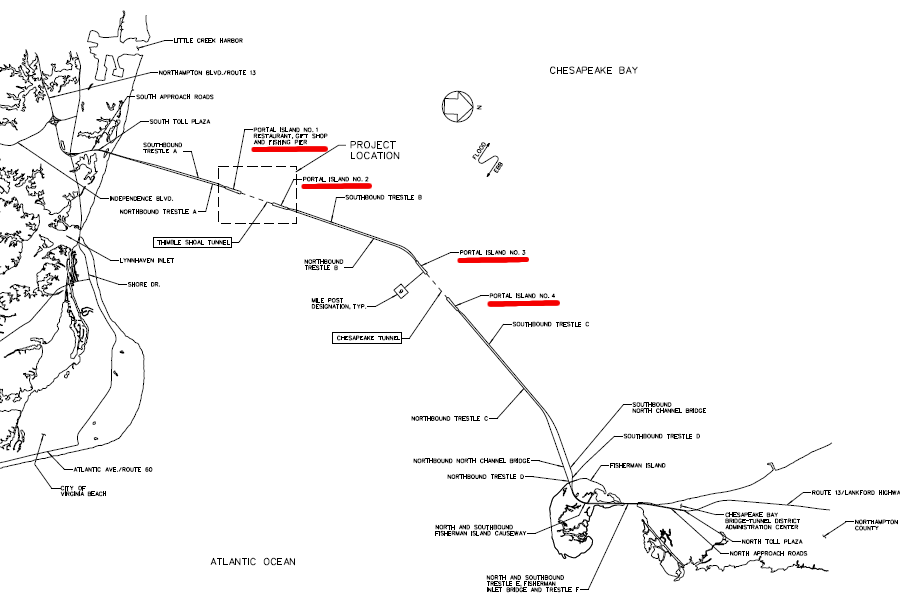

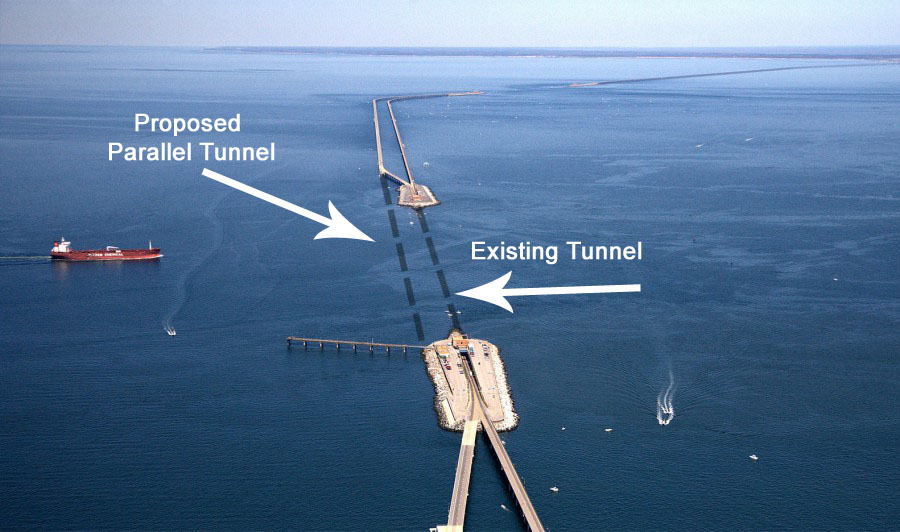

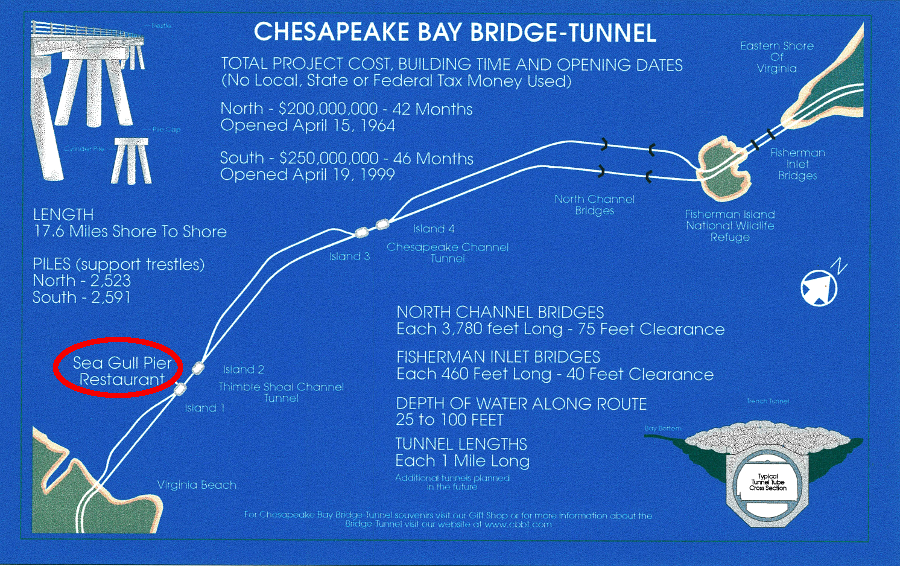

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel includes above-water bridge spans and underwater tunnels

Source: 2015 Governor's Transportation Conference, Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel - Project Overview

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel includes above-water bridge spans and underwater tunnels

Source: 2015 Governor's Transportation Conference, Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel - Project Overview

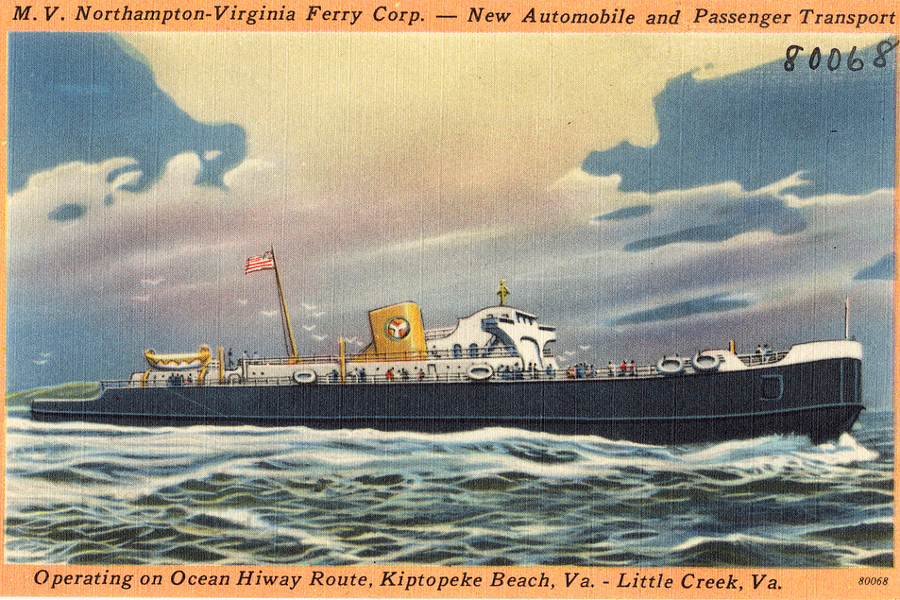

Steam-powered ferries provided a regular connection between Norfolk, Old Point Comfort, and Baltimore starting in 1817, but it was not until 1830 that ferries scheduled weekly service to the Eastern Shore. In 1884, after the Pennsylvania Railroad built a line down the Eastern Shore, daily ferry service connected Cape Charles to Norfolk and Old Point Comfort until the railroad limited its ferry service to transport of railroad cars in 1953.

a pre-World War II postcard shows the Virginia Ferry Corporation carrying passengers between Northampton and Princess Anne counties, prior to construction of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Boston Public Library, M. V. Northampton-Virginia Ferry Co. -- New automobile and passenger transport operating on ocean hiway route, Kiptopeke Beach, VA - Little Creek, VA

The first ferry designed to carry automobiles started service in 1933. The Virginia Ferry Corporation linked the Eastern Shore to the "mainland" from the 1930's to 1956.

migratory farm workers took the ferry from Norfolk to Cape Charles

Source: Library of Congress, Florida migratory agricultural workers at the Norfolk-Cape Charles Ferry. They are on their way to New Jersey and Migratory agricultural workers at the Little Creek end of the Norfolk-Cape Charles ferry. They are going to Bridgeville, Delaware to pick apples

(by Jack Delano, 1940)

Passengers and vehicles had to spend 90 minutes on a ferry to go across the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, from Cape Charles to Little Creek. The northern ferry landing at Cape Charles was moved to Kiptopeke in 1951. Nine concrete-hulled ships built during World War II were sunk to create a breakwater, limiting wave action which could affect ferry operations at the terminal.

surplus World War II ships were sunk off the Kiptopeke ferry landing to provide protection from waves

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Townsend, VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2019)

The concrete ships, "named after pioneers in the science and development of concrete," are now marketed as a tourist attraction to lure visitors to Kiptopeke State Park.1

the concrete ships are now just a tourist attraction, after the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel ended ferry operations in 1964

Source: Virginia State Parks, Photo contest GetOutdoors! Kiptopeke State Park

After World War II, increasing use of automobiles created a stronger demand for a faster crossing. In 1952, Maryland built its Chesapeake Bay Bridge near Annapolis to cross the Chesapeake Bay, with a four-mile span to Kent Island. In 1957, completion of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel demonstrated the potential for a bridge-tunnel combination to overcome the long distance between the Eastern Shore and Virginia Beach, without impeding ship traffic at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

The Virginia General Assembly created the Chesapeake Bay Ferry District in 1954. It purchased the Virginia Ferry Corporation and began operating the ferries in 1956, the same year the General Assembly authorized a bridge-tunnel facility to link the Eastern Shore to Hampton Roads.

The General Assembly renamed the "Chesapeake Bay Ferry District" and the "Chesapeake Bay Ferry Commission" in 1959, converting them into the "Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District" and the "Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission." The ferry service, using seven vessels, continued until the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel opened in 1964.

A ferry loaded with up to 60 cars took 90 minutes to go 18 miles at the mouth of the bay, with further delays during storms with strong winds and choppy waves.2

Since 1964, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel has carried US 13 between the Eastern Shore of Virginia and Hampton Roads. A variety of names were considered for the structure, including Virginia Capes Bridge-Tunnel and Virginia Capes Crossover. Names including "oceanway" and "seaway" were rejected out of concern that travelers might think a boat would be required.

The facility was officially renamed the Lucius J. Kellam, Jr. Bridge-Tunnel in 1987, honoring the local civic leader who is credited with making the bridge-tunnel become a reality. Kellam was the chair of the Chesapeake Bay Ferry Commission while it existed. He became the first chair of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Commission in 1959, and held that position until retiring in 1993. Despite the official name change, all signs and publications continue to refer to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel.3

The facility was officially renamed the Lucius J. Kellam, Jr. Bridge-Tunnel in 1987, honoring the local civic leader who is credited with making the bridge-tunnel become a reality. Kellam was the chair of the Chesapeake Bay Ferry Commission while it existed. He became the first chair of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Commission in 1959, and held that position until retiring in 1993. Despite the official name change, all signs and publications continue to refer to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel.3

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel is not the longest bridge in the world. That honor belongs to the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge, at over 102 miles long. It is the fourth longest bridge in the United States. The Lake Pontchartrain Causeway is the longest in the country, followed by two other bridges in Louisiana.

The Fehmarn Belt tunnel, connecting Denmark and Germany will be the world's longest underwater tunnel, if completed in 2029 as planned. The tunnel, now under construction, will be 11 miles long underneath a strait in the western part of the Baltic Sea. The world's first underwater tunnel was constructed in London between 1825-1843. The Thames Tunnel was initially used as a pedestrian walkway. It became a railway tunnel, and is still used for that purpose.4

The combination of bridges and tunnels that form the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel cross 17.6 miles of water from shore to shore, enabling over 3.5 million vehicles each year to cross from Northampton County to the City of Virginia Beach. Between the toll plazas on the north and south ends, the bridge-tunnel is 20 miles long. Counting the approach roads, the facility is 23 miles long. Each of the underwater tunnels is over one mile long, and the entire project is a major engineering achievement.

to limit erosion, massive chunks of granite armor the shorelines of the four artificial islands on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel

The 858 bridge spans of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel are 30 feet high above the water, to avoid wave action and to allow small boats to pass. The spans are supported by 4,805 concrete pilings driven into the sediments at the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay. The longest piling was driven 172' deep. The pile driver was a special machine known as Big D, with steel legs that could be jacked up by compressed air. During the Ash Wednesday storm in 1962, the Bid D could not be raised higher than the waves. The legs snapped, causing extensive damage.

After driving the piles, they were cut at the top to ensure a flat and consistent surface. Three piles were held together at the top by a concrete cap, creating a "bent" to support the bridge decks installed at the end of the construction process. Cutting the pilings to the correct height and installing the horizontal "bent" was done by a unique machine known as the Two-Headed Monster, built solely for that purpose.

Bedrock at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay is over 6,000 feet deep, so the pilings are supported solely by accumulated sediments. Test drillings identified where the sand and clay were most compact, most capable of keeping the pilings in place. The curves in the bridge were designed to take advantage of the best soil conditions.5

curving south from Fisherman's Island, where the North Channel Bridge offers an alternative for small ships to avoid the Chesapeake Channel

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Photo Gallery

All of the precast concrete pilings and other materials were manufactured at the new Bayshore Concrete Products plant at Cape Charles. It was established initially for the project, and continued in business producing concrete materials for other major projects until closing in 2018. Had the company won contracts to supply concrete for the expansion of the Thimble Shoal tunnel, it might have stayed in business even longer.

Direct access to a barge dock enabled it to win contracts along the East Coast, including delivery of concrete products in New York for the new Tappan Zee Bridge, the raising of the Bayonne Bridge, and revising Terminal B at LaGuardia Airport. However, it was not successful in winning a contract to supply concrete products to the second tubes of the tunnels for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel and Bayshore Concrete Products then closed down. Coastal Precast Systems, which won the contract, was located in the City of Chesapeake. It bought the Cape Charles facility and re-opened in 2019.6

Bayshore Concrete Products built a plant on 90 acres at the town of Cape Charles in 1960, to manufacture precast concrete pilings and other materials for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The bottom of the Chesapeake Bay is owned by the state of Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Commission had to pay the Virginia Marine Resources Commission for the use of the state-controlled submerged land.

over 4,800 concrete pilings support the twin spans of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District, Annual Report to His Excellency, the Governor for the Year ending December 31, 2014 (p.25)

The two tunnels, each over one mile long, were essential to the project.

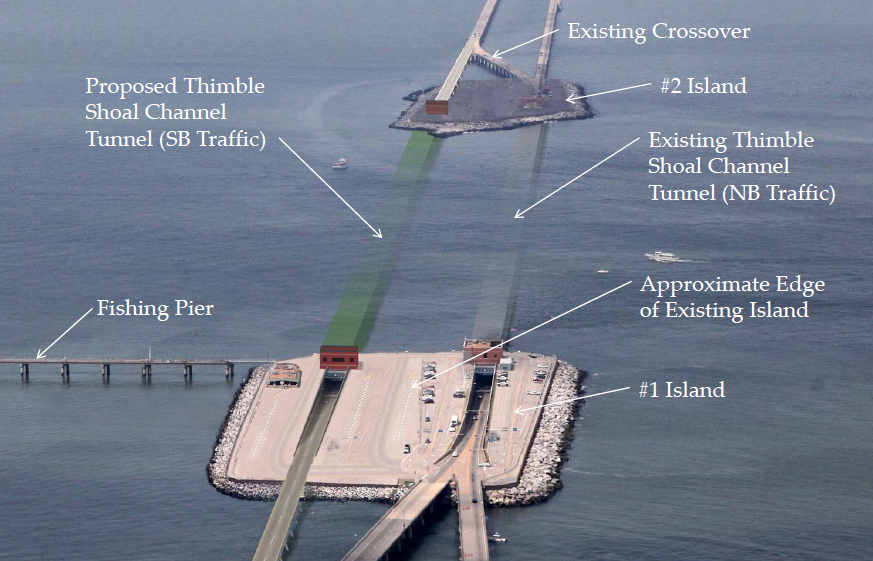

the Thimble Shoal tunnel is anchored by Island 1 on the south and Island 2 on the north

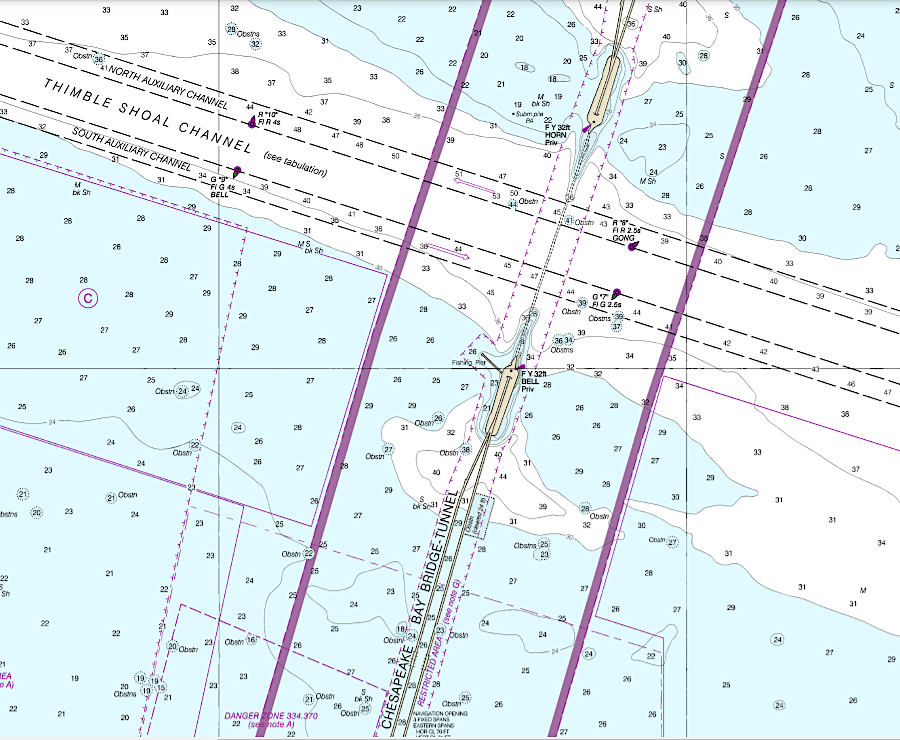

The Thimble Shoal tunnel crosses the old channel of the James River. The US Navy relied upon that deep channel for its warships to access the Atlantic Ocean, and objected to any bridge across the channel. Any barrier to ship traffic in Thimble Shoal Channel would seriously limit the Navy's capabilities on the East Coast.

In warfare, an enemy might destroy the bridge and block the Thimble Shoal channel. That could bottle up the Navy's ships inside Chesapeake Bay and prevent ships in the Atlantic Ocean from reaching the massive naval base at Norfolk.

The Hudson River was not so essential, so the US Navy did not object to construction of the George Washington Bridge. The Holland Tunnel was built underneath the Hudson River in the 1920's not to maintain national security, but because there was no room on Manhattan Island for a long ramp.

The risk of a collapsed bridge blocking the shipping channel was well known from history, including the potential of intentional sabotage. The Rock Island Bridge, completed in 1856, was the first railroad bridge across the Mississippi River. Just 15 days after completion, the steamboat Effie Afton passed through the open drawbridge portion but then lost power. The steamboat crashed into the bridge and caught fire, and then the railroad bridge burned completely.

Investigation into the event could not determine why the Effie Afton was traveling so far upriver from its normal routes. Mississippi River steamboat interests had been strongly opposed to construction of the Rock Island Bridge. There was suspicion that the collision was intentional, and that the steamboat had been carrying highly flammable cargo intended to catch the railroad bridge on fire. The Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company trial to determine if the railroad should pay damages for creating currents which caused the collision ended with a hung jury. That trial helped establish the reputation of the railroad's defense lawyer, Abraham Lincoln.

More recent proof that the risk was not just hypothetical came in March 2024. A container ship struck a pier supporting the I-695 (Francis Scott Key) bridge over the Patapsco River, at the entrance to the Baltimore harbor. The bridge collapsed, creating an impassable barrier to shipping at one of the major East Coast ports. Between 1960 to 2015, ship or barge collisions knocked down 35 bridges worldwide. Half of those bridge collapses occurred in the United States.

building a tunnel beneath Thimble Shoal, eliminating the potential threat of a bridge blocking ship traffic, satisfied the objections of the US Navy

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Photo Gallery

a ship collision in 2024 caused the collapse of the I-695 (Francis Scott Key) bridge, blocking traffic into the Baltimore harbor and demonstrating why the US Navy insisted on tunnels at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay

Source: National Transportation Safety Board, NTSB B-Roll - Aerial Imagery of Francis Scott Key Bridge and Cargo Ship Dali

North of the Thimble Shoal Channel, the Chesapeake Tunnel crosses the Chesapeake Channel, the old route of the Susquehanna River before sea level live after the Last Glacial Maximum created the Chesapeake Bay. Ships going to Baltimore used that route, and Maryland officials insisted upon a tunnel to ensure that channel would always be open to maritime traffic. Even further north near Fisherman's Island, the bridge is elevated to allow small vessels to pass underneath. That enables them to avoid going the extra distance to the Chesapeake Channel, and reduces the traffic congestion there.

The tractor-trailers crossing the elevated bridge sections inevitably encounter the gulls, other seabirds, and even peregrine falcons that constantly fly around the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. No technique has been developed yet to keep the birds from flying near the deck of the bridge, though waving banners and even walls have been considered. It is common to see bird carcasses on the bridge-tunnel, victims of high-speed collisions; thousands of birds die annually. One observer noted:7

high bridges over the North Channel of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel allow boats to travel underneath the spans without going south to the Chesapeake Channel

Source: presentation by Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District to Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization, Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel (June 19, 2014)

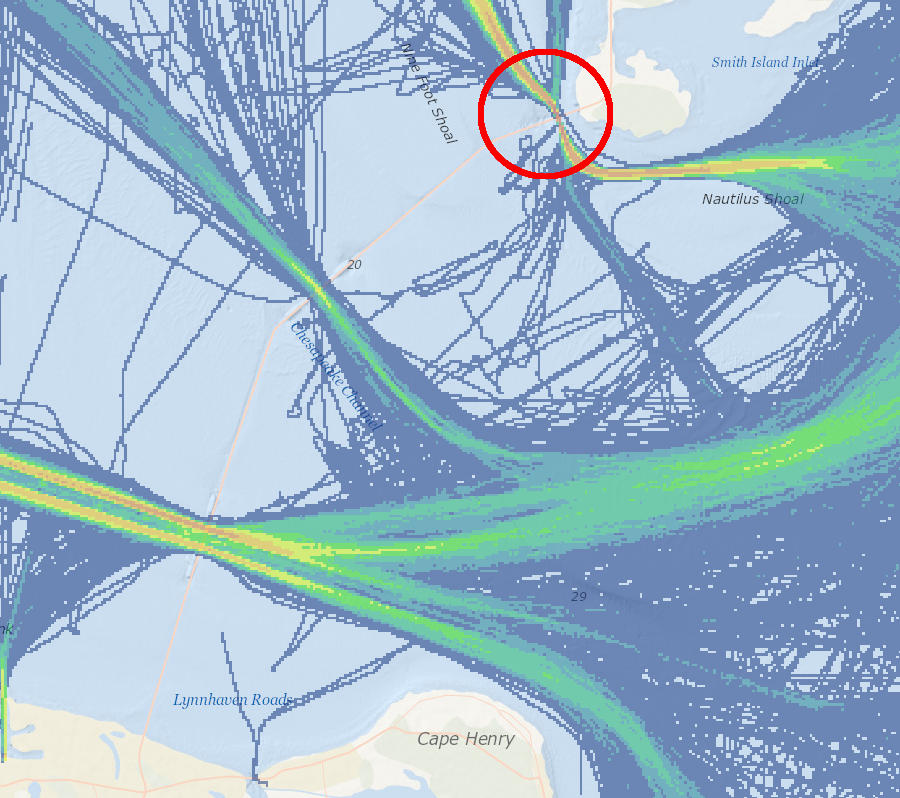

fishing boats utilize the North Channel of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, as well as the channels above the two tunnels

Source: Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal

Tunnel sections were prefabricated in Orange, Texas as 300-foot long, 35-foot in diameter steel tubes. For each tunnel, 37 sections were required. The ends were sealed so the tubes would float, then they were barged to Norfolk. Two of the airtight cylinders broke free from the tugs in the Gulf of Mexico. Both were recovered, though one had washed up on a Texas beach first.

At Norfolk, a two-foot-thick concrete shell was added before the sections were towed to the construction site and lowered into a trench previously excavated in the bay sediments. Once in place, tube sections were welded together and the connections were sealed with a coating of concrete, before the waterproof caps on the ends were removed. The final roadway inside the tube is 24-feet wide, plus a sidewalk less than 3-feet wide on one side.

The tunnels connect to the bridge spans at four artificial islands, at either end of the Thimble Shoal Channel and the Chesapeake Channel. Massive granite boulders, each weighing between 2-4 tons, were brought by rail from the Kenbridge granite quarry in Lunenburg County. The boulders were barged into the bay, then dropped to the bottom to form a ring larger than four football fields. Sand and gravel was pumped into the interior of the ring, and then another layer of boulders was added to raise the height of the column. At the surface, enough boulders were used to create a protective rip-rap that blocked erosion from even hurricane-induced waves.8

Source: An Engineering Marvel in the Making

Funding the bridge-tunnel required the General Assembly to change its traditional approach for funding highways. The Commonwealth of Virginia had followed a "pay as you go" approach since passage of the 1932 Byrd Road Act, but starting in 1956 substantial Federal funding to construct new highways became available. Local leaders on the Eastern Shore and in South Hampton Roads recognized that they would not obtain funding from the state or Federal sources soon, and obtained the state legislature's permission to sell bonds to finance the bridge-tunnel project.

The General Assembly chartered a political subdivision (separate from cities/counties), the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District. It is managed by the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission, an 11-member commission appointed by the governor to represent eight local jurisdictions and the state. Two members are from Accomack County, two members from Northampton County, and one member each from Virginia Beach, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Chesapeake, Hampton, and Newport News. The governor also appoints one member to represent the state.

The district includes two members from the Peninsula cities of Newport News and Hampton, showing how the bridge-tunnel was expected to have region-wide economic and transportation impacts. Only four of the 11 members on the commission come from the Eastern Shore counties, Accomack and Northampton.

six other local jurisdictions and the state have voting members on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission, but Accomack and Northampton counties each have two representatives

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

As a political subdivision of the state, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District operates its own police force. In 2015 the officers issued over 4,000 traffic citations, including nearly 30 for Driving Under the Influence (DUI). All fines are paid into the state's Literary Fund, so there is no incentive for the district to operate a "speed trap." Traffic accidents average around 20/year.9

The commission was authorized to issue revenue bonds, which had to be repaid through tolls. Selling the bonds raised the initial money required to pay contractors to build and manage the new structure.

Because the bonds were not backed by a guarantee of funding through local property taxes or the general revenue of the state, the "full faith and credit" of Virginia was not put at risk. No state bailout was promised if the toll revenues were inadequate to repay interest/principal to the investors who purchased the bonds. The Commonwealth of Virginia provided no construction money to build the initial bridge-tunnel or to expand it, though the state does provide urban street funding now for maintaining the transportation facility.

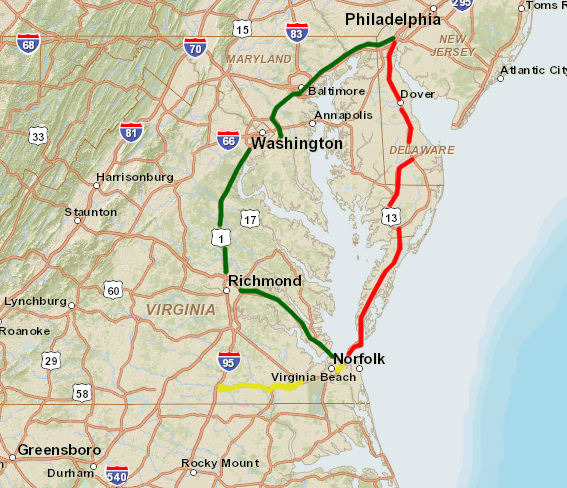

The new bridge-tunnel provided a 90-mile shortcut for traffic headed north to Delaware and New York compared to I-95, which was also completed in the mid-1960's. Despite the shorter distance, the better-quality road and faster speeds on the interstate attracted most of the traffic. Commercial businesses on the Eastern Shore, including poultry plants, continued to ship primarily to customers towards the north rather than use the bridge-tunnel to ship to customers in Hamton Roads or to export products through the Virginia Port Authority terminals.10

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel reduces the distance from Norfolk-Philadelphia by 90 miles - but traffic coming up I-95 rarely diverts to Route 13

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

The lack of business affected the financing for the project. The bridge-tunnel commission sold $200 million in revenue bonds in 1960, with half of the total assigned to Series C. In 1970, the commission defaulted on the "Chessie C" series, because traffic projections had been too optimistic and toll revenues were inadequate to pay bondholders what they had been promised. In 1985, revenues had increased, past due interest was paid, and the commission's credit rating improved.11

revenues have exceeded operating expenses since the 1964 opening, but repayment of the Class C bonds was delayed in 1970 because revenues were below estimates

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District, Annual Report to His Excellency, the Governor for the Year ending December 31, 2014 (p.2)

In 2012, the Fitch bond rating agency affirmed the A- rating for roughly half of the outstanding bridge-tunnel bonds, and noted:12

four islands were constructed at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay to anchor the two tunnels

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Geotechnical Baseline Report, Chesapeake Bay Bridge - Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel (Figure 1)

The initial bridge-tunnel was a two-lane highway. Capacity on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel is being increased through major projects every 20 or so years as old bonds are retired. According to the original 1956 enabling legislation, when all bonds have been paid the bridge-tunnel will become a toll-free road in the state highway system - which will occur 100 years after initial authorization, if current plans are fully implemented.

Island One under construction, on south side of Thimble Shoal channel

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Geotechnical Baseline Report, Chesapeake Bay Bridge - Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel (Figure 7A)

The General Assembly approved the first phase of expansion in 1990, and parallel bridge spans were constructed in 1995-99. The tunnels over Thimble Shoal and Chesapeake channels were not expanded to four lanes because building parallel tunnels is far more expensive than building parallel bridges.

![]()

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel first added parallel spans, but more-expensive parallel tunnels were delayed until a second Thimble Shoal tunnel was started in 2017

Source: 2015 Governor's Transportation Conference, Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel - Project Overview

With no delays, vehicles drive across the current Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel in 21 minutes. During scheduled closures of traffic lanes for routine maintenance, that time can increase to 28 minutes. Closures caused by the need to use both lanes of a tunnel for oversized loads, or from accidents within the tunnels, increase the average crossing time to 33 minutes.13

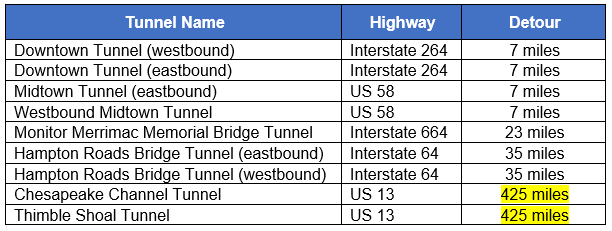

a closure of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel creates the longest detour of any tunnel in Hampton Roads

Source: Federal Highway Administration, National Tunnel Inventory

Separating the traffic on the bridge spans in 1999 reduced the potential for head-on accidents. Drivers afraid to cross the facility can make arrangements for workers at the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel to drive their vehicles. During 2015, over 400 drivers with phobias/fears took advantage of this service.

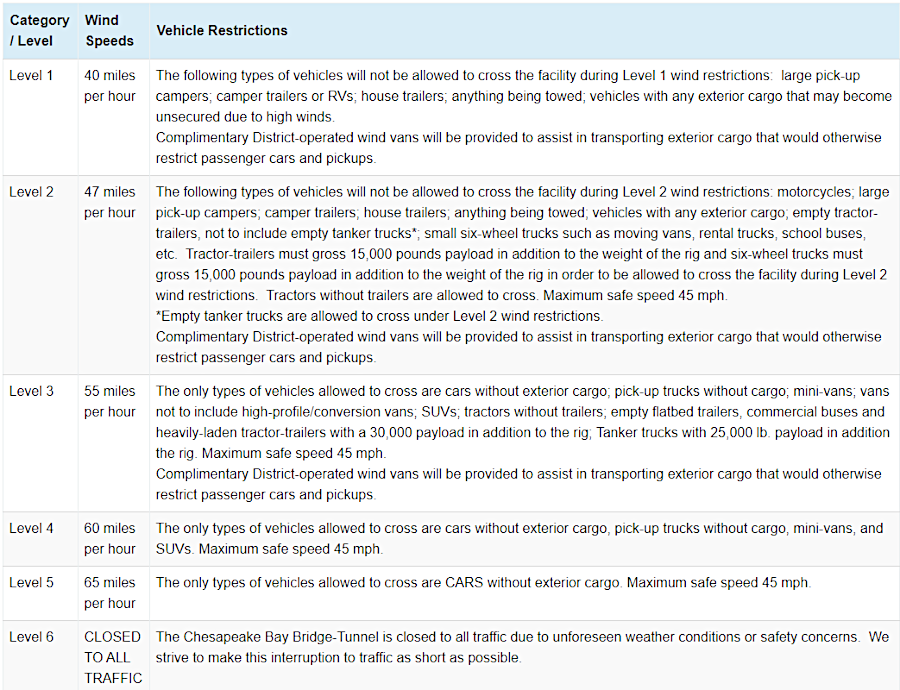

The funnel between Eastern Shore and Virginia Beach can create strong winds that are a safety risk on the bridge-tunnel. There are six levels of restrictions, starting with limits on campers and towed vehicles when wind speeds reach 40 miles per hour. The bridge-tunnel is closed to all tractor trailers when speeds reach 60 miles/hour. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District uses different criteria than the Virginia Department of Transportation, which closes most of its bridges when sustained winds reach 45 miles per hour.

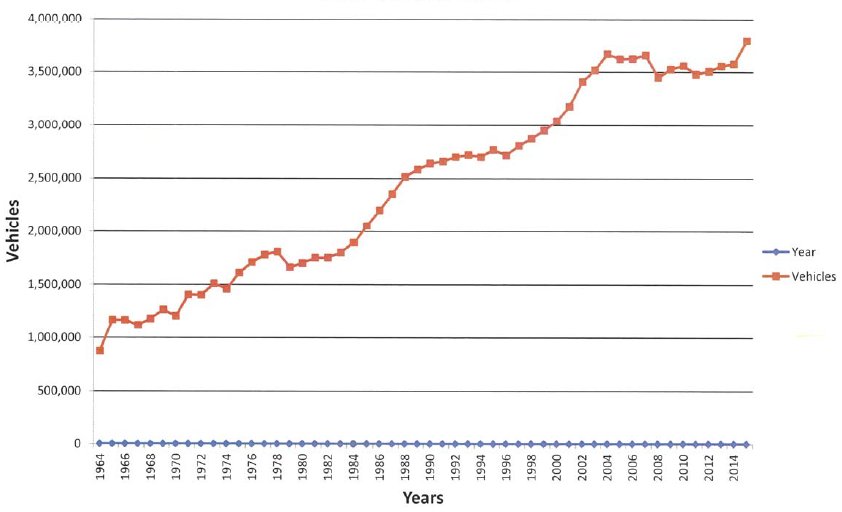

About 4 million vehicles use the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel each year, Half of them are from Virginia, and half from out-of-state.

In 2014, 355,000 trucks crossed the bridge-tunnel. Truckers with empty trailers or light loads, taking US 13 to avoid congested I-95, are especially at risk when wind gusts catch them broadside. A southbound tractor-trailer collided with a van in 2018 during a heavy rainstorm, then broke through the guardrail and sank into the Chesapeake Bay. The van stayed on the bridge and its occupants survived, but the crash was fatal for those in the tractor-trailer.

A 2017 crash of an empty tractor-trailer killed the driver and led to the first lawsuit claiming the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel was liable. The widow claimed the truck should not have been allowed on the bridge-tunnel because a 47mph gust of wind struck the toll booth as the truck passed through. Lawyers for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel claimed that the average wind speed was used to implement closures rather than intermittent gusts. The average was calculated with the use of four sensors on the bridge.

Before the empty tractor-trailer was lifted up by a 50mph gust and blown through the guardrail, 80 trucks had been stopped on the Eastern Shore until a storm had passed. Then Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel staff determined that the winds had dropped sufficiently to allow travel, but only 79 trucks made the crossing successfully that day. The lawsuit was dismissed four years later, with the judge ruling that the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel had followed its policy and was thus protected by sovereign immunity.

In accidents where vehicles go through the guardrail and into the Chesapeake Bay, recovering the wreckage and bodies may take days. In 2018 a tractor-trailer and van collided during a heavy rainstorm, and the truck went overboard. The wreckage was recovered the next day, along with the body of the passenger. The driver's body was recovered two days after the accident, floating eight miles off Fisherman's Island.

In December 2020, a box truck crashed through the guardrails on the northbound bridge. The truck floated briefly after hitting the water, and the driver disappeared after being spotted floating westward away from the bridge. The body washed up on a beach in Cape Hatteras National Seashore, 100 miles to the south, in April 2021.

A trucker's description of the experience of driving above the water was succinct:14

between 1964-2020, wind was the primary reason that 16 vehicles crashed through the guardrails

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District, Wind Restrictions

A driver died in 2023 after a tire on his 18-wheel truck hit the curb and blew out; the truck then plowed through the guardrail and sank into the Chesapeake Bay. It was the 17th over-the-side accident since 1984, and the 13th truck to fall off the bridge. In one accident, lightning is thought to have struck a tractor-trailer.

By July 2023, a total of 20 people had died in over-the-side accidents. In some cases, cars flipped overtop the guardrail after collisions. Two truckers have been rescued alive after plunging into the water.

The guardrails are TL (Test Level)-3 barriers according to Manual for Assessing Safety Hardware (MASH) standards. Three hollow aluminum pipe rails have aluminum support posts every eight feet. Those aluminum guardrails are effective at keeping cars and pickups going 62mph or less on the road, but are unable to block a heavy truck from breaking through even when struck at an angle.

Concrete jersey barriers on the edges of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel and Monitor-Merrimac Bridge-Tunnel are TL-5 barriers. In most situations, they can redirect a tractor-trailer going no more than 50mph back onto the road. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel spans were not designed to carry the extra weight of concrete barriers, so the light aluminum guardrails can not be upgraded.15

The tunnels remain as two-lane bottlenecks. They will be expanded in two phases, starting with a project to add a second two-lane tunnel for the underwater crossing at Thimble Shoal. The commission plans to build a parallel tunnel crossing the Chesapeake Channel in 25-35 years. Each new tunnel will require widening the current islands to accommodate a second portal.16

since 1964, the number of vehicles crossing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel annually has increased nearly 400%

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District, Annual Report to His Excellency, the Governor for the Year ending December 31, 2015 (p.2)

In 2013, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission committed to the Thimble Shoal Parallel Tunnel Project. The Parallel Crossing Consortium (PC2) then submitted an unsolicited proposal under the state's Public Private Transportation Act (PPTA) for preconstruction and design services. That proposal was not accepted, and the commission instead invited competitive bids for a design-build contract.

All of the original price proposals exceeded the cost estimate, so the scope of the project was revised and a second round of bidding proceeded in 2016. The final award, for a cost estimate of $756 million, was $260 million lower than earlier bids.

The major reduction in cost was accomplished by eliminating much of the Thimble Shoal island expansion. That eliminated a planned restaurant, retail shop and 200 additional parking spots. The fishing pier on the island will be re-opened, once construction is completed.

the fishing pier at Island 1 (Thimble Shoal) was designed so it could be re-opened after the island is widened for a parallel tunnel

The construction project for the parallel tunnel at Thimble Shoal was scheduled initially to be completed in five years, in 2022. That was almost six decades after the bridge-tunnel was first opened.

All three competitive bids were based on using a tunnel boring machine, rather than digging a trench and sinking sections of the new tube into it. All 10 previous tunnels in Hampton Roads, including the additional Midtown Tunnel tube that was completed in 2016, had been constructed by the "cut and fill" approach. Contractors had built sections of the tunnel tube offsite, then floated those sections to the site and sunk them into a prepared trench.

The tunnel boring machine was scheduled to excavate 50 feet per day. That pace required a year for the machine to excavate and install tube walls from the southern island to the northern edge of the channel. Tunneling creates fewer environmental impacts by not disturbing the sediments on the bottom of the channel, and by not disrupting submerged wildlife migrations or shipping traffic on the surface.

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel chose to construct the second tunnel at Thimble Shoal with a tunnel boring machine

Source: 2015 Governor's Transportation Conference, Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel - Project Overview

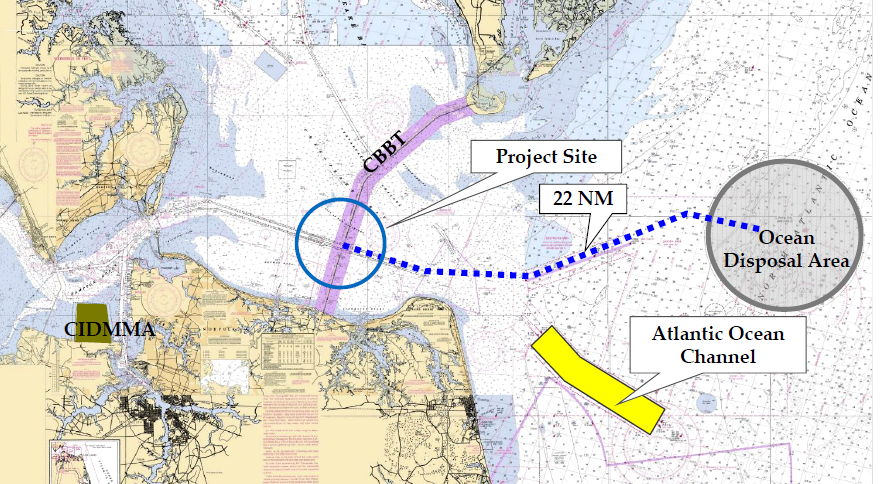

Because the boring machine uses various chemicals to lubricate the blades and move the slurry to the back of the machine, at least some of the excavated sediments will be contaminated with petroleum compounds called "Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons." Such sediments must be placed in a lined landfill, where the compounds can not leach into a groundwater aquifer. Non-contaminated sediments will be barged to the Norfolk Ocean Disposal Site. The Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area (CIDMMA) is closer, but it does not accept sediments dredged from the Chesapeake Bay.17

material not contaminated with Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons will be barged 22 nautical miles (NM) to the Norfolk Ocean Disposal Site

Source: 2015 Governor's Transportation Conference, Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel - Project Overview

The boring machine, built in Germany, was named "Chessie" after a contest among local sixth-graders. That name refers to a mythical creature, similar to the Loch Ness monster, that has been reported in multiple but unverified sightings in the Chesapeake Bay. The second choice for the name was "Bessy the Boring Bufflehead."18

the name "Chessie" was chosen in 2018, while the tunnel boring machine (TBM) was still under construction in Germany

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, TBM Naming Contest

When the new tunnel is completed, both lanes of the existing tunnel will be used to carry northbound traffic headed to the Eastern Shore. The new tunnel at Thimble Shoal will add two more lanes, and the new tunnel will carry all southbound traffic headed to Virginia Beach.

the tunnel boring machine (TBM) Chessie was shipped in pieces from Germany, then assembled at the expanded southern island so it could start digging

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, 19

the second tunnel will cross underneath the southern, Thimble Shoal channel

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Project Description

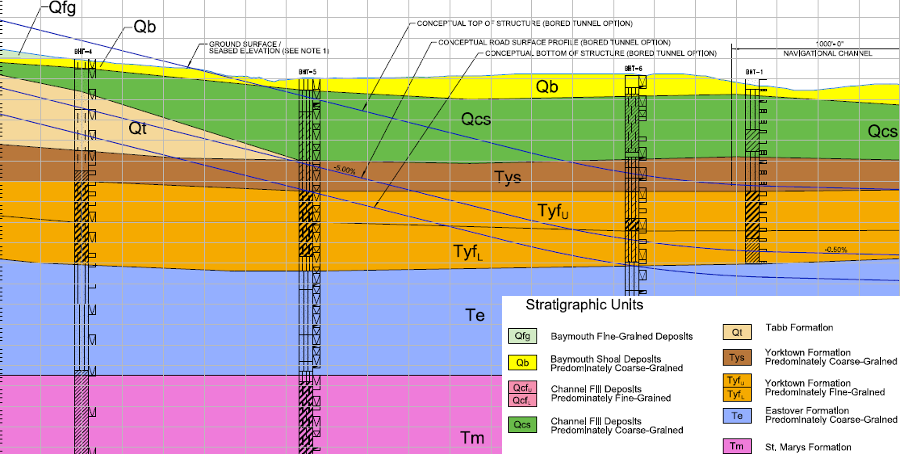

boring a tunnel required identifying characteristics of different sedimentary formations underneath the Chesapeake Bay

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Geotechnical Baseline Report, Chesapeake Bay Bridge - Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel (Figure 3C)

The new tunnel will be bored to allow dredging of a future channel 70' deep. That exceeds the depth of the 1964 tunnel, which was placed to accommodate a channel that might be dredged to 55 feet. The chief engineer of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel recommended in 2000 that designers plan for a 68-foot deep channel to be authorized in the future, beyond the current 50-foot depth and the authorized deepening to 55 feet.

The decision to use boring machines to excavate the sediments with an underground rotating cutting head rather than dredging a trench and sinking pre-made tubes, made the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel the third bored tunnel in the United States. The two previous bored tunnels were constructed in Miami and Seattle. Boring technology was also chosen for expansion of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, making it the fourth bored tunnel in the country.

The tunnel boring machine uses blades at the head to cut into the sediments and create a hole, which is then lined with nine large concrete rings and a tenth "key" ring to form the new tube.

the concrete rings to be installed by the tunnel boring machine were manufactured in the City of Chesapeake

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel - A Project Update

Excavated sediments are moved as a slurry via conveyor belt to the back of the boring machine and hauled away. The blades are lubricated with petroleum-based additives. If they contaminate the excavated material with over 50 milligrams of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH) per kilogram of soil, then the material must be transported to a lined landfill. The cheaper alternative, depositing contaminated material at an ocean dumping site or in an unlined sand pit onshore, is not environmentally acceptable.20

Few container ships are expected to need a depth greater than 55 feet in the future, but coal exporters from Norfolk could use bigger ships that require a deeper channel. Coal is heavier than the cargo in the containers, so ships carrying coal from Norfolk and Newport News sink lower into the water and require a deeper channel.

The 50-foot deep Chesapeake Channel is not used by ships carry heavy loads of coal from Norfolk to Europe. The most-heavily loaded ships are carrying containers, going to and from Baltimore located 175 miles further north. The expense of deepening the channel beyond 50' through the Chesapeake Bay to Baltimore would exceed the benefits, so there is no justification for the future parallel tunnel in the Chesapeake Channel to be installed any deeper than the 50" of the current tunnel.

The final design of the Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel will allow deepening the shipping channel below the currently-authorized 55-foot depth by up to 15 more feet:21

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District highlighted the tunnel expansion project in its 2014 annual report

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District, Annual Report to His Excellency, the Governor for the Year ending December 31, 2014

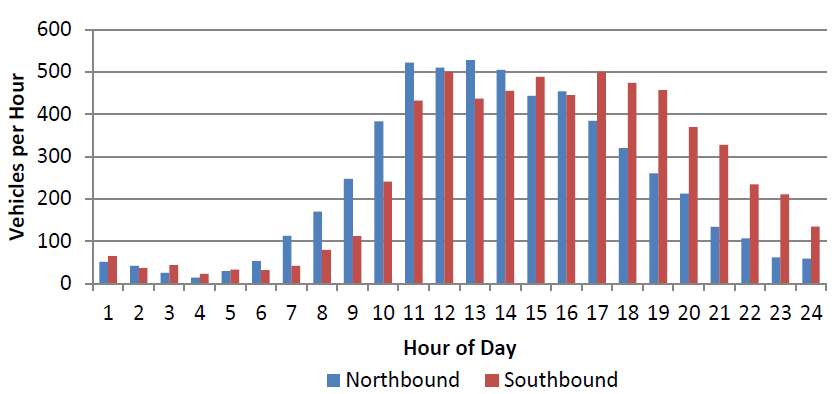

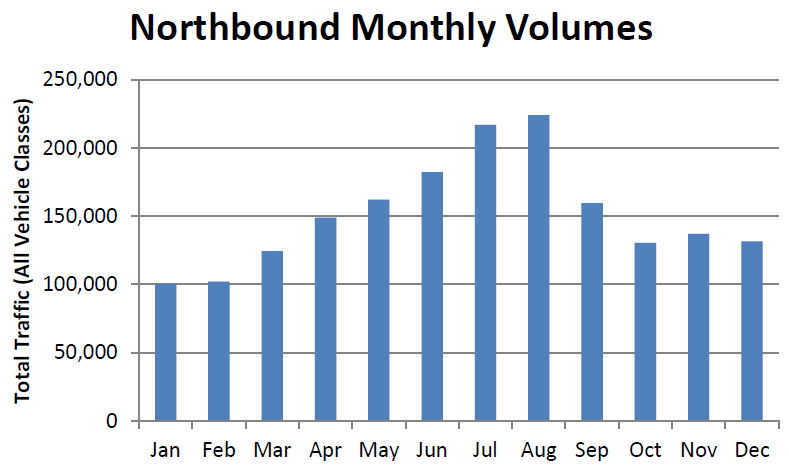

Traffic across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel is seasonal. The annual average is 11,000 cars per day, but in summer the demand peaks to 25,000 cars per day.

Even without the new tunnels, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel still has greater capacity than demand during most hours. Traffic normally flows freely at the designated speed limit. There is not a commuter rush-hour traffic jam where the four-lane bridges constrict into the two-lane tunnels under the Chesapeake Channel (the old path of the Susquehanna River) and the Thimble Shoal Channel (the old path of the James River), but there are occasional delays around noon. Once volume exceeds 1,100 vehicles per hour, the merge required to pass through the two-lane tunnels causes some delay.

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel crosses two ancient river channels

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bathymetric Data Viewer

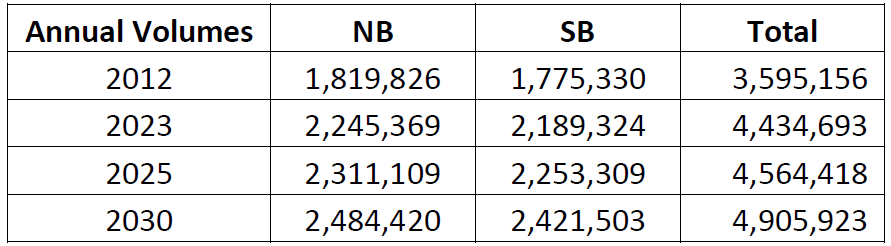

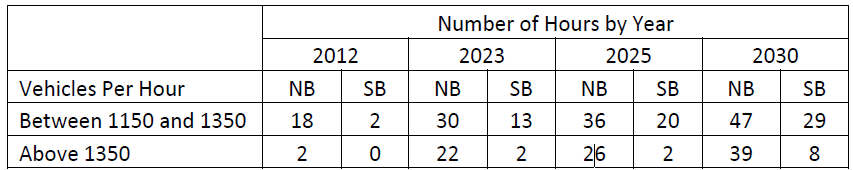

In 2012, the maximum traffic volume on the bridge-tunnel was 1,411 vehicles per hour. Consultants predicted a 1.7% per year increase in traffic annually until 2030, though estimates ranged from 0.9% to 2.1% annual growth.22

a projected a 37% increase in traffic crossing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel between 2012-2030 helped justify selling bonds to add a new tunnel at Thimble Shoal

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Chesapeake

Bay Bridge and Tunnel - Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel Environmental Assessment (p.22)

Building a new tunnel was justified in part by the expected growth in traffic, in part to allow complete closure of tunnels for maintenance, and in part to ensure continued operations in case of disaster. A floodgate did not close at Portsmouth's Midtown Tunnel in 2003 during Hurricane Isabel, and that flooded tunnel was closed for weeks. Single tunnels are single points of potential failure

In 2018, traffic in both directions on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel was limited for 17 hours, with a complete blockage for 10 hours. A truck carrying heavy equipment that exceeded the 13' 6" height limit entered the Thimble Shoal tunnel. The equipment, an 11-ton vibrating hammer needed for construction of the Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel Project, struck the ceiling of the tunnel and then fell into the roadway.

The too-high load was not caught by normal checks because the hammer was already on the bridge-tunnel when it was loaded onto the truck. Some drivers were trapped on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel in a seven-mile backup; some experienced delays that lasted over five hours.23

Adding two more lanes at Thimble Shoal will reduce merge-related delays for northbound traffic, but will not improve the flow for traffic coming south from the Eastern Shore. Southbound traffic must first pass through the tunnel at the Chesapeake Channel. Traffic exiting the Chesapeake Channel Tunnel and proceeding south to the Thimble Shoal Tunnel will already be constrained to 1,100 vehicles per hour. The increased capacity for southbound traffic flow at Thimble Shoal tunnel will be realized only after the second tunnel is built to cross the Chesapeake Channel.

hourly volumes of traffic on a typical off-peak day in 2012

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Chesapeake

Bay Bridge and Tunnel - Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel Environmental Assessment (p.6)

hourly volumes of traffic on a typical holiday weekend in 2012 show a peak earlier in the day, compared to a typical off-peak day

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Chesapeake

Bay Bridge and Tunnel - Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel Environmental Assessment (p.6)

traffic crossing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel peaks in the summer vacation season

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Chesapeake

Bay Bridge and Tunnel - Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel Environmental Assessment (p.4)

In 2012, the two-lane bottleneck at Thimble Shoal Tunnel caused a delay for less than 3% of the traffic headed northbound on the bridge-tunnel. Without a second parallel tunnel, by 2030 nearly 7% of the northbound traffic would have to slow down below the speed limit.

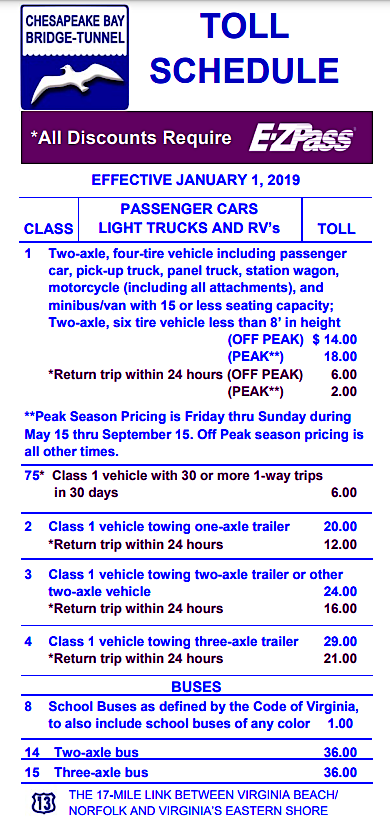

In addition, once traffic reaches 1,350 vehicles per hour another delay is caused by the maximum capacity to move cars through the toll plaza just south of the Thimble Shoal Tunnel. 55% of vehicles at peak times use E-Z Pass to speed through the toll plaza, in contrast to the daily average is just 38% E-Z Pass users.24

delays at the toll plazas occur when traffic reaches 1,350 vehicles per hour, despite the E-Z Pass lanes

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District, Annual Report to His Excellency, the Governor for the Year ending December 31, 2014

traffic will be delayed at the toll plaza to cross the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel for only a few hours per year, primarily between 11:50am-1:50pm

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Chesapeake

Bay Bridge and Tunnel - Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel Environmental Assessment (p.18)

Drivers on congested I-64 near Newport News or I-95 north of Richmond might envy expanding the capacity of a road experiencing so few delays, but upgrading those interstates could not be funded by revenue from the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. Tolls from bridge-tunnel users are dedicated to maintaining and expanding the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel.

The new tunnel project was added to the Hampton Roads 2034 Long-Range Transportation Plan and the Hampton Roads 2012-2015 Transportation Improvement Program in 2014 by the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District self-finances its construction and maintenance costs using tolls paid by drivers, so building the Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel did not require approval by the Commonwealth Transportation Board.

The project was not ranked in the Smart Scale analysis conducted by the Virginia Department of Transportation. The new tunnel was not funded by the state's share of the gas tax or other revenues dedicated to transportation improvements in Virginia.

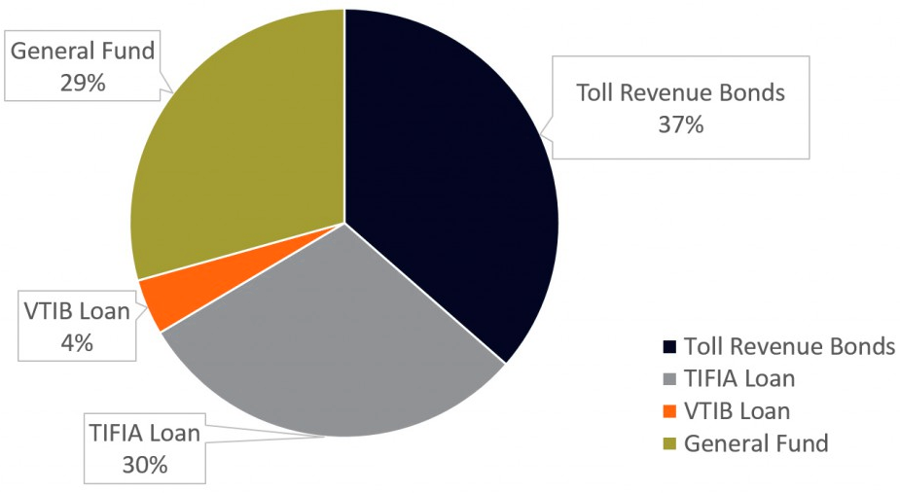

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District's financial reserves were not adequate to fund the new tunnel; the district had to borrow money. To finance construction of the new tunnel across Thimble Shoal, the district issued bonds for $756 million in 2016.

The district also borrowed from the Virginia Transportation Infrastructure Bank and obtained a Federal Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) loan. They offered lower interest rates than what was available from bonds sold to the private sector. Repayment of the loans and bonds depends upon projected increases in toll revenue.25

funding for the Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel comes from various sources, but ultimately all revenue to pay for the project is generated by tolls from vehicles crossing the structure

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel Project, Project Description

The commission had planned to start construction in 2021, but accelerated the date due to low interest rates. The commission decided to increase tolls 10% starting in 2014, with future 10% increases every five years until 2054, to generate the revenue required to pay off the new bonds sold to fund construction. Tolls increased 10% in 2019 and another 10% in 2024.

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel includes two underwater tunnels, one under the Thimble Shoal channel for shipping traffic to reach Hampton Roads and one under the Chesapeake Channel for traffic to Baltimore

Source: Joint Legislative Audit And Review Commission, The Future Of The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel (Figure 3)

Reflecting the financial constraints imposed by funding construction through revenue bonds, which are repaid by tolls on users of the bridge-tunnel, the construction of parallel tunnels underneath the Chesapeake Channel (north of the Thimble Shoal Channel) was not planned until 2040.26

The planned opening of the new tunnel below the Thimble Shoal Channel quickly fell two years behind schedule, and the completion date was pushed back to 2024. A subcontractor was fired for non-performance, and the rip-rap around the southern island was thicker and deeper than expected.

Construction of the tunnel under the Thimble Shoal Channel started with widening the south island so the Tunnel Boring Machine named "Chessie" could excavate through soft soil. Expansion of the south island at Thimble Shoal required construction of a coffer dam, in order to protect the island from erosion when the granite boulders were moved out of the way.

The contractor planned to drive steel pilings for the coffer dam straight through the rip-rap, but pushing steel through the granite boulders turned out to be harder than expected. Only one or two piles could be driven each day. Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel officials interpreted the construction contract to say the extra costs would have to be absorbed by the contractors.

In 2022, the original completion date, a new completion target of 2027 was announced. The first boring by the tunneling machine was not anticipated to begin until 2023.27

building parallel tunnels will require widening the existing islands

Source: 2015 Governor's Transportation Conference, Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel - Project Overview

starting construction on the parallel tunnel at Thimble Shoal Channel

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel (January 18, 2022 Facebook post)

In May 2023, the tunnel boring machine had moved 700' along its planned 5,700' route when it ran into an old ship anchor. At that location the tunnel was below 50 feet of water and another 20 feet of sediments. The tungsten carbide blades on the cutting head of "Chessie" were not designed to excavate through metal, and the shallow depth in the sedimentary layers limited options for moving the anchor out of the way.

"Chessie" the boring machine was not restarted for nearly a year. The solution required a eight-month delay in the project and the completion date was shifted again to August 2027, nearly five years after the initial optimistic estimate.

The soft sediments had to be strengthened enough for the tunnel boring machine to carve through them without a major water leak. Raising the air pressure in front of the machine helped to hold the water back as grout was pumped into the sediments. As described by a Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Authority official:28

In addition to building parallel tunnels at the Chesapeake Channel, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel could be expanded to build a link to the Peninsula at Hampton. That theoretical construction option will remain just theory, because there is not enough traffic to justify the cost.

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel finances its construction through tolls of drivers who use the road, not through taxes on all residents in the state. An extension to the Peninsula might spur economic development on the Eastern Shore, but users of the road would bear the costs through increased tolls to finance additional construction. Increased demand for land on the Eastern Shore might provide windfall profits for property owners on the Eastern Shore, but the people receiving the benefits (landowners) would be separate from the people paying the costs (drivers paying higher tolls).

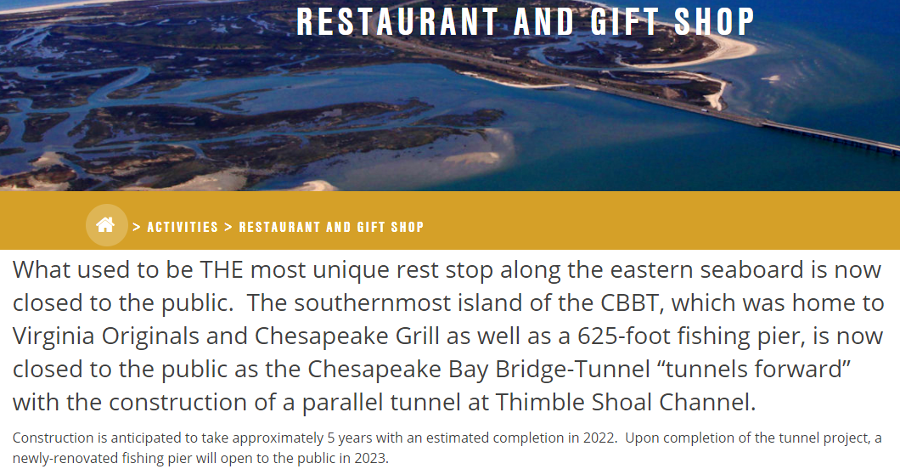

The assessment of costs vs. benefits also shaped the 2017 decision to close the Chesapeake Grill restaurant and Virginia Originals gift shop on Sea Gull Island, the southern base for the Trimble Shoal tunnel also known as "Island One" and as "One Island in the Bay." It would have cost an additional $200 million to build space for a replacement facility as part of the parallel tunnel.

An official with the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel said bluntly about financing a tourist stop in the middle of the Chesapeake Bay:29

when they closed in 2017, the restaurant on Sea Gull Island was known as the Chesapeake Grill and the gift shop was called Virginia Originals

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Facts

the Virginia Originals gift shop on One Island in the Bay offered a unique location for buying Virginia-made products

Source: Virginia Originals & Chesapeake Grill One Island in the Bay

the restaurant, souvenir shop, and visitor overlook on Island 1 closed on October 1, 2017 (click on images for larger versions)

after losing its location on One Island, Virginia Originals opened a small gift shop within the North Toll Plaza Rest Area and Welcome Center

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Restaurant and Gift Shop

Bridge-tunnel managers have adjusted toll rates, and even created a discount program for local residents.

In 2001, the roundtrip price was dropped from $20 to $14 (later increased to $18) if the return trip was completed within 24 hours. During the May 15-September 15 "Peak Season," costs were increased for trips made on Friday thru Sunday.

In 2013, a Discount 30/30 Toll Rate was created. After a customer made 30 trips (i.e., 15 roundtrips) in a one-month period, remaining trips for that month cost only $5 each way. By 2022, the discounted price was $6 per trip:230

tolls are discounted for off-peak use and quick round trip crossings

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Toll Rate Schdule

![]()

the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel connected the Eastern Shore to Hampton Roads in 1964

Source: 2015 Governor's Transportation Conference, Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Parallel Thimble Shoal Tunnel - Project Overview

the trust design used for the North Channel bridge (northbound, on left), indicates it was constructed before the parallel southbound span

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Photo Gallery

the Thimble Shoal Channel passes between the two islands created for the southern tunnel

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Chart 12254 (Chesapeake Bay - Cape Henry to Thimble Shoal Light)

Big D on the north, driving piles to support the future trestles of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel (March 9, 2023 Facebook post)