Rutile Lane is a reminder of the titanium ore in Nelson County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Rutile Lane is a reminder of the titanium ore in Nelson County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Vanadium Corporation of America began mining titanium at Piney River in Nelson County in 1931. It was processed into titanium dioxide to color ceramics, as a pigment in paint, and as a steel alloy. Between 1957-1968, M and T Chemicals mined and processed primarily rutile (TiO2) in Hanover County for ceramics, including floor tiles. In both places, open pits exposed saprolite (weathered bedrock) derived from titanium-rich pegmatite dikes as well as the intrusive dikes.

At Piney River, the top 100' of saprolite were excavated. The primary mineral in the ore was ilmenite (FeTiO3). Along the Piney and Tye rivers, titanium was also present as rutile (TiO2). Rutile Lane is still located near Roseland in Nelson County.

The ore was crushed, concentrated, and processed at a plant four miles from the mine to create titanium-dioxide pigment. The material was shipped via the Blue Ridge Railway, constructed originally in 1915 to transport chestnut trees to mills. The disappearance of the chestnut and the Great Depression could have caused the railroad to close, but the titanium mining/processing and nearby quarries kept the railroad in business.

Riverton Lime & Stone Company opened a quarry in 1939 that extracted aplite, another intrusive igneous rock rich in feldspars and quartz. Carolina Minerals opened a second aplite quarry in 1941.

The fine-grained aplite was found near coarse-grained pegmatite dikes. Both formed as magma derived from continental crust that crystallized into granite that metamorphosed into gneiss in the Blue Ridge. The aplite is rich is calcium phosphate, making it particularly useful for agricultural fertilizer. Virginia's state rock is Nelsonite, a titanium ore formed primarily from the minerals ilmenite and apatite.1

Nelsonite, designated the official state rock of Virginia in 2016, is composed primarily of ilmenite (FeTiO3) and apatite (Ca3(F,Cl)(PO4)3). The titanium and calcium phosphate minerals separated from the magma as it cooled and crystallized into nelsonite rock a billion years ago.2

In 1944, American Cyanamid Company bought the Piney River operation, expanded operations, and became a major employer in the area.

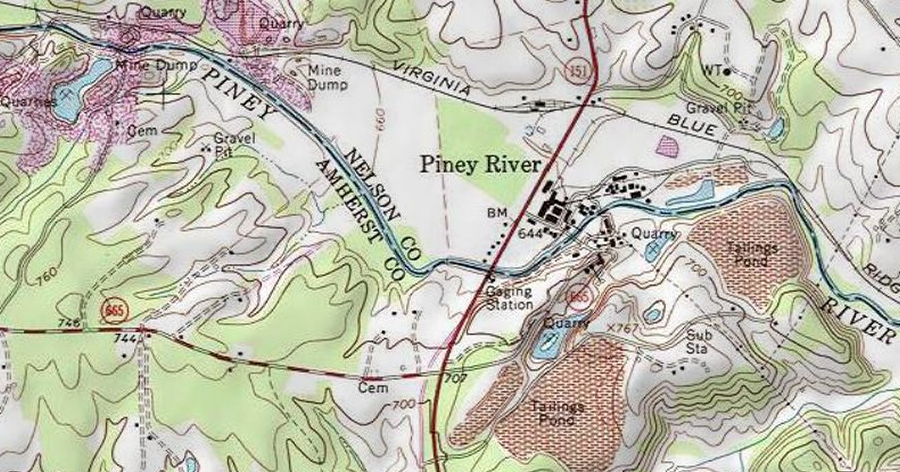

American Cyanamid Company mined and processed titanium ore on the Piney River from 1931-1971

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Piney River 1:24,000 quadrangle map (1963)

The process for converting the titanium ore into the final product involved sulfuric acid, which the company dumped into the Piney River. In 1946, the Commission of Game Inland Fisheries (now the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries) issued a citation to American Cyanamid Company for "casting noxious substances into Piney river." A second citation was issued in 1947.

A lawsuit contesting the two $25 fines followed. The final appeal reached the Virginia Supreme Court in 1948, and it noted:3

The Virginia Supreme Court ruled the first citation was valid, but the second in 1947 had occurred after the State Water Control Board had issued a water pollution permit to the company. The General Assembly created the State Water Control Board in 1946, two years before the US Congress passed the Federal Water Pollution Control Act to address unrestricted pollution discharges at the Federal level. That law evolved into the 1977 Clean Water Act enforced by the Environmental Protection Agency, but in 1946 the regulation of water pollution was in its infancy.

The State Water Control Board permit authorized American Cyanamid Company to discharge sulfuric acid into the Piney River. The permit was issued after the company claimed it was still developing the first industrial process to recapture the acid and, without a discharge permit, the titanium facility would close and put all employees out of work.

The Virginia Supreme Court ruled that, though the sulfuric acid pollution killed fish in the river, the discharge was legal under the state permit. The second violation was voided, after the court recognized the balancing act required of the members appointed to the State Water Control Board before issuing the first permits that authorized harmful pollution:4

Mining and titanium processing operations ceased in 1971. American Cyanamid Company relocated to Savannah, Georgia, where it had operated a plant since the mid-1950's.5

S. Vance Wilkins Jr. bought it in 1973. He sold it to a New Jersey corporation in 1976, one year before getting elected to the Virginia General Assembly and becoming the first Republican Majority Leader of the House of Delegates in 2000.

During his ownership, no titanium ore was mined or processed. Wilkins ensured the corporation who bought the property from him assumed all responsibility for any environmental remediation of the mining wastes, and he never had to pay any cleanup costs.

After the New Jersey corporation purchased the site, a swindler used it to obtain a fraudulent loan and bribe US Senator Harrison Williams. The swindler claimed he had obtained political influence sufficient to get the Department of Defense to order titanium and justify reopening the mine.

After an agent posed as an Arab sheik, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) obtained convictions of six members of the US House of Representatives and the New Jersey senator in the "Abscam" scandal. Both the supposed demand for titanium and the economic viability of reopening the Virginia mine were hoaxes.6

During the 40 years of processing the ore until the mill closed in 1971, waste material known as copperas was piled up next to the Piney River. The waste included iron and sulfur compounds that produced sulfuric acid in the runoff and the groundwater. During heavy rainfalls, fish kills were common.

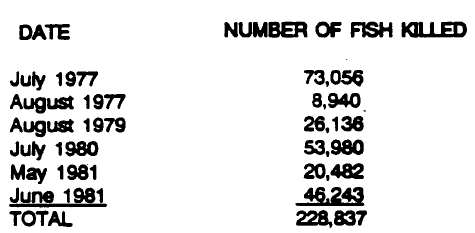

fish kills in the Piney River led to the US Titanium site being added to the Superfund list

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, Superfund Record of Decision: U.S. Titanium, VA (p.8)

In 1979, water flowing off the mining waste triggered another fish kill in the Piney River. Virginia officials forced the New Jersey corporation, US Titanium, to bury the mining waste in a landfill in Nelson County in 1980.

The cap on that initial landfill did not seal off the material adequately. Acidic groundwater flowed downhill from the pit, steadily killing vegetation and wildlife. The pH of seepage water was as low as 2.66. Iron precipitated out of the acidic leachate onto the bottom of the Piney River as ferric hydroxide sediment, disrupting the benthic community for over three miles.

a 2018 image shows reclamation of the American Cyanamid Company operations, downstream of an aplite quarry

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

After further study, in 1983 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) added the US Titanium site to the National Priorities List established by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). That law is known most commonly as the Superfund Act.

An essential step in getting Federal funds for cleanup is to be added to the National Priorities List. About 50 acres of the 175 acres used by the titanium dioxide manufacturing facility ended up classified as a Superfund site.

Simply replacing the clay cap to block water effectively from entering the landfill would not correct the problem. The buried copperas was saturated with water and slowly dissolving via oxidation and hydrolysis. As the copperas slumped, a new clay cap would sink and crack - and the copperas creating the risk would still be in place.

The adopted solution was to pump chemicals into the copperas and dissolve it within the landfill (in-situ). The next step would be to extract the leachate and chemically treat it to oxidize the iron and sulfur, then neutralize the solution and precipitate solids that would not be harmful. Finally, the treated water would be discharged into the Piney River and the precipitated material would be buried in a sealed landfill.

In addition, some overly-acidic soils in the area near the landfill would be neutralized. A groundwater treatment system would include an oxidation/settling pond, a constructed wetland, and a limestone neutralization bed to reduce pH before flowing int the Piney River. Total cost of the In-Situ Dissolution and Treatment alternative was estimated at $5,895,000.

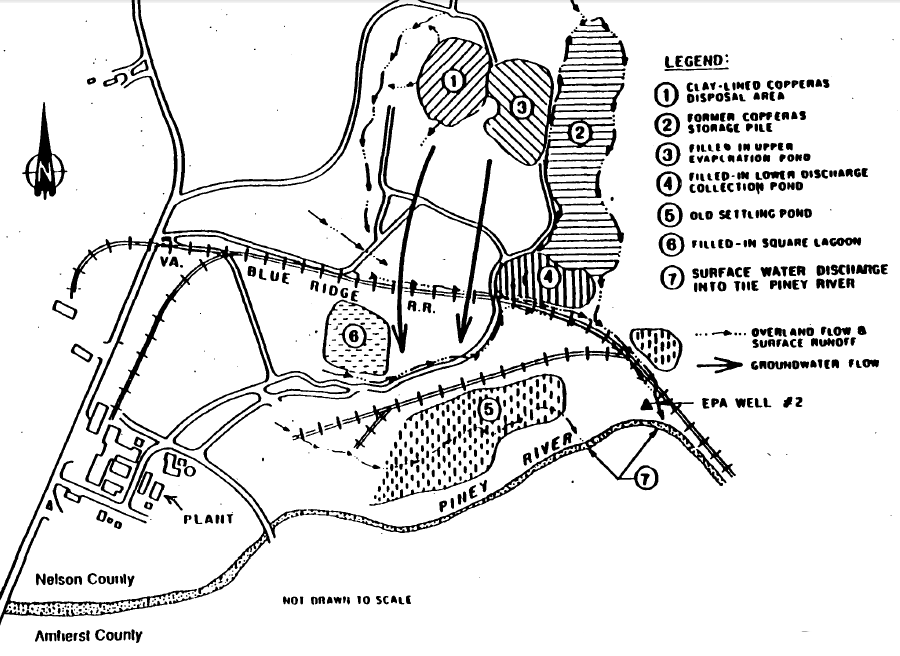

the Environmental Protection Agency identified spots at the US Titanium site that might generate heavy metal and sulfuric acid contamination

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, Superfund Record of Decision: U.S. Titanium, VA

The dissolution-and-treatment approach of the buried copperas removed the risk of future contamination by acidic groundwater discharge. It was not as dramatic or as expensive a "fix" as the only other alternative that would provide a permanent solution - excavate the landfill (Area 1) and chemically treat the copperas on the surface. In 1989, the Environmental Protection Agency estimated that full excavation and treatment to neutralize the copperas would cost $12,567,000.

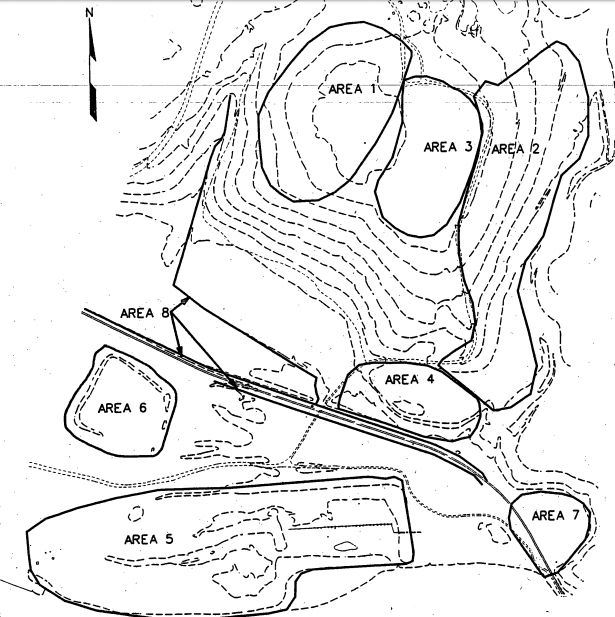

the 50-acre US Titanium Superfund site is in Nelson County, including Site 1 where mining waste (copperas) was buried in a landfill in 1980

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, Fourth Five-Year Review Report for the US Titanium Superfund Site (Figure 2)

The adopted alternative did meet the objectives of local residents. They had reacted strongly to a comment by a contractor for American Cyanamid Company, which was a "potentially responsible party" that would be required to pay for most of the remediation. The contractor and American Cyanamid Company proposed initially just adding more clay to the cap on the landfill, rather than treating the copperas directly. Just adding more clay would cost only $533,000.

There were no materials at the titanium processing site, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB's), which would be classified as "hazardous waste" under Subtitle C of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). The contractor had stated:7

One response summed up the local reaction:8

starting in 1996, acidic groundwater was neutralized in a tank before it was discharged into the Piney River

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Titanium Superfund Site Community Update (Spring 2017)

The Environmental Protection Agency's Record of Decision for treatment of pollution at the site was signed in 1989. The Federal agency, American Cyanamid Company, and the state of Virginia accepted a Consent Decree for the cleanup plan in 1991. In a 1993 corporate reorganization, American Cyanamid Company transferred responsibility for the site remediation to Cytec Industries Inc.

In 1995, the treatment process was modified. Soil and copperas from the landfill (Area 1) was excavated and neutralized on the surface, rather than through the in-situ dissolution that the Environmental Protection Agency had approved. In addition, a tank was constructed to treat ground water and the iron-rich sludge was then precipitated in a pond. Groundwater treatment has reduced iron concentrations in some areas in some areas, but as of 2015 some locations were still unacceptably low in pH (i.e., too acidic) and high in iron.9

In 2023, plans were announced for construction of a 50-megawatt solar facility on the site of the former titanium mine. Installing solar panels and connecting to the grid did not require use of groundwater, avoiding the constraint of dealing with old pollution. The director of development for Energix, the company proposing the project, said:10