the North Fork of the Shenandoah River has cut through Little North Mountain to carve Brocks Gap, a water gap (with a flowing river) west of Timberville

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Rocky Mount Fire, Virginia

the North Fork of the Shenandoah River has cut through Little North Mountain to carve Brocks Gap, a water gap (with a flowing river) west of Timberville

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Rocky Mount Fire, Virginia

The rivers we see today are flowing in different channels from the "original" rivers that developed 300-250 million years ago, after continental plates collided and pushed up the ancestral Appalachian mountains,

The rivers we see today are flowing in different channels from the "original" rivers that developed 300-250 million years ago, after continental plates collided and pushed up the ancestral Appalachian mountains,

As rain flowed down the mountains, rivers encountered rocks that were very hard to erode. Some streams slowed their downcutting, while others etched faster and lower. We can see some of the results of this unequal erosion in the "wind gaps" and "water gaps" of the Blue Ridge.

Turn on your imagination, and visualize today's Northern Virginia being unoccupied by humans and covered with several thousand feet of rock. Make it simple, and image the surface being as flat as it is today. On top of that rock, imagine a series of rivers running east to the Atlantic Ocean.

Don't assume the rivers start at the current Blue Ridge mountains, like today's Occoquan and Rappahannock and York River (the principal tributaries of the York in the Piedmont are known as the Mattaponi, the North Anna, and the South Anna). Instead, visualize these as equal-sized rivers, all starting in West Virginia, then running eastward in parallel straight lines before emptying into the Atlantic.

Now, let your imagination help you dig the rivers deeper and deeper into the rock of eastern Virginia. Etch out valleys, wash the sediments downstream, and dig a little deeper. Close your eyes for a moment if it helps to imagine this. If the rock of eastern Virginia is uniformly hard or soft, all the rivers you are visualizing will erode at the same pace and maintain their basic shapes... just a little lower in elevation each century, as they cut deeper and deeper in the natural erosional cycle.

But what if the rivers run into a barrier of hard rock, a volcanic layer that is very slow to erode and perpendicular to their channels? They'll all etch away at it slowly, and eventually they will all erode through that layer of rock completely. But what if the northernmost river encounters softer, fractured rock while the others are slowed down in their erosion cycle?

Then that northern river - the Potomac - will get a competitive advantage. It will dig a deeper valley, relative to the other rivers. The Potomac streambed will get lower and lower in elevation while other rivers to the south are still eroding slowly at a higher elevation. Small streams draining into the Potomac will get lower too, as the extra mechanical energy for their waters carves into the western Virginia bedrock faster than the other streams feeding the rivers to the south.

At some point, the Potomac tributaries will be substantially lower than the tributaries to the ancestral Occoquan just to the south. One little Potomac tributary will erode into the valley of a stream that formally flowed to the Occoquan. Water runs downhill, of course, so the Occoquan tributary will be diverted to the Potomac. Instead of flowing east to the Occoquan, the tributary will begin to flow north to the Potomac. The Occoquan itself will keep flowing - but with a little less water, while the Potomac gains both a little water and a little energy to cut into bedrock even faster.

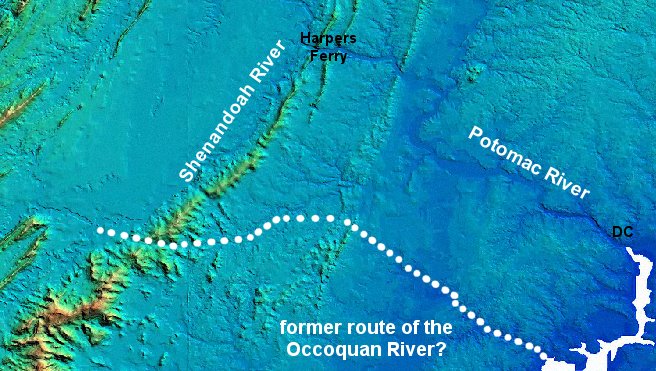

Possible route of the ancient Occoquan River (click on image for to judge for yourself)

Source: Earth Resource Mapping - USA DEM Mosaic (requires plug-in available on site)

That pirate of a tributary, intercepting different streams and redirecting them to the Potomac, grew to become the Shenandoah River. It was the first of the tributaries in western Virginia to reach the soft limestone layer that's now the base of the Shenandoah Valley. That tributary intercepted stream after stream west of the Blue Ridge, beheading first the Occoquan and then the Rappahannock and then the tributaries of the York. After each capture, the Shenandoah and the Potomac grew larger.

The Shenandoah carved out the Shenandoah Valley, dissolving the limestone and carrying the sediments north to the Potomac. Today, going "down the valley" means going north - downhill, just like the river. "Up" on the map is not "up" by topography. Going "up the valley" means going south from the Potomac River towards Staunton.

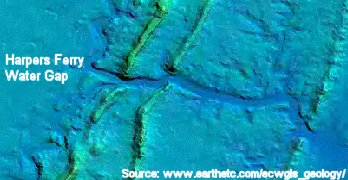

The Shenandoah joined the Potomac west of the hard Blue Ridge barrier. The Potomac kept cutting through the volcanic bedrock of the Blue Ridge, with the energy provided by the extra water pirated from other streams. You can see the "water gap" in the Blue Ridge Mountains through which it still flows, at a place known today as Harper's Ferry. Thomas Jefferson thought it was so beautiful a sight it was worth a trip across the Atlantic...but then, he lived in the days before modern electronic entertainment.

Blue Ridge gaps on 1769 map of Frederick County

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the county of Frederick, 1769

Water gaps, where the river narrows to cross through a mountain range, are logical places for scenic overlooks. Today on the Delaware River between Pennsylvania and New Jersey, the National Park Service manages the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area to preserve the natural beauty. However, that happened only after a bitter political battle over the proposed Tocks Island dam and reservoir. The Federal government was already buying houses and moving people out of the area to be flooded when the decision to build the dam at the Delaware River water gap was reversed.

Three rivers cut through the Blue Ridge and created "water gaps" in Virginia. The Potomac, James, and Roanoke rivers had enough energy to erode the rocks they encountered. The water gaps provided easy routes for roads. Modern highways utilizing the water gaps include:

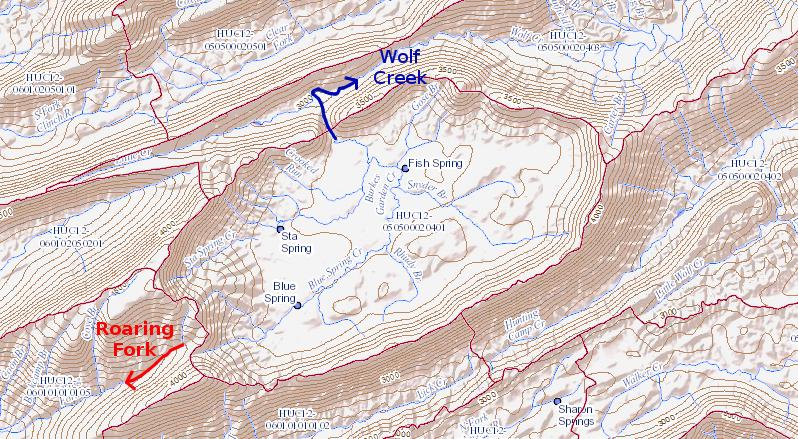

There is no water gap through the Blue Ridge south of the gap carved by the Roanoke River. The resistant bedrock of the Blue Ridge blocked the upper reaches of the New River and diverted the waters to the northwest. However, with additional flow from tributaries such as Wolf Creek, the New River had the energy to carve its channel deep into the sedimentary layers in West Virginia.

The Potomac River cut through the Blue Ridge perhaps five million years ago, and its southern tributaries etched deeper than tributaries of streams that were slowed by the resistant bedrock. Gradually, the Potomac River tributaries cut into the path of other streams and diverted them to the north. With less water, the rivers flowing eastward across the mountains had less energy.

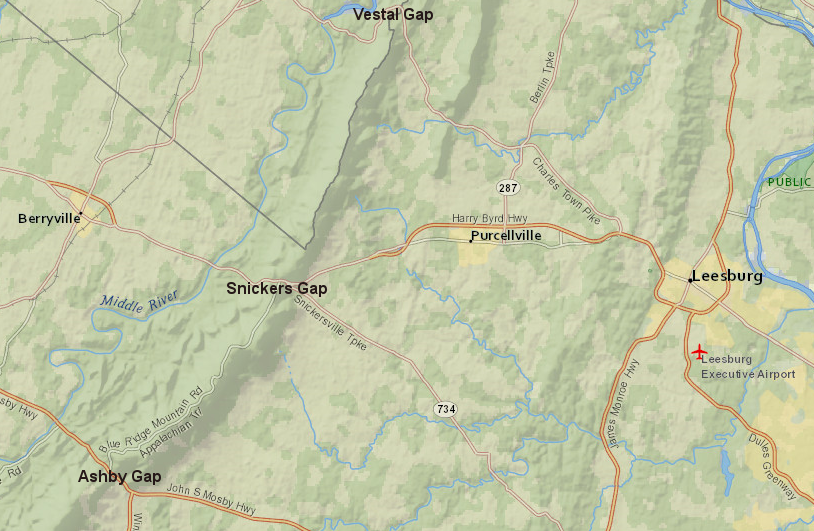

Ultimately, all the waters west of the Blue Ridge flowed down the Shenandoah River to the Potomac River's water gap. Rivers that once crossed the Blue Ridge were truncated, and ended up with headwaters on just the eastern side of the mountains. We can still see the ancient notches carved in that hard volcanic Blue Ridge bedrock before stream piracy robbed the southern streams of their western headwaters.

Each notch, or "wind gap" because only the wind crosses it now, is a low spot in the Blue Ridge. There are 100 wind and water gaps along the 470 miles of the Blue Ridge Parkway stretching from Great Smoky Mountains National Park to Shenandoah National Park.

Not surprisingly, each major wind gap has a highway crossing the mountains. From the Potomac River south to Afton Mountain near Charlottesville, modern roads crossing the ancient gaps include:1

trails and then roads crossed through the Blue Ridge at topographic low spots

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Stream piracy is not unique to the Shenandoah Valley. The Pinnacles of Dan in Patrick County show the erosive power of the rivers draining southeast to the Atlantic Ocean is greater than those streams draining west to the Gulf of Mexico, much further away. Cumberland Gap in far southwestern Virginia, through which Daniel Boone led settlers into Kentucky along the Wilderness Road, is a wind gap now.

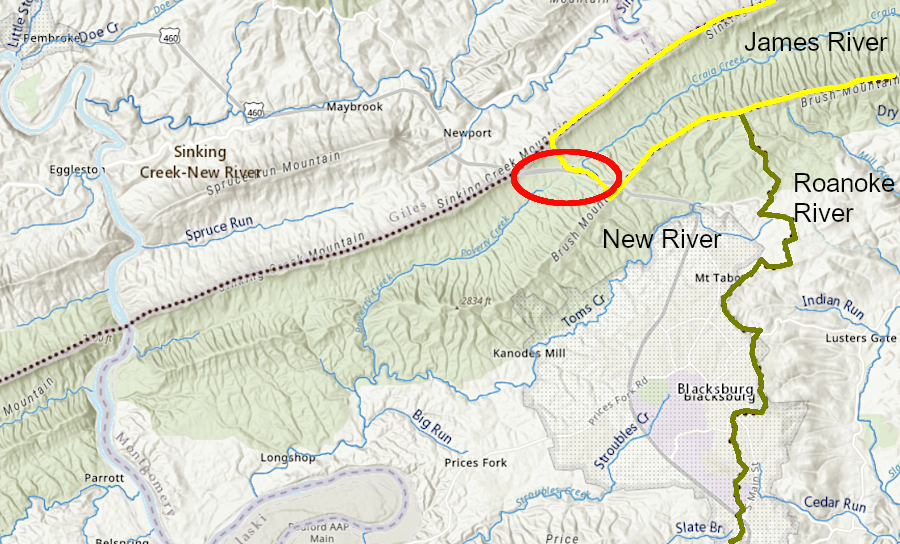

Stream piracy is still occurring, with the potential for a dramatic revision of Virginia's watersheds relatively soon near Blacksburg. "Soon" is measured in geological time... none of us will live to see this change occur naturally.

Virginia has a portion of what has often been claimed to be the second-oldest river in the world, named ironically the New River. It will be beheaded in Montgomery County by Craig Creek. When Craig Creek finishes cutting across Highway 460, drains the little Pandapas Pond managed now by the Forest Service, and intercepts the New River downstream from McCoy Falls. At that point, the New River will be redirected to the Atlantic Ocean.

To spot the future site of stream piracy, follow Craig Creek upstream from Bessemer, Virginia. As Craig Creek erodes southwest across US 460, it will erode the Poverty Creek channel deeper and eventually intercept the New River. At that time, the water in the New River will flow towards the James River, reaching it just downstream from Iron Gate. By the time the James River beheads the New River, an eon or two from now, the need to dilute the outflow from the paper mill in Covington into the Jackson River will be long, long forgotten.

Craig Creek may etch upstream past the watershed divide at US 460 (red circle) and "pirate" the New River, diverting that water into the Chesapeake Bay via the James River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online; Chesapeake Bay Program, CBP Data Project LULC and Hydrography Viewer

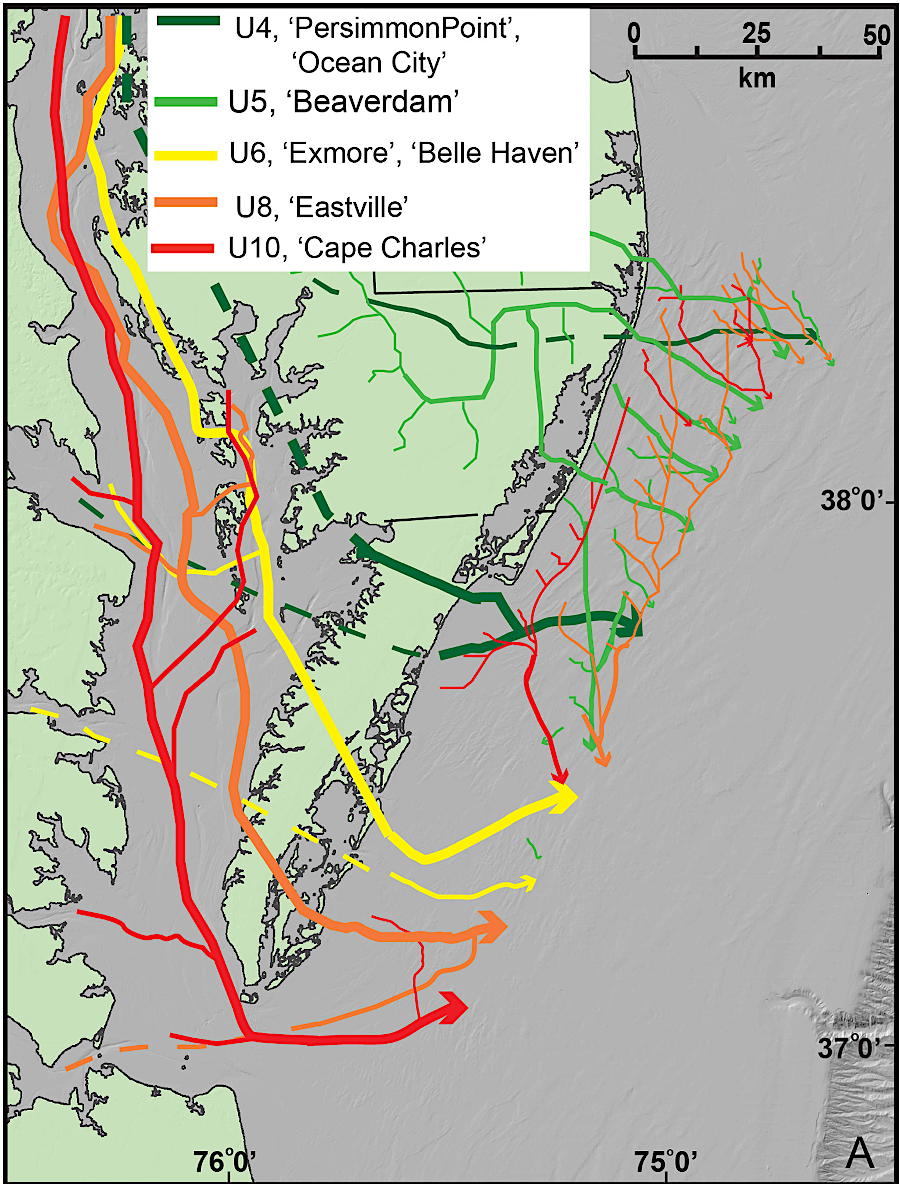

One of the most significant stream captures in Virginia is on the eastern side of the state. The Delmarva Peninsula was created as sea levels rose and fell during the late Neogene and Quaternary periods.

The Susquehanna River deposited sediments at its mouth when sea levels were high. During the ice ages, there was less water flowing in the river and sea level dropped. The diminished Susquehanna River lacked the erosive force to cut through the deposits.

Those sediments became a barrier, so the Susquehanna River prograded south and carved a new channel around them. In the process, the Susquehanna captured the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James rivers. Those four rivers had been flowing directly eastward, across what is now the Delmarva Peninsula and the continental shelf, into the Atlantic Ocean. Today the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James rivers are tributaries flowing into the flooded channel of the Susquehanna River (the Chesapeake Bay).2

location of Susquehanna River paleochannels across the Eastern Shore

Source: Marine Geology, Seismic stratigraphic framework of the continental shelf offshore Delmarva, U.S.A.: Implications for Mid-Atlantic Bight Evolution since the Pliocene (Figure 9)

Burkes Garden once drained through Roaring Fork/Holston River into the Tennessee River, before stream piracy by Wolf Creek redirected flow to the New River

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Map