Mount Pony houses the Packard Campus of the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center of the Library of Congress

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Mount Pony houses the Packard Campus of the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center of the Library of Congress

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1969, the Federal government excavated within Mount Pony a 400-foot long, 140,000 quare foot bunker with steel-reinforced concrete a foot thick. That created a radiation hardened facility for the Federal Reserve. It installed the Culpeper Switch, used in the Federal Reserve Communications System (Fedwire) system for electronic bank transfers. Fedwire transferred funds and government securities among 5,700 commercial banks that were part of the Federal Reserve system.

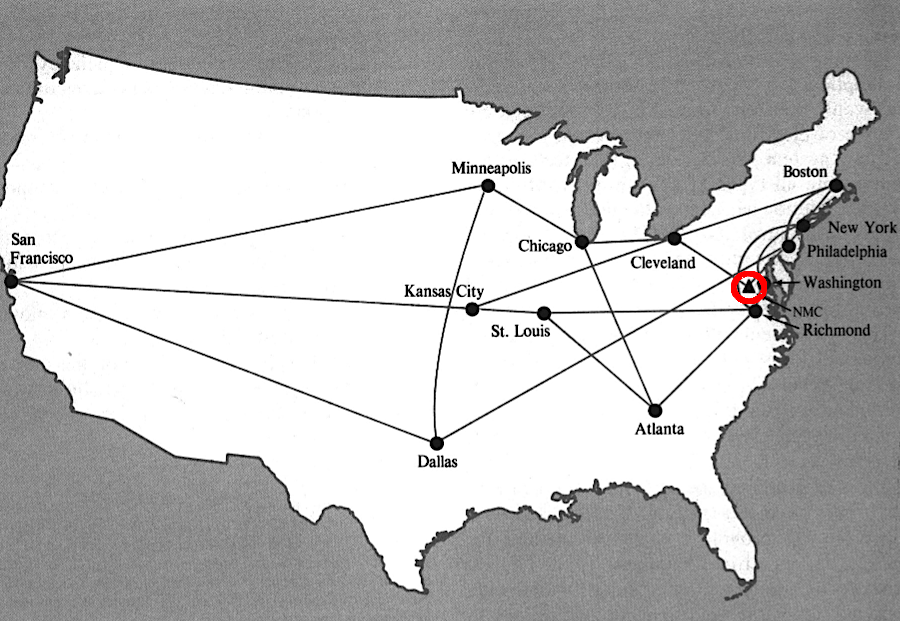

The first interbank transfers were handled by the Federal Reserve starting in 1915, two years after the Federal Reserve System was founded. A private telegraph wire system was created in 1918. It relied upon Morse code messages until teletype machines were installed in 1937. In 1953, a nationwide automatic message system was created. Main relay stations were in Washington, DC for traffic in the eastern states and in Chicago for the western states.

The communications network was centralized and upgraded in 1953. To minimize the risk of disruption by a Soviet Union attack, teletype switching equipment was installed on two floors of the Richmond Federal Reserve.

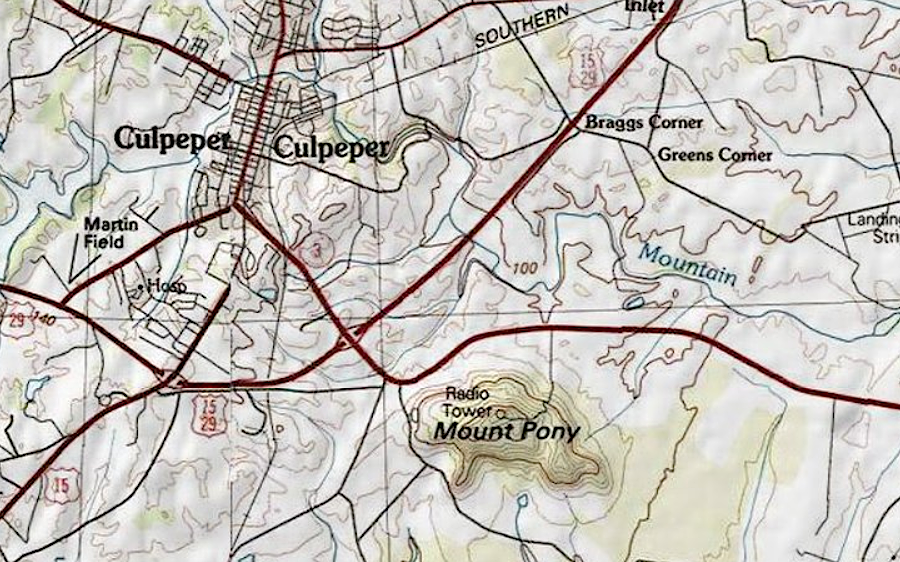

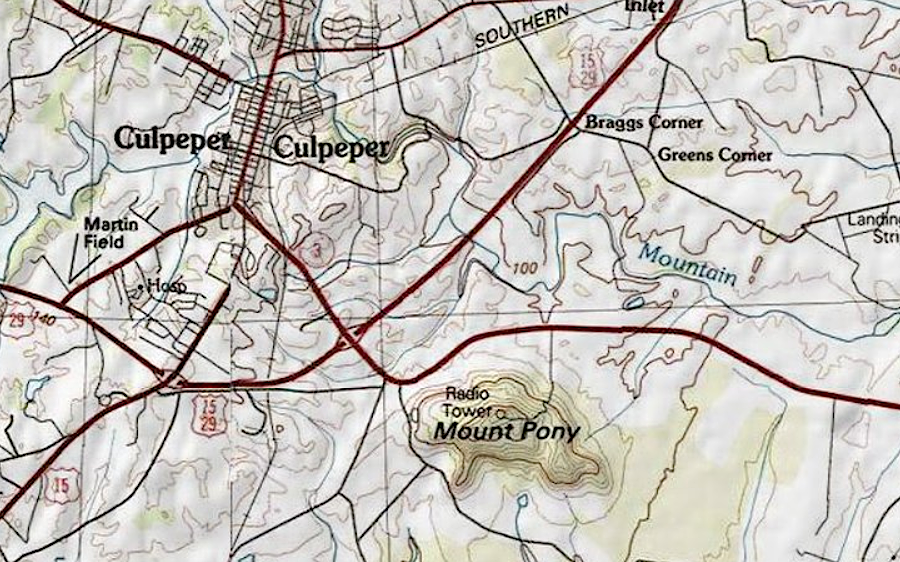

The network was computerized in 1969 and moved to Mount Pony, outside of expected nuclear blast zones. The Richmond bank had been planning to use the site for records storage. The Inskeep family, which had owned Mount Pony since 1774, sold the land to the Federal Government. Fedwire operations started there in 1970.

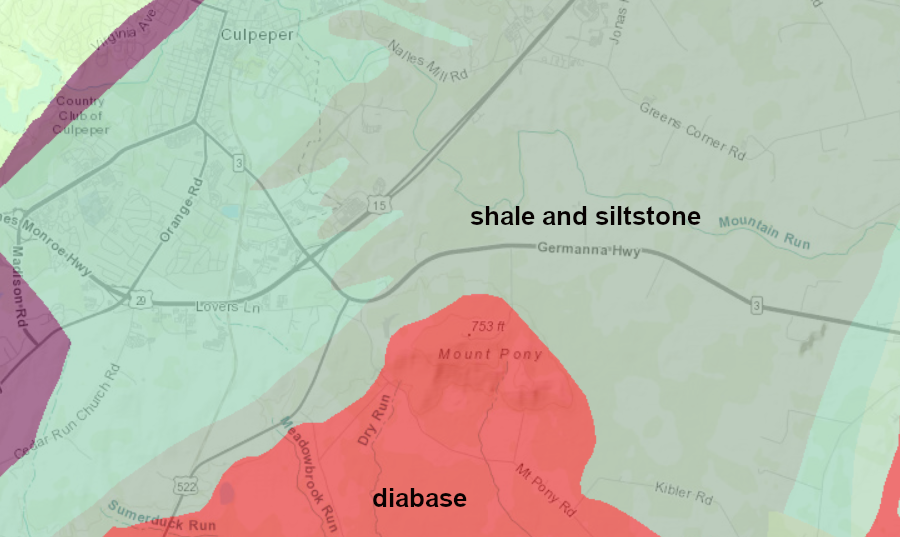

Mount Pony is a hill because the hard basalt has eroded more slowly than the surrounding Triassic Basin sedimentary formations

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Geology Mineral Resources

The Federal Reserve carved the underground bunker out of the hard basalt, installed blast doors, and covered the Communications and Records Center with several feet of dirt. As described by the Federal Reserve in 1975:1

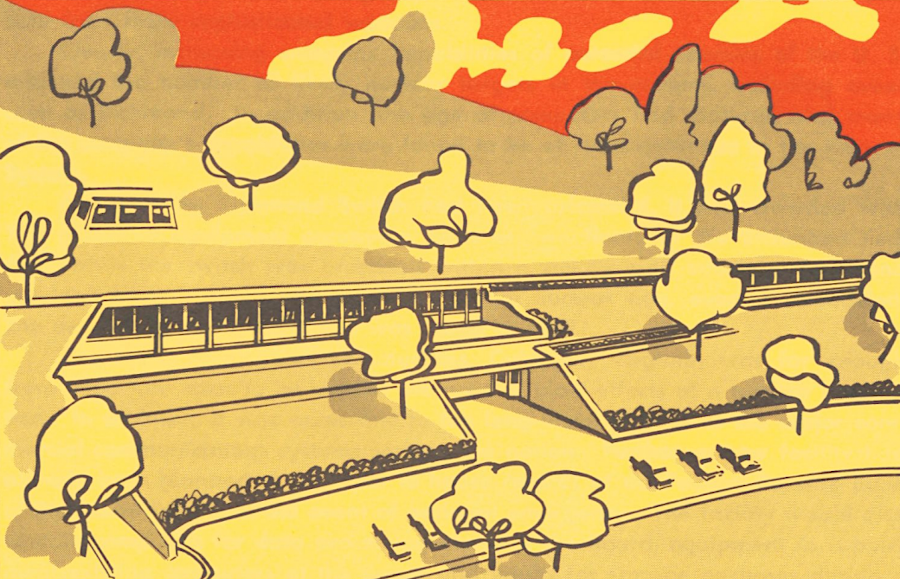

the Federal Reserve carved a bunker into Mount Pony for a communications and records storage facility

Source: Federal Reserve System, The Culpeper Switch

At the dedication of the Mount Pony facility in 1969, the vice-chair of the Federal Reserve Board explained why Culpeper had been selected:2

In 1982, Fedwire was redesigned from a centralized star to a distributed packet-switched network; the Culpeper Switch no longer served as the essential node for all messages. Mount Pony's role in transmitting and receiving Fedwire messages ended in the 1990's, making it surplus to the Federal Reserve.3

Fedwire relied upon the Culpeper Switch at Mount Pony between 1970-1982

Source: Federal Reserve Bulletin, Federal Reserve and the Payments System - Upgrading Electronic Capabilities for the 1980s (February 1981)

The records component of Communications and Records Center included stockpiling $4 billion worth of $2 bills. Mount Pony was planned to serve as perhaps the last remaining source of Federal funds after a nuclear war, and would distribute the $2 bills in order to reestablish the currency supply east of the Mississippi River.

To deal with the distribution, the underground bunker had supplies and space for 400 people. There were only 200 beds; plans were for half the people to always be working, so "hot bunking" would be used to minimize space requirements.

The idea that a few remaining government officials would spread $2 bills and restart the economy in the apocalyptic aftermath of a nuclear was a questionable scenario. Sen. William Proxmire made clear in 1976 that he thought the currency redistribution plan was unrealistic:4

After the Culpeper Switch was shut down and the threat of a nuclear attack diminished by the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Federal Reserve no longer needed Mount Pony. Attempts to sell the facility to the private sector drew no bidders.

Source: Museum of Culpeper History, The National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, Packard Campus, in Culpeper, Virginia

The site did draw the attention of the Library of Congress. It was seeeking a new location for storing and preserving film. During World War II, the National Archives briefly used concrete bunkers at Fort Hunt in Fairfax County for the Nitrate Film Depository. Flammable nitrate film stored by the National Archives and other Federal agencies was a safety hazard, so moving that film stock to vaults in four refurbished batteries at Fort Hunt was a temporary wartime security measure.

However, the bunkers were not watertight and did not provide a climate controlled environment. In 1946, the National Archives completed a new depository in Suitland, Maryland. All remnants of the Nitrate Film Depository were moved out of Fort Hunt that year.5

Mount Pony was transferred to the Library of Congress on July 26, 2007. David W. Packard and his Los Altos-based charity, the Packard Humanities Institute (PHI), donated $155 million to establish the Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation. The gift included $5.5 million to purchase Mount Pony and donate it to the Library of Congress.

The private funding, along with $87 million from the US Congress, permits the storage, conservation, digitization, and display of the video and audio artifacts that were transferred to Culpeper from the Jefferson and Madison buildings on Capitol Hill, plus buildings in Landover and Suitland (Maryland) and at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Nitrate-based films created before 1951 is now stored safely at the Packard Center. Most of the center is almost all underneath a green roof the size of three football fields:6

most of the Packard Center is underneath a green roof, except for the main entryway and the west front of the Conservation Building

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Packard Center