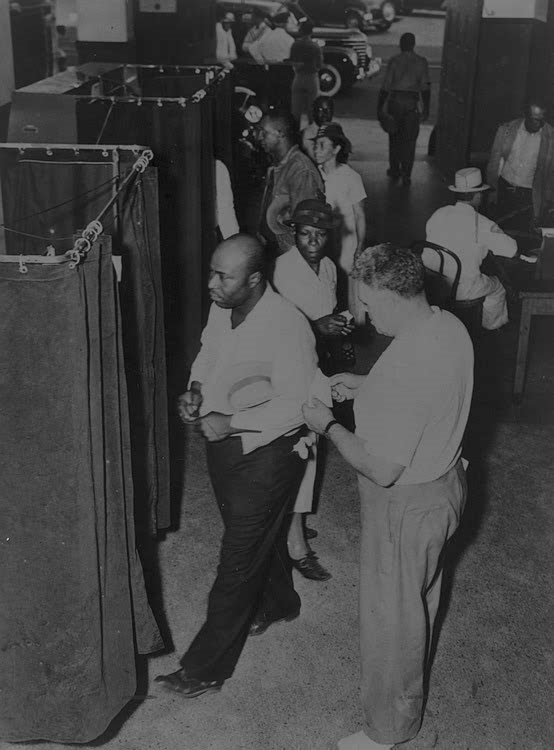

voting after repeal of the poll tax

Source: Library of Congress, The Poll Tax: Twenty-Fourth Amendment Ratified

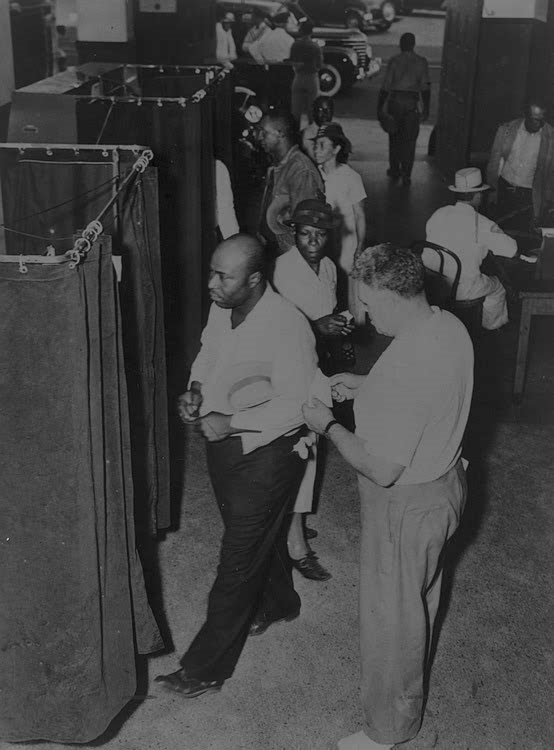

voting after repeal of the poll tax

Source: Library of Congress, The Poll Tax: Twenty-Fourth Amendment Ratified

Virginia prided itself on "honest government" throughout the Byrd Organization days, but it was far from representative. Conservative white Democrats successfully suppressed the black vote, evading the intent of the 15th Amendment with the help of US Supreme Court decisions that allowed racial discrimination in practive so long as the laws themselves appeared to be race-neutral in their lamguage.

V.O Keys described Virginia after World War II as a "museum of democracy." The state had all the trappings of representative government, complete with elections every year, but the electoral process blocked dynamic change that might reflect the will of the people rather than the desires of the Byrd Organization.1

The basic structure of Virginia government before the 1960's was not fair to minorities, women, urban residents, or Republicans. The electoral system was designed to use power to disenfranchise key groups and to concentrate power in just the hands of just a few white men, but personal graft by state officials was not routine.

Members of the Byrd Organization sought to concentrate control more than to accumulate unearned personal wealth. Harry Byrd prioritized effciency in government, and corruption would have been wasteful. Kickbacks on government contracts were unusual, in contrast to the Democratic machines in Chicago, New York, Boston, etc.

Restriction of suffrage was traditional. Virginia started electing members to a General Assembly in 1619, but the right to vote was limited for most of the colonial era to men who owned a certain amount of property. Free black men and those formerly enslaved were enfranchised during Reconstruction, but after the Readjusters were defeated in 1883 most were blocked from exercising an independent right to vote. No women could vote until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920.2

There was vigorous two-party competition in Virginia during the 1830's and 1840's as the Whigs contested with the Democrats, and after the Civil War as the Readjusters and Conservatives contested for power. In 1883, a race riot in Danville was used effectively by the conservatives, organized as the Democratic Party, to take control of the state.

Virginia became part of the Solid South. Winning the Democratic primary for local or state offices was tantamount to winning the election, except in the Fighting Ninth congressional district of Southwest Virginia where Republicans had consistently challenged Democrats. No Republican was elected to a statewide office in Virginia until 1969.

Presidential elections were different, starting in 1928. Herbert Hoover won Virginia's electoral votes after the Democrats nominated Al Smith, a Catholic from New York who supported repeal of Prohibition. Strting with Eisenhower's victory in 1952, Virginians typically supported the more-conservative Republican candidates for president every four years while voting consistently in other years for more-conservative Democrats at the state and local level.3

Virginia politics and government remained largely in the hands of a few white men allied with Harry F. Byrd until the 1960's. Many white Virginians had accepted both segregation and limited voting access for decades, while people of color struggled to use the election process to get government policies and funding to address their concerns. After the 1902 state constitution was adopted, both Republicans and Democrats chose to be "lily white" political parties and excluded blacks from primaries and conventions.

Fighting overseas in World War II to defeat dictatorships altered historical perspectives, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) won lawsuits that undercut the legal structure of Jim Crow segregation. Veterans who settled in the urban areas had an increased sensitivity and desire for a full democratic process in Virginia, and a greater willingness to allow minority groups to exercse political rights.

By the 1950's the Byrd Organization was viewed as reactionary conservative. Harry F. Byrd's "pay-as-you-go" philosophy prevented state and local governments from building schools, roads, and other public infrastructure needed as the population boomed after World War II. Byrd's concept of white supremacy was no longer endorsed in court decisions. The Massive Resistance effort, to block school desegregation after the Supreme Court's Brown vs. Board of Education decision in 1954, was the last attempt of the Byrd Organization to retain power.

Byrd's political power was based on the ability of the appointed and elected officials to restrict the number of voters, and ensure those few voters were supporters of the Byrd Organization (or "machine"). A landslide election would have 7% of the potential electorate voting for candidates supported by Byrd, and 4% voting for the opposition. Less than 15% of theoretically-possible voters actually participated in the process in the mid-1900's.

Byrd's political power was based on white voters in rural areas. Disfranchisement tools and then the poll tax included in the 1902 constitution effectively eliminated the power of votes by blacks.

Officials, especially in the rural counties, ensured that the poll tax was paid for three years in advance of an election for known supporters. Those same officals erecting numerous roadblocks to registration and voting by opponents. Election district boundaries were rawn to ensure the General Assembly was dominated by representatives from rural areas, and the cities received relatively little state support.4

Byrd's support for state-financed education was thin even before racial desegregation was mandated "at all deliberate speed" by the Supreme Court. Like most men of his age, Harry F. Byrd never attended college and did not seek to increase the number of people who could.

Raising taxes for schools and other social welfare programs would benefit the urban centers where people were concentrated - not his support base of farmers. They desired a poorly-educated workforce with few options for finding jobs except as low-paid farm workers.

The Byrd Road Law of 1932 showed clearly how the excessive representation of rural areas in the General Assembly steered government funding away from urban areas. During the Great Depression, the state offered to assume responsibility for maintaining secondary roads in all the counties - but not in the cities. City residents ended up paying state taxes to build and maintain roads in the counties, plus city taxes to support their own local roads:5

Rural areas were over-represented in the General Assembly while urban areas were under-represented. Southside Virginia, particularly counties where blacks were a high percentage of the population, remained the stronghold of the white supremacist Byrd Organization which disfranchised black voters. State and Federal funding for roads and tobacco price supports were welcomed in rural areas, but government interference in traditional cultural patterns was not acceptable. The region had a high percentage of blacks who provided a pool of low-cost farm labor, and whites saw no benefit in changing a social and economic system that had evolved after the Civil War.

Governor Harry F. Byrd

Source: Library of Congress, Byrd, Harry F. Governor

Particularly during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, blacks in other states began switching their allgiance to the Democratic Party and its relatively liberal policies. In Virginia and other southern states, however, conservative white supremacists continued to control the Democratic Party.

By the 1960's, the state of Virginia was schizophrenic in its voting. At the local and state level, the Byrd Organization kept the Democratic Party firm in its conservative outlook and few Republicans were elected. In presidential elections, Virginia voted Republican in support of the conservative national party. In the 60 years between 1948-2008, Virginia always supported the Republican candidate for President, with the exception of the Goldwater-Johnson race in 1964.

Senator Byrd maintained a "golden silence" when asked about his support for national Democratic candidates for President, while granting the "nod" to indicate his personal support for state candidates. By the end of 1999, Virginia was the last state to prohibit designation of a candidate's political party on the ballot. This facilitated voting for conservative Republicans at the national level, while maintaining the conservative Democratic control at the local and state levels.

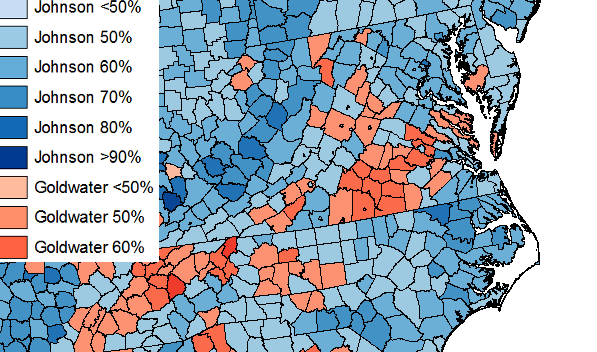

The most rabid support for "massive resistance" to court-ordered desegregation of schools was in the counties where black enslaved people had outnumbered whites before 1865. Election results for the counties that voted for Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election shows how Virginia's conservative voters were concentrated in Southside, while Northern Virginia voters endorsed the more-liberal Lyndon Johnson. One analyst noted:6

Southside counties supported Barry Goldwater in 1964, even though he was a Republican

Source: Wikipedia, United States presidential election, 1964

Into the 1960's, the Republican minority in the General Assembly was irrelevant in the decision process. The Speaker of the House of Delegates assigned Republican legislators to phantom committees which never met. Key decisions, such as the crafting of the biennial budget, were made by subcommittees and committees that met in secret without any Republican involvement. Final bill language was released just before the House of Delegates and State Senate voted, giving no time for analysis or debate.7

Only after the Republicans assumed control of the General Assembly in 2000 was this restriction on party identification seriously examined. By that time, the realignment of the state political parties to match the national ideology had been completed - and the assumption was that listing candidates by party would enhance the election of conservative Republican politicians.8

As the Federal government expanded its role in the Great Depression, World War II, and Cold War, new residents moved into Northern Virginia. They brought with them different attitudes, with greater support for public education and less support for state-sponsored segregation of the races. Many of those who migrated into Virginia from northern states had a different perspective on the heritage of Lincoln and the Republican Party, and lacked the tradition of voting for just Democratic candidates.

In 1960, the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, and a majority of the General Assembly members took an official "field trip" to explore how Northern Virginia was evolving. Jim Latimer, reporting for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, commented that the growing number of voters included many Federal employees who were not native to Virginia, and were:9

The redistricting of the electoral districts for the General Assembly, forced by the Supreme Court, led to greater influence of urban areas, especially Northern Virginia and Tidewater as population swelled in those regions. Harry Byrd retired as U.S. Senator in 1965 before his term concluded, due to ill health. His son, Harry Byrd Jr., was appointed to replace him.

The 24th Amendment to the US Constitution, ratified in 1964, ended the use of the poll tax to limit who could vote in Federal elections. That same year, the US Supreme Court ruled in Reynolds v. Sims that electoral districts had to be redrawn to follow the "one man-one vote" rule. The revision of boundaries gave urban residents in Virginia more influence in the General Assembly, and reduced the dominance of the rural residents. In 1966, the US Supreme Court ruled in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections that Virginia's poll tax was unconstitutional for state elections.

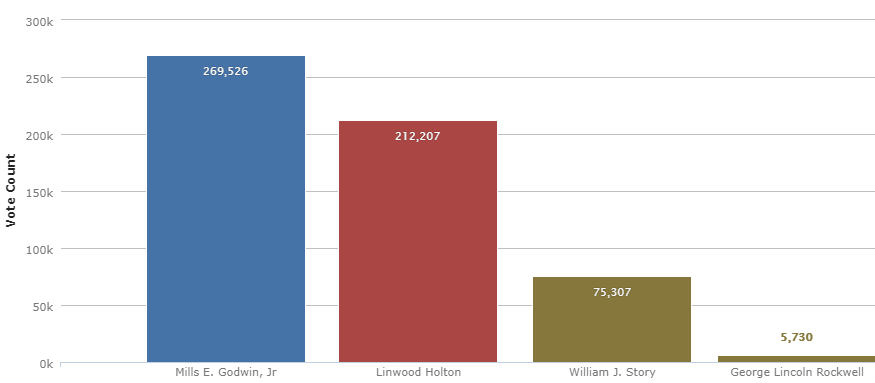

The court rulings and the Civil Rights movement led to an expansion of the electorate, which led to the collapse of the Byrd Machine in the 1960's. In the 1965 campaign for governor the Democratic candidate, Mills Godwin, received only 48% of the total vote. It was sufficient to win, since three other candidates split the other 52%, but it was significant that the Democratic candidate did not win a majority of the total vote. The chair of the Republican Caucus announced proudly in 1966:10

the Democratic candidate for governor received only 48% of the vote in 1965

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, 1965 Governor General Election

Recognizing that the Democratic Party needed to adapt to changed circumstances, Governor Godwin abandoned "pay as you go" budgeting. He endorsed selling bonds and putting the state into debt, in order to finance the construction of community colleges.

In 1969, the Virginia Democratic Party nominated conservative William C. Battle for governor in a bitter primary. More-liberal candidate Henry C. Howell chose to "free his suporters" to vote as they chose, rather than encourage them to supoort Battle. As a result, Republican lawyer Linwood Holton was elected governor. That election reflected the decline of the modern gentry in Virginia; the expanded electorate wanted expanded government services. Voters were willing to raise taxes to fund education and transportation in particular.

Senator Harry Byrd Jr., who had been appointed to the office to fill out his father's term when he resigned in 1965, had narrowly won the Democratic Party nomination in 1966. In 1970, he feared he could not win it again, but was unwilling to be a Republican in a "Solid South" state where that party was still associated with Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. He chose to run as an independent, and Harry Byrd Jr. won election with 54% of the vote.

His victory revealed that the majority of voters were still conservative; Harry Byrd Jr. defeated a liberal Democrat and a Republican who was not viewed as a conservative. His victory also revealed that the political allegiance on conservatives to the Democratic Party was crumbling, but Republicans were still associated with the "party of Lincoln" and support for blacks.11

In 1973, political conservatives shifted their allegiances and abandoned the Democratic Party. Business-oriented conservatives established control over the Virginia Republican Party, repudiating Republican Governor Holton in the process.

The defection of the conservatives allowed the Virginia Democratic Party to align itself finally with the social activism of the national Democratic Party. At the same time, the Virginka Republican Party aligned itself with the conservative agenda of its national party under President Richard Nixon. Larry Sabato, a keen observer of the political system in Virginia, titled his book on that election Aftermath of "Armageddon": An Analysis of the 1973 Virginia Gubernatorial Election.

Virginia elected its second Republican governor in 1973, but this time the Republican candidate was the choice of conservatives. Henry Howell, a liberal Democrat, chose to run as an independent in hopes of retaining support from traditional Democrats. The Democrats did not nominate a candidate for governor, to avoid splitting the vote for Howell.

Mills Godwin, who had served as a Democratic Governor in 1966-70, changed parties and ran as a Republican in 1973. He had sought to run as an Independent, but was forced to identify as a Rpublican in order to receive the nomination. At the convention, he started his acceptance speach with "As one of you..." and received a standing ovation.

As a result of party realignment during the "Armageddon" election in 1973, Godwin's change in parties did not require a change in his conservative principles. His election as a Republican revealed that Virginia's voters were more interested in conservative government than in loyalty to the Democratic party.

as a Democratic governor in 1966-70, Mills Godwin was a progressive for that time - but in 1973, he was elected again as a conservative Republican

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), Creation of VCU

In the 1980's Rev. Pat Robertson and Rev. Jerry Falwell mobilized conservative Christians and led their religious followers into the Republican Party, after being rejected by Virginia Democrats. Half the governors in the last third of the 20th Century were Republicans. However, thanks in part to the institutional barriers established by the Byrd Organization, Republican control of the legislative branch and local county offices came much later.

In the November, 1999 elections, the Republicans finally took complete control of the General Assembly. After some astute maneuvering by Governor Jim Gilmore, Republicans gained majorities in both the House of Delegates and the State Senate. Governor Gilmore celebrated by using Martin Luther King's "free at last" phrase, reflecting the frustrations of a minority party finally achieving political control.12

Tension emerged within the modern Virginia Republican Party between those who focus on the role of government in protecting business opportunities and those who view government as an engine for social change. Party allegiance was not tight. Rather than focus exclusively on getting out the vote from members of just one party, candidates appealed for support from both Democratic and Republican voters.

During the 2001 election for Governor, a new "Virginians for.." movement was created, in this case "Virginians for Warner," the Democratic candidate for governor. During the heyday of the Byrd Organization, a "Virginians for.." movement had been the traditional mechanism for Virginia Democrats to support national candidates running on the Republican ticket. In 2001, however, it was former Republicans who created a party-neutral Virginians for Warner mechanism. It offered a way to support a Democrat perceived as more focused on expanding business opportunities, rather than advocating for a conservative social agenda.

Pendulums swing, and parties gain/lose power. Democratic candidates (Mark Warner and Tim Kaine) won the 2001 and 2005 elections for governor. The Democrats also won control of the 40-member State Senate in 2007, and a Democrat (Jim Webb) upset the Republican incumbent (George Allen) in the race for the US Senate. The final stage in moving away from being a museum of democracy occurred in 2008, when Virginia became a battleground state in the presidential election and voted for Barack Obama over John McCain.

In subsequent elections in 2009 and 2010, Republicans were victorious in state elections. Virginia became a "purple" rather than a "red" or "blue" state, with voters willing to switch between parties.

One legacy of the one-party system in Virginia was finally broken in 2017. For the first time, both the Republican and Democratic parties had primaries for governor. Two factors were involved:13

- there enough strong candidates with enough support to finance a contest

- both parties chose to use primaries to nominate candidates rather than conventions, where party activists dominate the process and "average" voters have less influence

The Republican Party lost public support after 2010. It did not help that Republican Gov. Robert McDonnell was indicted in 2014 and convicted of corruption right after his term ended, though the US Supreme Court ultimately overturned the conviction by ruling the law was too vague.

in the 2019 election, Democrats achieved a "trifecta." They won the governorship and control of both houses in the General Assembly. That enabled them to pass a progressive set of laws, undoing many of the policies adopted by the Republican majority in the legislature for the last two decades.

By 2020, Virginia was considered a "blue" state that would reliably support Democratic candidates in statewide elections. Elections were contested and Republicans had an opportunity to recapture one of both of the houses in the General Assembly, but at the state level there was a presumption that a swing of the pendulum to create a Republican trifecta was not possible.

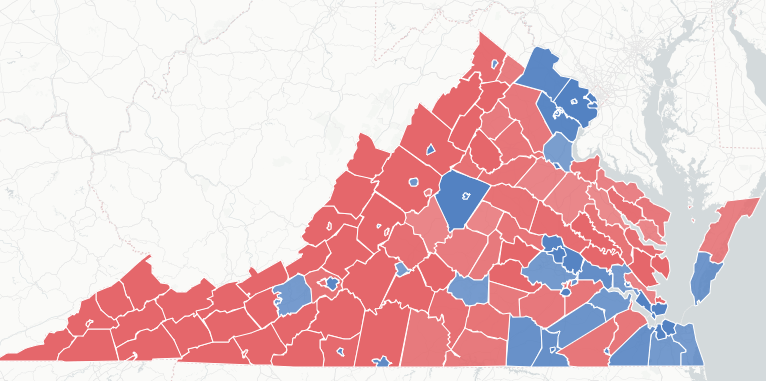

Democratic candidates consistently ran up large margins in the cities, and urban and suburban voters outnumbered rural voters. Maps that showed the vote by jurisdiction were primarily red and reflected the dominance of the Republican party in rural areas, but elections are decided by voters rather than by acres.

most voters supported the Democratic candidate for president in 2020, but most jurisdictions were "red" rather than "blue"

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Localities: Number of Registered Voters

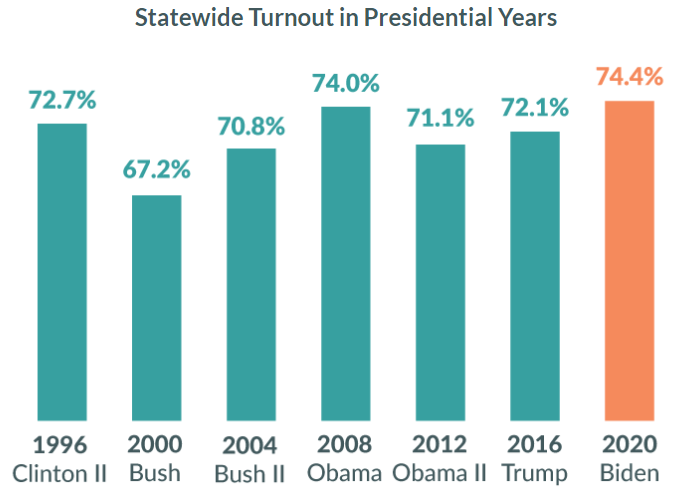

The 2020 election set a new record for voter participation. The General Assembly relaxed restrictions on early voting and voter identification mandates. During the COVID-19 pandemic, drop boxes were provided for direct delivery of early votes in addition to reliance on delivery via the Post Office. In the presidential race, 74% of eligible voters cast a ballot in 2020.14

in the 2020 presidential election, turnout exceeded 74% and set a record

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Partisan Change from 2016