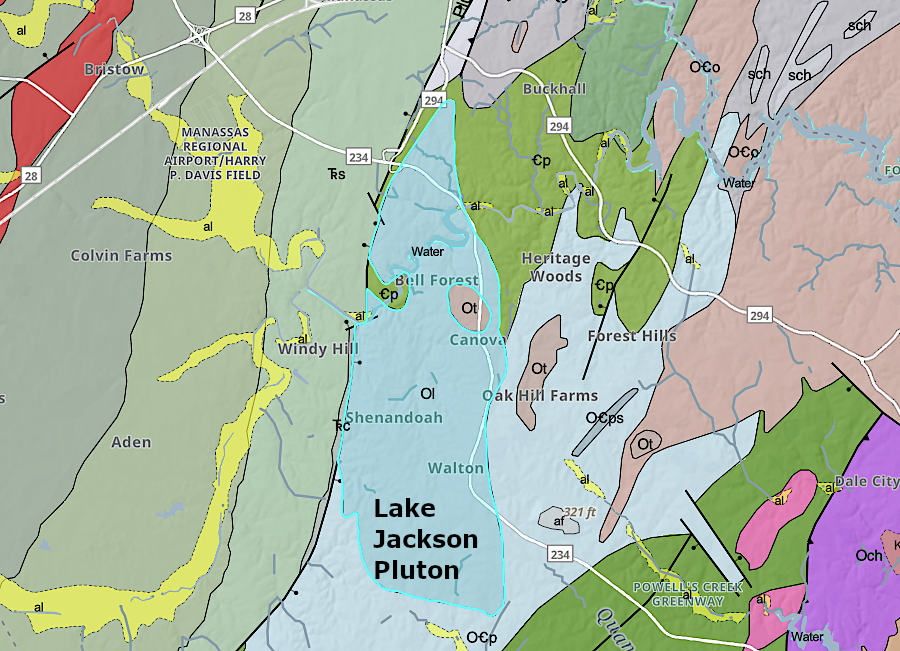

the Lake Jackson pluton in Prince William County crystallized deep underground around 450 million years ago

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Virginia Geologic Map (2021)

the Lake Jackson pluton in Prince William County crystallized deep underground around 450 million years ago

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Virginia Geologic Map (2021)

The bottoms of slabs of continental crust on tectonic plates are in contact with the hot mantle. If the slab of continental crust is thick enough to trap enough heat, as in the middle of a supercontinent such as Pangea, the bottom can melt. Supercontinents break apart as rising magma pushes chunks of continental crust in different directions.

Subduction also can carry continental crust deep enough to melt. Melted edges of subducting slabs of continental crust rise upwards, since the hot rock (especially if enriched with water) is less dense than the overlying continental crust.

Blobs of molten rock may rise in a shape that resembles an inflated balloon. The intrusive igneous rock pushes aside overlying layers of hard bedrock until a "balloon" of hot rock nears the surface. There the magma can be extruded as a basalt lava flow (when the percentage of silica is low) or can erupt as andesite/rhyolite in a volcano.1

A chamber of still-hot magma lies beneath all active volcanoes. The consistency of the buried hot magma is thick, more like honey or peanut butter than free-flowing water. If can flow to the surface when water and gas reduce the density. Beneath extinct volcanoes, the once-hot magma chambers have cooled and crystallized back into solid rock.

In Hawaii, the magma is 2,700°F when it starts to rise upwards. After eight years, rock that reaches the magma chamber two miles underneath the Kīlauea volcano has cooled to 2,200°F. The rock which is erupted onto the surface crystalizes and stops flowing at 1,830°F.1

At times, the rising hot rock will cool 5-10 miles beneath the surface as it reaches a height where it cools enough to recrystallize. When magma cools slowly, large mineral crystals are formed and the resulting rock is called granite. If the granite is altered by heat/pressure so different minerals align into layers, the rock is called "gneiss." Minerals are primarily orthoclase and plagioclase feldspars, quartz, biotite and hornblende. If there is less than 20% quartz, the rock is a quartz monzonite.2

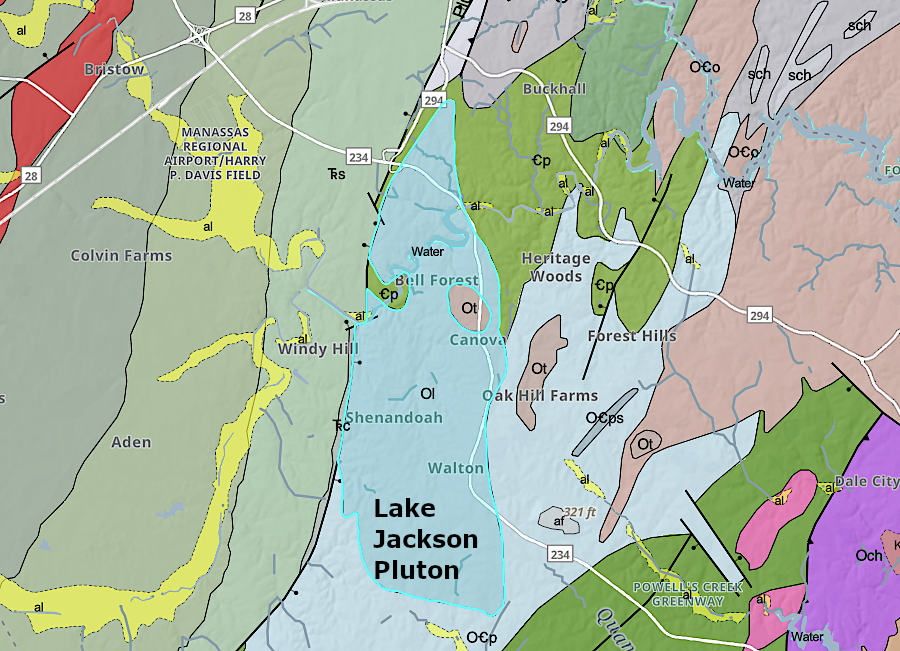

Blobs of deeply-buried granite/gneiss that intrude into overlying "country rock" are called plutons. They have a very consistent texture and mineral composition. If the igneous intrusion exceeds 100km2 (about 38 square miles) in size, often where multiple plutons have congealed next to one another, the term "batholith" is used instead. The Robertson River Igneous Suite in the Blue Ridge next to Shenandoah National Park includes at least eight plutons with different geochemistry.3

the Capital Beltway (I-495) crosses the Occoquan Batholith in Fairfax County

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Geologic map of the Annandale quadrangle, Fairfax and Arlington Counties, and Alexandria City, Virginia

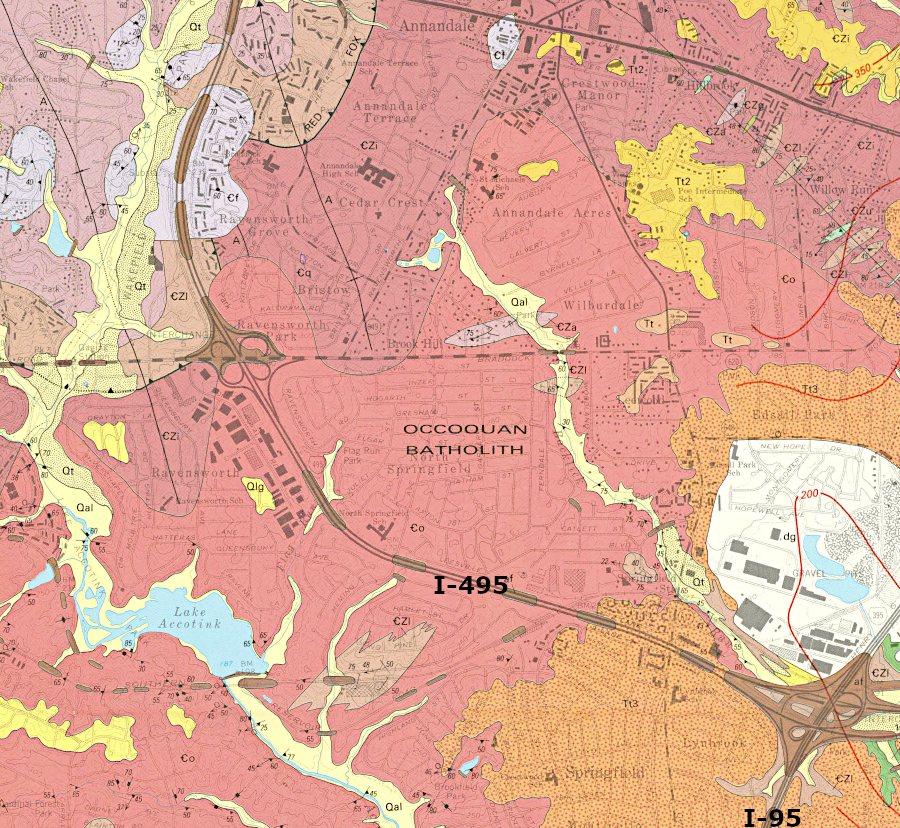

Some plutons have been exposed by erosion of the overlying materials. As the plutons near the surface, the pressure is reduced as the overlying rocks erode away. The edge of the pluton near the surface cracks like an onion, slowly peeling in a process called exfoliation. The core of the pluton remains intact with few fractures because plutons cooled so slowly that the magma did not differentiate into major zones of different minerals which fracture at different pressures.

In North Carolina, erosion has exposed plutons such as Looking Glass Rock. That magma rose upwards nearly 400 million years ago and cooled underground.

The quartz monzonite that forms Stone Mountain in Georgia is a pluton that formed 300 million years ago as the North American and African tectonic plates converged. The Stone Mountain pluton was originally 10 miles deep. It has been exposed over the last 15 million years, creating today's 750' high feature. Most of the pluton remains buried:4

plutons once buried as much as 5 miles deep, such as Looking Glass Rock, have been exposed by erosion

Source: Wikipedia, Looking Glass Rock

There are numerous plutons buried underneath the Piedmont and Coastal Plain of Virginia. Multiple plutons have been intruded into the Chopawamsic terrane, the "gold belt" of Virginia.5

In a few locations, the granite and quartz monzonite formation in plutons are exposed on the surface. None in Virginia have the dome-shaped appearance of an isolated monadnock, as seen in the Carolinas and Georgia.

The Petersburg granite is exposed in the bed of the James River at Belle Isle. It was emplaced deep underground in two phases, one 425-400 million years ago and another 320-300 million years ago as Pangea formed. The older rock, now called the Dinwiddie Terrane, formed in a peri-Gondwanan volcanic arc system in the Iapetus Ocean. It was accreted to edge of the North American plate around the time of the Acadian orogeny. The terrane was later pushed along the Hylas and Nottoway River fault zones, ending up adjacent to the Goochland and Roanoke Rapids terranes by the end of the Alleghanian orogeny 300 million years ago.6

Rock quarried at Belle Isle after the Civil War was used for paving streets with cobblestones and installing curbs in Shockoe Slip. Today the site is part of a city park.7