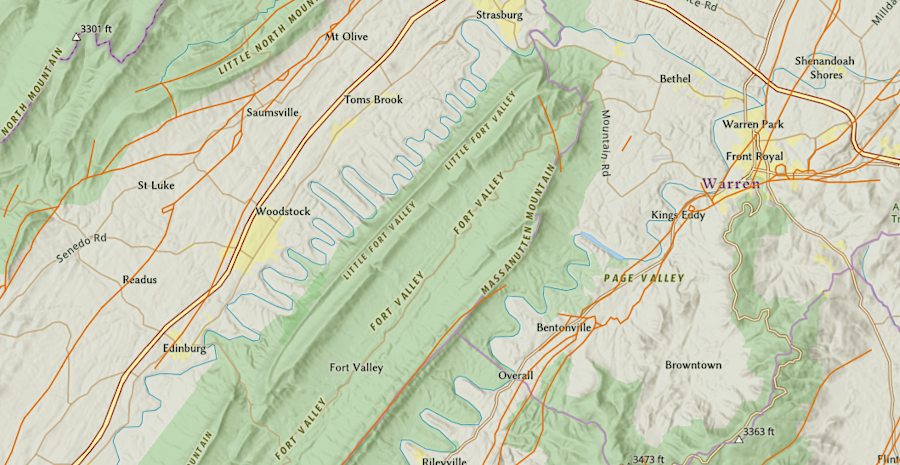

faults (brown lines) mark the uplift of mountains, dropping of basins, and compression of geologic formations through tectonic thrusting

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

faults (brown lines) mark the uplift of mountains, dropping of basins, and compression of geologic formations through tectonic thrusting

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The US Geological Survey defines a geologic fault as:1

Earthquakes are associated with the existence of a fault or the creation of a new one. Though faults are zones where blocks of adjacent bedrock have moved differently, the potential for modern movement varies. There are active faults in California, including the famous San Andreas Fault, with regular earthquakes and differential movement along the fault lines. Sensationalist movies portray cracks at the surface swallowing buildings and actors during earthquakes, but the locations for those hypothetical events are not in Virginia.

Virginia lacks a surface expression of a fault as dramatic as the San Andreas Fault in California

Source: Doc Searls, San Andreas Fault, on the Carrizo Plain

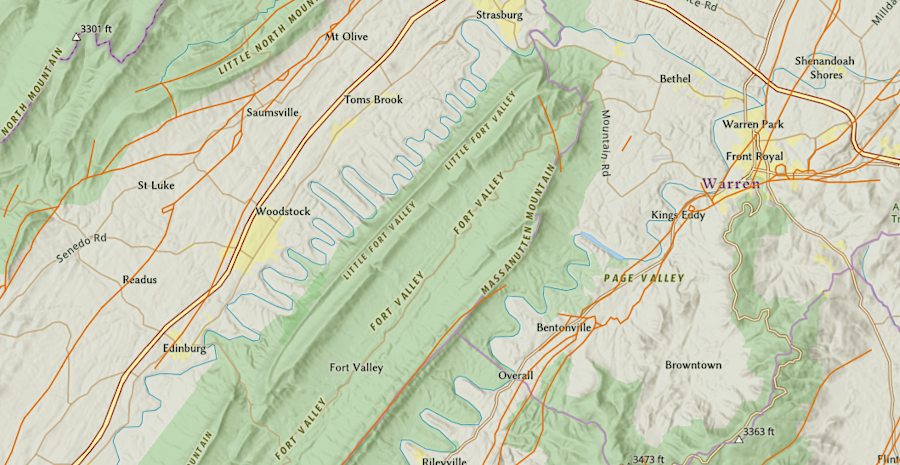

Few faults are mapped in the Coastal Plain sedimentary formations. They have accumulated since the breakup of Pangea, and for that entire time the edge of Virginia has been a passive margin. In contrast, faults are common throughout the Piedmont. That region was compressed during multiple orogenies over 200 million years as terranes were accreted onto the edge of Laurentia.

The compression during assembling of Pangea affected bedrock of Virginia all the way to the Alleghenian Plateau. Blocks of crust under pressure were thrust westward, moving the Blue Ridge perhaps 40 miles westward during the Alleghenian Orogeny when African crushed into North America. Thrust faults cracked the limestone and sandstone sedimentary layers deposited between the Cambrian Period and the Alleghenian Orogeny when the edge of Virginia was a passive margin, thrusting blocks on top of other blocks and reducing the width of Virginia.2

mapped faults (brown lines) are common west of the Fall Line in the Piedmont, but relatively rare in the Coastal Plain

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

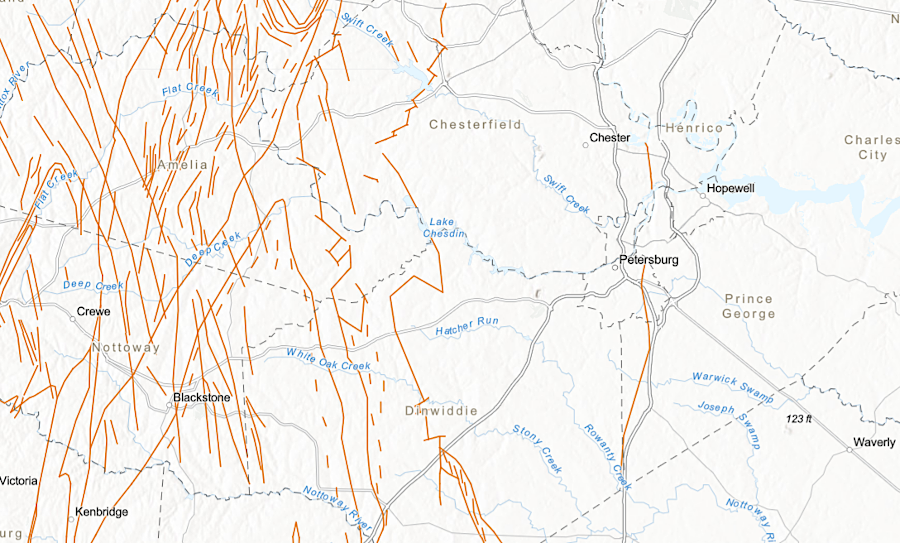

In southwestern Virginia:3

black lines depict faults along Pine Mountain

Source: Kentucky Geological Survey, Kentucky Geologic Map Service

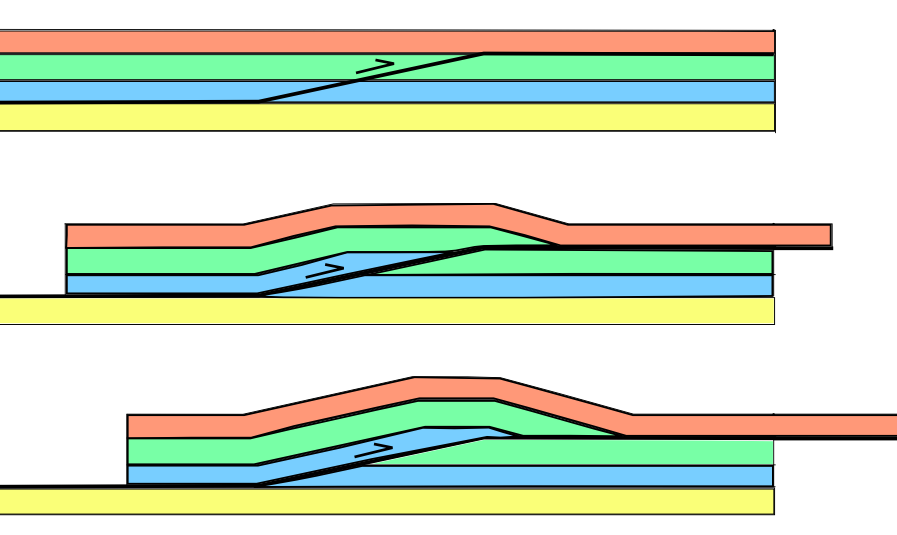

thrust faults displace layers of rock, stacking them on top of each other

Source: Wikipedia, Thrust fault (by Mike Norton)

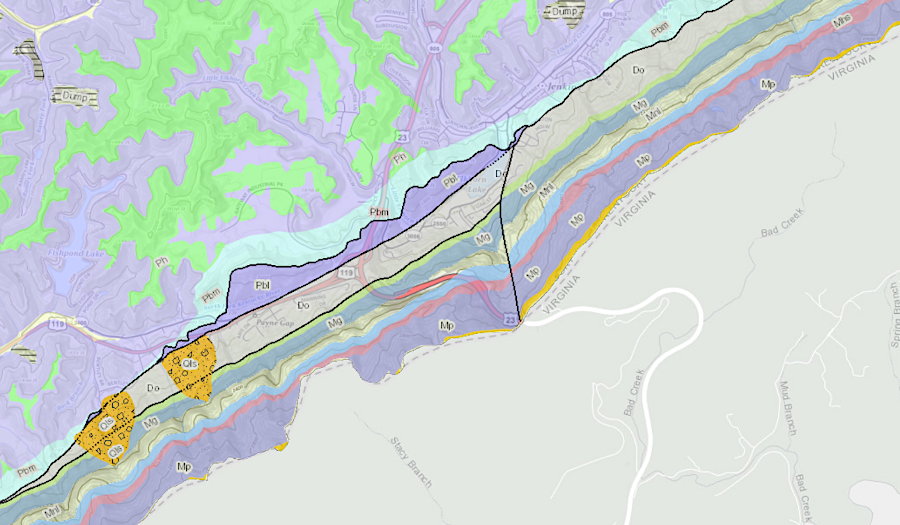

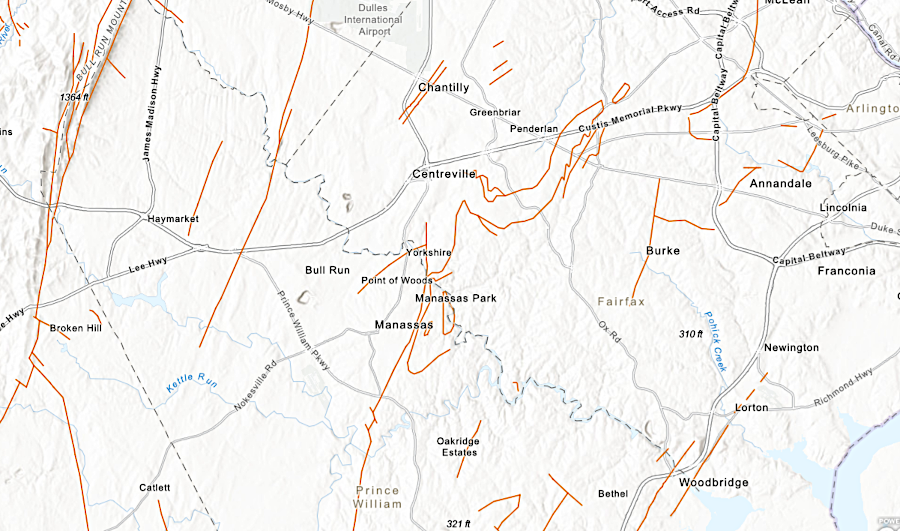

faults in Prince William County show the boundaries of terranes accreted to Laurentia, effects of the Alleghenian orogeny and breakup of Pangea, and slumping in the Coastal Plain

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online