was to be switched to the Corridor Q route, once construction was completed in 2027

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Route 121/Corridor Q: Interstate Connectivity Map

Poplar Creek Phase B of Corridor Q, connecting State Route 604 to US 460 near Grundy, crossed difficult terrain

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Like Corridor Q, the Virginia Department of Transportation also planned to build the rest of the Coalfields Expressway in distinct phases. The Virginia Coalfields Expressway Authority identified the first priority to be construction of the 6.4-mile Pound Connector, improving access from US 23 to the Red Onion Industrial site in nearby Dickenson County.16

The FY2023 Federal budget included $7 million for a smaller portion of Corridor Q. The additional funding meant that 2.2 miles next to the Southern Gap Industrial Park in Buchanan County would be constructed as a four-lane rather than a two-lane highway. The US Congress finally approved that funding in March, 2024. Had the extra funding been delayed, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) would have paved just a few truck climbing lanes rather than the entire stretch as a four-lane highway.17

building 2.2 miles of Corridor Q as a four-lane highway to access the Southern Gap Industrial Park was funded in part by the FY2023 Federal budget

Source: Virginia Coalfields Economic Development Authority, Southern Gap Business Park - Buchanan County Virginia

One out-of-the-box proposal for getting funding for the Coalfields Expressway was to convert it into a technology demonstration project. If the Coalfields Expressway was designed to become a linear solar generating facility, the project might be able to gain funding from research and development sources. The editor of Cardinal News wrote:18

In 2024, the Virginia Department of Transportation installed the first "Coalfields Expressway" signs on completed segments of the highway in Buchanan County.19

Poplar Creek Phase A, between Southern Gap Road and Poplar Creek Road, opened in October 2025. After adding the additional three miles, 12 miles of the planned 50 miles of the Coalfields Expressway had been completed. Completing the other 75% of the road in Virginia was projected to cost $4 billion. In West Virginia, 14 miles of the projected 60 miles were iopen for traffic by 2025.

Poplar Creek Phase B, another two miles connecting to downtown Grundy, was scheduled for completion in 2027. That segment included the second-tallest bridge in Virginia. An additional five miles in West Virginia from from Welch to West Virginia Route 16 was under construction.

The executive director of the Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority emphasized how regional officials viewed the significance of completing the Coalfields Expressway:20

In 2026 the Federal government provided $3 million to pave widen the 4-mile stretch from Virginia 80 at Breaks Interstate Park to Virginia 609 at Bull's Gap. The $3 million would be added to $17.5 million already obtained, plus additional state funding, to eliminate the last two-lane section between Pikeville and Grundy.21

Virginia built Corridor Q in isolated segments, starting with areas where coal could be mined

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Coalfields Expressway logo

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Coalfields Expressway Briefing (January 16, 2013)

the Appalachian Plateau in Virginia lacks interstate highways

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), What Is The Coalfields Expressway?