How Counties Got Started in Virginia

Charles City County originally included land on both sides of the James River, and the name of City Point near the mouth of the Appomattox River is a residue of those boundaries

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of Virginia, Maryland, and the improved parts of Pennsylvania & New Jersey (1685)

Counties were not planned in advance to be part of the English settlement in Virginia in 1607. The new colony was a private company's investment, governed by the stockholders of the company until it went bankrupt and the charter was revoked by King James I.

Government in Virginia, including the formation of counties and cities, evolved in reaction to unplanned events. In 1607, there was no expectation that the venture capitalist investment in a foreign land would result in "government of the people, for the people, by the people." A risky business, not the concept of democracy, was imported into Virginia on the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery.

The Virginia Company of London was managed by a council in London, originally appointed by King James I. The company sent its colonists to the New World without even announcing who would be the local leaders in Virginia. When the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery finally reached the James River, Captain Newport opened the sealed envelope with the London Company's instructions - and had to release Captain John Smith from confinement, so that prisoner could take his place on the resident council.

Until 1624, the colony of Virginia was a business managed by the equivalent of a plant manager - the "president" of the council, replaced by the "governor" starting in 1610. He had to deal with a local oversight board - the appointed council, then after 1619 a General Assembly as well.

The company's "Board of Directors" was the London Company, which was led by its Treasurer. The directors, key investors in the company, remained in England.

Leadership in the colony was never easy. Ships required weeks to cross the Atlantic Ocean, so direction from London was often inappropriate. Company and then colonial officials in Virginia had to use their own judgment, and often delayed or ignored directions from London to take specific actions.

The Virginia Company's appointed councilors in Jamestown experienced serious interpersonal conflict, weaking the authority of local company management. In the early days of Jamestown, one local member of the council, Captain George Kendall, was executed as a Spanish spy in 1608.

John Smith was almost executed by his Council rivals. The explosion of his gunpowder pouch in 1609 while he slept, which damaged his thigh and caused him to return to England in October, may have been an assassination attempt rather than an accident.

The London Company changed its business strategy after the "starving time" in 1609-10 and the failure of the colony to thrive. Potential investors were offered a great deal of flexibility in creating new settlements to attract settlers.

The potential to own land stimulated shiploads of settlers, ultimately leading to the creation largely self-sufficient "hundreds." The name may have reflected the anticipated number of new settlers required to establish a permanent community. These new hundreds were required to be at least several miles from any existing community. One, Bermuda Hundred, became a famous place name on the James River during the Civil War.

Within the Virginia Company in London, there were internal disputes almost as intense as in Jamestown. Some investors wanted to maintain strict discipline over all colonists, as reflected in the "Laws Divine, Morall and Martiall." The faction led by Thomas Smythe finally lost control to the group led by Edwin Sandys, and in 1618 the company adopted the Great Charter.

A new governor, Sir George Yeardley, was sent to Virginia with the intention of making the place attractive to new settlers. The new approach included granting greater freedom to settlers, and sending more women across the Atlantic so English families could be established in Virginia. Sandys and other leaders of the Virginia Company assumed that people living in England would be more attracted to migrating voluntarily to Virginia if martial law was ended.

The 1618 instructions to George Yeardley are known today as the "Great Charter." It was guidance to officials based in Virginia from the directors of the company in London; the "Great Charter" was not a fourth charter from the king.

Yeardley's 1618 instructions provided detailed direction regarding land ownership. Revenue from company-owned parcels was to be kept separate from revenue generated from private lands, rather than commingled and both used by company officials while they lived in the colony. Virginia Company officials were tasked with delivering back to London that portion of the company's revenue that was due to the investors in England:1

- ...our intent being according to the rules of Justice and good government to alot unto every one his due...

The instructions specified acreage to be managed for the benefit of the governor, the company, colonial officials, ministers, and to establish a university. People who had "adventured" to Virginia or paid for others were awarded 100 or 50 acres of land. To manage the distribution of people, the colony was to be divided into four "incorporations" (cities or boroughs) called James Town, Charles City, Henrico, and the Borough of Kiccotan.

Each borough was granted 1,500 acres of land. The expectation was that company workers would farm that land, and a share of the profits would offset the need for taxes to support government operations. For the same reason, a 3,000-acre tract was set aside as the Governor's Land to provide his salary, and 100-acre tracts in each of the four boroughs were allocated as "glebe land" to support ministers.

The instructions also authorized "particular plantations" that would be outside the direct control of the London Company. Those particular plantations, with self-government authority, had to be located at least five miles away from the existing settlements where the company retained authority over the colonists.

Particular plantations with limited obligations to the Virginia Company officials in Jamestown were to be relocated away from the four cities or boroughs. A future fifth incorporation was considered, though never formally created. The instructions required that the particular plantations be located near each other so:2

- ...they may be incorporated by us into one body corporate and live under Equal and like Law and orders with the rest of the Colony

In 1619, the 11 small settlements elected representatives to the first General Assembly. Each of the existing population clusters was allowed two representatives. The boundaries of the four "incorporations" were irrelevant to the election process for the colonial assembly, and no elections were held for any local officials in 1619.

That first General Assembly in 1619 rejected representatives that were elected from Martin's Brandon, a particular plantation in today's Prince George County, because it was not obliged to comply with whatever decisions were made by the General Assembly.3

the 1907 Memorial Church on Jamestown Island was built on top of the foundations of the 1617 church in which the General Assembly first met

Starting with the 1619 meeting, the General Assembly (combining the Governor, Governor's Council, and House of Burgesses) handled executive, legislative, and judicial issues for the Virginia colony. The assembly created the first local courts to handle small lawsuits in 1622.4

After the Native American uprising of 1622, it was clear that the Virginia colony would never be profitable. The colony might be an outpost of English culture and government in the New World, but the stockholders would not get a good return on their investment. In 1624, King James I took official control of Virginia by revoking the London Company's charter. The General Assembly continued to meet after King James I assumed control.

Between 1624 and the American Revolution, Virginia was ruled as a royal colony of the king. In contrast to Maryland and Pennsylvania, Virginia was never a proprietary colony where authority was granted to an individual such as William Penn or Lord Calvert.

The population increase to about 5,000 colonists in 1634 caused the General Assembly's administrative workload to become a hassle. Population growth of the colony triggered a need for official decisions that were local and not of concern to the entire General Assembly, or appropriate to delay until the next session.

In 1634 the elected legislature, with the approval of the appointed royal governor, chartered eight units of local government. Local officials, appointed by the General Assembly, were expected to handle more responsibilities beyond the minor legal disputes already being resolved by local courts started in 1622.

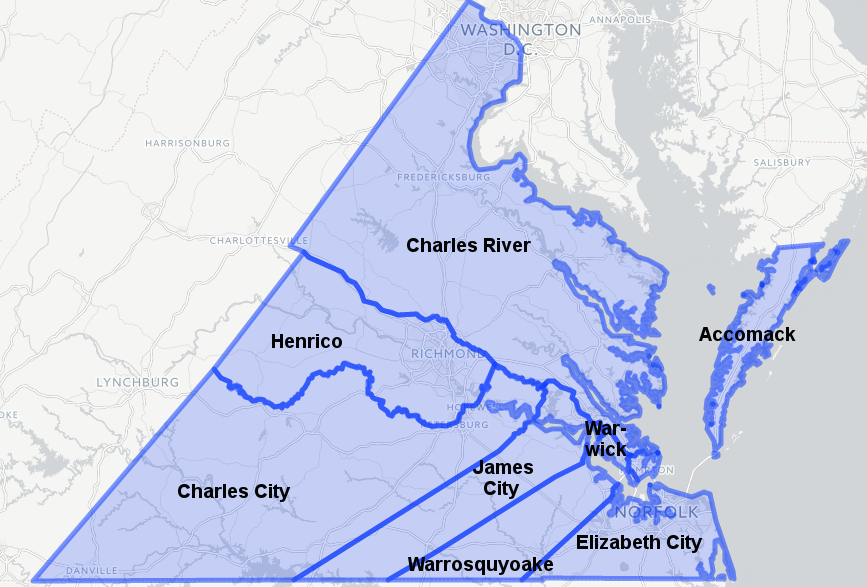

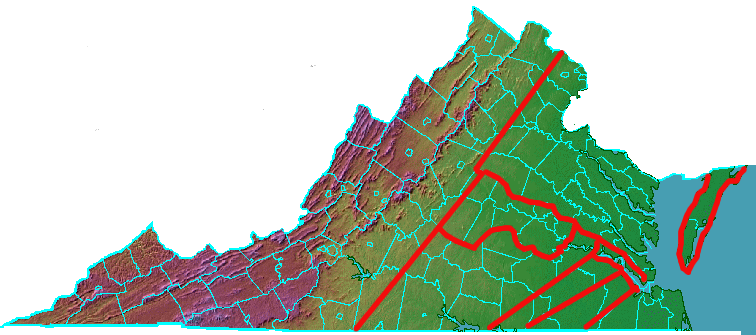

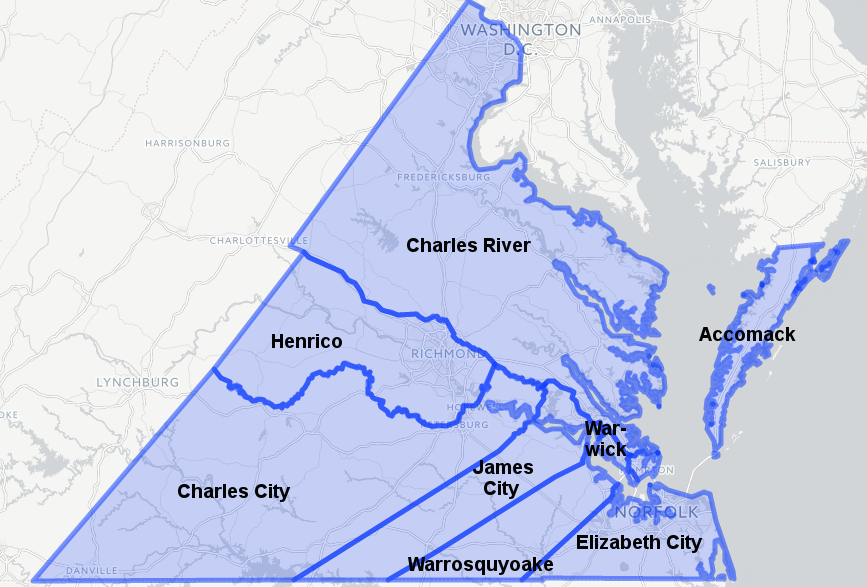

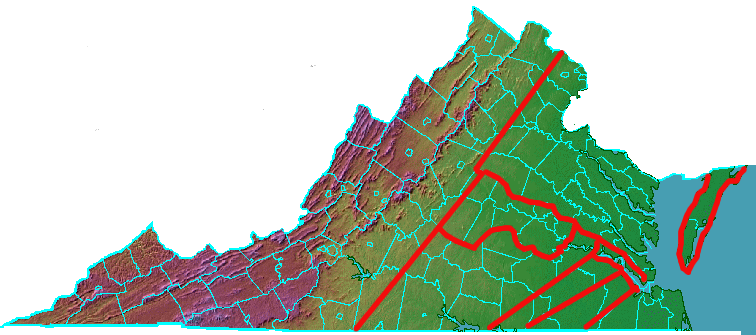

first eight shires created in 1634 included the four incorporations create in 1618 (Kecoughtan was renamed Elizabeth City) plus Accomack, Charles River, Warrosquyoake, and Warwick River

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas Of Historical County Boundaries

The term "shires" was used in the original act. Since then, those local governmental units have been described as "counties" - but the key law enforcer in most county governments is still known as the sheriff. That term was derived from shire reeve.5

The eight new jurisdictions, which were commonly called "counties" rather than "shires," included the four existing Incorporations of Henrico, Charles City, James City, and Elizabeth City. Elizabeth City replaced the "heathen" name of Kecoughtan, and is now part of the City of Hampton. Four new counties were also incorporated: Accomack, Charles River (renamed York in 1643), Warrosquyoake (renamed Isle of Wight in 1637), and Warwick River (now part of Newport News).

boundaries of the first eight counties in Virginia, extending west of the Fall Line into the Piedmont

The boundaries of future counties were drawn and then modified so most landowners in that jurisdiction could reach their county court sessions, where justices dealt with property issues and criminal accusations, in one day. County boundaries would be defined and altered until the last county of Virginia (Dickenson) was created in 1880, but the primary basis for drawing Virginia's county boundaries was to make the courts accessible.

Boundaries of local jurisdictions have changed since 1880 though annexation, consolidation, and negotiation. In 2019, Orange and Greene counties modified their boundary after discovering that some residents in the Preddy Creek subdivision in Greene County were physically located across the boundary in Orange County. The Virginia Board of Elections began to identify where voters were living outside their voting precincts after an election in 2017 ended in a tie vote, and some voters in that district had been assigned to the wrong precinct.

The state agency reported that voters in some houses traditionally thought to be located in Greene County should be assigned to Orange County precincts, which would move those voters from the Fifth Congressional District to the Seventh Congressional District. Instead, the counties revised their boundary, which had last been surveyed in 1836 before Greene County was created. The resurvey identified that the correct boundary was located further east than previously thought, so all the houses in question were in fact in Greene County. However, the survey revealed that the correct boundary would move a dozen other houses long thought to be in Orange County into Greene County.

The boards of supervisors in both counties unanimously agreed to revise the boundary so those houses would stay in Orange County. The negotiated agreement was confirmed by a Circuit Count judge, thus altering a county line that had been established in 1838 when Greene County was created out of Orange County.6

in 2019, Greene and Orange counties revised their boundary at the Preddy Creek subdivision

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Links

References

1. Alvin T. Embrey, Waters of the State, Old Dominion Press, 1931, p.14, https://archive.org/details/watersofstate00embr; "'Master Pories parlement business' - The Proceedings of the First General Assembly of Virginia, July 1619 by John Pory," Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation blog, undated, https://www.jyfmuseums.org/Home/Components/News/News/70/148 (last checked May 28, 2024)

2. "Instructions to George Yeardley" by the Virginia Company of London (November 18, 1618)," Encyclopedia Virginia, http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/_Instructions_to_George_Yeardley_by_the_Virginia_Company_of_London_November_18_1618; Alvin T. Embrey, Waters of the State, Old Dominion Press, 1931, pp.13-16, https://archive.org/details/watersofstate00embr (last checked January 12, 2022)

3. Charles E. Hatch, The First Seventeen years, Virginia, 1607-1624, Jamestown 350th Anniversary Historical, 1957, p.20, pp.75-76 http://books.google.com/books?id=GzSMXk1mAyIC (last checked December 22, 2015)

4. Robert Beverley, The History and Present State of Virginia, 1705, p.39, posted online at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/beverley/beverley.html (last checked December 22, 2015)

5. "Roots - A Historical Perspective of the Office of Sheriff," National Sheriffs Association, https://www.sheriffs.org/publications-resources/resources/office-of-sheriff (March 27, 2019)

6. "Orange, Greene agree to boundary," Greene County Record, March 22, 2019, https://www.dailyprogress.com/greenenews/news/orange-greene-agree-to-boundary/article_18607a06-4b21-11e9-9908-5fb9aa34da23.html (last checked March 22, 2019)

Virginia Counties

Virginia Places