the annual Pony Swim at Chincoteague is a major tourist event

Source: US Fish & Wildlife Service and National Park Service, Your New Beach Experience (July 2017)

the annual Pony Swim at Chincoteague is a major tourist event

Source: US Fish & Wildlife Service and National Park Service, Your New Beach Experience (July 2017)

The US Fish & Wildlife Service and the National Park Service, the two Federal agencies responsible for natural resource management on Assateague Island, support management rather than elimination of a non-native, introduced species there - horses (Equus ferus).

The ponies graze on salt hay composed of marsh and dune grasses - primarily saltwater cord grass (Spartina alterniflora), American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata), and three-square sedge (Scircpus americana). They impact natural resources that otherwise would be used by native species.

Due to the economic benefits for Chincoteague and Ocean City from tourism, both Federal agencies and the Maryland State Parks help to maintain feral herds on Assateague Island. The National Park Service has classified their free-roaming herd of wild horses as a "desirable exotic species."

The wild ponies live in harsh conditions that keep them from growing large enough (14 hands or 56" high) to qualify as "horses." As a year-round diet, the salt hay has limited food value. Horses living on it are stunted in their growth, resulting in pony-sized animals. Their small size and great endurance were publicized prior to the Civil War:1

Local lore includes the exotic potential of horses being introduced to Assateague Island by pirates. That is a more romantic story than saying the Chincoteague ponies are just the descendants of horses brought by the colonists in the 1600's and 1700's.

the Spanish brought horses to the New World in the 1500's, but those on Assateague Island may be from English colonists

Source: Federal Highway Administration, 1539 Coming of the Horse (painting by Carl Rakeman)

A more realistic, but still exotic, possibility is that some horses were on the Spanish ship La Galga when it wrecked on the island in 1750. Documentation of such a shipwreck is thin, but genetic evidence connects Spanish and Assateague Island horses. DNA has been extracted from a fossilized horse tooth found at a Spanish colony in Haiti, dating back to the early 1500's. The DNA reveals that the most closely related modern horses to those early Spanish horses are the feral animals on Assateague Island.

By 1750, the Eastern Shore had been settled by English colonists for over a century. The first horses of colonists were released on Chincoteague and Assateague islands in 1669, long after the first European (Giovanni da Verrazzano) visited the area in 1523.

The National Park Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which share ownership of Assateague Island, highlight the probability that the original source of today's ponies are horses released by, or escaped from, those early English colonists rather than Spanish explorers or pirates. The colonists were farmers, and they moved horses to Atlantic Ocean and Chesapeake Bay islands for multiple reasons. The salt hay provided seasonal forage, there was no need to build expensive fences on the islands to keep horses from damaging crops, and isolating livestock provided the potential to minimize/avoid local taxes.2

The Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge was created in 1943 to enhance habitat for ducks and geese, not feral horses. Approval for purchasing the initial 8,808 acres came from the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission. However, pony roundups were an annual event on Chincoteague Island long before the Federal government acquired the refuge land.

The 1962 Ash Wednesday storm created an opportunity for the National Park Service and US Fish and Wildlife Service to eliminate the non-native ponies. Main Street in the Town of Chincoteague was flooded with 6 feet of water, and most of the ponies on Assateague Island drowned. The horses had sheltered in the forests and gathered in clusters with their butts to the wind, but the storm surge rose too high.

The Federal agencies were responsive to local concerns regarding the value of the wild horses. Rather than eliminate the unique attraction that draws many tourists to Chincoteague, the herd was restocked. Today, there is no politically viable option for eliminating the non-native ponies.3

The benefits of owning horses were recorded in an 1877 article in Scribner's Monthly:4

catching a pony, 1877

Source: Scribner's Monthly, Chincoteague

Animal roundups on Assateague Island have been standard operating procedure since the 1700's. The free-ranging horses were gathered and marked to define ownership of the new colts born each year. Ownership of the sheep also had to be defined, since the livestock was private property rather than community-owned herds:5

The National Park Service owns and manages the horses on the Maryland side of the island. When the Assateague Island National Seashore was added to the National Park Service system in 1965, there were 10 horses on the Maryland side. The National Park Service acquired ownership of the horses in 1968, at which time there were 28, and the population grew naturally by 10-15% annually.

Excessive grazing reduced the saltmarsh cordgrass (Spartina alternafiora), American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata), and three-square sedge (Scirpus americana) in wetland and dune habitats. Natural resource managers determined in 2006 that the impact on natural vegetation of a herd totaling 80-100 horses would be acceptable. The National Park Service uses an immunocontraceptive vaccine, Porcine Zona Pellucida (PZP), to manage the fertility of mares on Assateague Island National Seashore.

excessive grazing by the non-native horses can damage the dune and wetland habitats

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Chincoteague ponies and cattle egrets

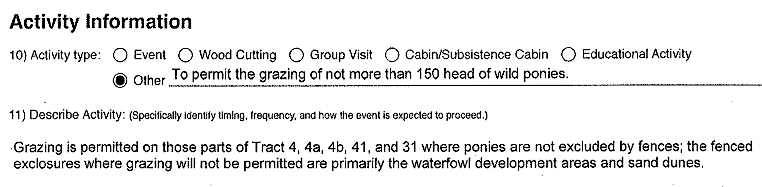

The US Fish and Wildlife Service uses a different approach to manage the population within the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. Each year, mares on the Virginia side of Assateague Island the produce around 70 foals. Those horses are owned by the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company, but the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service maintains the population at around 150 animals by authorizing the sale of some ponies each year.

Starting in 1925, the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company began rounding up the herd on Chincoteague Island and selling young ponies. After World War II, they moved the ponies to Assateague Island. Since 1946, the US Fish and Wildlife Service has issued a grazing permit to the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Grazing permits for private owners were phased out in the early 1950's.

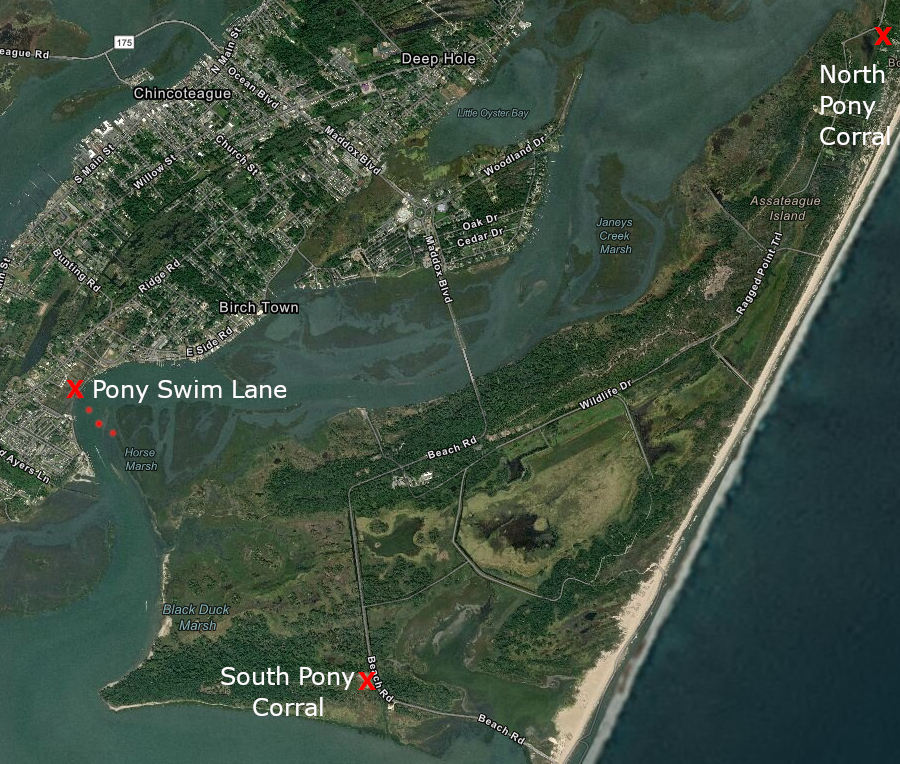

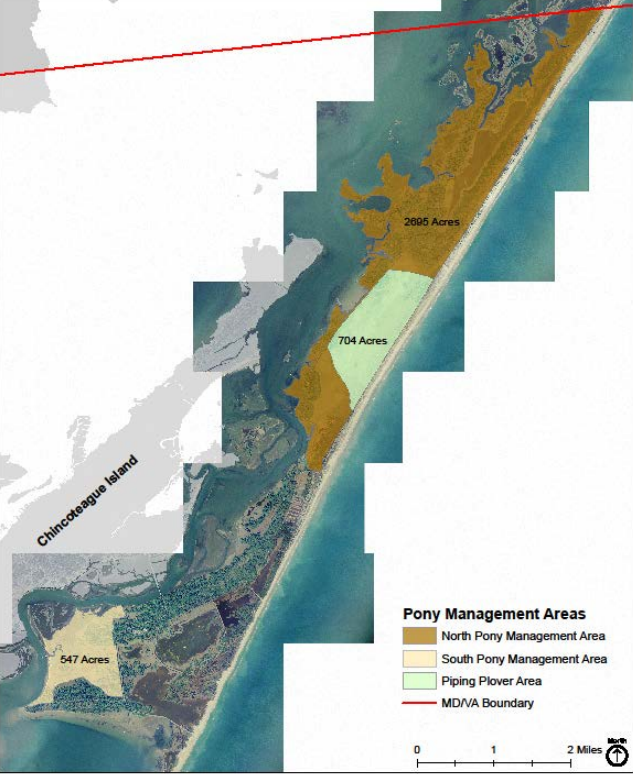

The last Wednesday of July is a major tourist event, the annual Pony Swim. The process starts by rounding up all of the horses in the Virginia portion of Assateague Island. "Saltwater cowboys" move the horses living on the Northern Management Unit (3,300 acres) of the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge into the northern corral. Horses living on the Southern Management Unit (547 acres) are placed in the south corral. Movement is controlled by 13 miles of fences. Gates are opened in advance of hurricanes to allow ponies to move to the highest ground, when a roundup and relocation is conducted.

Two days before the swim, the northern herd is moved south along the Atlantic Ocean beach to the south corral at sunrise. If there are piping plover chicks or nesting sea turtles on the beach, the Pony Walk route is modified. From that location, most of the ponies are forced to swim across the narrow channel over to Chincoteague Island.

traditional Pony Walk route from the North Pony Corral on the Monday before the Pony Swim

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Interim Chincoteague Pony Management Plan," Appendix D in "Chincoteague and Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuges - Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement (p.D-50)

Visitors grab a spot on the Chincoteague Island shoreline as early as 3:00am on the day of the swim. At slack tide, when the current in the Assateague Channel is minimal, the ponies swim over to Chincoteague Island and walk to the pen at Pony Swim Lane. The swim requires less than five minutes, and the adult ponies are experienced swimmers from previous years. Mares with foals too young to swim are trucked across the causeway to the pen.

On Thursdays, 60-90 young foals are auctioned to raise funds for the volunteer fire department. Some bidders on the ponies agree to participate in "buy back" sales. The purchased foal will be returned to Assateague Island in order to maintain the herd, but the buyer gets to give the pony its name in exchange for buying it.

On Friday, the stallions and mares in the southern herd swim back to Assateague Island. Adult ponies in the northern herd are trucked back. The bidders who purchased a foal take it away, except those too young to be separated from their mothers yet. Those foals are kept in the pen with the mares, and transferred to purchasers when more mature.6

ponies from the north corral are moved to the south corral on Monday, then on Wednesday both herds swim across the Assateague Channel to emerge at Pony Swim Lane

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Marguerite Henry traveled to Chincoteague in 1945 to see the roundup. The next year, Henry purchased a palomino pinto colt named "Misty" from the Beebe Ranch on Chincoteague Island and had her shipped to her home in Illinois. In 1947, Marguerite Henry published Misty of Chincoteague, and it became a classic children's book. Her story was based on the real-life experiences of young Paul and Maureen Beebe raising horses at the Beebe Ranch.

Misty was shipped back to Chincoteague in 1957 in order to breed, and kept at the Beebe Ranch. Misty was pregnant during the Ash Wednesday storm in 1962. The humans evacuated to Wallops Island as water flooded most of Chincoteague, and Misty rode out the storm in the kitchen of the Beebe house. She was fortunate; about half of the 300 ponies on Assateague Island drowned during that storm.

Her foal was named Stormy in recognition of the Ash Wednesday storm. Marguerite Henry wrote a sequel titled Stormy, Misty's Foal. Misty and her foal Stormy are now stuffed and on exhibit at the Museum of Chincoteague Island.7

The herd on Assateague was restocked after the Ash Wednesday storm, using foals that had been sold in earlier pony pennings. The Chincoteague pony breed was registered in 1994, but over time, Morgan, Welsh, Shetland, Arabian, and Mustangs have been added to the herd. Foreign stock was introduced after equine infectious anemia reduced the population significantly in 1978.

The annual Pony Swim in the last week of July has become a major tourist event. Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge gets up to 1.5 million visitors a year, making it one of the top five most visited National Wildlife Refuges in America. The fireman's extended annual carnival attracts visitors to see ponies throughout the month of July. A tourist from Boston described the experience in 2019:8

One Saltwater Cowboy commented:9

The 1962 Ash Wednesday storm ended plans for developing Assateague Island into a resort. Federal acquisition of the property and creation of the Assateague Island National Seashore followed in 1965, 22 years after creation of the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. The National Park Service was given responsibility for the new seashore, and what is now called the US Fish and Wildlife Service manages the wildlife refuge.

The National Park Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service maintain a 0.75 mile fence at the Virginia-Maryland boundary, separating the ponies. Assateague Island stretches for 36 miles from Sinepuxent Bay in the north to Chincoteague Bay in the south; about 9 miles are in Virginia and 27 miles are in Maryland. Until 1986, "problem horses" that bothered humans on the National Park Service side of the fence were transferred to the US Fish and Wildlife side. The genetics of the herd have been mixed.

The herds on either side of that fence are managed by different techniques, based on the separate management objectives of the two Federal bureaucracies. The Maryland herd is owned by the National Park Service, while the ponies grazing on the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge is owned by the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Department.

The Chincoteague roundup reduces the population of the herd on the Virginia side of Assateague Island each year to about 150 adult ponies, the authorized limit in the Fish and Wildlife Service permit. In 2012, there were 22 stallions and 112 mares.10

the US Fish and Wildlife Service permits grazing for a maximum of 150 ponies

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Interim Chincoteague Pony Management Plan," Appendix D in "Chincoteague and Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuges - Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement (p.D-34)

Th Maryland ponies are not involved in the annual swim or auction of foals on Chincoteague. In 1968, there were 21 stallions and 61 mares roaming on the Maryland side of the fence.

The National Park Service maintains the population of the herd in Maryland below 100 animals by use of contraception. No roundups are required in Maryland; population levels are maintained by non-capture techniques. Birth control is accomplished by shooting mares with darts loaded with a vaccine that prevents pregnancy, but does not alter hormones and thus does not affect herd dynamics.11

visitors to the beach on Assateague Island often stop on the causeway to see the Chincoteague ponies

A plant pathogen common in the island marshes is a threat to the health of the fillies and mares, but for unknown reasons not the stallions. Pythium insidiosum is an oomycete, equivalent to a water mold or fungus. Most horses seem unaffected by it, but between 2017-2019 it killed eight of them from what locals called "swamp cancer."

To minimize the infections, barbed wire fences were replaced. The fences protected shoreline vegetation from overgrazing and accelerated shoreline erosion, but the barbs created small wounds in the hide of horses who pushed though in order to eat the marsh grass "right down to very, very small stubble."

The Chincoteague herd has been vaccinated against the pathogen, boosting the immune system to block the growth of its filaments inside the horses' bodies. Starting in 2020, a booster shot was added during the Spring Roundup. Humans are also at risk of being infected.

The 2020 Spring Roundup was altered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Fewer Saltwater Cowboys were used to round up the 160 ponies for health checks and to vaccinate the foals born over the winter, and the event was closed to the public. There was less help for local veterinarian doing the inoculations. Researchers stayed away because the influenza virus threatened humans as Pythium insidiosum threatened the ponies.

The Pony Swim was cancelled the first time since World War and the pony sale was scheduled as an online event. Bidders could see profiles for each pony, and had a week to bid.

The volunteer fire company, which had completed an expensive new fire station in 2019 and did not rely upon tax revenue, projected it could lose $500,000 in expected income. Instead, the auction set a new record, raising $388,000. The previous record had been $279,000 in total sales.

The Pony Swim was cancelled again in 2021 as the pandemic continued. Organizers were unwilling to risk the funding required to prepare for 40,000 visitors, in case such gatherings might be banned to prevent transmission of the virus. The tourist event was restarted in 2022, and the shoreline was crowded as usual again.

In 2023, the General Assembly designated the Chincoteague pony as the official state pony. The wild ponies which roam through Grayson Highlands State Park and Mount Rogers were mentioned in the discussion, but the designation was clearly designed to enhance tourism at Chincoteague.

The 2022 auction raised $450,000 for the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company. Some of the winning bids came from people online, but most were from people attending in person.

At the 99th auction in 2024, 200 Chincoteague swam across the channel in about five minutes. That year, 88 ponies were sold to raise a record $547,000. A descendant of Misty was sold for $50,000. The lowest price that year was $1,600 for a pinto colt.

it takes only four minutes for the ponies to swim from Assateague Island to Chincoteague

Source: Defense Visual Information Distribution Service (DVIDS), Coast Guard Station Chincoteague helps ensure safe 91st Annual Pony Swim

Another large crowd gathered early for the spectacle of the 100th anniversary swim in 2025. People stood in the muck on the shoreline near Pony Swim Lane for hours to get a good view of horses swimming for four minutes, herded by the local firefighters known as Saltwater Cowboys. The Chincoteague mayor told one group:12

Maintaining the horse herds could accelerate the impacts of sea level rise on Assateague Island. Assuming a one-meter sea level rise by the year 2100, approximately 57% of the salt marsh could disappear. Impact would be greater on the US Fish and Wildlife Service component, the portion of Assateague Island managed by the National Park Service has a higher percentage of more upland shrub/scrub and pine forest. The National Park Service has concluded:13

there are northern and southern pony management areas on Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Interim Chincoteague Pony Management Plan," Appendix D in "Chincoteague and Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuges - Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement (p.D-31)

There is the potential for another hurricane to wipe out the horse herd, perhaps even more thoroughly that the Ash Wednesday storm in 1962.

In 2019, Hurricane Dorian created a storm surge in North Carolina's Pamlico Sound. Water rose eight feet within an hour in a "mini-tsunami" and drowned 28 of the 49 wild horses on Cedar Island. Some carcasses washed up on the Core Banks of Cape Lookout National Seashore; others just disappeared into the waters of the sound or were carried into the Atlantic Ocean.

Each horse had an individual name associated with an island resident, and biologists had anticipated the herd would be the source for restocking other more-exposed islands if a hurricane wiped out their wild horse populations. None of the wild horses in the herds at Shackleford Banks and at Corolla died in Hurricane Dorian.

After Hurricane Dorian passed, local residents assumed that the 20 or so wild "sea cows" that had also roamed Cedar Island were drowning victims as well. However, a month after the storm, three cows were discovered at Cape Lookout.

They had managed to float/swim for four miles during the hurricane that swept across the Outer Banks. The National Park Service did not allow the non-native animals to stay. The Federal agency rounded up the cows and transported them back across Pamlico Sound via barge to their range of 1,000 acres of private land on Cedar Island.14

three of the herd of wild cows on Cedar Island survived being washed four miles to Cape Lookout

Source: National Park Service, Storm Watch

the feral cows that floated across Pamlico Sound in Hurricane Dorian were transported back via barge

Source: National Park Service, Ferry takes horses and cattle trailers back to the mainland

The National Park Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service have been unable to eliminate the non-native horses from Assateague Island, or the Corolla herd south of the Virginia-North Carolina boundary at False Cape State Park. Public support for the feral horses has forced the Federal agencies to modify their management plans to include preservation of the horse herds.

The National Park Service also failed in its attempt to remove feral horses from Cumberland Island, after that island off the Georgia coast became a "national seashore" in 1972. The first horses on the island may have been introduced by the Spanish in the 1500's. When the national seashore was designated, horses maintained as free ranging livestock after World War II had become wild. They were roaming freely, with no one providing food, medicine, or other care.

In the 1990's, the National Park Service concluded that the environmental damage caused by grazing and trampling should be ended by limiting the size of the herd to 120 horses, and removing the rest. Strong public objections blocked implementation of the plan.

Today the National Park Service estimates there are 120-180 wild horses on Cumberland Island. Their hooves destabilize dunes and streambanks and their grazing reduces the biodiversity of native plants and wildlife, in places reducing by 98% the grasses, sedges, sea oats, and cordgrass. The Federal agency tried again in 2015 to remove the herd, but once again discovered that it was not politically feasible.

The National Park Service as chosen to leave the horses on Cumberland Island to the whims of nature, so at times they are malnourished. On Cumberland Island, there is no annual roundup followed by a pony swim to reduce the number of horses to match an ecologically-based carrying capacity of the island's ecosystems. No veterinarian services are provided. The natural life expectancy of the horses is 9-10 years, before they die from disease, parasites, starvation during drought years, or simply old age.

The National Park Service has summarized the status of the herd:15

Maintaining a herd of bison on Catalina Island offers a similar challenge to the Catalina Island Conservancy. In 1924, 14 bison were transported to the island in the Pacific Ocean near Los Angeles for use in two Hollywood movies. The herd grew naturally to 550 animals by the 1980's, and became a tourism magnet attracting visitors to the island.

To reduce ecological impacts from excessive grazing and the transport of invasive species seeds on the shaggy buffalo coats, the Catalina Island Conservancy reduced the herd's size by shipping animals back to the mainland. In 2009, the organization started a contraception program for cows as a new technique for maintaining the population. No calves were born after 2013, and the population dropped to 100 by 2020. To maintain the herd and its beneficial grazing that reduced wildfire threats, the conservancy planned to import two pregnant cows.16

the Chincoteague ponies come in multiple color combinations

1. William Youatt, The Horse, Lea and Blanchard, 1843, p.26, https://books.google.com/books?id=Dljm2TlEg1cC; Jay F. Kirkpatrick, "Management of Wild Horses By Fertility Control: The Assateague Experience," Scientific Monograph NPS/NRASIS/NRSM-95/26, National Park Service, 1995, p.vii, p.5, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/science/26.pdf (last checked July 26, 2019)

2. "La Galga the Legendary Assateague Galleon," The Hidden Galleon, http://thehiddengalleon.com/; "Ponies," Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, US Fish and Wildlife Service, https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Chincoteague/wildlife_and_habitat/ponies.html; "Celebrating Our Past, Creating Our Future," Maryland Department of Natural Resources, https://dnr.maryland.gov/centennial/Pages/Centennial-Notes/AssateaguePonies.aspx; "Assateague's Wild Horses," Assateague Island National Seashore, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/asis/learn/nature/horses.htm; Edwin C. Bearss, "General Background Study and Historical Base Map: Assateague Island National Seashore Maryland - Virginia," National Park Service, December 18, 1968, p.3, p.20, http://npshistory.com/publications/asis/gbs-hbm.pdf; "Beloved Chincoteague ponies' mythical origins may be real," National Geographic, July 27, 2022, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/famous-chincoteague-ponies-may-actually-descend-from-a-spanish-shipwreck (last checked July 28, 2022)

3. "Interim Chincoteague Pony Management Plan," Appendix D in "Chincoteague and Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuges - Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement," US Fish and Wildlife Service, August 2015, pp.D-6 to D-10, https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Chincoteague/what_we_do/CCP.html; Edwin C. Bearss, "General Background Study and Historical Base Map: Assateague Island National Seashore Maryland - Virginia," National Park Service, December 18, 1968, p.12, http://npshistory.com/publications/asis/gbs-hbm.pdf (last checked July 26, 2019)

4. Howard Pyle, "Chincoteague," Scribner's Monthly, Volume 13 Issue 6 (April 1877), p.738, posted online by Cornell University Library, http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/s/scmo/ (last checked August 6, 2014)

5. Edwin C. Bearss, "General Background Study and Historical Base Map: Assateague Island National Seashore Maryland - Virginia," National Park Service, December 18, 1968, pp.22-23, http://npshistory.com/publications/asis/gbs-hbm.pdf (last checked April 5, 2020)

6. "Interim Chincoteague Pony Management Plan," Appendix D in "Chincoteague and Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuges - Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement," US Fish and Wildlife Service, August 2015, pp.D-10 to D-11, pp.D-14 to D-15, p.D-17, https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Chincoteague/what_we_do/CCP.html; "Chincoteague Pony Auction FAQ," Chincoteague.com, http://www.chincoteague.com/blog/?p=423; "DNA evidence may link Chincoteague pony origins to Spanish shipwreck," Washington Post, August 6, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2022/08/06/chincoteague-ponies-spanish-shipwreck-dna/; "Resource Brief - Horses," Assateague Island National Seashore, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/asis/learn/nature/resource-brief-horses.htm (last checked August 7, 2022)

7. "The True Story of Misty of Chincoteague, the Pony Who Stared Down a Devastating Nor'Easter," Smithsonian, October 16, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/real-misty-chincoteague-once-stared-down-barrel-storm-180970557/; "Misty of Chincoteague - Chick Lit Hero Horse," Roadside America, https://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/11838 (last checked July 26, 2019)

8. "'It's like the Super Bowl of horses' - Thousands watch - some arriving to secure spots as early as 3 a.m. - as Chincoteague ponies make 94th annual swim," The Virginian-Pilot, July 25, 2019, https://pilotonline.com/news/local/article_e2e5cd62-ae3b-11e9-9b06-0be8597c9813.html; "Interim Chincoteague Pony Management Plan," Appendix D in "Chincoteague and Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuges - Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement," US Fish and Wildlife Service, August 2015, pp.D-12 to D-13, pp.D-19 to D-20, https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Chincoteague/what_we_do/CCP.html (last checked July 26, 2019)

9. "Escorted by Saltwater Cowboys, the Chincoteague Ponies make their 94th annual swim across the channel from Assateague Island," Roadtrippers, July 24, 2019, https://roadtrippers.com/magazine/chincoteague-pony-swim/ (last checked July 26, 2019)

10. "Chincoteague Ponies," Chincoteague.com, http://www.chincoteague.com/ponies.html; "Chincoteague Pony Frequently Asked Questions," Chincoteague.com, http://www.chincoteague.com/articles/chincoteague-pony-faq.html; "The Wild Horses of Assateague Island," National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/asis/naturescience/upload/wildhorses-%20In%20Design.pdf; "Interim Chincoteague Pony Management Plan," Appendix D in "Chincoteague and Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuges - Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement," US Fish and Wildlife Service, August 2015, pp.D-8 to D-10, p.D-13, p.D-22, https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Chincoteague/what_we_do/CCP.html (last checked July 26, 2019)

11. "Census shows healthy wild herd at Assateague National Seashore," DelmarvaNOW, April 4, 2019, https://www.delmarvanow.com/story/news/local/maryland/2018/04/04/horse-population-ideal-assateague-island/485081002/; Jay F. Kirkpatrick, "Management of Wild Horses By Fertility Control: The Assateague Experience," Scientific Monagraph NPS/NRASIS/NRSM-95/26, National Park Service, 1995, p.6, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/science/26.pdf (last checked July 26, 2019)

12. "Scientists Stalk a Microscopic Monster Killing Chincoteague's Famous Ponies," WVTF, August 6, 2019, https://www.wvtf.org/post/scientists-stalk-microscopic-monster-killing-chincoteagues-famous-ponies; "Chincoteague pony 'swamp cancer' vaccine encouraging: Fire company," Salisbury Daily Times, January 22, 2020, https://www.delmarvanow.com/story/news/local/virginia/2020/01/22/chincoteague-pony-swamp-cancer-vaccine-results-encouraging-wild-horses/4532867002/; "At Chincoteague, Covid-19 Closes Spring Roundup to the Public," WVTF, April 15, 2020, https://www.wvtf.org/post/chincoteague-covid-19-closes-spring-roundup-public; "Chincoteague pony swim canceled for first time since WWII," Virginia Business, May 18, 2020, https://www.virginiabusiness.com/article/chincoteague-pony-swim-canceled-for-first-time-since-wwii/; "Chincoteague holds virtual pony auction as island adapts to historic pandemic," WTOP, July 29, 2020, https://wtop.com/entertainment/2020/07/chincoteague-island-holds-virtual-pony-auction-as-it-adapts-to-historic-pandemic/; "Pony auction shatters records with $380,000-plus spent in online version," Salisbury Daily Times, July 31, 2020, https://www.delmarvanow.com/story/news/local/virginia/2020/07/31/chincoteague-pony-auction-breaks-record-380-000-spent-online/5553368002/; "Chincoteague pony swim canceled for second year due to pandemic," Washington Post, April 26, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/chincoteague-pony-swim-canceled/2021/04/26/6dc5740a-a6b5-11eb-8d25-7b30e74923ea_story.html; "Virginia designation of state pony long overdue, says Chincoteague mayor," Virginia Mercury, February 20, 2023, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2023/02/20/virginia-designation-of-state-pony-long-overdue-says-chincoteague-mayor/; "Chincoteague Pony Auction Includes Two Record-Breaking Pony Prices," Eastern Shore Post?, August 4, 2022, https://easternshorepost.com/2022/08/04/chincoteague-pony-auction-includes-two-record-breaking-pony-prices/; "Bidding sets record at 99th Chincoteague Pony Auction," Eastern Shore Post, July 26, 2024, https://easternshorepost.com/2024/07/26/bidding-sets-record-at-99th-chincoteague-pony-auction/; "Chincoteague pony swim turns 100 amid big emotions and little horses," Washington Post, August 1, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2025/08/01/chincoteague-pony-swim-assateague/ (last checked August 1, 2025)

13. "Interim Chincoteague Pony Management Plan," Appendix D in "Chincoteague and Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuges - Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement," US Fish and Wildlife Service, August 2015, pp.D-1 to D-12, https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Chincoteague/what_we_do/CCP.html (last checked July 26, 2019)

14. "28 wild horses drowned off Outer Banks in 'mini tsunami' created by Hurricane Dorian," Charlotte Observer, September 24, 2019, https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/article235414287.html; "Cows swept out to sea by Hurricane Dorian are found months later – on the Outer Banks," The Charlotte Observer, November 12, 2019, https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/article237280754.html (last checked November 24, 2019)

15. "Feral Horses," Cumberland Island National Seashore, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/cuis/learn/nature/feral-horses.htm; "The Wild Horses Of Cumberland Island, GA," Wild Horse Islands, http://www.wildhorseislands.com/cumberlandislandhorsesga.html; "Feral horses may go on Cumberland Island," The Brunswick News, September 15, 2015, https://thebrunswicknews.com/news/local_news/feral-horses-may-go-on-cumberland-island/article_0406df03-77d2-53fe-8269-d6553d5b0c25.html (last checked March 24, 2020)

16. "The Uneasy Future of Catalina Island's Wild Bison," Smithsonian Magazine, September 22, 2022, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/uneasy-future-catalina-island-wild-bison-180980559/ (last checked August 28, 2022)

the cover of the 1951 yearbook for Chincoteague High School

Source: Internet Archive, 1951 yearbook for Chincoteague High School