Slot Machines (and Casino Gambling?) on the Maryland-Virginia Waterfront

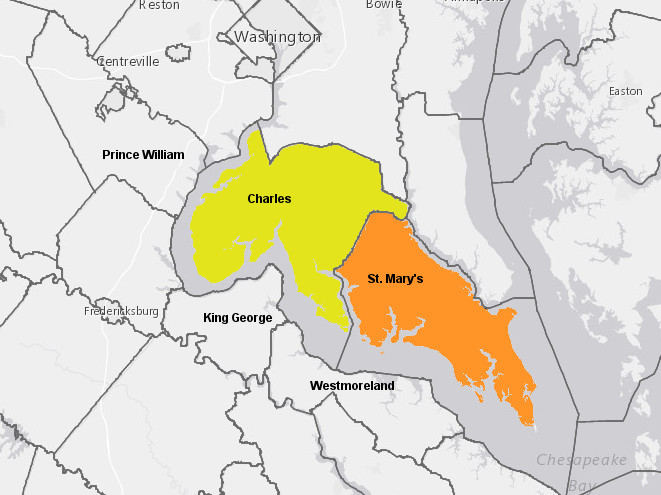

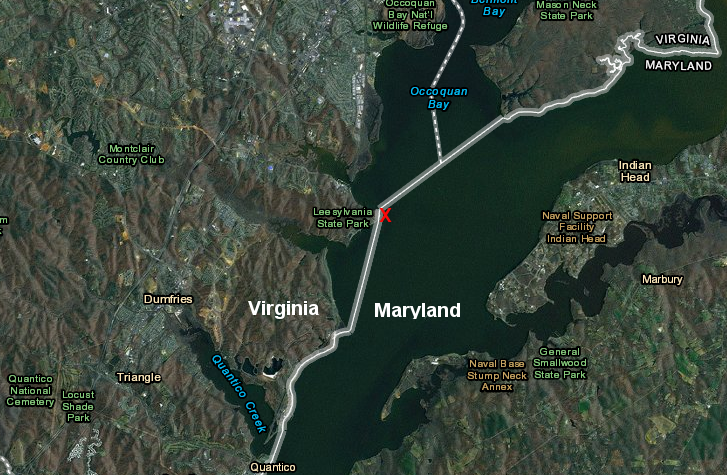

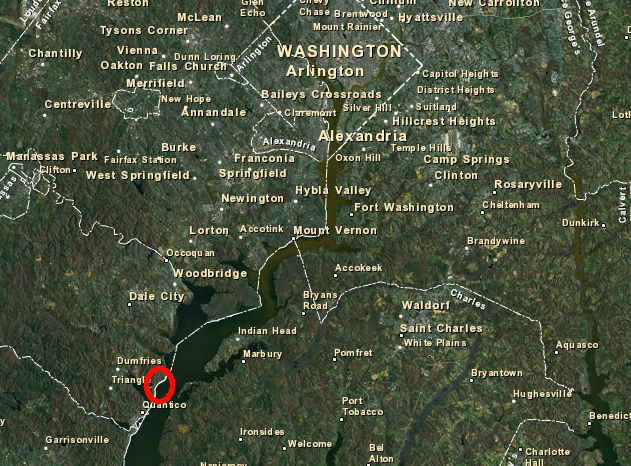

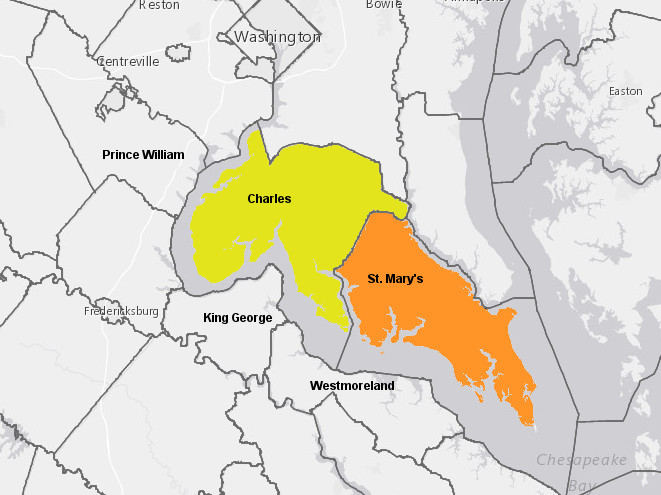

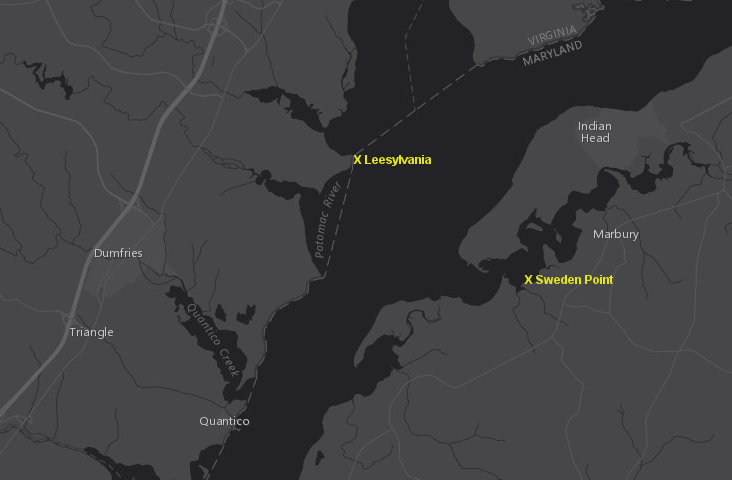

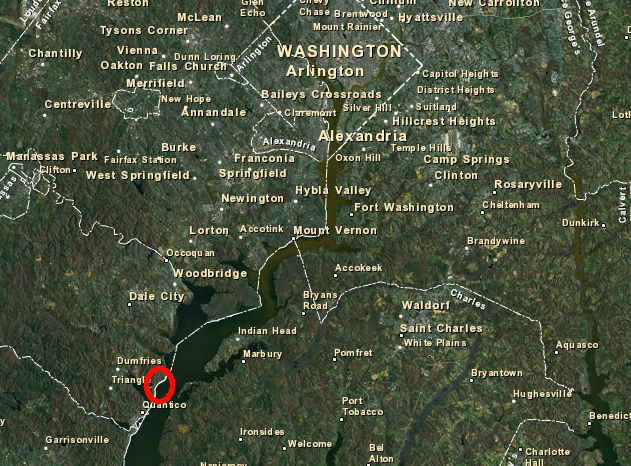

between 1949-1958, gamblers could walk from the Virginia shoreline in Prince William, King George, and Westmoreland counties to slot machine casinos in Maryland, crossing on piers beyond the low water mark of the Potomac River to reach Charles and St. Mary's counties

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

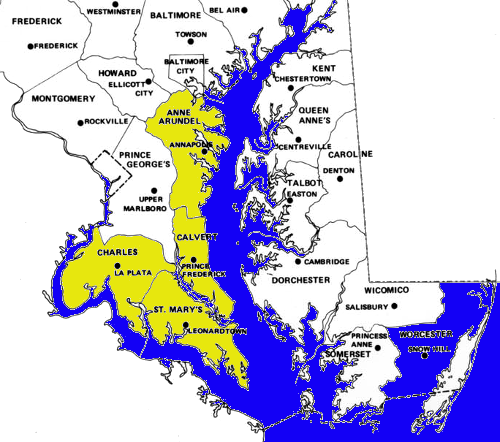

In the 20th Century, Maryland was far more relaxed about gambling than Virginia. After World War II, Maryland officials officially authorized slot machines in Charles County and St. Mary's County. That decision, plus the location of the Virginia-Maryland boundary, made it possible for Virginia gamblers to play the slot machines in Maryland without having to cross the Potomac River.

As defined in the 1632 charter to Lord Baltimore and later interpreted by Federal courts, the Virginia-Maryland boundary is at the low-water line of the Potomac River - not in the middle of the river. As a result of that location and because the two states had very different laws regarding gambling, people were able to step onto piers attached to the Virginia shoreline, walk a short distance above the Potomac River until crossing the low-water mark, and enter gambling casinos that were illegal in Virginia but approved by local officials in Charles County and St. Mary's County.

Slot machines, invented after the Civil War, were in operation in Charles County, Maryland by 1910. Officials in that state informally allowed the "amusement devices" in restaurants, bars, even doctor's offices across southern Maryland. In some cases, children waiting for the school bus would run into convenience stores and bet their lunch money; one reminiscing state legislator commented that slot machines were "everywhere except churches."

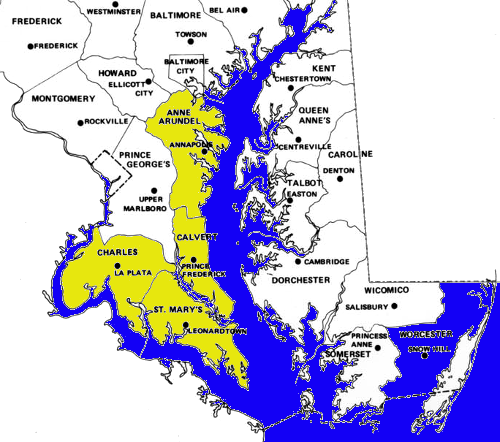

In the 1940's, state and local officials approved legislation that formally permitted slot machines in four counties, including Charles County and St. Mary's County. The governor endorsed local option, allowing for legalization by a local referendum, in exchange for support for a state sales tax. Because a Federal law (the Johnson Act) banned interstate transport of gambling equipment, those four counties ended up with a monopoly on the legal slot machine business on the East Coast after 1951.1

four counties in Maryland used local option authority to allow slot machines, until the state legislature over-ruled them and banned slots between 1968-1997

Map Source: Maryland State Archives, Map of Maryland Counties & County Seats

The Route 301 bridge across the Potomac River had opened in 1940, and the location of the Maryland-Virginia boundary made it easy for Virginia customers to access slot machines in St. Mary's and Charles counties. Slots in Maryland were legalized during the days of segregation, and black customers stayed in black-operated motels and gambled in black-operated taverns and restaurants.2

Though a car/bus trip across the Route 301 bridge was convenient, gambling operators quickly identified a way to attract customers to Maryland slot machines without requiring a trip completely across the Potomac River. Gambling barges and shacks were located at the end of piers which stretched from the Virginia shoreline into the river, barely reaching across the Maryland-Virginia border.

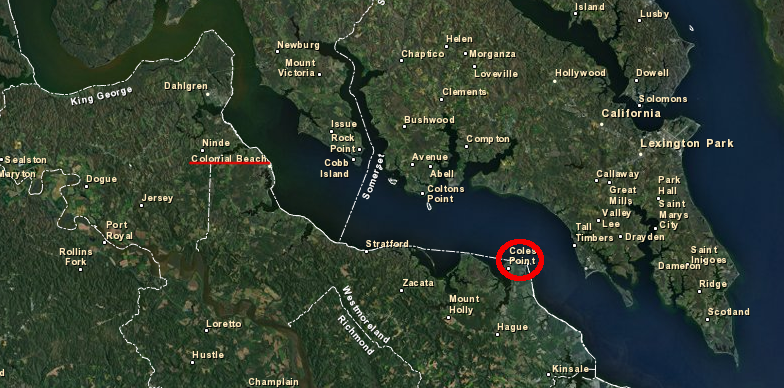

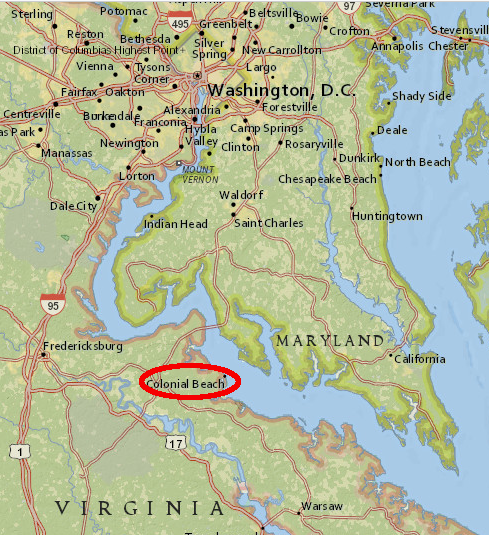

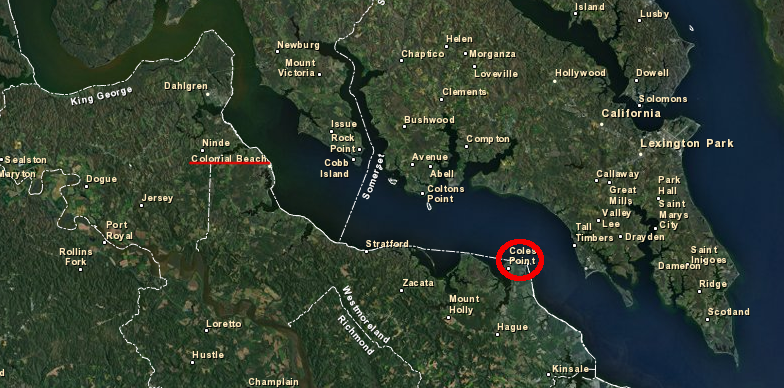

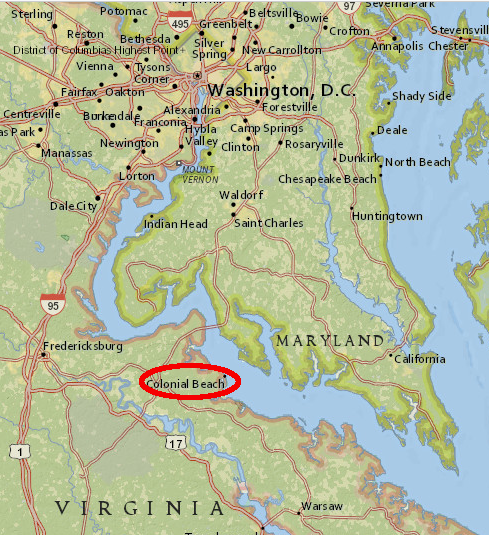

Piers in King George County at Fairview Beach, and in Prince William County at Leesylvania, were connected to gambling boats that technically were in Charles County, Maryland. There were three waterfront gambling opportunities in Westmoreland County at the Town of Colonial Beach, Muse's Beach at the mouth of Pope's Creek, and at Coles Point.

the opportunity to gamble at Colonial Beach, on a pier extending into Maryland, was highlighted in a pre-World War II postcard

Source: Boston Public Library, In Colonial Beach it's Monte Carlo for amusements and the Surf Room for dancing and cocktails

The Coles Point Tavern in Westmoreland County was licensed by St. Mary's County. All other waterfront gambling operations with piers connected to the Virginia shoreline were licensed by Charles County officials. In addition to the entertainment of slot machines, the Maryland establishments offered liquor by the drink, which was also against the law in Virginia.3

Five casinos operated at Colonial Beach, the Little Reno, Jackpot, Monte Carlo, New Atlanta, and Little Steel Pier. Guy Lombardo once attracted crowds to the Reno, which had a large dance floor in addition to over 300 slot machines. Slot machines were delivered by boat, staying within Maryland rather than using Virginia roads, to avoid violating the Johnson Act.

When high waves generated by Hurricane Hazel threatened a pier at Colonial Beach in 1954, the valuable machines could not be brought onshore for fear of confiscation by Virginia authorities. Instead, the slot machines were lowered by rope and pulley to another casino nearby, though three of them broke loose and were lost. The pier collapsed just half an hour after the salvage operation was completed.4

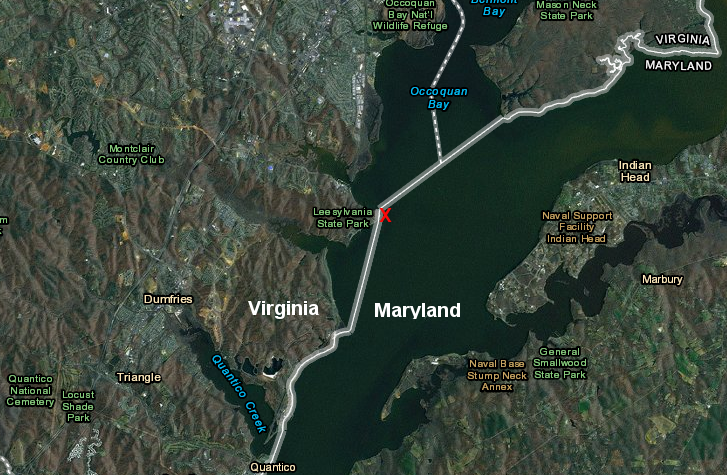

Plans to anchor three gambling barges just offshore from Gunston Hall and establish the "Gunston Hall Yacht Club" were blocked. Opposition may have been successful in part because Clyde Tolson, the close confidant of Federal Bureau of Investigation director J. Edgar Hoover, lived near Gunston Hall. A pier was built in Prince William County at Leesylvania and a slot machine facility opened there, rather than at Gunston Hall.5

Owners of establishments with slot machines were closely connected to Maryland state officials, and bribery may have been a factor. One Maryland legislator who was given complimentary coins on a familiarization tour of casino at Colonial Beach chose put them into his pockets, rather than use the coins in the slot machines. When he slipped, people nearby:6

- ...grabbed his arms, [but] he had so much weight in his pockets that his suspenders broke. And his trousers came down.

Westmoreland County offered two opportunities, at Coles Point and Colonial Beach, for Virginia gamblers to walk across the border into Maryland

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

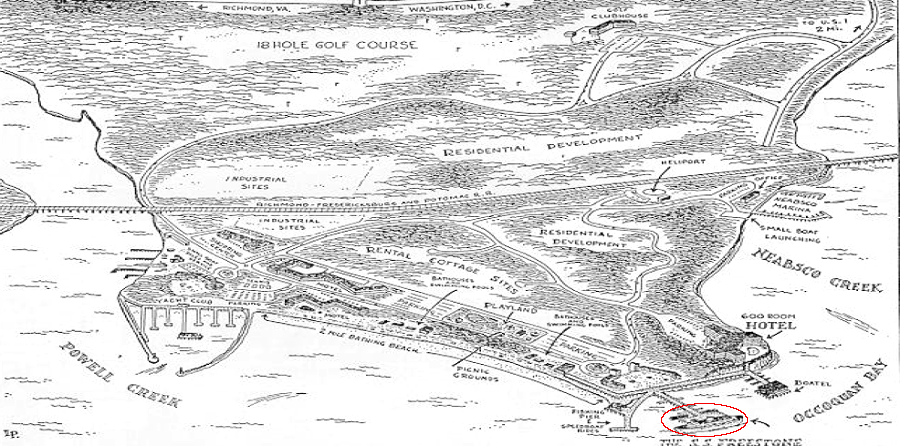

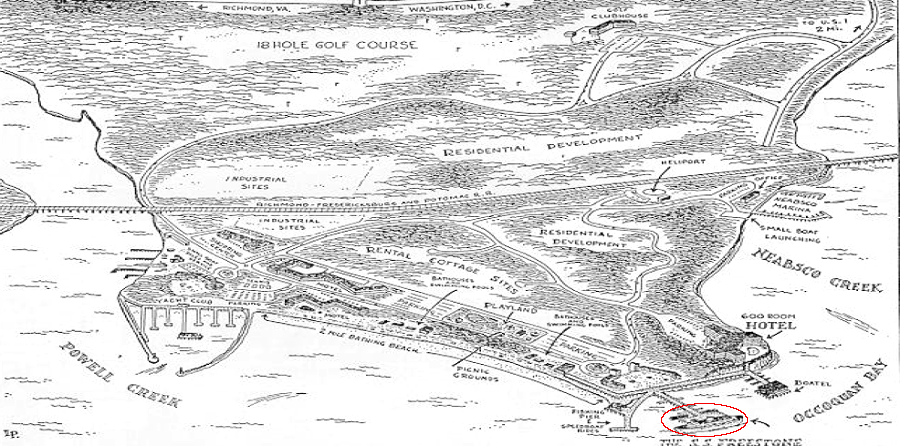

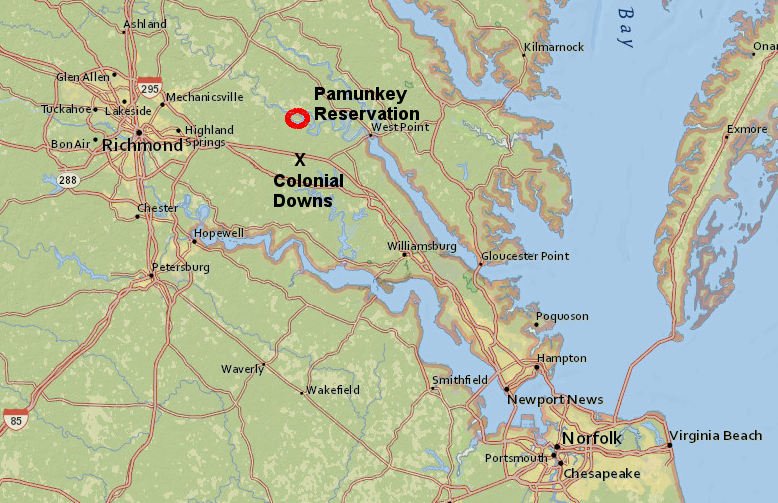

In Prince William County, the SS Freestone (built in 1910 as a passenger steamer and originally called City of Philadelphia) was docked at Freestone Point on the old Leesylvania plantation. Customers walked on a short pier from Freestone Point to the ship, which was far enough offshore to be located in Charles County, Maryland. Plans to develop the peninsula at Leesylvania into a family amusement resort were publicized, but the main investment was in the gambling operation for adults.

Carl Hill's plans for developing the Leesylvania peninsula as the Pleasureland of the East included more than just the SS Freestone gambling boat

Source: Prince William County, The History of the Prince William County Waterfront

The gambling boat offered liquor-by-the-drink as well as 200 slot machines in 1957-58. The SS Freestone created tax revenue for Charles County in Maryland rather than for Prince William County in Virginia, but attracting as many as 15,000 customers on weekends did create jobs - including two teams of people hired to provide security, one authorized to enforce Maryland law on the boat and a separate team to enforce Virginia law on the land.

When the Prince William Board of County Supervisors asked the Maryland legislature to change the law authorizing offshore gambling, the elected supervisor representing the Freestone Point area (Dr. A. J. Ferlazzo) supported the gambling boat.7

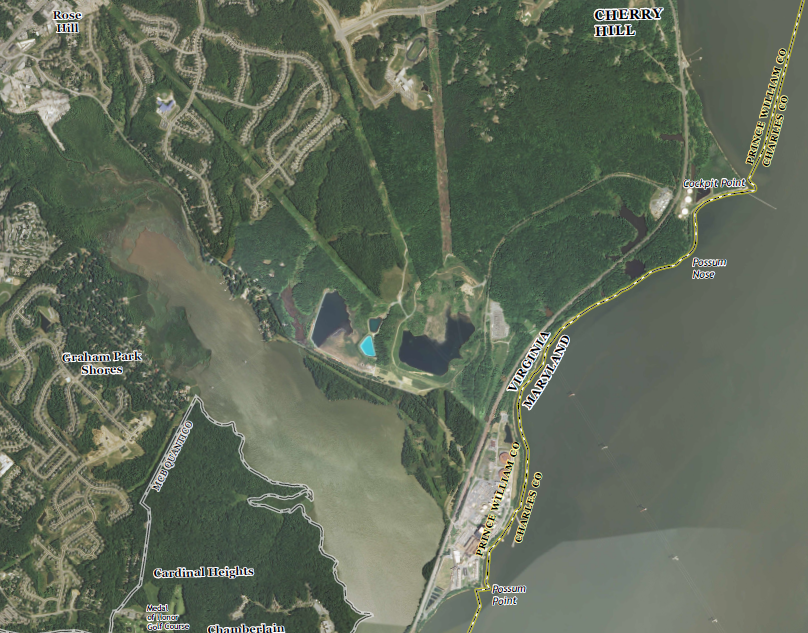

the SS Freestone (red X) was docked at what is today Leesylvania State Park, upstream (north) of the Potomac Shores development on Cherry Hill Peninsula

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Saturday Evening Post highlighted Colonial Beach as "Las Vegas on the Potomac" in 1957. Westmoreland County, which had a population of less than 11,000 people in 1950, had 20,000 people per weekend coming to the casinos at Colonial Beach. The magazine noted how one major operator there, Del Conner, expanded his hotel business to take advantage of the boundary created by King Charles I in his 1632 land grant to Lord Calvert:8

- Conner owes his enviable position to a highly developed sense of geographical values. Virginia laws ban both gambling and drinking hard liquor in public. Yet Conner is immune from prosecution; his casinos operate openly in the protective presence of uniformed deputy sheriffs. What explains the paradox is a freakish state border. Technically, the piers fall within the jurisdiction of Charles County, Maryland, even though the Maryland mainland begins six miles away, on the other side of the Potomac...

- ...Thanks to whimsical King Charles I, Conner and his colleagues were no more subject to Virginia restraints than the lords of Las Vegas.

Virginia officials complained regularly to Maryland's governor and other leaders that the gambling boats were a public nuisance. Moral objections were raised by ministers, and there was a persistent perception that slot machine businesses were bribing local officials. The cash operations were seen as potential money laundering vehicles for criminal enterprises. Maryland officials also feared that the Patuxent River Naval Air Station might not expand if the slot machines remained available.

At the same time Virginia and Maryland were negotiating an update of the Compact of 1785 regarding control of oyster harvesting and other activities on the Potomac River, the Maryland legislature changed its laws allowing riverfront casinos. At the end of October, 1958, customers were required to access the gambling boats from land in Maryland. Simply crossing over the Maryland-Virginia boundary on a gangplank was no longer legitimate.

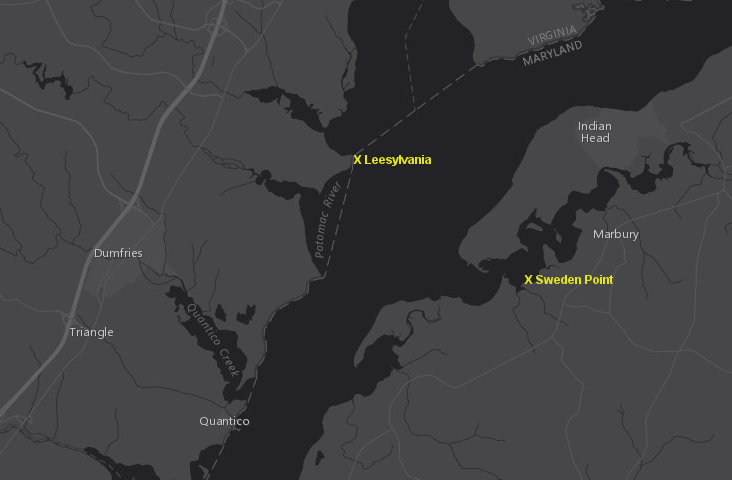

Blocking Virginia customers from walking directly onto the boats ended the borderline gambling tradition. The SS Freestone was renamed the SS Potomac and finished her working days on the Hudson River. The owner, Carl Hill, moved his gambling operation to the Maryland shore at Mattawoman Creek. He used a boat to carry customers from the old Leesylvania site across the Potomac River to his new crab house and casino at Sweden Point.9

in 1958 Maryland required customers to access gambling facilities from land in Maryland, so the SS Freestone operation at Leesylvania was closed and boats carried Virginia customers across the Potomac River to a new slot machine casino/restaurant at Sweden Point (now Smallwood State Park)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Opposition to the remaining gambling operations in Maryland continued, and by 1968 all the legal slot machine businesses in Maryland had been phased out. The tradition of borderline gambling on the Potomac River was slow to fade away, however, despite the changes in state laws.

As late as 1979, the Coles Point Tavern was raided by Maryland State Police. They took a boat across the river, found gambling equipment, and arrested the owner. It was, of course, no secret to the Virginia customers that the shack, self-described as a "weather beaten bar that has been in St. Mary's County, Maryland, since 1953 when it was constructed on pilings over the Potomac River" offered entertainment that was not readily available elsewhere in Virginia. As Captain Renault said when closing down Ricks Bar in the movie Casablanca, "I'm shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in here...")10

whether or not the Coles Point Tavern is located in Maryland or Virginia, slot machines are no longer legal there

Source: Google Mapper

Gambling returned to Colonial Beach after the Maryland Lottery started in 1976. Until the Virginia lottery started in 1988, the busiest Maryland Lottery terminals were on The Riverboat at the end of a pier which extended far enough into the Potomac River so it was in Charles County, Maryland. That building was the last of the old riverfront casinos, once known as the Little Reno.

The Riverboat today is a replacement, built after Hurricane Isabel in 2003 destroyed the previous version. It now provides a place for customers to buy a Virginia Lottery ticket, then step a few feet across the border and purchase a Maryland Lottery ticket. Once across the state line, people can bet in a Maryland Off Track Betting (OTB) parlor, play keno, and occasionally join a "Texas Hold 'em" tournament.11

In 2008, Maryland legalized slot machines again, allowing gambling at five casinos. Virginia officials feared the potential for expansion beyond those five locations, and a return of waterfront gambling operations. The Virginia House of Delegates asked Maryland to "refrain from authorizing... gambling in or on the shores of the Potomac River."

The sponsor of the Virginia resolution was motivated by moral objections to gambling. He also acknowledged that the economics of shoreline gambling benefited Maryland far more than Virginia when he commented:12

- They get the money, we get the problems.

In 2012, Maryland voters authorized a sixth casino (at National Harbor, on the Maryland side of the river opposite Alexandria) and expanded gambling operations to include poker, craps and roulette. The opening of casinos in Maryland have impacted business at the West Virginia and Delaware gambling centers. Charles Town in West Virginia used to be the closest place for DC-area residents to gamble legally, and 50% of the business in Delaware's casinos came from Maryland residents. As the Delaware Lottery director noted:13

- You'll need a pretty good excuse to drive past a Maryland casino to come to one of ours now... It used to be just us and Atlantic City, but we have a proximity problem now. We couldn't have the monopoly forever.

Thanks to Maryland's expansion of gambling, Northern Virginians no longer needed to drive to Atlantic City or to the racetrack at Charlestown, West Virginia. Virginians could cross the Woodrow Wilson Bridge to gamble at casinos in Maryland along the I-95 corridor.

Most gamblers in Maryland lived within 30 minutes of a casino, though the sixth casino in Maryland at National Harbor in Prince George's County drew as much as 20% of its customers from tourists visiting DC. That casino also attracted Virginia residents, which Maryland relied upon when assessing where it should authorize its sixth casino:14

- ...the new casino in Prince George's County, at any of the three locations proposed, will be the most conveniently-accessible casino for most of the population of Virginia.

At the time the casino was approved in National Harbor, Virginia politicians expressed strong moral reasons when discussing their opposition to casinos. However, the state had a long history of support for gambling.

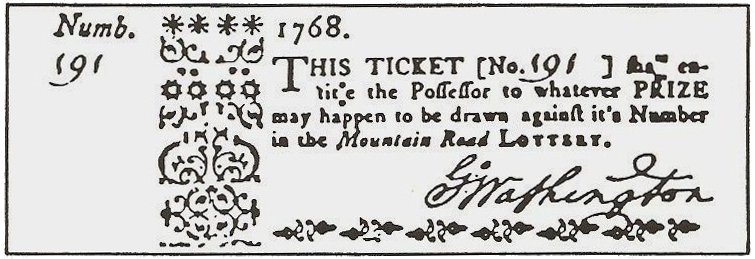

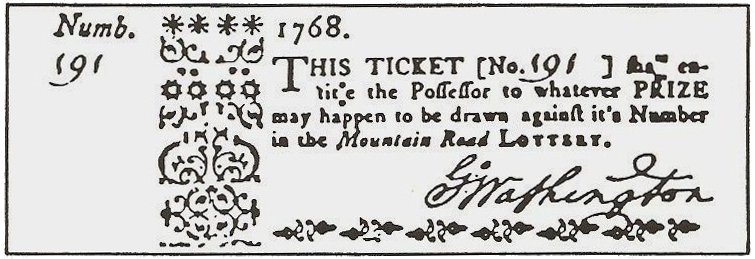

The Virginia Company of London, which financed the settlement at Jamestown and initial colonization efforts, used a lottery in 1612 to raise funds from English gamblers for the venture. In 1767, George Washington sponsored the Mountain Road Lottery to build a road to what today is the Homestead Resort, but it failed to sell enough tickets because there were so many other lotteries occurring at the same time. King George III finally banned new lotteries in 1769.15

George Washington took dramatic gambles throughout his life, from traveling to confront the French near Lake Erie in 1753 to starting a distillery in 1797, but his plan to using finance a road through the Allegheny Mountains failed because there were too many competing lotteries

Source: Mountain Road Lottery: Setting the Record Straight by Ron Shelley

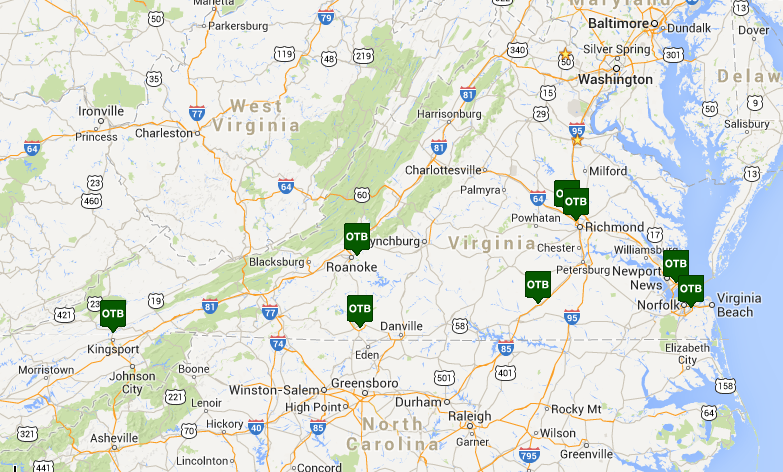

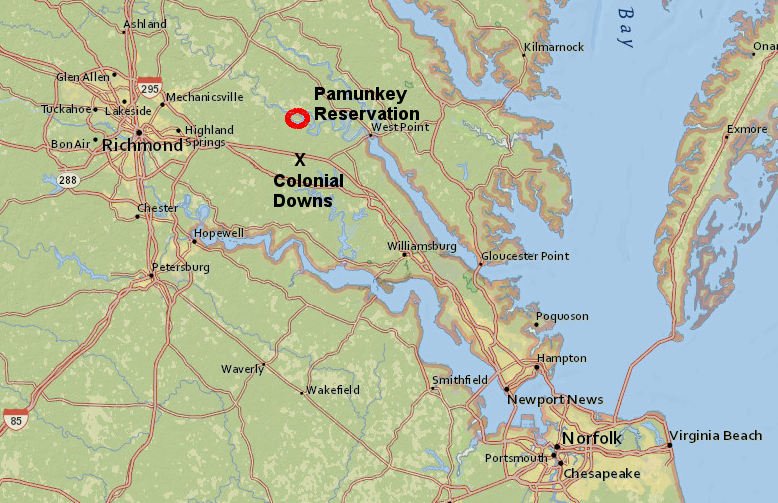

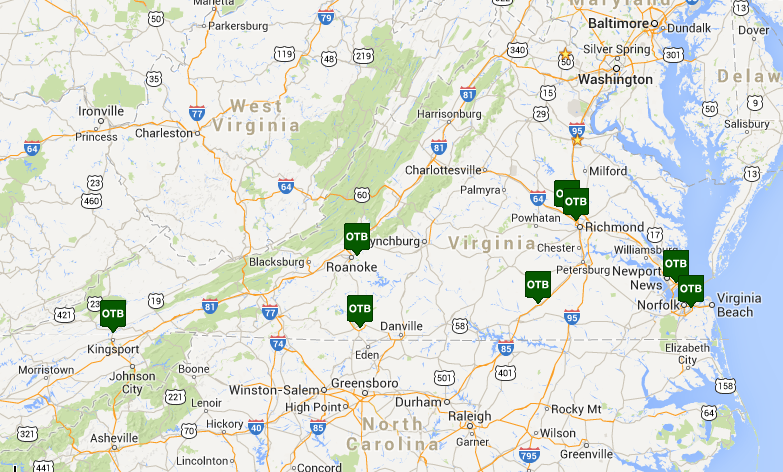

Virginia's General Assembly broadened legal gambling beyond bingo parlors, authorizing a state lottery in 1988 and then allowing bets on horse races starting in 1997. The Virginia Racing Commission licensed year-round pari-mutuel gambling at the Colonial Downs racetrack between Richmond and Hampton Roads, while steeplechase races such as the Gold Cup in Fauquier County and thoroughbred races at Morven Park near Leesburg receive short-term gambling licenses. When the Colonial Downs racetrack was open (it closed in 2014), there were off-track betting (OTB) parlors plus many more kiosks scattered across Virginia for online pari-mutuel betting on out-of-state tracks.

State and Colonial Downs racetrack officials clearly understood the advantages of drawing customers across state lines to off-track betting parlors in order to increase business and tax revenues. Two of the initial Virginia OTB parlors were approved near North Carolina in Alberta (on I-81) and Ridgeway (on US 220, near US 29), plus one near Tennessee in Weber City in Scott County (on US 23, near I-81).

off-track betting parlors in Virginia are located to meet customer demand in the urban areas - but locations in Alberta, Ridgeway, and Weber City are designed to pull customers across the North Carolina/Tennessee borders

Source: Colonial Downs, Colonial Downs OTB Locations

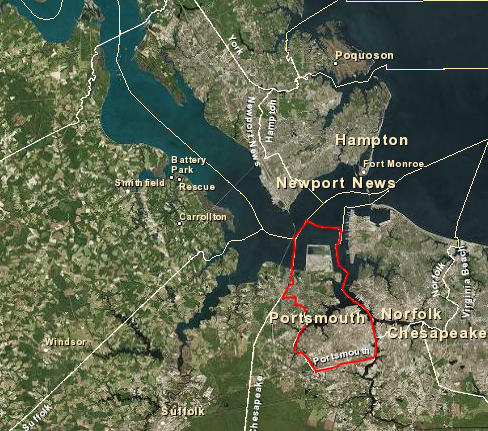

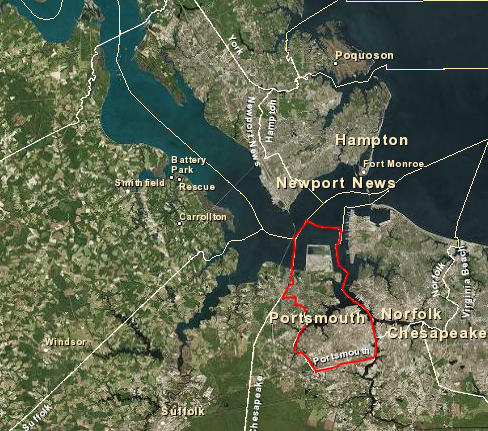

Customers from Virginia traveled to casinos in other states in the region, starting with Atlantic City (New Jersey) in 1978. Legislators from Hampton Roads proposed several times that a casino located in Virginia would retain gambling revenues within the state, generating funds needed for new transportation projects and to reduce existing bridge tolls in the Hampton Roads region.

In 2013, the Virginia State Senate finally authorized the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization to study casino gambling opportunities in Virginia. The report identified studies that predicted 45% of people living within 30 minutes of a casino would gamble, and that 12% of Virginians gambled in 2003 by traveling to casinos in Atlantic City and Las Vegas. The optimistic assumption in the study was that tax revenues would exceed $100 million annually if a casino was authorized, in large part because:16

- In the event that a casino was built and operated in Hampton Roads, a large number of those trips would likely be redirected to the local casino.

-

- ...the propensity to gamble increases with proximity to a casino, and the vast majority of the increased gambling occurs locally.

Portsmouth is the jurisdiction in Virginia most interested in a casino or riverboat gambling

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2015 the Portsmouth City Council asked the state to allow a casino. The City Council proposed to limit where the casino would be located by asking that use revenues be used just to reduce tolls on the Downtown and Midtown tunnels, and to help finance the Dominion Boulevard widening and the Martin Luther King Freeway Extension. The State Senator from that area had previously requested state authorization of a casino or riverboat gambling to finance transportation projects in the Hampton Roads region and spur development in that economically-depressed city, claiming Virginians spend $1.5-$2 billion annually at out-of-state casinos.17

The economic assumptions in the 2013 study by the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization were questioned in "The State of the Region - Hampton Roads 2015" report from Old Dominion University. Though a casino might retain some revenue currently being spent by Virginia gamblers at out-of-state casinos, the primary advantage would come from drawing customers from the Carolinas (where legal casino gambling opportunities are limited) to Hampton Roads:18

- If a dollar spent at the casino represented one dollar less spent at the Patrick Henry Mall, or at the Virginia Beach oceanfront, then there would be no net new tax collections at all. The key, then, would be to attract gamblers from outside of Hampton Roads.

In 2014, a riverboat gambling bill finally received approval by a key committee in the State Senate, but the bill died before passage. By then 40 states had authorized casino gambling, but Virginia legislators chose to remain one of the 10 states who did not.

the Portsmouth equivalent of the Colorado Belle (on the Colorado River at Laughlin, Nevada) could be named after the Elizabeth River

Source: Wikipedia, Colorado Belle

Until 2019, the Virginia legislature refused to authorize even a public referendum on riverboat gambling, which could lead to "dens of iniquity" casinos with poker, blackjack, and slot machines that compete with Maryland or West Virginia casinos. The State Senate's Democratic leader in 2014 assessed the potential of final approval of casino gambling in Virginia as very low, saying:19

- The only question about casino gambling is who will be the 50th state to get it - us or Utah... Forty-nine states will have it before we get it...

- ...You can bet that at that casino across the river [MGM's casino at National Harbor in Maryland], probably a third to 50 percent of their revenue is gonna come from Virginia. They'll be raking in a fortune before it dawns on us that we should have done that a long time ago. It's money that could have stayed in Virginia, but once again we'll be left out in the cold.

In 2017, the General Assembly again rejected Portsmouth's proposal to authorize a casino in Virginia, describing the attraction of Maryland casinos as creating a "huge sucking sound." MGM officials indicated half of their customers at the National Harbor casino that opened in 2017 were coming from Virginia.

The Virginia Lottery officials estimated that lottery's annual profit of $550 million was reduced by $10 million due to the casinos across the Potomac River, and suggested that the Virginia Lottery was the appropriate state agency to oversee casino gambling if it was allowed.20

MGM demonstrated that it is concerned about a competing casino being authorized in Virginia. One possibility the company has considered is the potential for the Pamunkey Tribe to open a casino between Richmond and Hampton Roads. In 2014, the MGM corporation formally objected to Federal recognition of that tribe.21

In 2015, the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the US Department of the Interior rejected concerns expressed by MGM and others, and granted Federal recognition. Such recognition acknowledged that the Pamunkey Tribe had been in continued existence and had not disappeared in the 408 years since English colonists arrived at Jamestown. On a more practical level, formal recognition expanded the tribe's access to Federal programs designed to enhance social and economic opportunity.

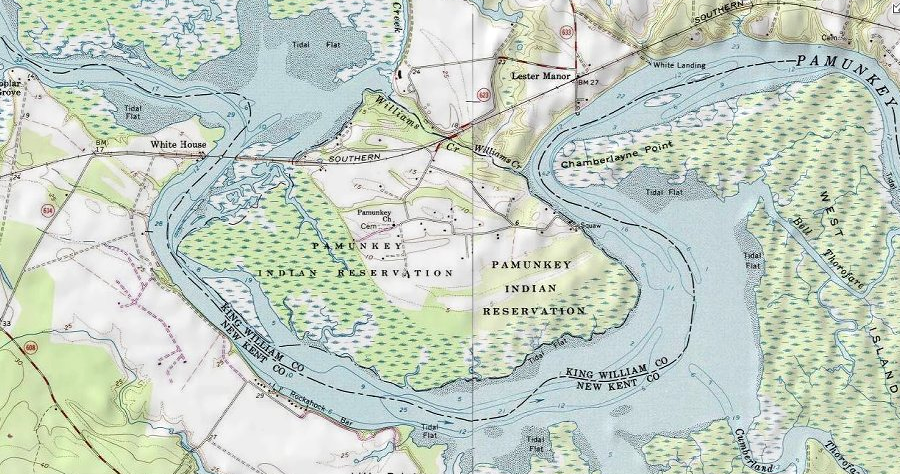

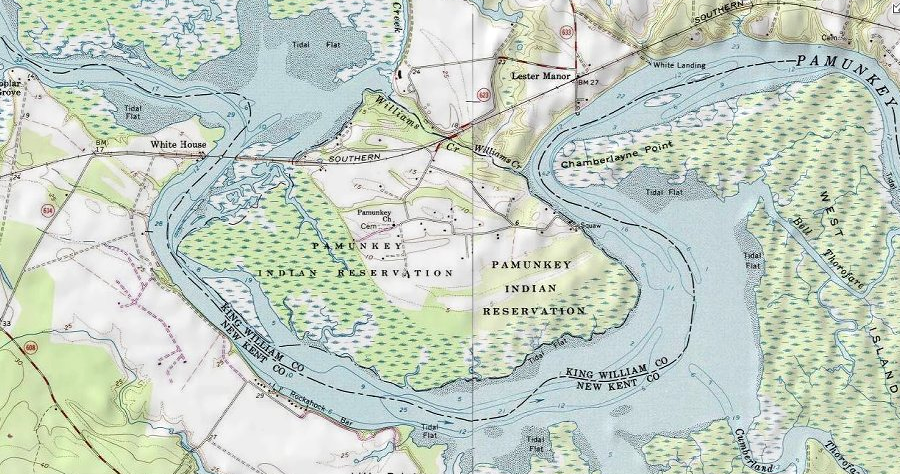

Federal recognition in 2016 did not convert the Pamunkey Reservation in King William County into a Federally-protected reservation, or authorize casino gambling on the tribe's reservation in King William County. Creating a casino on the reservation would very difficult; under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, the approval of Virginia's elected officials is still required.

the Pamunkey Indian Reservation is on the north bank of the Pamunkey River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

There is no Federal treaty with the Pamunkey Tribe creating a reservation guaranteeing certain rights. Ratification of the US Constitution and creation of the Federal government did not occur until 1788, over 100 years after the Anglo-Powhatan wars concluded with treaties signed by Virginia's colonial government and remnants of the Native American tribes in Tidewater.

Because there was no Federal treaty with the Pamunkey Tribe, there were no treaty-based guarantees between the US Government and the tribe that would authorize casino-style gambling on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation until 2015.

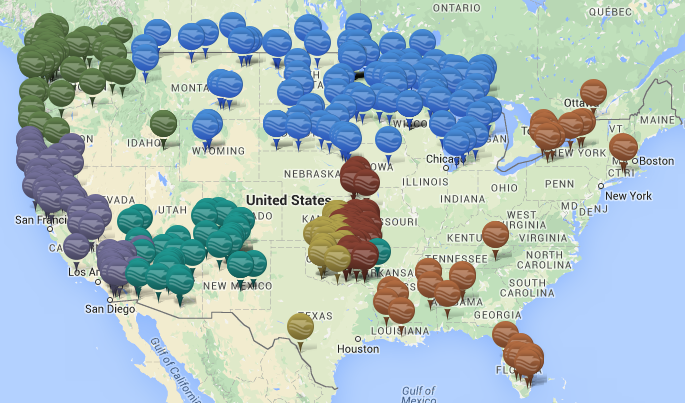

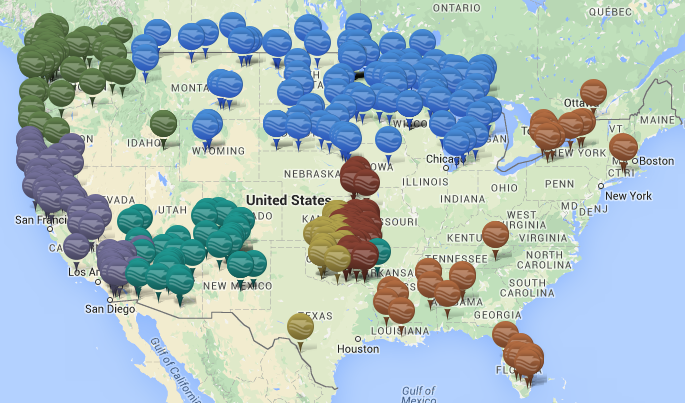

The tribe had the option to seek authorization for limited gaming operations using procedures based on the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. That Federal law was passed by the US Congress in 1988, after the US Supreme Court ruled in California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians that states lacked authority to block casinos on reservations held "in trust" for Federally-recognized tribes. By 2015, when the Pamunkey were recognized, over 40% of the Federally-recognized tribes operated casinos and gaming facilities in 28 states.

In 2018 the Pamunkey announced plans for a $700 million gaming facility to be constructed in partnership with an investor group. Details regarding the gaming operations were not specified, though the tribe indicated a site would be chosen away from the reservation. An investor working with the Pamunkey purchased land on I-64 near the Colonial Downs racetrack.

the National Indian Gaming Commission regulates gaming operations in over half of the states, but the closest to Virginia is in Cherokee North Carolina

Source: National Indian Gaming Commission, Map of Indian Gaming Locations

Tribes seeking to open casinos with roulette wheels, slot machines, and card games such as blackjack where gamblers bet against the house must get state concurrence. The Pamunkey Tribe could have opened a casino without state approval, but only if the Federal government decided to treat the Pamunkey's 1,200-acre state reservation as a Federal reservation. New legislation by the US Congress might be required before the Bureau of Indian Affairs could accept the reservation "in trust" for the tribe, or to accept land closer to I-64 "in trust."

Assuming the Pamunkey reservation status shifted from just state-recognized to Federal-recognized, the tribe still could not offer what the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act categorizes as Class III gaming (slots, blackjack, roulette, horse racing, or lotteries) unless the tribe negotiated an agreement with the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Such tribal-state compacts define how revenues will be shared, and require approval by state legislatures before the National Indian Gaming Commission will regulate them. The US Supreme Court has ruled that states can simply refuse to negotiate a Class III gaming compact with a tribe, so Virginia officials could demand an unacceptable share of the revenue as a condition of signing a compact. The hostility of the Virginia General Assembly to casinos could remain a barrier that only another act of Congress could overcome.

The Pamunkey tribe could have initiated a Class II gaming operation - essentially bingo games - with approval from just the National Indian Gaming Commission. Technology now allows that bingo experience to resemble the atmosphere of a casino, but a Class II facility would lack the table games available in Maryland casinos after 2012.22

Beyond the difficult legal and political hurdles, if the Pamunkey tribe decided to start a gambling operation on the isolated reservation, it would have to attract customers. Drivers must spend 45-60 minutes on narrow roads from I-95 at Richmond or I-64 at Williamsburg to reach the reservation.

The Colonial Downs horse track in New Kent County, built for $45 million on I-64 between the urban centers of Richmond and Norfolk/Virginia Beach, was much easier to access. Colonial Downs stopped offering horse races and closed its gambling facilities in 2014 because profits were insufficient, suggesting that demand for gambling further off the interstate at the reservation would be limited.

if Colonial Downs could not succeed, how could the Pamunkey Reservation attract enough customers to justify even a Class II gambling operation based on bingo?

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

MGM had opposed the Federal recognition of the Pamunkey tribe, fearing potential competition in the long run.

The Pamunkey could have used their unique status as a Federally-recognized tribe and found a political path to re-open the Colonial Downs facility as a casino with more gambling choices than just horses. For example, Congress could have passed a version of the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act that pre-empted state objections.

MGM had legitimate reasons to fear competition from the tribe. In 2015, Pamunkey leaders explored the potential to open a casino operation. They proposed a budget that would dramatically increase the pay of the tribe's chief and council members using revenue to be provided by outside supporters of the casino. Those leaders were replaced in the next tribal election and Maryland avoided competition for the moment. In 2018, however, the Pamunkey announced plans for a $700 million resort, with casino and hotel.23

Actions by the tribe cracked the long-standing resistance of the General Assembly to casino gambling. The Pamunkey were poised to become the only provider of full-scale gambling in Virginia. Like tribal officials, leaders in Portsmouth and other economically-stressed cities saw the opportunity to get new revenue from new casino resorts.

The General Assembly authorized slots-like gaming machines at Colonial Downs in 2018, to incentivize the purchase and re-opening of the track by Revolutionary Racing. That deal was separate from the Pamunkey's efforts to open a $700 million gaming facility in partnership with investors, announced in 2018 after the tribe had received Federal recognition.24

Projected revenues and jobs claimed for a casino rarely acknowledge that existing revenues and jobs will be decreased. If people living near the casino divert their spending, buying less at local stores while spending more at a casino, then revenues and employment at local stores will decline and offset the gains from a casino.

The net economic benefits of a gambling operation on I-64 east of Richmond would be based on the ability to attract out-of-state customers, or to keep Virginians from taking their money to out-of-state casinos. As a 2015 study of potential gambling in Hampton Roads noted:25

- If a riverboat casino were to open, say, on the Elizabeth River in the middle of Hampton Roads, it would have only a small economic impact on our region. This is because casino expenditures usually reduce other expenditures. Only if the casino attracted gamblers from outside Hampton Roads, or if it acted as a magnet so that our residents stopped spending money outside our region, would there be any economic impact of note.

The Virginia General Assembly approved casino gambling in Virginia in 2019, but did not authorize any locality north of Richmond to approve a casino. One option is that history could repeat itself, and Maryland could approve waterfront gambling boats again on the Potomac River. Inviting Virginia customers to walk a few steps on a gangplank to cross the border, in order to gamble on a ship docked technically in Maryland's Potomac River, would not be a new tactic.

Until a Virginia casino opens near the Potomac River, Maryland gambling companies will rely more heavily upon customers from Northern Virginia. Since Maryland authorized casino gambling in 2008 and expanded table gaming in 2012, state-permitted casinos have quickly saturated the market along I-95 to compete with gambling opportunities offered in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Delaware, and New Jersey. The last casino to be constructed, MGM National Harbor, predicted that 70% of its customers would be non-Maryland residents.26

In 2014, four casinos closed in Atlantic City, leaving only eight still in operation. Maryland's market opportunity is to the south, where there is less competition.27

Maryland expanded casino gambling in 2012 beyond slot machines to offer table games such as poker

Source: Library of Congress, Slot machine arcade at the Tropicana Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada

By 2015, there was just one under-served market feeding customers to Maryland: Virginia, especially south of Fairfax County from Lorton to Richmond. Many potential customers could be interested in entertainment that includes gambling, but reluctant to drive through congested Northern Virginia traffic to reach Maryland's existing casinos. That creates one more opportunity for Maryland to expand its gambling operations, by authorizing a new gambling riverboat docked near the Virginia shoreline.

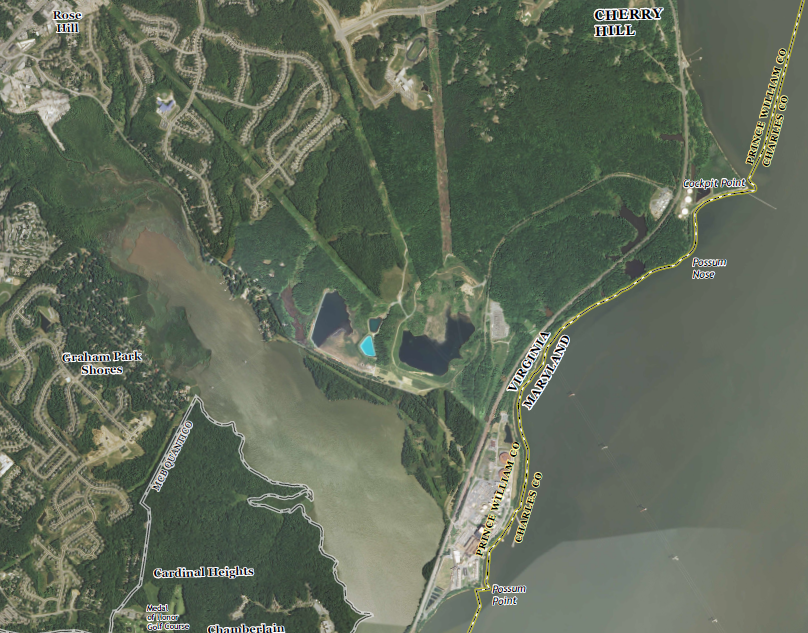

The number of suitable locations for such boundary-based riverboats is limited. The boundary line between Maryland and Virginia does not follow the low-water mark of the Potomac River exactly. The boundary often cuts across bays, from headland to headland, leaving Virginia with portions of the river. Often the Virginia shoreline is too far from the legal Maryland-Virginia border for customers to walk on a pier to a riverboat in Maryland.

South of Leesylvania State Park, however, is the Cherry Hill Peninsula. The proposal to develop that area into the Potomac Shores community includes plans for a town center at the tip of the peninsula. Anyone living there would experience a long drive just to get to I-95, in order to commute to any job not located near a Virginia Railway Express (VRE) station. However, if a Maryland gambling operator offered economic incentives for the Potomac Shores development in Virginia, then a riverboat casino next to the Virginia border could become realistic.

Similarly, the Town of Quantico struggles to generate sufficient tax revenue to redevelop. The town is surrounded by the Quantico Marine Corps Base, but remains an independent jurisdiction. In theory at least, it could build a pier extending into the Potomac River in exchange for a share of the revenues that a modern SS Freestone could generate - though the Marines would surely object.

If the Maryland General Assembly wanted a revenue boost by authorizing another casino, MGM or another licensee could open a border-of-Virginia casino without any approval from the Virginia General Assembly. A casino at the Cherry Hill Peninsula, or at Quantico, would be far closer to the Northern Virginia market than a casino planned by the Pamunkey Tribe or the Colonial Downs racetrack on I-64 in King William County.

One other potential source of competition for MGM: the District of Columbia could authorize gambling. A 2004 effort to legalize 3,500 slot machines in Anacostia failed and there were systemic violations of election laws during the effort to get signatures on the petitions. A 2006 initiative also failed, but the same real estate and gambling entrepreneur tried again in 2016. A casino in DC could be visited by the tourists that MGM wants to attract to its casino at National Harbor, and potential draw away some Virginia residents.28

The operator of the Colonial Downs racetrack identified a more realistic option. It opened a Rosies off-track betting parlor in Dumfries, then proposed building a major resort in the financially-stressed town based on gaming. The only remaining hurdle to a Northern Virginia casino became getting authorization from the General Assembly for that gaming resort to become a full-scale casino.

the Maryland-Virginia border comes close to the shoreline from Cockpit Point to Quantico, so gamblers at Potomac Shores (or Quantico) could walk on a short pier from the Virginia shoreline into a casino riverboat located in Maryland

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Quantico 7.5 x 7.5 quadrangle map (Revision 1, 2013)

Links

the Potomac Shores development on Cherry Hill Peninsula is one possible location for a riverboat gambling parlor, next to Virginia customers but licensed under Maryland laws

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

References

1.Susan Hickey Shaffer, "Slot Machines in Charles County, Maryland: 1910-1968," University of Maryland masters thesis, 1983, p.1, p.17, p.20, p.22, http://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/16861; "A look at the history of gambling in Southern Maryland," The Enterprise, October 21, 2015, http://www.somdnews.com/independent/news/local/a-look-at-the-history-of-gambling-in-southern-maryland/article_ac5d6f4c-229b-5b7d-b761-782b04a56acf.html (last checked November 1, 2015)

2. "Harry W. Nice Memorial Bridge (US 301)," Maryland Transportation Authority, http://www.mdta.maryland.gov/Toll_Facilities/HWN.html; Susan Hickey Shaffer, "Slot Machines in Charles County, Maryland: 1910-1968," University of Maryland masters thesis, 1983, p.43, http://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/16861 (last checked November 1, 2015)

3. "Slots on Piers Evade Law In Virginia: Slots on Potomac Piers Evade Virginia Law Slots 'Invade' Virginia Town," Washington Post, July 23, 1949, p.1; "Maryland's Slot Machines Operating Off Va. Beaches," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, July 22, 1949, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19490722&id=_stNAAAAIBAJ&sjid=RYoDAAAAIBAJ&pg=5457,2038446&hl=en (last checked November 1, 2015)

4. "Las Vegas on the Potomac," Saturday Evening Post, September 7, 1957, pp.87-90; "Rollin' on the river," The Gazette (Prince George's County, Maryland), May 31, 2002, http://ww2.gazette.net/gazette_archive/2002/200222/weekend/a_section/107115-1.html (last checked November 2, 2015)

5. Susan Hickey Shaffer, "Slot Machines in Charles County, Maryland: 1910-1968," University of Maryland masters thesis, 1983, pp.53-56, http://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/16861 (last checked November 1, 2015)

6. "Southern Md. areas that had slots are torn over new proposals, too," Baltimore Sun, January 26, 2003, http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2003-01-26/news/0301260205_1_slot-machines-southern-maryland-waldorf (last checked October 31, 2015)

7. Greg H. Williams, World War II U.S. Navy Vessels in Private Hands, 2013, p.151, https://books.google.com/books?id=1zmNAgAAQBAJ; "Potomac Piers Are Criticized, Supported As Immoral, Vital to Local Economy," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, February 22, 1958, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19580222&id=RjRWAAAAIBAJ&sjid=1OcDAAAAIBAJ&pg=3188,3412282&hl=en; Susan Hickey Shaffer, "Slot Machines in Charles County, Maryland: 1910-1968," University of Maryland masters thesis, 1983, p.60, http://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/16861 (last checked November 1, 2015)

8. "Las Vegas on the Potomac," Saturday Evening Post, September 7, 1957, p.88; "Beach's New Self Is Lady Fortune to Pier Owner Delbert Wayne Conner," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, July 23, 1954, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19540723&id=h6leAAAAIBAJ&sjid=UIoDAAAAIBAJ&pg=5512,1646036&hl=en (last checked November 2, 2015)

9. "Vegas-on-Potomac," Washington Post, June 11, 2003 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2003/06/11/AR2005033107171.html; "Remembering ~ Excursion Vessels of New York Harbor," World Ship Society, http://worldshipny.com/citykeansb.shtml; Susan Hickey Shaffer, "Slot Machines in Charles County, Maryland: 1910-1968," University of Maryland masters thesis, 1983, pp.63-64, http://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/16861 (last checked October 31, 2015)

10. "About Us," Coles Point Tavern, http://www.colespointtavern.com/index_files/Aboutus.htm; "Maryland Police Charge Virginia Tavern Owner," The Free Lance-Star, August 17, 1979, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19790817&id=h-BLAAAAIBAJ&sjid=Z4sDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2221,2138885 (last checked October 31, 2015)

11. "Md. Gambling Again Proves A Boon To Va. Town," Washington Post, April 30, 1993, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1993/04/30/md-gambling-again-proves-a-boon-to-va-town/f22b06ae-d0ee-4a6b-8917-fc6c8f35e36c/; "The Beach Bounces Back," Chesapeake Bay Magazine, September 2004, http://www.chesapeakeboating.net/Publications/Chesapeake-Bay-Magazine/1999/From-the-Chesapeake-Bay-Magazine-Archives/Destination-Colonial-Beach-VA.aspx; "Take a gamble across the state line," Southside Sentinel, August 26, 2008, http://www.ssentinel.com/index.php/rivah/article/take_a_gamble_across_the_state_line (last checked November 1, 2015)

12. "Va. House Wants Maryland To Keep Slots Off the Potomac," Washington Post, February 20, 2003, online at Maryland State Archives, http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5700/sc5796/000005/000000/000003/unrestricted/post20feb2003.html (last checked November 1, 2015)

13. "Maryland raising stakes in casino wars with Delaware and West Virginia," Washington Post, March 31, 2013, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/maryland-raising-stakes-in-casino-wars-with-delaware-and-west-virginia/2013/03/31/d90dde90-96f7-11e2-a976-7eb906f9ed9b_story.html; "Maryland Politics," Washington Post, November 7, 2012, (last checked February 10, 2014)

14. Projected Gaming Revenues and Impacts of Proposed New Casinos in Prince George's County, Maryland (DRAFT), Cummings Associates, November 26, 2013, Maryland Gaming website, http://cdn.mdlottery.com.s3.amazonaws.com/Gaming/Consultant%20Reports/Task%20I%20II%20Cummings%20Associates.pdf; "Maryland Casinos Draw Mostly Local Crowds," Capital News Service, December 21, 2012, http://cnsmaryland.org/2012/12/21/maryland-casinos-draw-mostly-local-crowds/ (last checked February 12, 2014)

15. Robert C. Johnson, "The Lotteries of the Virginia Company, 1612-1621," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 74 Number 3 (July 1966), http://www.jstor.org/stable/4247219;

"Mountain Road Lottery: Setting the Record Straight by Ron Shelley," http://mountainroadlottery.blogspot.com/ (last checked July 3, 2015

16. "Casino Gaming In Hampton Roads Potential Revenues, Economic Impacts & Social Impacts," Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization and the Hampton Roads Planning District Commission, September 2013, pp.3-4, http://www.hrtpo.org/uploads/docs/LegADhoc091613/0916013LEG-A8-Casino%20Gambling-HRTPO-HRPDC%20White%20Paper.pdf (last checked February 24, 2015)

17. "Bill allowing Portsmouth casinos clears committee," The Virginian-Pilot, February 4, 2014 , http://hamptonroads.com/2014/02/portsmouth-casinos-bill-clears-committee-hurdle; "Portsmouth City Council supports casino bill, opposes Victory development," The Virginian-Pilot, November 11, 2015, http://www.pilotonline.com/news/government/local/portsmouth-city-council-supports-casino-bill-opposes-victory-development/article_15a3ac9c-10ad-53b0-9054-1d7daf350ebf.html (last checked November 11, 2015)

18. "The Economics Of Casino Gambling In Hampton Roads," in The State Of The Region - Hampton Roads 2015, Old Dominion University, 2015, p.131, http://www.stateoftheregionreport.com/home.html (last checked November 3, 2015)

19. "Virginia resists the siren call of casinos as gambling halls proliferate across the country," Washington Post, November 29, 2013, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-resists-the-siren-call-of-casinos-as-gambling-halls-proliferate-across-the-country/2013/11/29/d33c51c8-56b3-11e3-8304-caf30787c0a9_story.html; "Portsmouth gambling proposal still faces long odds," The Virginian-Pilot, December 17, 2013, http://hamptonroads.com/node/700441 (last checked December 19, 2013)

20. "Sen. Lucas' Virginia casino bills fail on 8-7 party line vote in committee," Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 23, 2017, http://www.richmond.com/news/virginia/article_ae92bb57-e1d0-531d-ba52-bcd0aa9e2786.html (last checked January 24, 2017)

21. "Comments on the Proposed Finding for Federal Acknowledgment of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe," Stand Up for California and MGM

National Harbor (Perkins Coie LLP), July 22, 2014, in "Third-Party Comments on the January 16, 2104, Proposed Finding for Acknowledgment of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323)," Bureau of Indian Affairs, September 10, 2014, http://www.bia.gov/cs/groups/xofa/documents/text/323_pf_third_party_comments.pdf (last checked November 3, 2015)

22. "Is a casino in Virginia's future now that the Pamunkey have U.S. recognition?," Washington Post, July 11, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/is-a-casino-in-virginias-future-now-that-the-pamunkey-have-us-recognition/2015/07/11/ab924cf4-24e8-11e5-aae2-6c4f59b050aa_story.html; "Caught in the Middle: How State Politics, State Law, and State Courts Constrain Tribal Influence over Indian Gaming," Marquette Law Review, Volume 90 Issue 4 (Summer 2007), p.981, http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1075&context=mulr; "Legal Distinction Between Class II and III Gaming Causes Innovation, Anguish," Indian Country Today, October 4, 2011, http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2011/10/04/legal-distinction-between-class-ii-and-iii-gaming-causes-innovation-anguish-55045; "Pamunkey Indian Tribe planning $700 million resort, gaming facility," Daily Press, March 16, 2018, http://www.dailypress.com/news/politics/dp-nws-pamunkey-20180315-story.html (last checked March 31, 2018)

23. "Pamunkey Indian Tribe working on plans to build massive world-class casino in Virginia," The Virginian-Pilot, April 27, 2018, https://pilotonline.com/news/government/local/article_6d1ca644-497b-11e8-a905-7bdec4979f8c.html (last checked May 8, 2018)

24. "Sen. Lucas pushes for casinos again, despite Portsmouth mayor's objections," The Virginian-Pilot, October 31, 2015, http://hamptonroads.com/2015/10/sen-lucas-pushes-casinos-again-despite-portsmouth-mayors-objections; "Pamunkey Indians wanted to open Virginia's first casino, letter shows," Washington Post, October 23, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/pamunkey-indians-wanted-to-open-virginias-first-casino-letter-shows/2015/10/23/c60bda3c-71e1-11e5-8d93-0af317ed58c9_story.html; "Pamunkey Indian Tribe planning $700 million resort, gaming facility," Daily Press, March 16, 2018, http://www.dailypress.com/news/politics/dp-nws-pamunkey-20180315-story.html (last checked March 31, 2018)

25. "The Economics Of Casino Gambling In Hampton Roads," State of the Region 2015, Center For Economic Analysis And Policy, Old Dominion University, October 2015, pp.126-131, https://www.odu.edu/content/dam/odu/offices/economic-forecasting-project/docs/2015/2015-sor-casino-gambling.pdf (last checked June 1, 2018)

26. "Frequently Asked Questions - Tourism," MGM Resorts International, http://www.mgmnationalharbor.com/faq/tourism.aspx (last checked October 31, 2015)

27. "Atlantic City casino closings, one year later," Atlantic City Press, September 2, 2015, http://www.pressofatlanticcity.com/business/atlantic-city-casino-closings-one-year-later/article_ad30c2dc-4ddf-11e5-9e8e-c3e90ff53823.html (last checked November 3, 2015)

28. "Criticism Shadows D.C. Slots Catalyst," Washington Post, June 21, 2004, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A56463-2004Jun20.html; "Group Pushing Legalized Gambling In D.C. Wants To Open Casino In Anacostia," WAMU radio, March 30, 2016, https://wamu.org/news/16/03/29/empresario_wants_to_legalize_gambling_in_dc_first_site_set_for_anacostia (last checked April 1, 2016)

Colonial Beach was far from an urban area, but customers from as far away as Richmond could drive US 301 to access the "Las Vegas of the Potomac"

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Boundaries and Charters of Virginia

Virginia Places