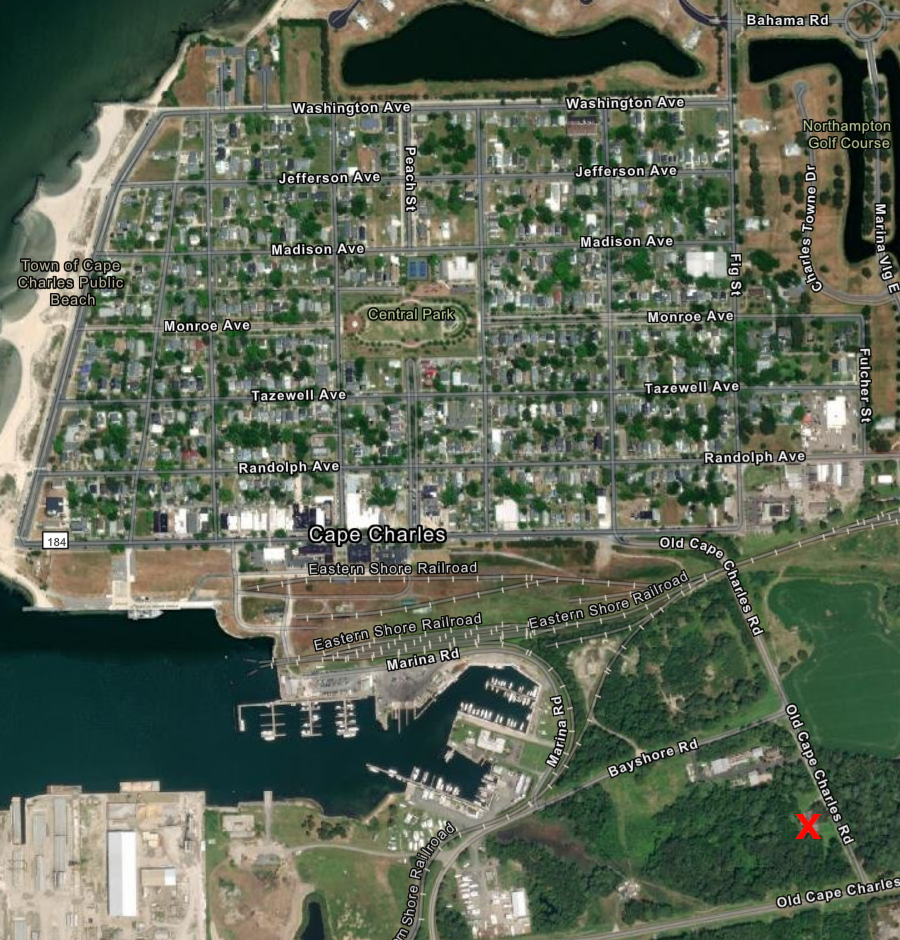

the east-west streets in Cape Charles are named after political leaders in Virginia, including Governor Littleton Waller Tazewell

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the east-west streets in Cape Charles are named after political leaders in Virginia, including Governor Littleton Waller Tazewell

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The southern tip of the Eastern Shore is Cape Charles, named by English colonists who arrived in 1607. They honored the cape after the younger son of King James I. Cape Henry, on the other side of the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay, was named after the younger son, Henry the Prince of Wales. Henry died before his father, so Charles succeeded to the throne and became ing Charles I.1

Northampton County has been predominantly farmland since European colonization. Eastville has served as the county seat since 1680.2

In 1883, the heirs of Governor Littleton Waller Tazewell sold 2,500 acres to the creators of the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad. They subdivided 136 acres of that property into 644 equal lots and created the town of Cape Charles. The town was developed as the endpoint of the new railroad, where rail cars would be barged across the Chesapeake Bay to connect to railroads in Norfolk and Portsmouth and people/wagons could travel by ferry. The track was completed through the town to the shoreline on October 25, 1884.3

The town was officially incorporated in 1886. The street grid was platted as a rectangular grid. There were originally six east-west avenues with the names of political leaders in Virginia, including Governor Tazewell. The six north-south streets were named after trees. Bay Avenue and Harbor Avenue were added in 1911 on the east end of town, as the Chesapeake Bay shoreline was extended by filling in the marshes. After adding 38 acres of land, there were 97 new building lots in town.4

The July 4, 1888 celebrations were so raucous that three separate trips were required to deliver arrested people to the jail in Eastville. After that, the town built its own jail. It was called the "Andy Dupree," in honor of the first white person to be imprisoned there.4

Cape Charles was a segregated town. The "colored section" was at the northern end along Jefferson and Washington Avenues. Black children went to school in that part of town until 1929.

The Rosenwald Fund supported construction of a new school for black children, and in 1928 Cape Charles purchased land next to the town dump as the new school site. To get to the new Cape Charles Elementary School, black children walked past the school for white children in the middle of town and crossed the "hump bridge" to get over the railroad tracks. Grades one to seven were taught in the "over the hump" school. To continue their education, black children were taken by bus to a high school out of town until the mid-1960's.5

starting in 1929, black children had to cross the bridge over the railroad tracks to reach the "over the hump" elementary school (red X)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The passenger ferry moved from Cape Charles to Kiptopeke in 1951, so travelers in cars bypassed Cape Charles. The Pennsylvania Railroad continued to bring passengers by rail to Cape Charles, but stopped operating its steamers ferrying people across the Chesapeake Bay in 1953. All the passenger trains stopped coming in 1958, and all ferries ceased operating when the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel opened in 1964.

Rail traffic declined after the Pennsylvania Railroad merged into Penn Central. When that company went bankrupt in 1970, Conrail assumed control and sought to abandon the track on the Eastern Shore. To maintain the railroad, Accomack and Northampton counties created the Accomack-Northampton Transportation District Commission and the Eastern Shore Railroad in 1976.

The Bay Coast Railroad used the track between 2005-2018 until, with no advance notice, that railroad shut down. Another Class III railroad agreed to use the track and provide freight service at the northern end of the track, but there was not enough traffic to justify continuing to use the southern 49 miles to Cape Charles. That section, first constructed by the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad, was abandoned so it could be converted into a bike/pedestrian trail.6

Cape Charles experienced economic decline after the ferry moved to Kiptopeke and travelers driving on Route 13 bypassed the town. Opening the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel in 1964 did not spur new sprawling development, with workers commuting across the bay to Virginia Beach. The lack of new development facilitated preservation of old Victorian homes in town, in a pattern similar to the preservation of historic structures at Williamsburg.

In 1991, the Cape Charles Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. At the time, there were 650 homes in the town, the same number as at the start of the Great Depression about 60 years earlier. Based on a consultant's report in 1996, the town chose to focus on tourism as its best opportunity for economic development.

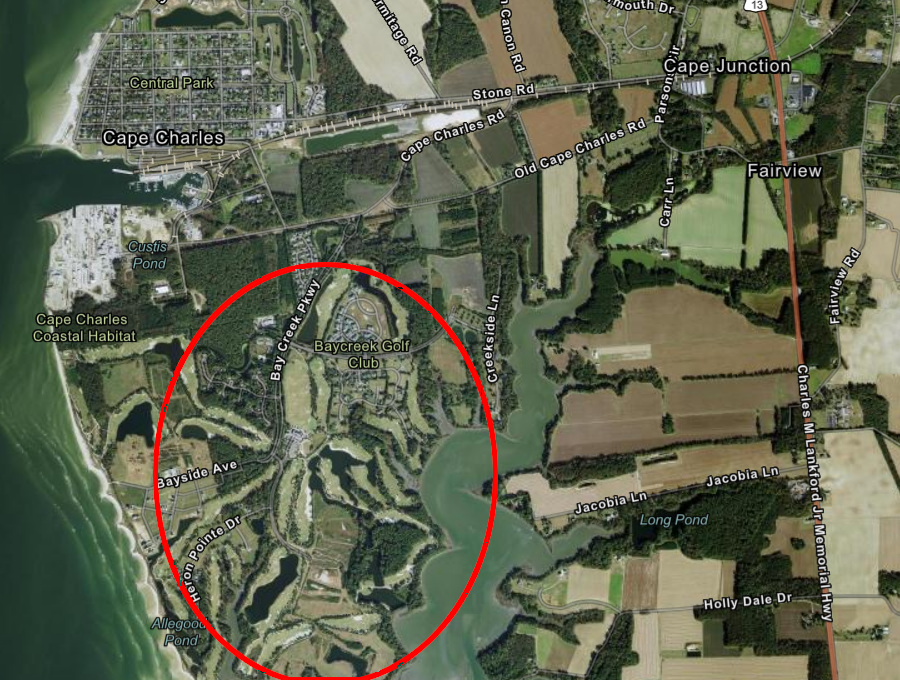

A Virginia Beach developer saw an opportunity. He purchased 1,700 acres of farmland in 1998 and gained approval to build the Bay Creek development, a gated community and resort destination with the potential of 2,500 homes and golf courses designed by Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus. Locals "born here's" welcomed the economic benefits but questioned the impact of so many new "come here's" on a small community that had experienced little change for decades. One long-time resident emphasized how the exclusiveness of Bay Creek suggested it would disrupt the traditional character of Cape Charles:7

Bay Creek was developed on 1,700 acres of farmland south of the Town of Cape Charles

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The evolution of online reservations for bed-and-breakfasts (such as Air BnB) helped trigger restoration of the historic homes in Cape Charles. Old hotels have been reopened, and the fundraising target to restore the Cape Charles Rosenwald School (the Cape Charles Elementary School) was set at $2.5 million.8

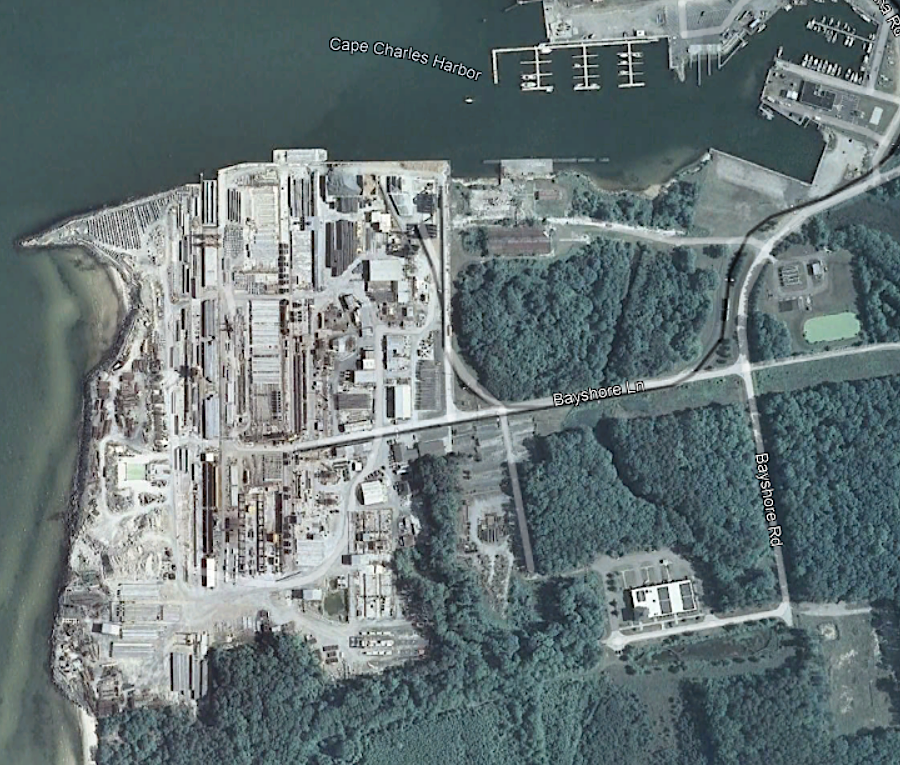

Cape Charles was built to be a railroad town. It had a bustling economy until the Great Depression, based on passengers and freight traveling through town to a barge and steamers that crossed the Chesapeake Bay. Just one major manufacturing plant has been located at Cape Charles.

Bayshore Concrete opened in 1961 to make precast concrete components for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. It produced more than 2,500 cylinder piles that were driven into the bed of the Chesapeake Bay to support the bridge. Skanska purchased two-thirds of the company in 1987, and acquired the remaining third in 2004.

By 2017, the concrete plant had upgraded its ability to produce precast concrete far beyond the requirements of the 1964 Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. The precast caps placed on top of the piles for the bridge-tunnel weighed 10-15 tons, while 450-ton caps were being made in 2017. At that time, only one other company in the United States made concrete cylinder piles like those used for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel and expansion of the Virginia International Gateway Terminal on the Elizabeth River.

The 90-acre heavy industry site at Cape Charles allowed Bayshore Concrete to manufacture and store large components before shipping, primarily via barge, to construction sites. One specialty was building segments which included both a bridge's substructure and superstructure, then floating the pre-made sections to the construction site for faster assembly.

Skanska closed the manufacturing plant in 2018, after finishing work for the Bayonne Bridge between Bayonne, New Jersey and Staten Island, New York. Bayshore failed to win the contract to make concrete components for the construction of the second tunnel underneath Thimble Shoals, as the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel expanded.

The facility was reopened by a new owner a year later and named Coastal Precast Systems. In 2021-23, it manufactured 21,000 precast concrete segments, with steel fiber and rebar, that were assembled by a tunnel boring machine to create two new tunnels at the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel. Neighbors who objected to the noise starting at 5:00am and dust formed the Citizens Concerned for Cape Charles in 2020, advocating for reductions in particulate air pollution and opposing potential rezoning of more land for heavy industry.9

in 2011, Bayshore Concrete was busy making concrete components for large construction projects

Source: GoogleEarth