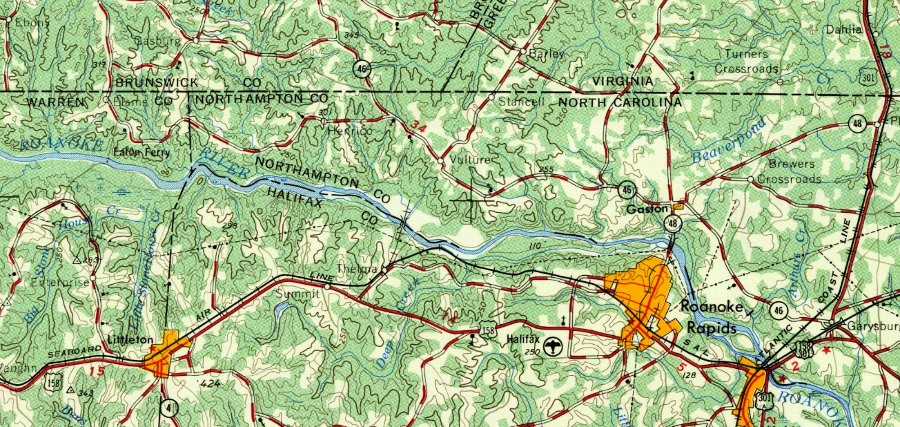

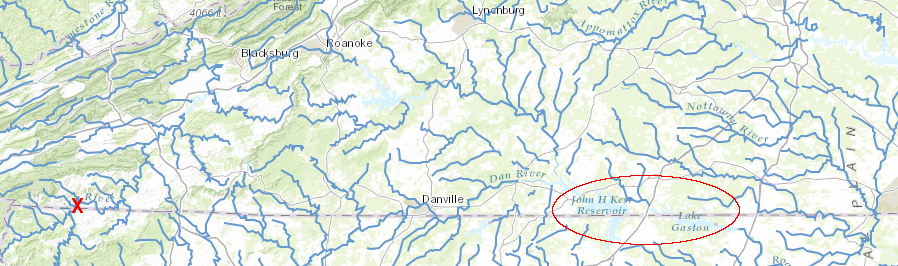

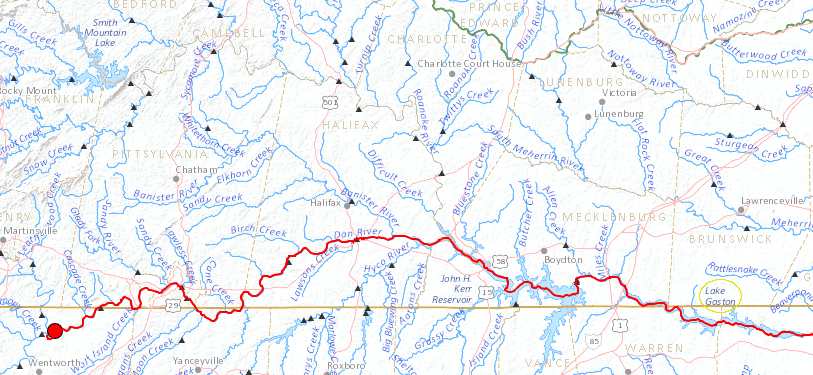

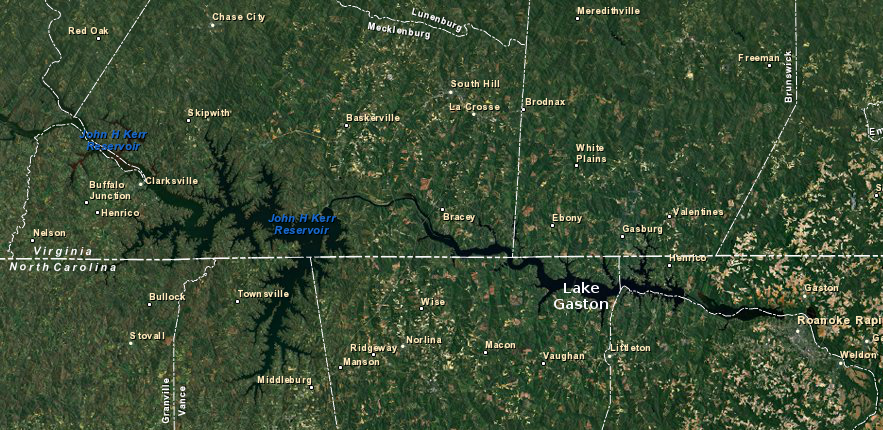

Lake Gaston is sandwiched between Roanoke Rapids Lake and Kerr Reservoir (Buggs Island Lake), 100 miles west of the resort area of Virginia Beach

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Lake Gaston is sandwiched between Roanoke Rapids Lake and Kerr Reservoir (Buggs Island Lake), 100 miles west of the resort area of Virginia Beach

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

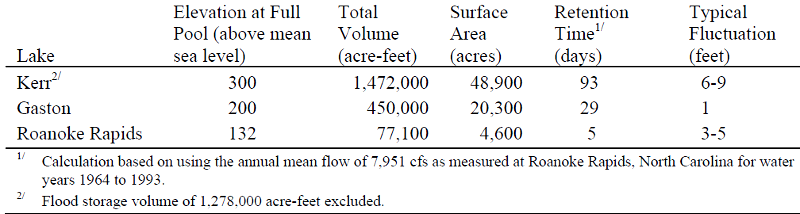

Lake Gaston is a 20,000-acre artificial lake, roughly 40% the size of Kerr Reservoir just upstream and 450% larger than Roanoke Rapids Lake downstream. Both reservoirs were formed by dams built on the Roanoke River. The Lake Gaston dam was built in 1963 by Virginia Power and Electric Company (now Dominion Virginia Power), just south of the Virginia/North Carolina border.

Kerr Reservoir (known in Virginia as Buggs Island Lake) was created by the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1952 for flood control and hydropower. Roanoke Rapids Lake was created by Dominion Power in 1955 to generate electricity.

In Virginia, Kerr Reservoir/Buggs Island Lake and Lake Gaston have replaced the free-flowing Roanoke River. There are two large artificial flatwater lakes in Mecklenburg, Brunswick, and Halifax counties that drown over 70 miles of the Roanoke River, plus Roanoke Rapids Lake in North Carolina.

Creation of the three lakes has changed the local economy, stimulating tourism and recreational second home development. Drivers on Route 58, in the traditional tobacco-growing area of Southside Virginia, now see pickup trucks pulling trailers with large yachts large enough for trips on the Atlantic Ocean.

The construction of Roanoke Rapids dam in 1955 was delayed until a Federal court ruled that the private utility company had the right to a permit to build a hydropower project. That decision came after the election of President Eisenhower in 1952 led to a change in Federal government policy, with a shift away from publicly-funded hydropower projects. Einsenhower's Secretary of the Interior, Douglas J. McKay, was labelled by opponents as "Giveaway Doug McKay."

The license to Dominion Power meant that the Federal government would not expand its projects downstream from Kerr Reservoir, and would not be the exclusive developer/operator of all hydropower dams on the Roanoke River.

in 1953, dams had not created Lake Gaston or Roanoke Rapids Lake yet on the Roanoke River

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk, Virginia 1:250,000 scale topographic map (1953)

The Corps of Engineers and Dominion Power synchronize operation of water releases from different dams. Dominion times generation of hydropower by its turbines at Gaston Dam with water releases at Kerr Dam. When the Corps of Engineers generates hydropower and releases water through the Kerr Dam, Dominion does not store the water and then

When water is released through the Kerr turbines, the same amount of water is allowed to flow through turbines downstream at Gaston Dam where Dominion generates electricity. Synchronizing releases minimizes the rise in the water level of Lake Gaston, with the height increase limited to just one foot except during floods:1

Lake Gaston was built originally as a single-use reservoir to generate hydropower. Unlike Kerr Reservoir/Buggs Island Lake, Lake Gaston was not designed to offer any flood control benefits, and new flatwater recreational opportunities were just a minor consideration. When the reservoir was built in 1963, neither Virginia nor North Carolina anticipated broadening the use of Lake Gaston to serve as a water supply... but the future shortage of drinking water in fast-growing Hampton Roads was already recognized as a problem. In the end, Lake Gaston became the solution to that problem.

Since 1998, Virginia Beach has pumped fresh drinking water from Lake Gaston to Hampton Roads residents. In a project that required 30 years of planning and lawsuits (with only a short portion of that time required for actual construction), Virginia Beach partnered with the City of Chesapeake to pipe water from Lake Gaston, out of the Roanoke River basin to customers in Hampton Roads.

When Virginia Beach and Chesapeake became independent cities in 1963, they expected rapid population growth. However, the new cities had limited access to the remaining surface water in southern Hampton Roads; the older cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth had previously developed the surface water sources.

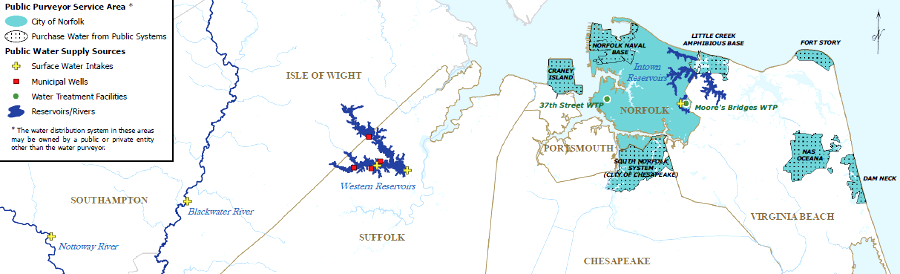

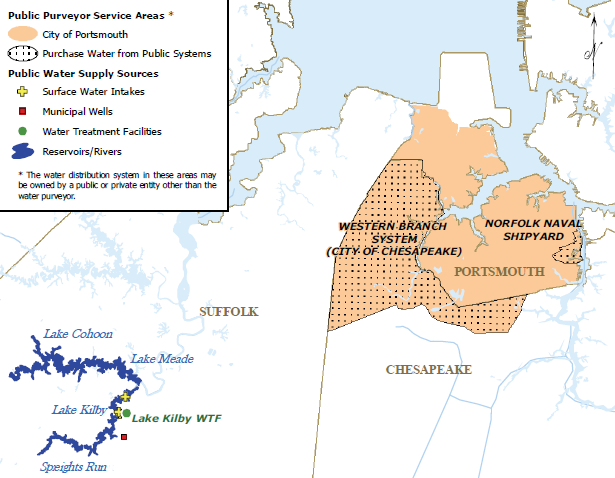

Portsmouth built Lakes Meade, Kilby, Cohoon, and Speights Run on the upper reaches of the Nansemond River, and drilled five deep wells to tap local groundwater. Norfolk's water sources include reservoirs in Virginia Beach, plus the Western Reservoirs of Lake Prince, Lake Burnt Mills, and Western Branch Reservoir in the City of Suffolk and Isle of Wight County, In addition, Norfolk pulls water from the Blackwater and Nottoway rivers and four deep wells located in Suffolk (which were drilled after a drought in the 1960's).2

water sources for City of Norfolk include interbasin transfers from Nottoway, Blackwater, and Nansemond rivers

Source: Norfolk Department of Utilities

Norfolk supplies drinking water to other community water systems and military bases in Hampton Roads

Source: Hampton Roads Regional Water Supply Plan (Map 1-13)

Portsmouth developed water sources on the Nansemond River - Lakes Meade, Kilby, Cohoon, and Speights Run - before the City of Suffolk

was incorporated and determined that it needed to utilize local water sources

Source: Hampton Roads Regional Water Supply Plan (Map 1-15)

One option for late-developing Virginia Beach was to tap into fresh water north of the James River. Newport News took the lead in trying to establish control over water resources on the Peninsula, seeking to acquire state and Federal permits to build the King William Reservoir. As planned Newport News would use an interbasin transfer pipeline to import water from the Mattaponi River into the James River watershed.

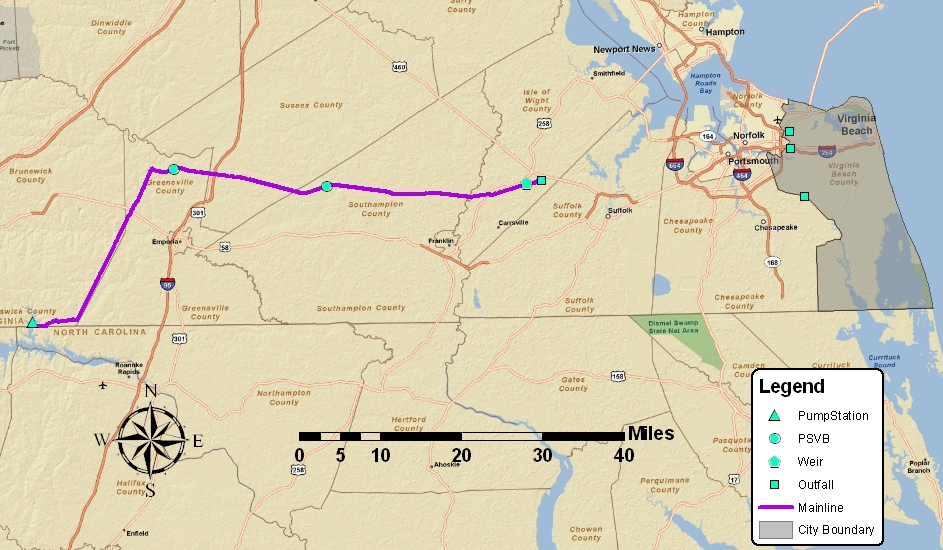

Virginia Beach and the City of Chesapeake, located south of the James River, chose a different source - they focused on getting 60 million gallons/day (MGD) from the Lake Gaston reservoir, already constructed 125 miles to the west. The City of Chesapeake took a 1/6th share of the project, for 10 million gallons/day.

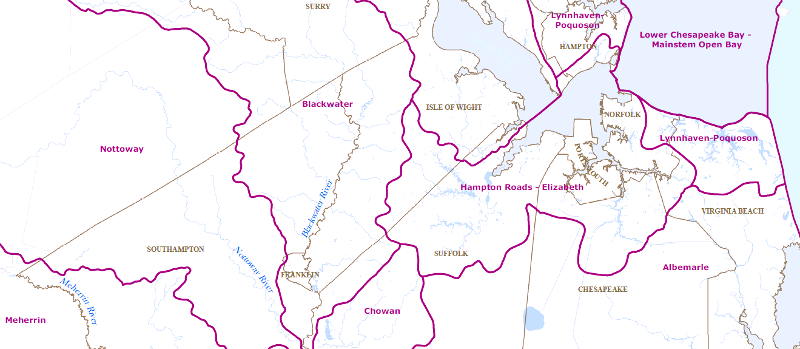

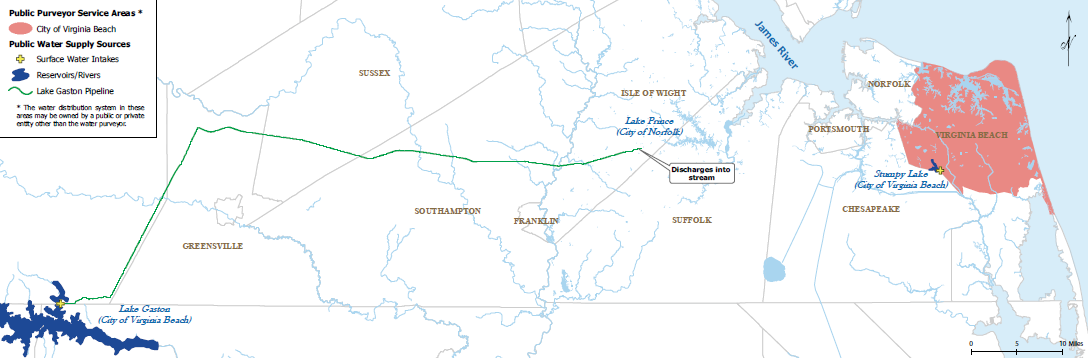

Virginia Beach ended up building the longest drinking straw in Virginia - a pipeline 76 miles long and 60 inches wide. It stretches from the Pea Creek intake on Lake Gaston, west of I-95 on the North Carolina border, crosses the Meherrin, Nottoway, and Blackwater rivers, and exits the Roanoke River basin entirely before reaching Ennis Pond in Isle of Wight County and then Lake Prince, a reservoir in the City of Suffolk. Additional local pipes connect the Norfolk water system and Virginia Beach, allowing tourists in oceanfront hotels on Atlantic Avenue in Virginia Beach to turn on their taps and get fresh water from the Roanoke River.

Sucking water from the Roanoke River to supply southern Hampton Roads, just before the river flows into North Carolina, was very controversial. Roughly 2/3 of the Roanoke River watershed is located in Virginia, so 2/3 of the water in the Roanoke River originates as rainfall in Virginia. At Lake Gaston, upstream from most tributaries in North Carolina, an even higher percentage is runoff from Virginia.

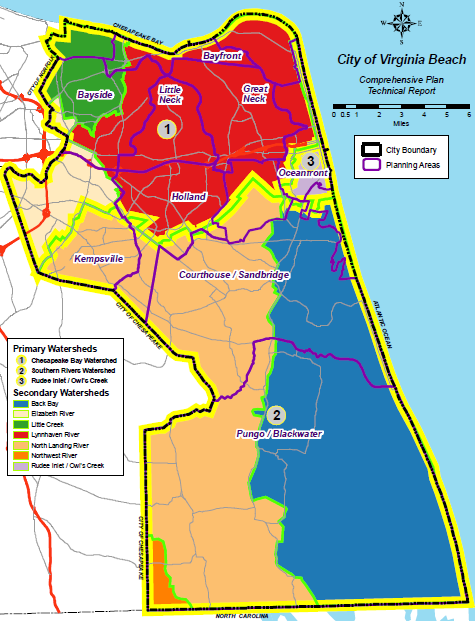

Hampton Roads watersheds

Source: Hampton Roads Regional Water Supply Plan (Map 3-2, Major Watersheds)

Still, North Carolina has consistently objected to diverting Roanoke River water to Virginia Beach. At one point, the North Carolina governor declared:3

Inter-basin diversion was not a new concept for North Carolina. As far back as 1925, the Eastern States Development Company had proposed to build a dam on the New River in Grayson County, Virginia and divert the river's water to the Fisher River (a tributary of the Yadkin River in North Carolina) to generate electricity. The diversion would have transferred water from the Gulf of Mexico watershed to the Atlantic Ocean watershed, and reduced the flow to the hydropower dams at Byllesby and Buck in Carroll County.

To protect its ability to use the full flow of the New River to generate electricity, the Appalachian Power Company objected to the diversion proposal. In its legal documents, Appalachian Power cited concerns regarding states rights and riparian rights. The project was not built, and no legal precedent was set.4

50 years before the Lake Gaston pipeline, a water diversion project to prevent North Carolina water from flowing into Virginia was proposed on the New River (red X)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Efforts by the North Carolina-Virginia Water Resources Management Committee to negotiate an agreement on the use of the Roanoke River started in 1978. In 1983, Virginia Beach stepped outside of the negotiation process and requested a permit from the Corps of Engineers to withdraw water from Lake Gaston. That triggered 20 more years of legal and political conflict, even after the pipeline started moving water from the Roanoke River watershed to the initial storage site in the Nansemond River watershed (and ultimately to Virginia Beach customers further east) in 1998.5

Negotiations almost resolved the dispute in 1995. A proposed interstate compact included a commitment by Virginia to widen highways in Hampton Roads that would increase tourism in the Outer Banks region of North Carolina. However, residents of the rural Virginia counties near Lake Gaston opposed the deal because they feared loss of "their water" and new environmental constraints designed to protect water quality in the reservoir. The settlement opportunity died when Governor Allen of Virginia refused to call a special meeting of the General Assembly, because Democrats who controlled the legislature would not limit the session to just the Lake Gaston issue and then adjourn.

The Virginia legislature was paralyzed by partisan bickering, but regional politics were also involved:6

route of Lake Gaston pipeline, crossing Meherrin River, Nottoway River and Blackwater River watershed divides

Source: Hampton Roads Regional Water Supply Plan, Map 1-18: City of Virginia Beach Sources and Service Area

The City of Norfolk processes the water for Chesapeake/Virginia Beach, but did not join the Lake Gaston project. Norfolk already had sufficient water supplied by the Blackwater and Nottoway Rivers, plus four deep wells located in Suffolk.

Norfolk stores and treats the raw water pumped from Lake Gaston, then sends drinking water to Virginia Beach and Chesapeake. The Lake Gaston project was sized large enough to eliminate Virginia Beach's dependency on Norfolk for water supply, and at one point Norfolk almost sabotaged the pipeline project by claiming it had surplus water that could meet most of the Virginia Beach needs. The two cities ended up with a integrated system that requires perpetual cooperation.7

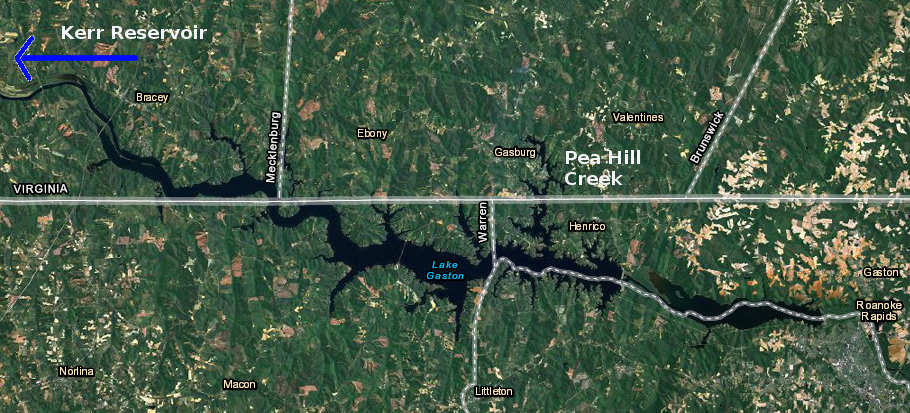

most of Lake Gaston is in North Carolina - but the arm where Pea Hill Creek was flooded extends into Virginia,

so the Virginia Beach pipeline intake was located north of the Virginia/North Carolina border

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service Wetlands Mapper

When the 50-year Federal license for the Gaston Dam was scheduled to expire in 2001, the state of North Carolina tried to force the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to block relicensing unless the interbasin transfer by Virginia Beach was ended. North Carolina claimed the decreased stream flow would affect downstream economic development potential and damage natural resources, especially striped bass spawning.

the Lake Gaston pipeline stops near Lake Prince, and Norfolk's water system then delivers treated drinking water to Virginia Beach and Chesapeake

Source: Virginia Beach Public Works Lake Gaston Water Supply Pipeline

North Carolina tried to use its authority under the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA) to block the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) from authorizing the pumping station on Pea Hill Creek. In the end, both FERC and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration in the Department of Commerce (NOAA is the Federal "umpire" that determines if projects are consistent with a state's coastal zone management plan) approved the pipeline project, just as the Corps of Engineers had done earlier. Virginia Beach was able to negotiate a settlement with various stakeholders, including Dominion Power and North Carolina, in order to obtain FERC re-licensing, with provisions for reduced water withdrawals during droughts, annual weed control on Lake Gaston, and continuation of recreation activities on the lake.8

Virginia Beach has noted that downstream of the Lake Gaston dam, flow in the Roanoke River through North Carolina could be reduced 1% (and up to 4% in a major drought) - but the withdrawals would not reduce the level of Lake Gaston itself, because the intake structure for the pipeline is near the downstream end of the reservoir after water has already flowed through the lake.

However, levels in Kerr Reservoir (also known as Buggs Island Lake) upstream of Lake Gaston could be lowered 2-4 inches. Virginia Beach acquired water rights in Kerr Reservoir from the Corps of Engineers, and the water supply for the pipeline withdrawals is captured and stored in Kerr Reservoir/Buggs Island Lake rather than Lake Gaston. The level of Kerr Reservoir/Buggs Island Lake is lowered slightly each day when the city's water is released into Lake Gaston as needed, and then pumped out of Lake Gaston to Virginia Beach.

physical characteristics of Kerr Reservoir, Lake Gaston and Roanoke Rapids Lake

Source: Dominion Virginia Power, Shoreline Management Plan For The Roanoke Rapids And Gaston Hydropower Project (Table 1-1)

During a drought, the Corps of Engineers will release water from Lake Kerr into the upper end of Lake Gaston. The City of Virginia Beach withdraws the water at the lower end of Lake Gaston at Pea Hill Creek, thus maintaining the level of Lake Gaston between elevations 199 to 200 feet while still extracting sufficient water for the urban customers.

Since Kerr Reservoir is primarily a flood control project where water level can range between elevations 293 and 320 feet, the environmental and economic impact of an additional drop of 2-4 inches to meet Virginia Beach needs was not considered significant enough to block the project. In contrast, the Roanoke Rapids project is managed to generate power at times of peak demand. That reservoir fluctuates between 127-132 feet, and the dam often releases only the minimum required flow on weekends (except during the sprint spawning season for striped bass.)9

Virginia Beach considered alternatives to the interbasin transfer from the Roanoke River. These included desalinating brackish or salty seawater, drilling local groundwater wells, recycling wastewater from local sewage plants, and building new impoundments on the Assamoosick Swamp or the Appomattox River. The top five options considered most closely were:10

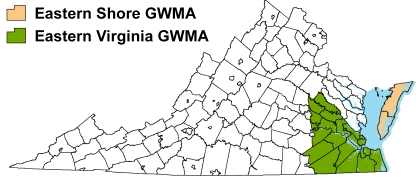

Drilling new wells was one obvious option. However, if the city pumped extra water from underground, the normal flow of rainwater to recharge the aquifers would be interrupted. Pulling massive amounts of water from the aquifers underground was expected to result in seawater intrusion, damaging private wells in the region as the saltwater replaced the freshwater underground:11

Ground Water Management Areas in Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Ground Water Withdrawal Permitting Program

The opportunity to extract more groundwater to increase the drinking water supply was limited in part because of the "bolide" (meteor/comet) that slammed into the eart's crust 35 million years ago. That impact shattered the bedrock and disrupted aquifers between Norfolk and the Eastern Shore, trapping a pool of super-salty water underground. Deep groundwater (greater than 300') near northern Hampton Roads requires expensive desalinization.

To meet the needs of its expanding population, the City of Suffolk built an "electrodialysis reversal" plant to desalinate brackish groundwater from the Middle Potomac Aquifer in 1990. In 1999, Chesapeake upgraded its Northwest River Water Treatment Plant to treat bracking groundwater from the same source and from the Northwest River. There was still plenty of water remaining in the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean for the cities of Virginia Beach and Chesapeake, but it was 25-35 parts/thousand (2.5-3.5%) salt, and desalinization costs increase dramatically as salinity increases.12

When the cities of Chesapeake and Virginia Beach committed to using the Roanoke River as their water source, the two Hampton Roads cities developed a permanent interest in the Roanoke River watershed upstream of Lake Gaston. In 2012-13, the owner of a rich uranium deposit at Coles Hill in Pittsylvania County, 190 miles to the west, proposed modifying state regulations to allow mining and milling of uranium ore.

The potential of uranium being processed along a tributary of the Roanoke River triggered alarm in Hampton Roads. The tourism industry could be affected by fears of "glow-in-the-dark" drinking water, even if there was no real possibility of radioactive contamination reaching customers in Oceanfront hotels.

Virginia Beach funded a study to identify impacts from a disastrous breach of a mine's containment system, perhaps in a rain event comparable to Hurricane Camille in 1969. The study concluded that Kerr Reservoir (Buggs Island Lake) would trap 90% of the uranium tailings, but the city might be forced to stop using water from Lake Gaston for 1-2 years.13

in 2014 a coal ash spill polluted the Dan River (a tributary of the Roanoke River) and Virginia Beach stopped pumping water from Lake Gaston

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas Streamer

In 2014, Virginia Beach was faced with a real threat from upstream contamination. A pipe broke underneath a pile of waste coal ash, stored at a former power plant on the Dan River near Eden, North Carolina. So much coal ash poured into the river that the Dan River turned gray in Dancville, and ash coated the Dan and Roanoke river bottoms for 70 miles downstream all the way to the Kerr Reservoir.

Within two days, Virginia Beach stopped pumping water from Lake Gaston. However, that measure was designed primarily to reassure the public that local drinking water would be unaffected by potentially toxic materials in the coal ash. The coal ash spill was comparable to just 4% of the volume used in the modeling of the potential uranium spill. The Virginia Beach Public Utilities Director stated that the city's water supply would not be affected for several months, if coal ash washed downstream in sufficient quantity to be dispersed throughout the lake and reach the city's pumping station in a protected cove. The city started pumping again from Lake Gaston at the end of May, four months after the spill.14

shallow aquifers at Virginia Beach

Source: USGS Fact Sheet 173-99, The Virginia Beach Shallow Ground-Water Study

Lake Gaston is on the Virginia/North Carolina border, formed by a dam in North Carolina that blocks the Roanoke River and backs up water across the state line

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service Wetlands Mapper

one-third of Virginia Beach is in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, and no watersheds in the city drain into the Roanoke River

Source: Watersheds in Virginia Beach