Glen Lyn (Giles County) was too old to justify upgrading further to meet Clean Air Act standards

Glen Lyn (Giles County) was too old to justify upgrading further to meet Clean Air Act standards

After World War II, Virginia's utility companies met the increased demand for electricity by constructing power plants fueled primarily by coal. That energy source was cheap and readily available. Coal-fired power plants could be constructed anywhere near a railroad, so long as there was an adequate supply of fresh water to cool the steam used to spin turbines.

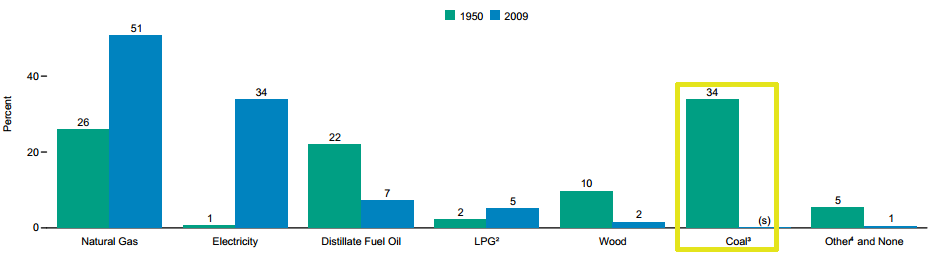

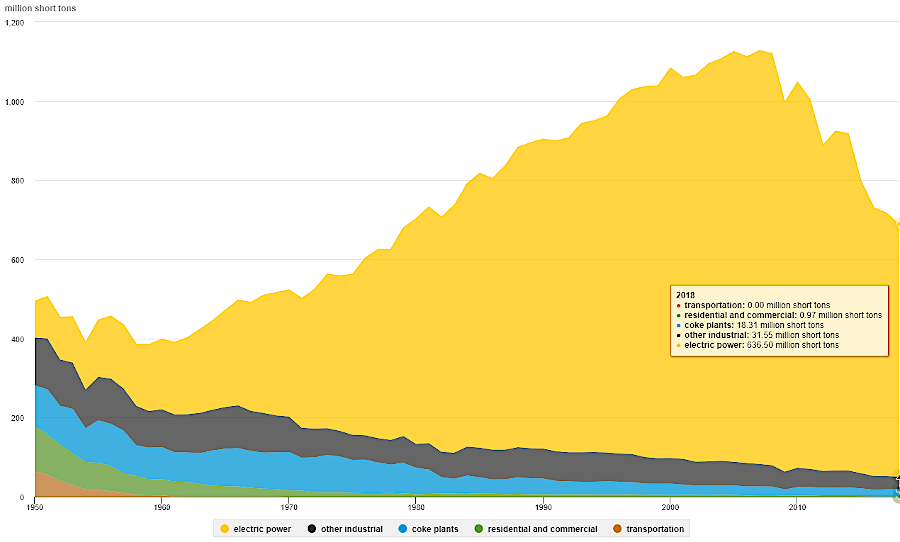

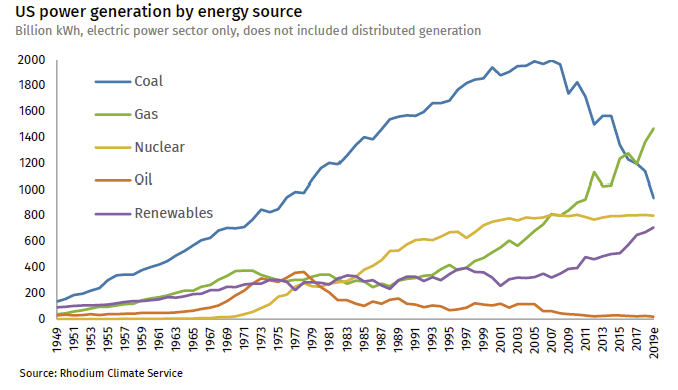

since 1950, use of coal for directly heating houses has virtually disappeared in the United States - but use of electricity generated by coal increased

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Review 2011, Type of Heating in Occupied Housing Units, 1950 and 2009 (Figure 2.7)

50 years later, that pattern changed due to both pollution control measures and economics. Utilities have closed old coal-fired power plants that were at the end of their useful life, or altered them to use other fuel sources, rather than upgraded coal-fired power plants to burn coal for another 50 years. A Washington Post article in 2014 described the old power plants as an "aging fleet of clunkers," and noted that the facility at Glyn Lyn in Giles County was the second-oldest coal-fired plant still operating - old enough to be collecting Social Security.1

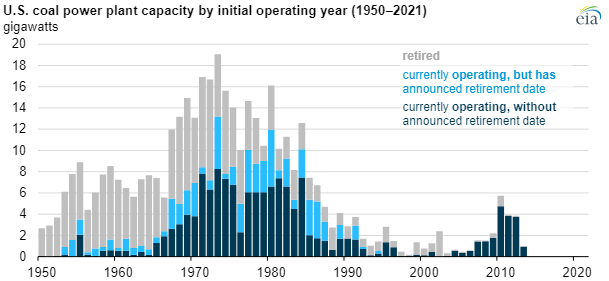

the surge in constructing coal-fired power plants was matched by a surge in retiring those facilities about 50 years later

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Of the operating U.S. coal-fired power plants, 28% plan to retire by 2035 (December 15, 2021)

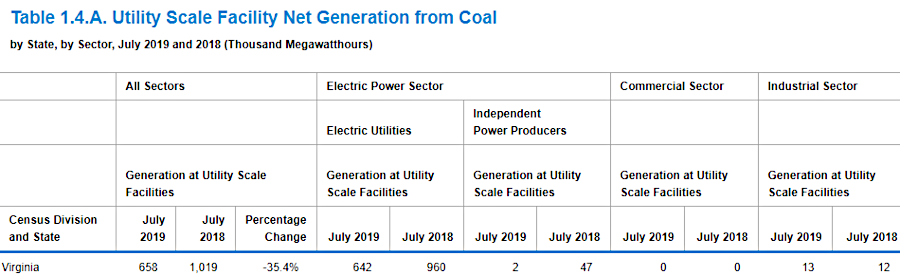

in just one year, electricity generation from coal-fired power plants dropped by over one-third in Virginia

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Electric Power Monthly (Data for July 2019)

Dominion Power has closed down old coal-fired power plants built just after World War II, such as the facility at Glyn Lyn. The utility chose to built new plants to generate electricity that were fueled by natural-gas. Three small coal-fired facilities at Altavista, Hopewell and Southampton were converted to burn wood waste from forestry operations, allowing Dominion to retain jobs in those communities and meet a small portion of its voluntary goal to generate 15% of electricity (excluding nuclear) from renewable resources.

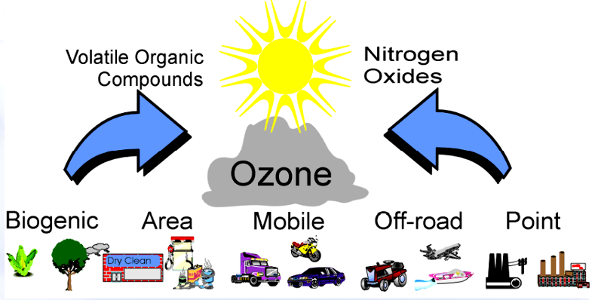

In 2003, Dominion converted the two last coal-fired boilers at the Possum Point plant in Prince William County (units #3 and #4) to natural gas in order to meet air quality mandates. The metropolitan Washington DC area was in Clean Air Act "nonattainment" status for ozone as well as fine particles smaller than 2.5 microns. Emissions from burning natural gas at Possum Point reduced nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur oxides (SOx), and particulate matter (PM2.5) from that point source. Eliminating the use of coal smoothed the approval by Virginia Department of Environmental Quality of a new Unit #6 at Possum Point, producing 559MW from natural gas.2

regulation to reduce air pollution required point sources such as power plants to cut emissions of criteria pollutants, especially gases that sunlight converted into ground-level ozone

Source: Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, Metropolitan Washington, DC-MD-VA Air Quality Status 2012

Five generators at the Potomac River Generating Station were built between 1949-57 on the Potomac River, on the upstream edge of Alexandria, to supply 482MW of electricity to fast-growing Washington, DC. The five stacks of the power plant were built unusually low. Taller stacks would have dispersed pollution across a wider area, following the traditional approach where "dilution is the solution to pollution," but airplanes flying into National Airport would have been affected.3

low stacks at power plant in Alexandria, before closure in 2012 and removal of coal pile

The Alexandria plant was owned by the Maryland utility PEPCO until deregulation. In 2000, PEPCO sold the plant to Mirant, a private "merchant" firm that had no retail customers. Mirant bet that it could profit by generating and selling electricity at wholesale rates to utilities that would distribute it to customers. PEPCO was required by Maryland's 1999 Electric Utility Industry Restructuring Act to break up its vertically-integrated business and separate its generating and distribution capabilities.4

Residents complained about coal dust coating cars/window sills, even staining laundry. A 2003 meteorological study funded by two local citizens showed that soot deposition was concentrated in the local neighborhood of Alexandria.

Fifty years after the plant was built, the focus was on health effects of fine particles and mercury creating a local health hazard. Mercury, a minor component in the coal, is vaporized in the burning process. As hot exhaust cools in the air after leaving the power plant stacks, the plume of gas moved over Alexandria and then to the northeast (typically). Mercury cooling from the exhaust gas and soot particles may be deposited near the plant - with "downwash" creating a "hot spot" of lung damage and potentially-toxic soil in the local area.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) issued an air quality permit for nitrogen oxide emissions from the Potomac River Generating Station in 2000, which Mirant violated in 2003. DEQ and then the Federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) settled with Mirant in 2004, but the City of Alexandria took another approach that year.5

the coal-fired power plant at Alexandria polluted the local neighborhoods - but all the electricity went to Washington, DC

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Alexandria 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (Revision 1, 2013)

The city tried to use its zoning power to force the plant to close. The plant was constructed before the city created its first zoning ordinance, so use of the site for a power plant was vested (grandfathered) when the zoning ordinance was passed. A retroactive application of zoning that would have forced the plant to close would be a "taking," under the Fifth Amendment. The city tried a creative approach, claiming violation of a 1989 Special Use Permit (SUP) granted by the city entitled Alexandria to revoke all permissions for operating the entire plant.6

The State Supreme Court rejected this effort, while providing some perspective on why an industrial use that was acceptable 50 years ago and had been authorized under Special Use Permits (SUP's) had become a problem for the city. Bottom Line: new residential development, followed by citizen activism, had made the industrial designation inappropriate: (Note: emphasis added):7

In 2012, GenOn Energy, the utility that owned the facility, closed it permanently. The old facility was relatively inefficient, the cost of coal was high compared to natural gas, and local opposition eliminated any opportunity for tax subsidies or economic incentives to maintain operations.

The last coal-fired power plant constructed in Virginia was the 585MW Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center in 2012. The last coal-fired power plant constructed in the United States was the Sandy Creek Energy Station in 2013, in Texas.

The Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center was built on a former coal mine near St. Paul in Wise County. The construction of that power plant was an economic stimulus project spurred by the state, as well as a response by Dominion Power to the need for increased generation capacity.

Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center (Wise County)

Source: Dominion Resources

In 2004, the General Assembly passed SB651, which directed construction of a power plant to burn coal in southwestern Virginia. The law had multiple goals, but primarily it was designed to increase economic development, spur jobs in that area, and increase property taxes paid by commercial development to a local jurisdiction in the area.

The plant burns "gob" coal, helping to remove the piles of coal waste that accumulated at mines and processing plants. That coal was judged at the time to be of so little value that it was not worth shipping to customers. Today the energy value in the waste is sufficient to justify trucking it up to 45 miles to the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center. Over time, 186 of the 245 identified coal waste sites in Southwest Virginia could be eliminated by burning the material at the power plant.

When the specific site was chosen in 2006, Dominion Resources announced that it expected the plant to provide 75 jobs when operating, and to support 250 coal mining jobs. A later Fact Sheet claimed, beyond the short-term benefits in the construction phase:8

Much of the opposition to construction of the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center centered on state approval of the air quality permit. The utility company, Dominion, "sweetened" the deal by committing to convert the Bremo Bluff power plant from coal to natural gas, reducing ozone that might affect Northern Virginia. The "Hybrid" part of the project referred to its ability to create 20% of the electricity from biomass by burning wood waste.

Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center complex near St. Paul

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Saint Paul 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (Revision 1, 2013)

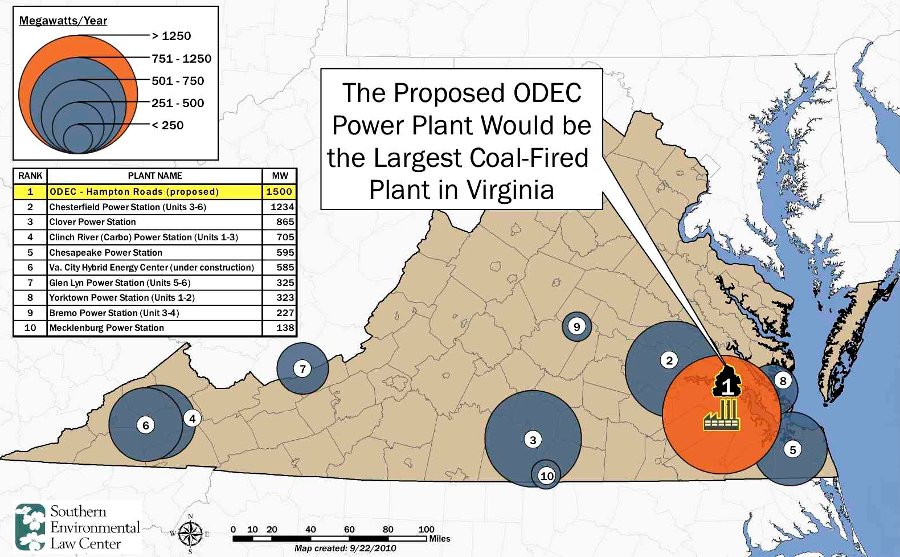

The Old Dominion Electric Cooperative (ODEC) proposed to build a new coal-fired power plant in Surry County. There was both support and opposition in the local area to the proposed Cypress Creek Power Station. There were only 272 residents of Dendron in 2010, so local opponents had limited resources to participate in the legal and bureaucratic decision process, but non-local environmental groups such as the Sierra Club joined the fight.9

ODEC also considered a site in Surry County, keeping open its political options. The Town of Dendron ultimately approved the project, anticipating an economic stimulus from the $5 billion project. However, the benefits of natural gas as a fuel - rather than local opposition or support - is what altered the utility's plans. In April 2013, the cooperative announced that it would build a new power plant fueled by natural gas in Maryland.10

in 2013 ODEC cancelled the proposed Cypress Creek Power Station, which would have been the largest coal-fired generating plant in Virginia

Source: Wise Energy for Virginia, Virginia'??s Largest Coal Plant Proposed for Hampton Roads

Compared to natural gas, coal became an expensive fuel at the start of the 21st Century. American Electric Power (through its subsidiary, Appalachian Power) decided to close or convert all of its coal-burning power plants in Virginia by 2016. After 50 years of service, the facilities built after World War II had reached the end of their useful life.

Rather than upgrade the plants to increase efficiency and also to meet Clean Air Act mandates, the utility chose to close its 335MW plant at Glen Lyn (Giles County), close one of the three units at the Clinch River Power Plant, and convert the other two units at Clinch River to burn natural gas instead of coal.

The Glen Lyn plant had opened in 1919 with the capacity to generate 15MW. That was expanded in 1944 to add a 95MW Unit 5, which at the time was the largest coal-fired generator in the southeastern states. Appalachian Power started up Unit 6, generating 240MW, in 1957. All generators depended upon coal for fuel.

The 13 original boilers and four turbines were taken offline in 1971. Units 5 and 6 were shut down in 2015. When the plant stopped operating, Giles County and the Town of Glen Lyn lost jobs and $630,000 in annual property taxes.

Efforts were still underway in 2024 to find some industrial use for the 45,000 square foot building, with 60' high ceilings and overhead cranes that could lift up to 100 tons. If not repurposed, Appalachian Power was expected to tear it down. After removal of the coal ash to a lined landfill, the Giles County Administrator said:11

baghouse at Glen Lyn coal-fired power plant, trapping particulates in order to meet Clean Air Act standards=

The State Corporation Commission (SCC) also blocked plans by American Electric Power to purchase half of a coal-fired power plant in West Virginia in order to replace the generating capacity the company was closing. The SCC objections noted that the purchase would make American Electric Power dependent upon coal for 87% of its generating capability.12

The Virginia regulatory agency based its decision on the need for greater diversity of energy sources. However, the SCC's action incentivized a separate company, Competitive Power Ventures, to propose building a new 700-megawatt power plant in Virginia.

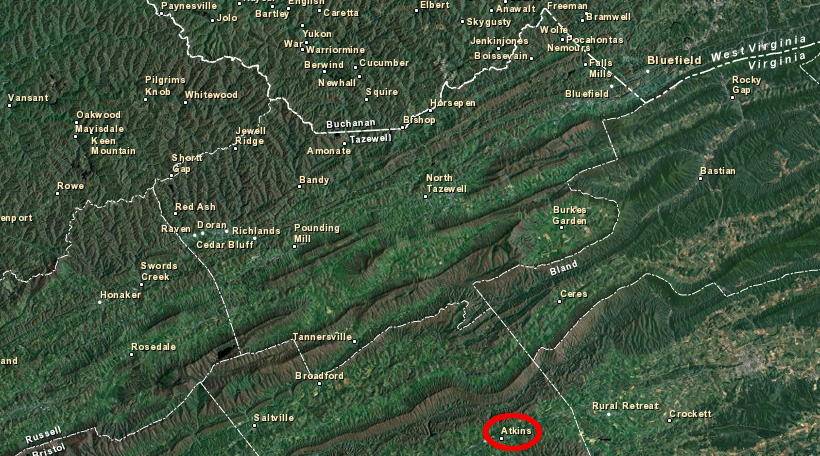

Competitive Power Ventures planned to build the CPV Smyth Generation Project at Atkins in Smyth County because of easy access to natural gas via the East Tennessee Pipeline, the ability to distribute power via the 765-kilovolt Broadford-Jackson Ferry transmission line already constructed by American Electric Power, and the economic incentives offered by the Smyth County Industrial Development Authority. The power plant at Atkins would have paid $5 million annually in local property taxes, increasing revenue for Smyth County by nearly 25%.

Coal is available nearby with low transportation costs, but power plants are long-term infrastructure investments. Competitive Power Ventures looked at the projected cost of natural gas for the next 20-40 years vs. coal and chose gas over coal.

Competitive Power Ventures was not a part of any utility company, and it proposed a "merchant plant" without a guaranteed customer. The 765-kilovolt Broadford-Jackson Ferry transmission line could carry the electricity to utility customers in North Carolina, Tennessee, or even to supply Dominion Power in Virginia, further reducing demand for electricity generated by coal.

American Electric Power declined to purchase power from the proposed facility, indicating it has an adequate supply of electricity for the next decade. Competitive Power Ventures decided in 2016 not to build the facility and try sell its electricity to other customers in the PJM grid.13

Dominion's Chesapeake Energy Center burned coal brought by rail from Appalachian mines to produce electricity

Source: Google Maps

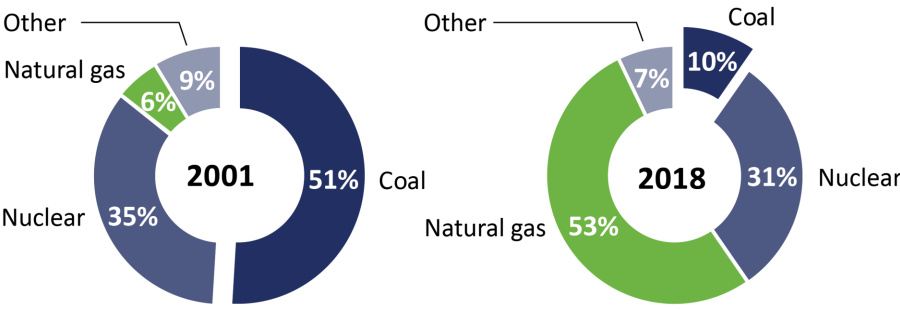

Action by the SCC to encourage electricity generation from renewable resources and natural gas, while discouraging generation from coal, is a clear signal that the state's traditional support for the coal industry has waned. The Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center in Wise County will be the last new power plant fueled by coal that will ever be constructed in Virginia.

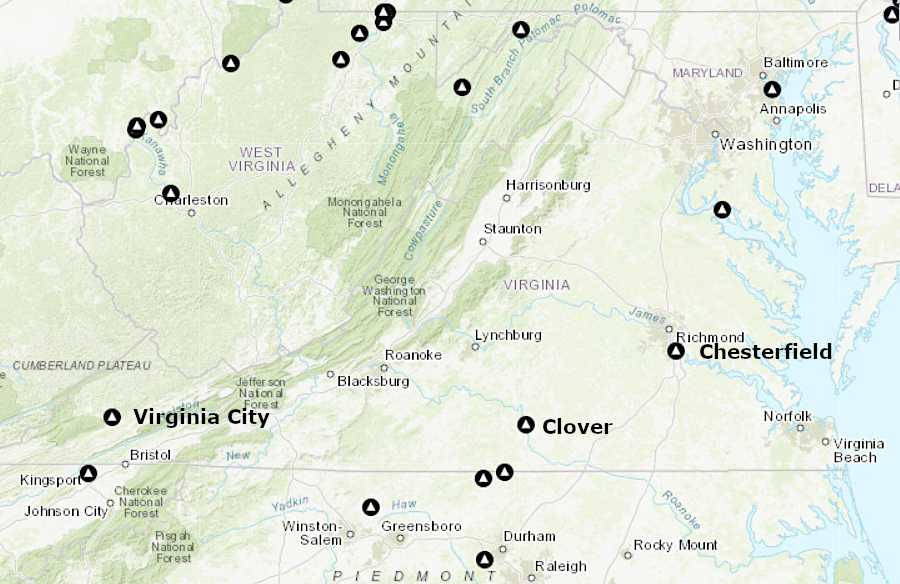

The Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center certainly will be the last operating coal-fired power plant. In 2021, solar facilities generated more electricity (3,365 gigawatt-hours) than coal (3,130 gigawatt-hours)

By 2021, Dominion Power was operating just one other coal-fired power plants in the state, plus Mt. Storm in West Virginia. The Clover Power Plant was scheduled for closure by 2025, in accord with the Virginia Clean Economy Act passed in 2020. The utility company announced its intention to keep using the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center until closing that facility in 2045, because:14

the CPV Smyth Generation Project in Atkins (Smyth County) is near Appalachian Plateau coal mines, but proposed to use natural gas from the East Tennessee Pipeline

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Research into clean coal technology was applied at the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center. It uses fluidized bed technology, allowing the plant to burn low-quality coal that previously had been discarded in "gob piles," plus wood waste.

Coal mining in Southwest Virginia required separating commercially-valuable coal from waste rock; shale and sandstone did not burn. The waste rock was known as "garbage of bituminous" or gob, but also called culm, boney and slate. Waste was simply discarded, creating piles that included low-quality coal that were prone to catch fire. Creation of uncontrolled gob piles ended after passage of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act in 1977. There may be 50-100 million tons in 105 old gob piles scattered across Southwest Virginia, covering more than 421 acres.

Reclaiming old gob piles is an environmental challenge. If left exposed, piles generate acid drainage and release fine coal particles that pollute local streams. If buried, spontaneous combustion can trigger underground fires with sulfurous smoke.

Despite the environmental hazards, there are other abandoned coal mines that are even greater risks, so gob piles rarely qualify for funding from the Abandoned Mine Lands program. Burning the low-quality coal in the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center reduces the cost of the cleanup. The coal-fired power plant mixes the gob with regular coal and occcasionally other fuels because using more than 25-30% gob clogs up the materials handling equipment.

The largest gob pile is at Clinchco, making it the most economical to mine for the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center. By one estimate, it is:15

Source: Explainer: The Environmental & Economic Benefits of GOB Removal to Southwest Virginia

The plant also has the potential to capture carbon dioxide (CO2), a pollutant that contributes to climate change. However, no funding has been identified to implement capture and sequestration of carbon dioxide in underground geologic formations in Virginia.

The US Department of Energy invested in a different coal-fired power plant in Kemper County, Mississippi, to demonstrate how CO2 could be controlled, in anticipation that the Environmental Protection Agency would succeed in issuing regulations that require new coal-fired power plants to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 20-40%.

The economics of carbon capture and sequestration at the Mississippi plant were improved because the CO2 could be piped to an old oil field and used to enhance recovery of remaining droplets of oil underground. Similar oil fields are not available in Virginia, so some other technique will be required if coal-fired power plants in Virginia are to find a way to use waste CO2.16

between 1950-2018, use of coal to generate electricity peaked

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Coal explained

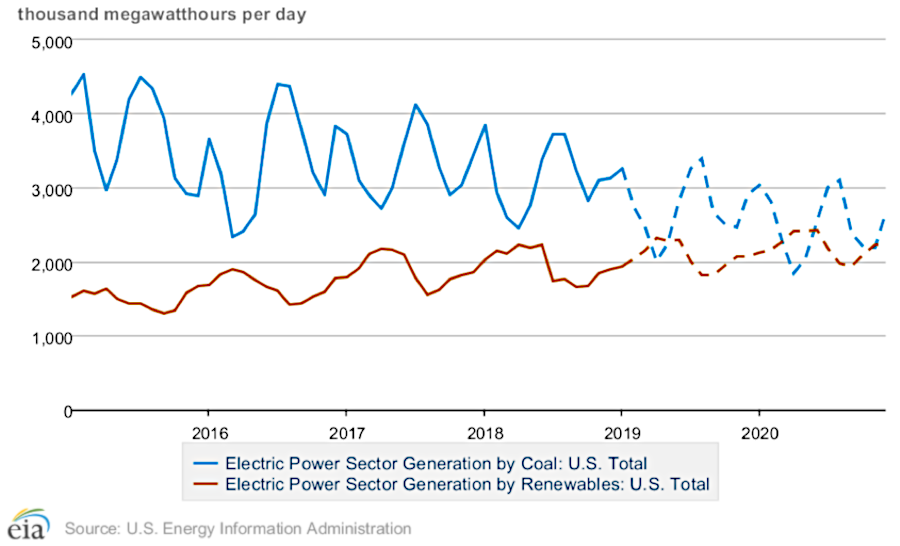

In April, 2019, electricity generated by hydro, biomass, wind, solar and geothermal plants exceeded electricity generated by coal-fired power plants in the United States. In 2019, coal-fired power generation dropped by 18%, dipping to the level of generation in 1975. Those milestones illuminated the status of the transition away from burning coal, and may have marked a tipping point for renewable energy replacing all fossil fuels.17

by 2020, natural gas had replaced coal as the major fuel source for power generation in Virginia

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), Infrastructure and Regional Incentives (September 14, 2020)

renewable energy sources in the United States generated more electricity than coal for the first time in April, 2019

Source: electrtrek, Renewable energy to outpace coal for first time ever in US (April 30, 2019)

coal-based electricity generation dropped by 18% in 2019

Source: The Rhodium Group, Preliminary US Emissions Estimates for 2019

by 2022, only three power plants in Virginia were fueld by coal - Chsterfield, Clover, and Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center

Source: Enegy Information Administration, U.S. Energy Mapping System

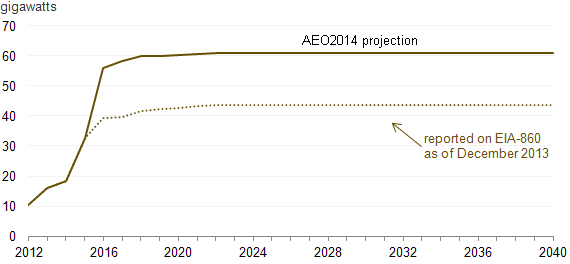

nationwide, old coal-fired power plants are being closed faster than initially predicted, rather than retrofitted before the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards for air quality go into effect in 2015

Source: Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook 2014 projects more coal-fired power plant retirements by 2016 than have been scheduled

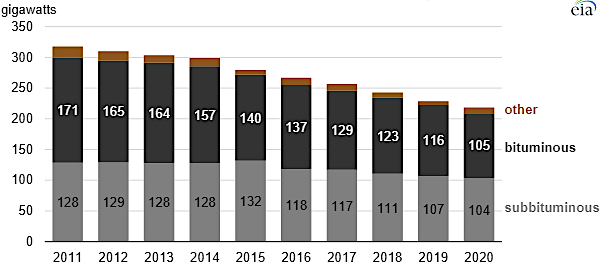

the US had 317.6 gigawatts (GW) of electricity generation fueled by coal in 2011, but plants with 88.7 GW capacity were retired by 2020

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Review 2011, 68% of U.S. coal fleet retirements since 2011 were plants fueled by bituminous coal (August 27, 2021)