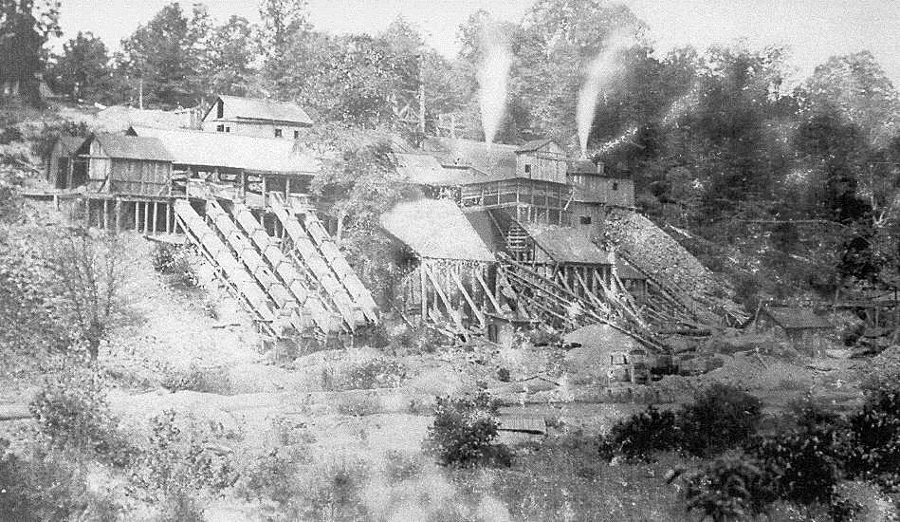

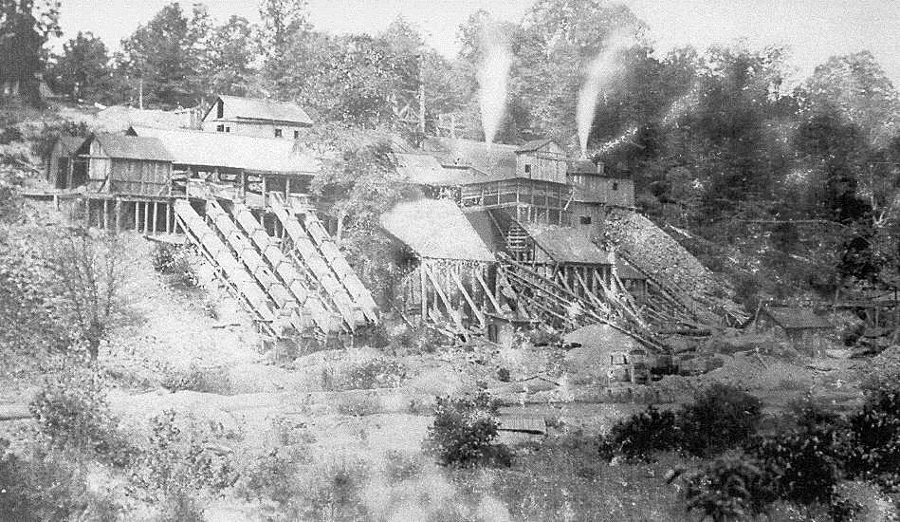

the Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine, now in Prince William Forest Park, produces sulfur from 1889-1920

Source: National Park Service, Archeology in the Prince William Forest Park

the Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine, now in Prince William Forest Park, produces sulfur from 1889-1920

Source: National Park Service, Archeology in the Prince William Forest Park

Mineralization of the bedrock along Quantico Creek occurred 460 million years ago. Volcanic and sedimentary rocks were metamorphosed as the Chopawamsic Terrane was formed from continental crust, and then transported and accreted to the edge of Virginia.

The pyrite deposit mined in Virginia may have formed before the Chopawamsic Terrane was attached to the North American continent, and long before the first dinosaurs or flowering plants evolved. The terrane was a chunk of continental crust similar to Madagascar or Indonesia today.

A mineralized zone enriched in gold, iron, and sulfur is located on the western edge of the Chopawamsic Terrane. Concentration of minerals in the gold-pyrite belt, stretching from Prince William to Louisa and Orange counties, may have been enhanced when the Chopawamsic Terrane crushed against the Western Piedmont/Potomac Terrane in the Iapetus Ocean while still not attached to "Virginia," or during the Taconic Orogeny when the terranes were accreted to the edge of the continent, or during the Alleghenian Orogeny when Pangea was formed 310-280 million years ago.1

iron-loving bacteria still create a brown slime at the bottom of Quantico Creek

The presence of ore worth mining was not identified until after the Industrial Revolution made sulfur a valuable resource. Shiny "fools gold" was spotted at the confluence of Quantico Creek and South Branch Quantico Creek in the 1880's. The ore deposit stretching almost 1,000 feet along Quantico Creek turned out to be one of the largest in the United States.

The Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine opened in 1889. The Cabin Branch Mining Company was initially a small business managed by the local Detrick and Bradley families.

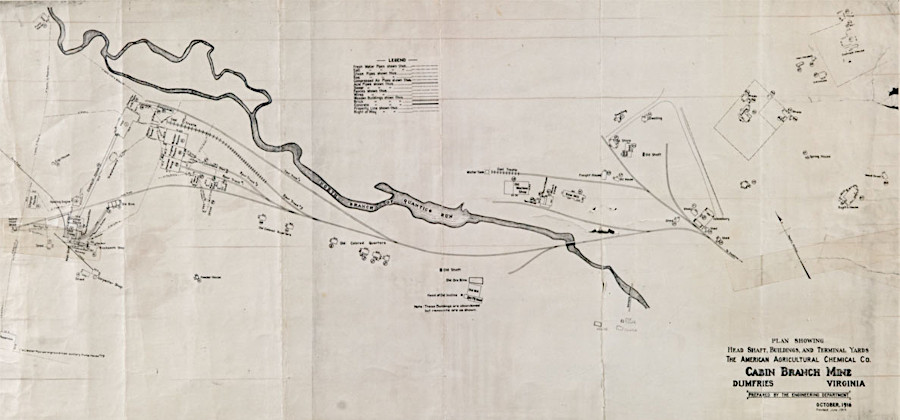

The price for sulfur rose when World War I started, since sulfur is a key ingredient in gunpowder. The American Agricultural Chemical Company purchased it in 1916. That corporation expanded the mining to the west, going upstream on the North Fork of Quantico Creek. The area worked by the Cabin Branch Mining Company is described by National Park Service rangers as the "family side," while the western edge is called the "company side."

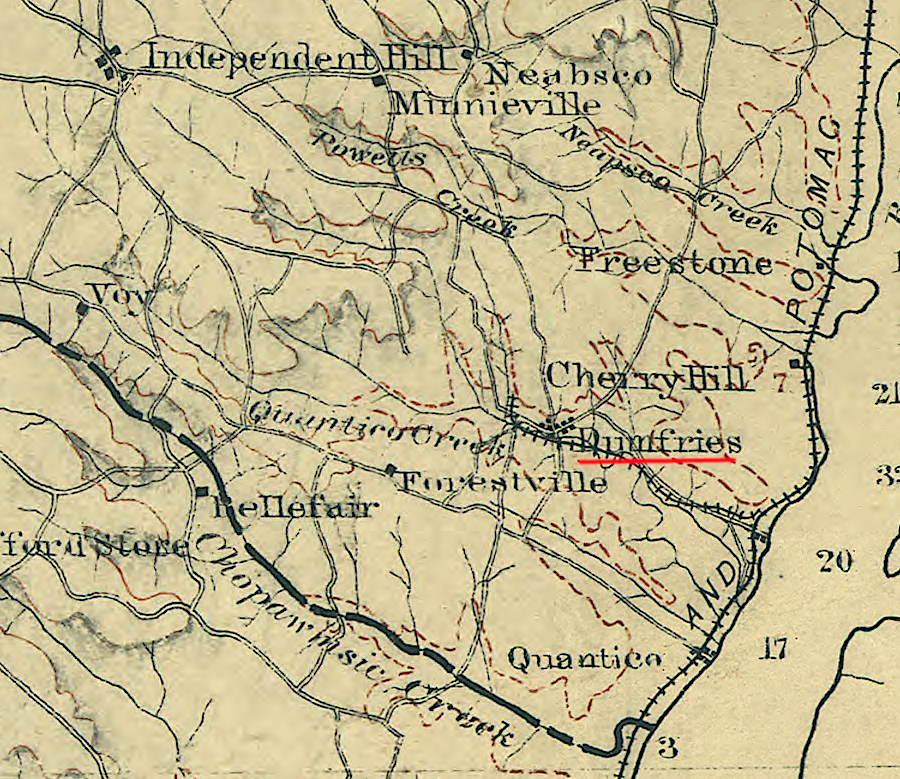

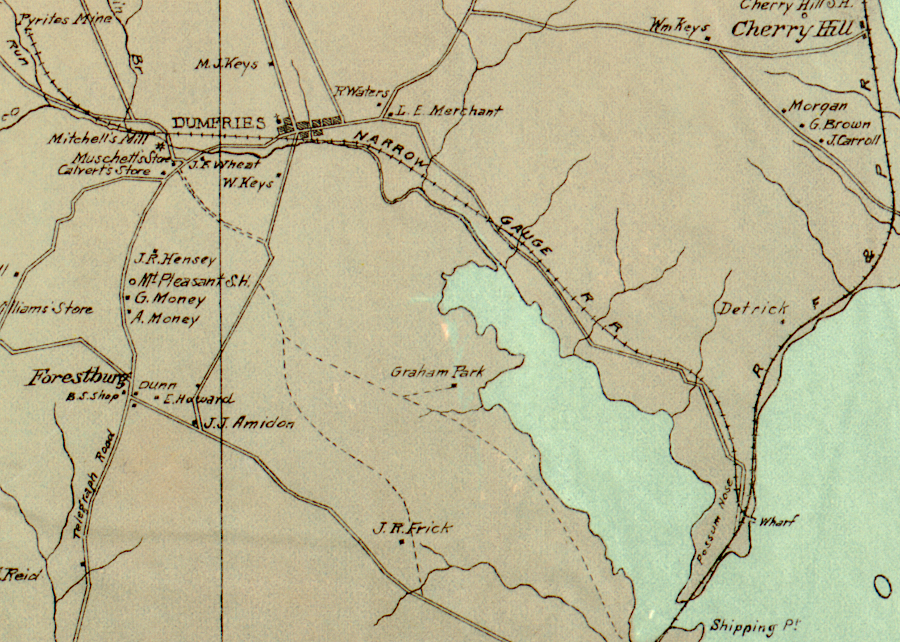

A railroad carried the ore to a wharf on Possum Point, from where it was shipped on boats to a smelter. Though the iron rails have been removed and the wooden ties have rotted away, the level beds of multiple spur tracks are still evident along Quantico Creek. Batestown Road, known for years as Mine Road, follows the route of the railroad outside the boundaries of Prince William Forest Park.

the Cabin Branch Mine had a narrow gauge railroad connection to Possum Point

Source: Library of Congress, Map of northern Virginia (1894); Map of Prince William County, Virginia

Local subsistence farmers, including African-Americans from Batestown and white residents from Joplin, were hired to excavate the ore. Residents of both races came from the closest community to the mine, Hickory Ridge. There were six African American dormitories, perhaps built by the original Cabin Branch Mining Company. Throughout the life of the mine, housing was segregated.

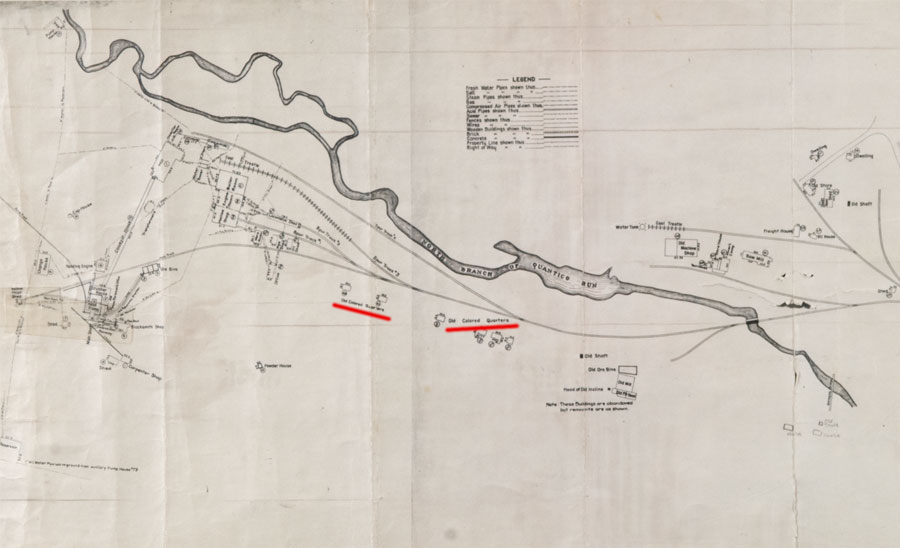

a 1916 map of the Cabin Branch Mine identified the locations of Old Colored Quarters, reflecting how miners were segregated

Source: National Park Service, Map of Cabin Branch Mine (1916)

The miners worked 10-12 hour shifts at the mine, in addition to managing their farms. The American Agricultural Chemical Company created a company town that provided housing and a company store for the workers who did not live on a nearby farm. Some payment for mining operations was in company script, which could be used only in the company store to purchase food and other products sold at the company's prices.

At least seven shafts were dug by the two sets of owners, plus perhaps an eighth shaft to provide ventilation. One shaft may have been used to pump groundwater out of the mine, enabling the miners to drill and pick ore from the deposit. Tailings (piles of waste rock, excavated in order to extract the pyrite-rich ore) and buildings were located on both sides of the creek.

vent from Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine, before site was reclaimed

Source: National Park Service, Prince William Forest Park Facebook post (April 23, 2025)

After the war, the price for sulfur dropped. Demand declined and new sources of elemental sulfur were developed, making the Cabin Branch Mine only marginally profitable.

In 1920, workers demanded a pay raise of $0.50/day at a time when wages were $3.50/day and $4.50/day. Instead of increasing wages, the American Agricultural Chemical Company closed the mine. Reportedly, a mine manager declared to the workers:2

It turned out that Quantico Creek and the water-filled mine shafts were not suitable for frogs. The sulfur in the waste rock altered the water chemistry, making the wetlands and stream a hostile habitat for amphibians and fish. The pyrite tailings continued to oxidize, creating a weak sulfuric acid which flowed into Quantico Creek. At the mine site, the water pH was 3.8, as acid as vinegar.

Heavy metals leaching out of the tailings have been concentrated in streambed sediments for a century. Heavy storms have redistributed the sediment downstream, affecting water quality east to the confluence with the Potomac River.

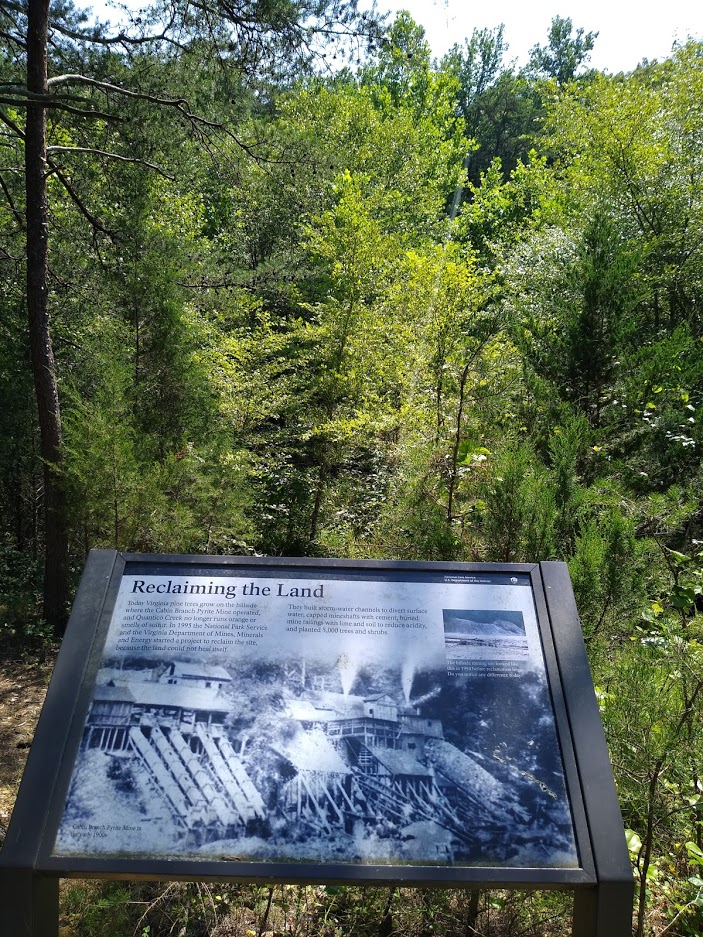

Most of the major site reclamation project was completed in 1995. Mine openings were capped with concrete, with dirt and lime placed on top of the tailings. New ditches diverted stormwater away from the old tailings.

site of most Cabin Branch Mine shafts before reclamation in the 1990's

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 076-0289 Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine Historic District (1894)

One of the capped mine shafts is readily visible to hikers in Prince William Forest Park using the North Valley Trail. The concrete caps are marked by metal pipes:3

a capped mine shaft at the Cabin Branch pyrite mine on Quantico Creek, now inside Prince William Forest Park

Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) was planted where new soil was placed on top of old "tailings," the waste rock separated from the pyrite ore and piled up near the mine shafts. Some piles were left untreated, and pine trees have managed to grow on them anyway. Spots along Quantico Creek where there are just a sparse population of Virginia pines are locations where tailings were piled up.

Mine tailings may have been used to build the dam for Carters Pond within Prince William Forest Park. Use of that acidic rock may explain the lower-than-average index of fish biological integrity in Carters Run, a tributary to Quantico Creek. Rock from the mine tailings was probably used for multiple construction projects within the Dumfries area, including house foundations within what is now Prince William Forest Park.

A boardwalk made from plastic boards was constructed on the northern side of Quantico Creek in 1999, following a portion of the railroad bed and passing through the site of the sawmill. The pH of Quantico Creek has risen to normal levels, but within the stream sediments remain contaminated with aluminum, cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, manganese, nickel, silver, and zinc. The reclamation effort created artificial vernal pools that amphibians quickly colonized. However, salamander reproduction in those wetlands was quite low due to the acidity and toxic metals dissolved in the water.

On the shoreline, the National Park Service has noted:4

hikers on the north bank of Quantico Creek pass through the site of the old sawmill, and follow the old railroad bed

The success of the reclamation has obscured the historical use of the site. By 2021, trees planted on the tailings piles in 1995 had grown high enough to block the once-clear view from the boardwalk to the mill complex and shafts driven into the high bank on the south side of Quantico Creek. Interpretive signs installed the National Park Service are now necessary for a visitor to understand the unique character of the old Cabin Branch Mine site. What was once a barren, noisy industrial site, particularly between 1916-1920, had been converted to a quiet stream valley that is not clearly different from stream valleys elsewhere in Prince William Forest Park.

the view of the old mine shafts across Quantico Creek has been obstructed by successfully planting trees to reclaim the site (2021)

The reclamation of the landscape transformed the shafts and tailing piles. New vegetation has enabled wildlife to thrive, but concrete foundations and other remnants of historical structures still remain. The nomination form of the pyrite mine site to the National Register of Historic Places concluded that the reclamation effort had not destroyed the archeological integrity of the district:5

concrete foundations show the location of old buildings constructed by the American Agricultural Chemical Company

acid runoff from pyrite mining killed vegetation along Quantico Creek

Source: National Park Service, Virtual Museum Exhibit

in 1916 there were 70 buildings (including six segregated dormitories for black workers) on 88 acres at the Cabin Branch Mine

Source: National Park Service, Map of Cabin Branch Mine

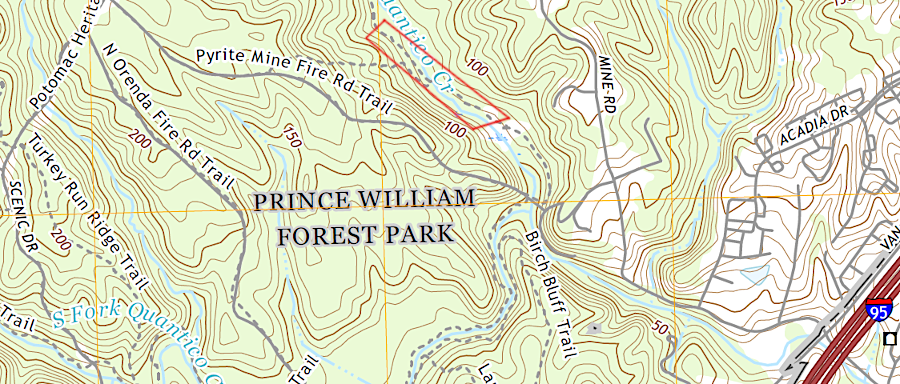

hikers can reach the old Cabin Branch Mine site (red box) by following a 1.2-mile trail in Prince William Forest Park

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Quantico, VA 1:24,000 topographic map (2019)