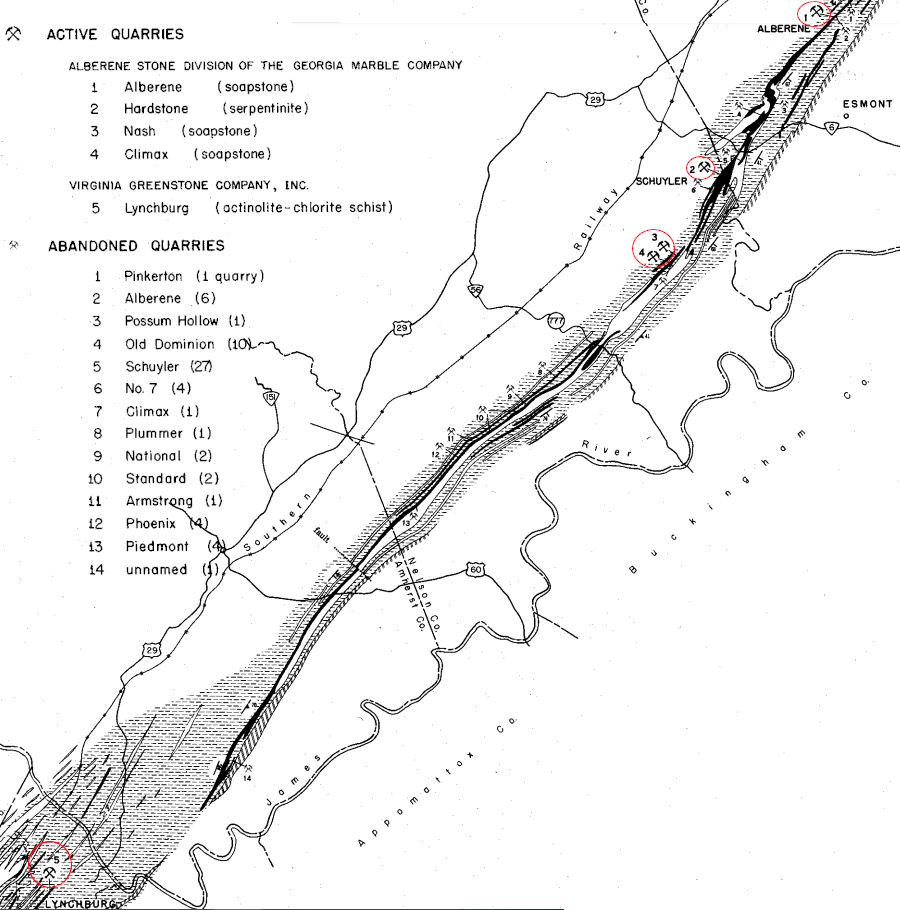

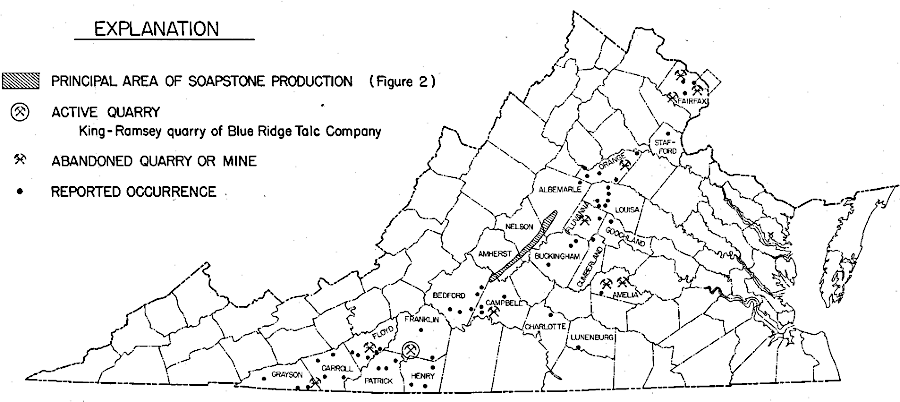

in 1961, five quarries were still producing soapstone that was carved into slabs

Source: Virginia Minerals, Talc, Soapstone, and Related Stone Deposits of Virginia (Figure 2)

in 1961, five quarries were still producing soapstone that was carved into slabs

Source: Virginia Minerals, Talc, Soapstone, and Related Stone Deposits of Virginia (Figure 2)

Soapstone is a metamorphic rock formed primarily from the mineral talc, which is magnesium silicate or Mg3Si4O10(OH)2. Talc is also known as steatite and serpentinite>

Talc is soft and "greasy/soapy" to the feel because it has weak molecular bonds between sheets of the mineral. Talc is the softest mineral on the Mohs Hardness Scale and is assigned a hardness of just 1. Other minerals mixed in with the talc make soapstone hard enough to carve.

The soapstone in Virginia originated nearly 500 million years ago. As island arcs and finally Africa collided with the North American plate, slices of seafloor ("ophiolite" fragments) were caught up with the marine sediments and continental "chunks" of terranes accreted onto Virginia's edge of the Laurentian tectonic plate.

During the Tectonic Orogeny about 460 million years ago, slices of ultrabasic rock were thrust from the bottom of the Iapetus Ocean seafloor onto the edge of the Norh American Plate. The ophiolite fragments were metamorphosed as the crust was squeezed onto the edge of the plate. When the Taconic Orogeny ended, there were pods of soapstone surrounded by other metamorphic layers, emplaced on the western edge of the terranes near the Grenville-age rock now exposed as the Blue Ridge.

Soapstone pods once buried deep during the accretion of terranes has been exposed now on the surface by erosion. Ophiolite fragments are visible now around Baltimore, in Fairfax County and in a mile-long, 30-mile wide zone of soapstone in the Blue Ridge:1

Different soapstone deposits were created as different terranes were pressed against the edge of the North American Plate. The Albemarle-Nelson Belt of soapstone stretching from Bedford to Madison counties is, geologically, placed in the Lynchburg Group. Quarries in Pittsylvania, Franklin, and Campbell counties were in the Smith River Terrane and the Alligator Back Formation. Amelia County deposits were in the Goochland terrane, while soapstone in Fluvanna, Orange, Louisa, Stafford, and Fairfax counties were in the Western Potomac terrane.2

A publication describing soapstone production in 1908 noted:3

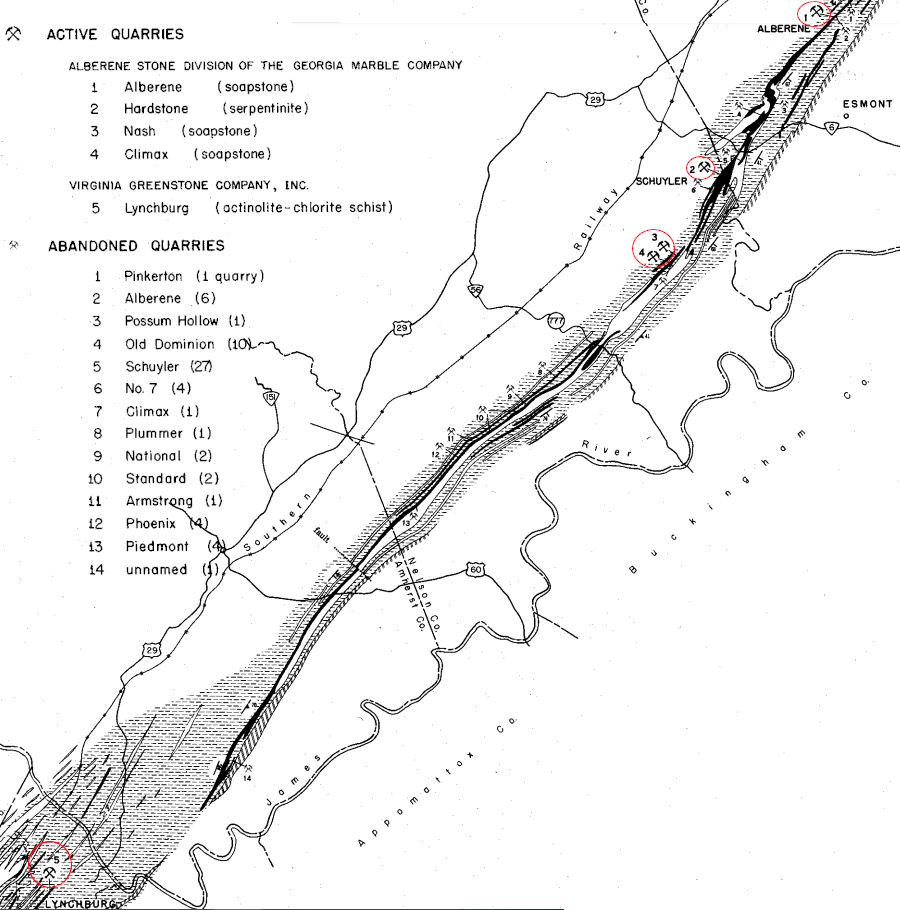

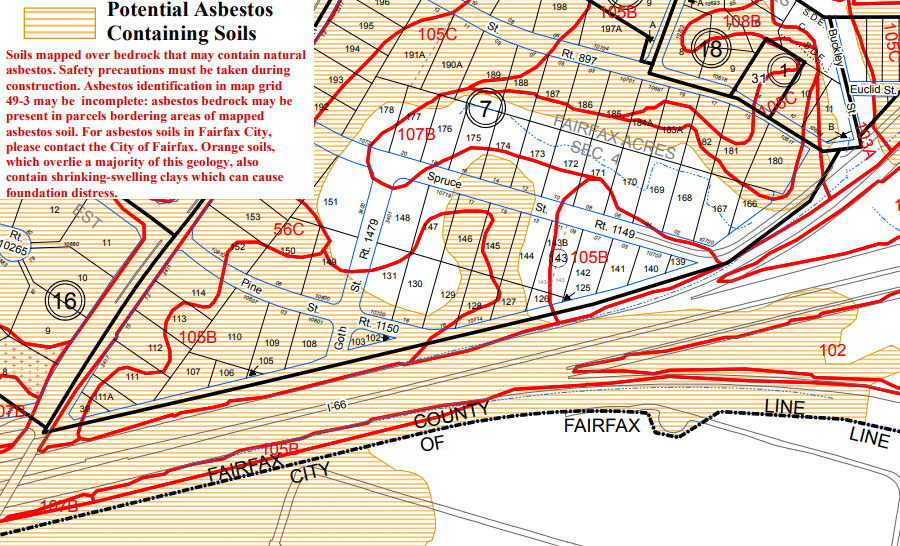

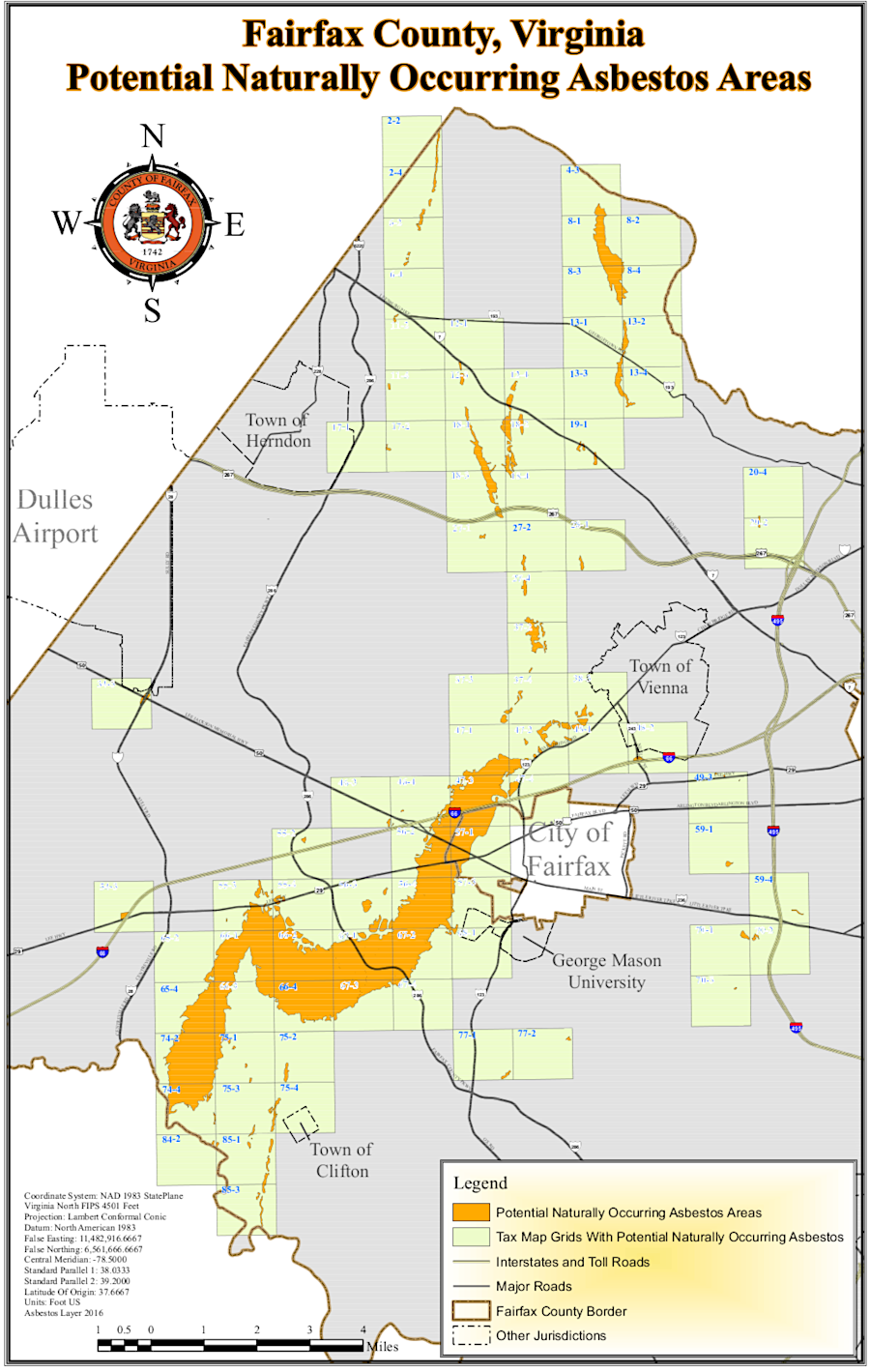

Asbestos fibers may be found in soapstone. Fairfax County has identified 11 square miles where naturally occurring tremolite asbestos, one of the six forms of the mineral, may be disrupted and potentially inhaled during construction projects. In much of the area, bedrock is only two-three feet below the surface:4

counties in which asbestos minerals are known to occur

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Known Asbestos Occurrences In Virginia

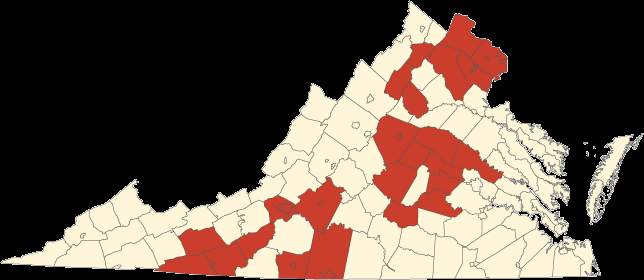

It is possible that exposure to tremolite asbestos is associated with development of a lung cancer, mesothelioma. In 1987, workers building an underground garage at Fair Oaks Commerce Center near I-66 were exposed as small pockets and veins was pulverized. Air drill operators ended up with itching and skin irritation, and construction companies now must provide appropriate personal protective equipment in the areas where asbestos may be mobilized.

Today the bedrock is covered with grass. Whatever asbestos fibers may exist are embedded, and the risk of exposure has been eliminated. The building's owner advertises proudly:5

construction of the underground garage at Fairfax Commerce Center revealed the presence of asbestos in Fairfax County bedrock

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

naturally occurring asbestos has been mapped where I-66 cuts through Fairfax County and the City of Fairfax

Source: Fairfax County Digital Map Viewer, Soils Map, Tile 47-3

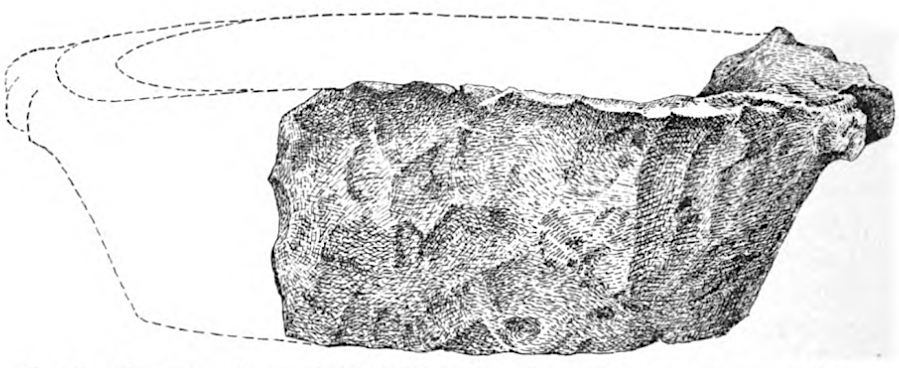

Native Americans recognized that soapstone was soft enough to be carved into bowls, using harder rocks such as quartz. Soapstone has a high heat storage capacity, so once a pot was heated over the coals of a fire it kept stews and soups warm. Soapstone bowls were too heavy to carry on long hunting/gathering migrations, but about 5,000 years ago during the Archaic Period the domestication of native plants made it more suitable to settle for much of the year in one place. Soapstone was used at least 4,500 years ago as a sedentary lifestyle emerged.

The very first geologists in Virginia opened quarries in what are now Fairfax, Orange, Madison, Albemarle, Nelson, Amelia, and Brunswick counties. In Nelson and Albemarle counties, an archeologist identified 20 ancient quarries in 192. They were typically 20-30' wide and 2-3' deep; extracting soapstone did not involve digging a mine.

remnants of soapstone bowl found near Damon (Albemarle County)

Source: David I. Bushnell, Jr., Alberene Soapstone - Slab Selection

Making stone containers for food storage and cooking declined after the introduction of pottery to Virginia about 3,000 years ago. Pots were easier to manufacture, and the raw material (clay) was available in far more places than soapstone. Production of soapstone items lasted longer in the areas where that material was readily available.

soapstone was quarried and worked to make bowls during the Archaic Period

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, A Steatite (Soapstone) Bowl

In some areas the early pottery-makers mixed a little crushed soapstone into the clay as a "temper," to reduce cracking when the pots were fired. Pottery-makers who created at least two distinct styles of Virginia pottery, Smyth Ware from Smyth and Washington counties along the Holston River and Marcey Creek Ware from the Coastal Plain, used soapstone as an ingredient. However, within 500 years of its introduction, clay pottery had replaced soapstone everywhere in Virginia.

Smyth Ware, a type of clay pottery produced along the Holston River, used crushed soapstone as a temper

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Smythe Ware

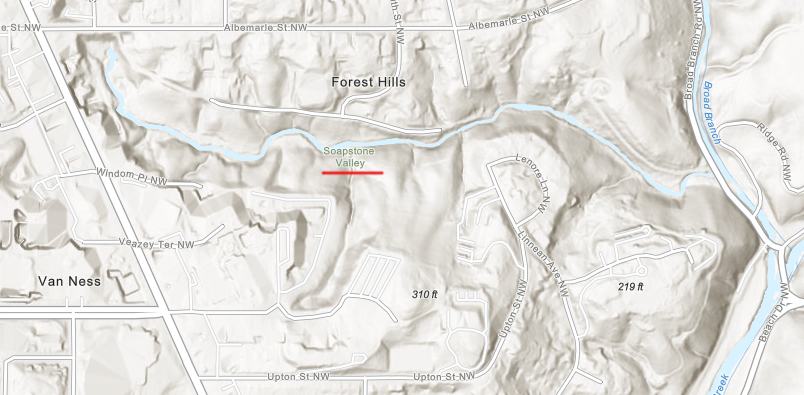

Native American quarries where soapstone was carved are still visible in Fairfax County, including sites at Fairfax Villa Park and near Clifton. At what is now Soapstone Valley Park in Washington, DC, the prehistoric Rose Hill Soapstone Quarry site survived until Connecticut Avenue was constructed in 1897.6

Native Americans quarried soapstone along tributaries to what is now called Rock Creek in Washington, DC

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

visitors to Fairfax Villa Park in Fairfax County can see evidence of soapstone mining by Native Americans about 3,500 years ago

Source: GoogleMaps

Moden soapstone quarries were developed in Albemarle and Nelson counties after the Civil War. The Albemarle Soapstone Company organized in 1883 to mine the soapstone deposit at Johnson's Mill Gap, soon renamed Alberene. "Alberene" was coined from a combination of the name of Albemarle County plus the name of one of the company owners, James Serene. He had been running a soapstone business in New York, and came to Albemarle because the sources there were being exhausted and he needed to find a new supply of soapstone. He ended up mining the largest deposit of soapstone in the world.

Alberene developed as a company town, dependent upon quarrying and processing soapstone. Chimneys, foundations, and other components of the company-built houses were made from scrap soapstone.

Products, including material for laundry sinks, were hauled by horses and mules north across Fan Mountain to the North Garden depot of the Virginia Midland Railroad. In 1895, the General Assembly chartered the Alberene Railroad. It had the choice of building north to what had become the Southern Railway, or south to the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railway running along the James River. In 1888, 11 miles of track were built going south past Esmont to the James River; that made it possible for loaded trains to go downhill.

The Virginia Soapstone Company, founded in 1893, opened a quarry in Nelson County to extract soapstone from a vein that was two thousand feet in length and three hundred feet in width. One of the two primary investors was Dr. Carl "Max" Wiehle, who had previously invested with his other partner in the Virginia Serpentine and Talc Company in Fairfax County. Dr. Wiehle planned to develop a model community around his talc mill, but that did not happen until the 1960's when Robert E. Simon developed Reston.

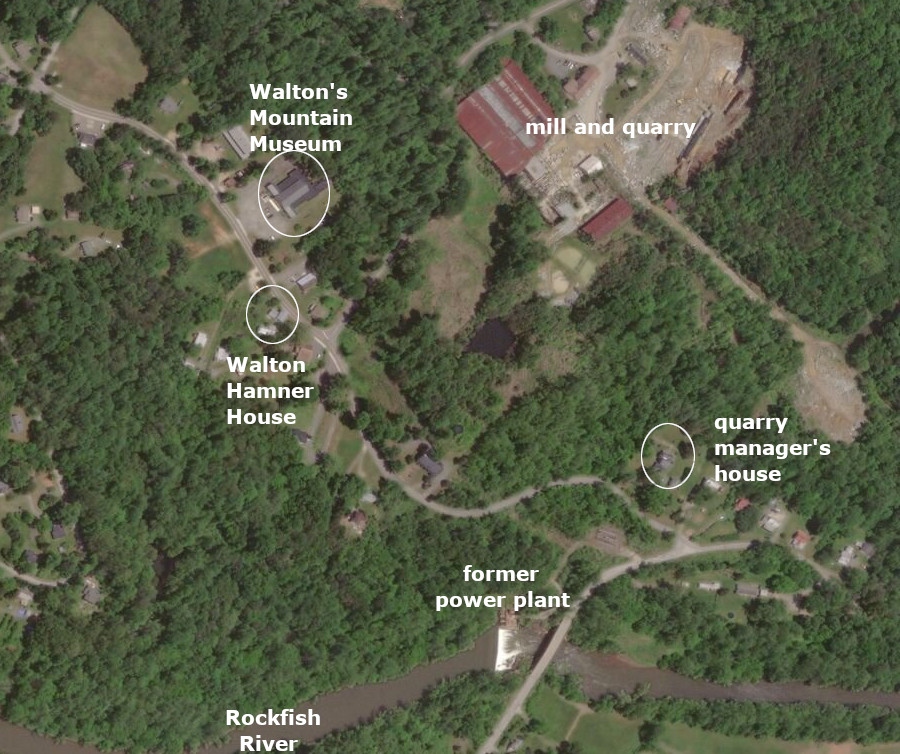

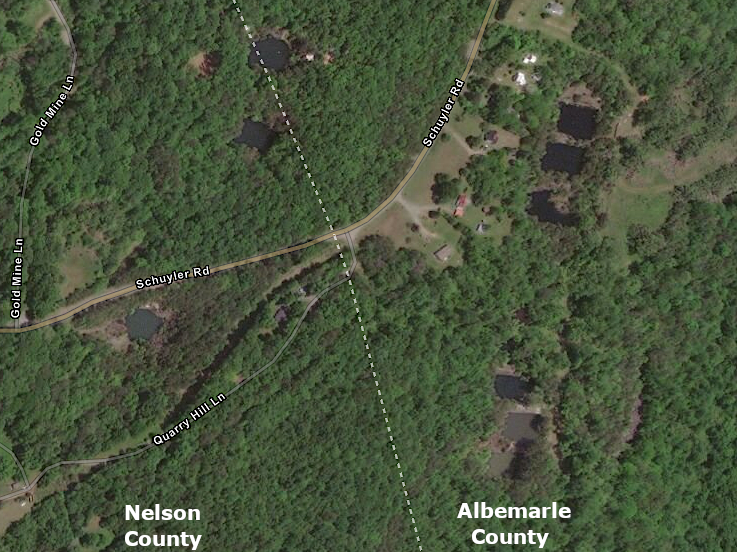

The Virginia Soapstone Company built a separate railroad from its quarry in Schuyler to the Virginia Midland Railroad depot at Rockfish in 1901. Schuyler had developed in the 1840's, after William Walker established a sawmill that took advantage of the waterpower provided by the Rockfish River. The community around Walker's mill was known as Tan Top and Aurora. When his son proposed a post office in 1886, there was already a post office elsewhere in the state named "Tan Top." Schuyler Walker then used his name for the post office, and was appointed as the first postmaster there.

It became an industrial village housing workers who quarried and processed soapstone. There were eight quarries in Nelson County at Schuyler, with another eight quarries were just across the boundary in Albemarle County. Most houses were built far enough away from the quarries to avoid noise and dust, but some were built close enough that workers could walk out of their back door to get to their job site. Houses were basic, many with two rooms downstairs and one upstairs while others had five rooms.

Some African-Americans found jobs at the quarry, but lived in a separate community in Albemarle County east of Schuyler. That area also had company-owned dwellings and a school. At Schuyler, the company store sold everything from "coffins to coal." At one point, over 2,000 people were working in the soapstone quarries and mills. In 1919, the largest soapstone manufacturing plant in the world was the mill at Schuyler.

modern-day Schuyler in Nelson County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

there were eight quarries in Nelson County near Schuyler, and eight in Albemarle County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

It built two story, wood-frame houses for the workers in Schuyler. The Virginia Soapstone Company also built two dams with hydropower stations on the Rockfish River, one at Walker's Mill in 1899 and another at Harris Bridge closer to the mill in 1904. The company supplied electricity and water to the workers' houses as well as to the mill. In 1921, a third power station was completed downstream from the Harris Bridge dam.

there were three power plants built for Schuyler's soapstone operations (the 1899 dam was at Walker's Mill)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Schuyler Railroad was built in 1901 as an electrified trolley. It was reorganized as the Nelson & Albemarle Railway and converted to use steam-powered locomotives. The Nelson & Albemarle Railway ultimately acquired what had started as the Alberene Railroad, which had been folded into the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railway in 1900. Through the Nelson & Albemarle Railway, the quarry operators had rights to transport stone to the Southern Railway at Rockfish and the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway at Warren. The Southern shipped to customers north and south of Schuyler; the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway shipped to customers to the east and west.

the soapstone quarry at Alberene initially hauled products by wagon to the North Garden railroad depot, before building the Alberene Railroad south to Warren

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Buckingham, VA 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1892)

In 1904 the Albemarle Soapstone Company merged into the Virginia Soapstone Company, which had been mining at Schuyler (in Nelson County) since 1893. The soapstone deposit was mined out at Alberene in 1908, but the mill was still fully operational. Extending the Nelson & Albemarle Railway to Alberene allowed the company to continue to use the equipment for processing blocks of stone, until operations ceased at Alberene in 1916. After 1916, the company name was changed to the Virginia Alberene Corporation.

The company stopped operations briefly in 1934, and the railroad track from Esmont to Alberene was abandoned during the Great Depression. The company was reorganized and renamed the Alberene Stone Corporation, and restarted business. At one point, the company purchased a marble quarry near Knoxville, Tennessee and shipped it to Schuyler for processing.

A 1944 flood destroyed the railroad connection to the Southern Railway at Rockfish. After that, all shipments sent east through Warren to the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad. Passenger operations had been maintained on the line to Rockfish to enable workers to commute to the mill. All passenger service on the remaining Nelson & Albemarle Railway track ended in 1950, and freight service ended in 1963.7

soapstone quarries at Alberene are now water-filled ponds, separated by the "bridge walls" that were left as supports when rock was excavated

Source: Google Maps

the bridge and hydroelectric dam on the Rockfish River at Schuyler were washed out by Hurricane Camille in 1969

Source: Library of Virginia, Aerial View of Schuyler Dam

damage to the hydroelectric dam on the Rockfish River at Schuyler by Hurricane Camille in 1969

Source: Library of Virginia, Schuyler Dam and Bridge

the power plant at Schuyler was washed away by Hurricane Camille in 1969

Source: Library of Virginia, Smokestack at Schuyler Dam

remains of the power plant at Schuyler in 2014

Source: Kipp Teague, old hydro-electric plant at Schuyler, Virginia

Sales were high during the post-World War II baby boom and associated housing boom, and Georgia Marble purchased the Alberene Stone Company in 1956. It reopened the Alberene quarries to obtain more material.

The Jim Walter Corporation, a conglomerate that included a unit which built houses, purchased Alberene Stone in 1966. It operated the quarries and mill at a lower intensity for several more years.

In 1969 Hurricane Camille flooded the quarry, washed away the power plant on the Rockfish River, and damaged the mill at Schuyler. Other companies later restarted hydropower operations at the dam, independent of the soapstone business.

Before Hurricane Camille in 1969, there had been 600 employees. After the flood, Jim Walter Corporation did not reinvest the insurance payment back into the plant. About 200 employees were kept working until the operation closed in 1973.

An investor in mineral properties, Vance Wilkins, purchased the 9,000 acres, facilities, and equipment and reopened in 1976. In 1973, he had also purchased the American Cyanamid Company titanium mine on Piney River nearby. He sold that business in 1976, and in 1977 was elected to the Virginia General Assembly. He sold the Alberene Stone Company (but retained most land rights) to a local investor in 1983. That investor sold it to a Finnish company in 1986, Tulikivi.

It invested $6-12 million to modernize the mill and restarted operations again in 1987. Tulikivi manufactured heaters for the high-end market ("Tulikivi" is Swedish for "fire stone"). The stone stoves, once heated, warmed a room for 48 hours. However, there were too few buyers of $7,000 heating stoves in North America.

Local investors purchased the New Alberene Stone Company in 1998, renaming it the New World Stone Company. It began to process blocks of stone which had been cut from the hillside decades earlier, and developed the site as an artists colony more than an industrial operation.

Virginia Soapstone Ventures, a new set of local investors that included a local veterinarian, took control and focused on refurbishing the mill again. In 2010 the new company hired managers and an experienced quarry operator. The small group of investors lacked adequate funding to start large-scale operations again, and sold the company to Polycor in 2014.

Polycor, which was based in Quebec and also owned Georgia Marble, was looking to expand the types of material it could offer. Its only other option for acquiring slab soapstone was to purchase a quarry in Brazil, and Polycor operated only in the United States and Canada. Polycor acquired the oldest operating quarry (dating back to 1888) and the last producer of architectural-grade, heat and acid resistant soapstone in the United States.8

the Schuyler quarry cut sideways into the hill to access soapstone veins

Source: GoogleEarth

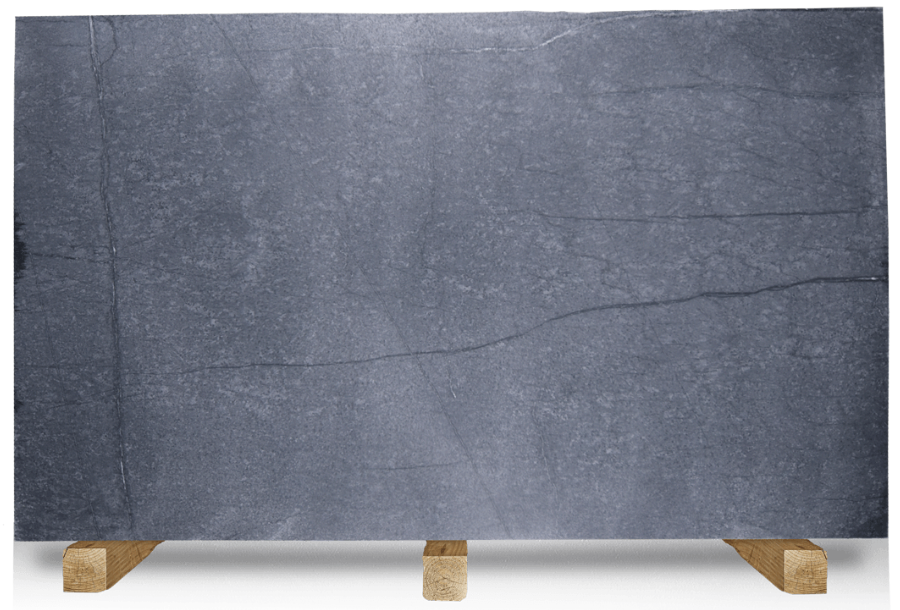

the Old Dominion quarry is now the source for most soapstone slabs

Source: GoogleEarth

from a Schuyler quarry, Polycor still manufactures slabs of soapstone for heated flooring and other uses

Source: Polycor, Alberene Soapstone

Virginia producers of soapstone in the Blue Ridge sawed it into dimension stone, or slabs. They were then cut to specific dimensions to make stoves, fireplaces, furnace and chimney linings, insulators for electrical appliances, laundry tubs and sinks, floor tiles, and various architectural decorations. The stone's resistance to chemicals made is particularly suitable for tables and other surfaces used in laboratories. Material from a quarry in Fluvanna County was used for crayons.

The Lynchburg Marble and Granite Works (acquired in 1929 by the Virginia Greenstone Company) opened a quarry within Lynchburg at what today is the intersection of Daniel Avenue and Harper Street. First step to open a quarry was removing the overburden of soil to expose a face of rock. That was followed by cutting channels into the soapstone perpendicular to the natural foliation of the rock layers.

The Alberene Stone Company chose to drill holes and then connect them. Its quarries were as much as 275 feet deep, with excavations cut in 100- to 150-foot square sections. A 25- to 40-foot wide bridge wall was left between quarries to support cranes and other excavation equipment.

Both companies then cut into the bedrock at the bottom between channels. Individual blocks of stone roughly three feet wide, four feet deep, and seven feet high were separated from each other by drilling more holes and using wedges to pry them apart. Cranes then lifted each block, some weighing as much as 10 tons, to the surface and placed them onto a truck or railroad car for transportation to the mill.

the Virginia Greenstone Company in Lynchburg was at the corner of Daniel Avenue and Harper Street

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Much of the stone ended up as waste material, not worth moving from the quarry. Natural zones of weakness caused the rock to break into small, irregular pieces. Where seams had allowed groundwater to penetrate, rock would have unacceptable mineral staining from iron oxides.

Blocks which reached the mill were sawn into slabs. Large gang saws slowly moved through a block, cutting slices roughly 1" thick. Sand, lubricated with water, was used rather than a sharp blade to cut through the stone. Cracks in each slice were identified by spraying with water, then blowing compressed air on the slice. Places where water remained were marked for later disposal, and the rest of the slice was carved into the shapes needed for particular products. The last cuts to specified dimensions were done with circular saws, using diamond-tipped blades. The last step was to grind and buff the surfaces to obtain the desired polish.9

Polycor re-opened the Old Dominion quarry two miles from the mill and cut new blocks using specialized chain saws 20' long, diamond wire, and water. The first blocks carved from the ground are 30' x 30' x 5' in size. They are then reduced to roughly 5.5' x 9' x 3' to eliminate the stone with unacceptable seams, cracks, and stains. Final blocks weighing up to 24 tons, with a resin coat to reinforce the integrity of the blocks, are shipped to one of Polycor's mills for fabrication.

After blocks are sliced, slabs are heated to 100°F in the mill, then reinforced with resin and backing to reduce breakage and increase commercial yield. Each slab has a different pattern, so the Alberene Soapstone Company posts photos online. Customers then choose the specific slab they want, after assessing its clarity, size, color and veining. Using soapstone for countertops has been popularized by Martha Stewart and the "This Old House" television program. The window sills of Rockefeller Center in New York City and Martha Stewart's kitchen counter are both made of soapstone.

The company president noted in 2013: that old quarries could be re-opened to provide stone of different character:10

In the past, some soapstone companies ground their soapstone into powder. At the time, the risks associated with asbestos fibers mixed in with talc were not recognized. In 1908, New York produced most of the ground soapstone in the United States; only 10% of Virginia's production was powdered::11

The ground soapstone was used in "foundry facings," the coating on sand molds that kept the final product from sticking to the mold. Powdered soapstone was also an ingredient added to paint:12

The Blue Ridge Talc and Soapstone Company in Fairfax County, and the Blue Ridge Talc Company with its King-Ramsey Quarry in Henry County, were two remaining producers of ground talc in Virginia at the start of the Great Depression. Quarries that focused on producing dimension stone also created powder from rock scraps as a side product. Alberene Stone purchased a competitor, the Alberoyd Company, which ground up scrap soapstone for use in asphalt roll roofing, as a fire retardant in mines, and for facing molds. A "dust plant" was constructed near Damon to expand on the production of powder as a by-product, and a replacement dust plant constructed in Schuyler in 1947.

The Fairfax County quarry near Clifton closed in 1942. The Blue Ridge Talc Company was the last powder-producing operation to close. It was owned and operated by members of the Kitson family from the 1880's until the facility shut down in 2002. The operation was described in 1961:13

in 1931, the Blue Ridge Talc Company still was quarrying soapstone on the border of Henry and Franklin counties

Source: Virginia Minerals, Talc, Soapstone, and Related Stone Deposits of Virginia (Figure 1)

Many of the small quarry sites in Nelson and Albemarle counties were abandoned as suitable rock near the surface was exhausted. Today, the area is pockmarked with square ponds that reveal the sites of old operations, with the tops of the bridge walls separating the ponds.

Earl Hamner, Jr. made the area famous through his creation of "The Walton's" television show. It emphasized the wholesome family life of a fictional Blue Ridge family, but was based on his childhood growing up in Schuyler. His father had worked for the Alberene Stone Company. Taking advantage of the tourism generated by the show, the former Schuyler Elementary School was converted into the Walton's Mountain Museum.14

Tourists are also welcomed at the Quarry Gardens at Schuyler, on 600 acres that a New Jersey couple purchased in 1991. Two quarries which had operated between the 1950's-1973 were converted into a not-for-profit public garden with 30 galleries of native plant communities and two miles of trails, as well as exhibits on soapstone mining history. Five of the pits on that quarry have 45' high vertical walls above the water level, and another 45' of wall extending to the bottom of the pits. A sixth pit was filled with overburden and chunks of soapstone not suitable for processing and sale.

In 2015, 400 acres were placed in a conservation easement. In 2020, The gardens were designated as a Virginia Native Plant Society Registry Site in 2020, and a prescribed fire that year helped to control invasive species and maintain natural regeneration.15

the Quarry Gardens at Schuyler have repurposed two old quarries as backdrops for native plant gardens

Source: Quarry Gardens at Schuyler

in Fairfax County, construction projects in selected areas could release airborn asbestos fibers that threaten worker health and create public relations challenges

Source: Fairfax County, Construction Safety in Areas of Naturally Occurring Asbestos

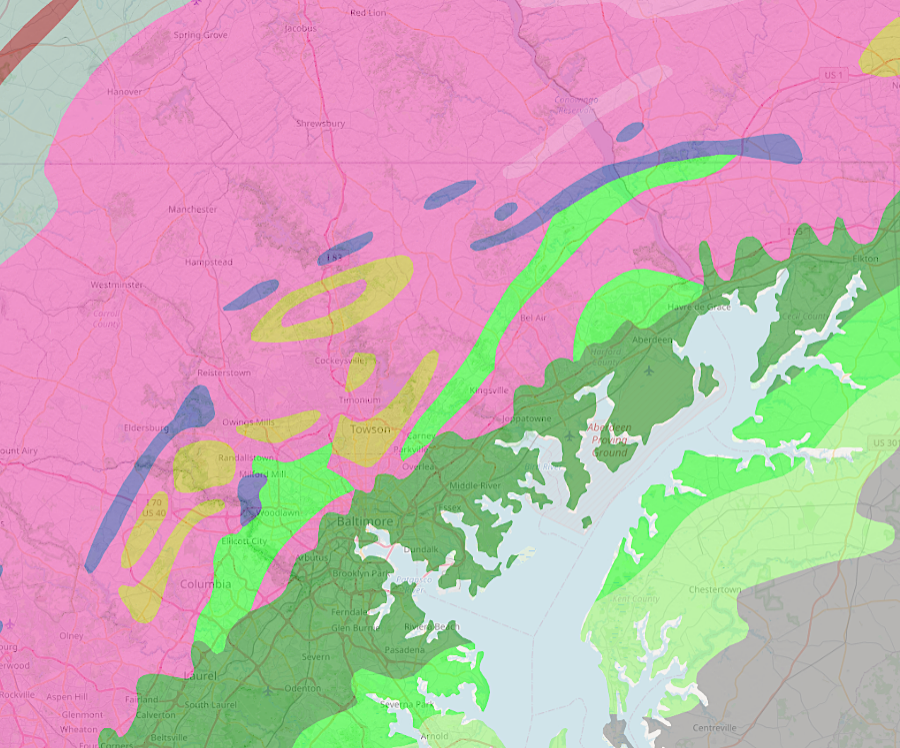

ultramafic rocks (dark blue) with soapstone are exposed from Virginia to Pennsylvania

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Geology of the conterminous United States