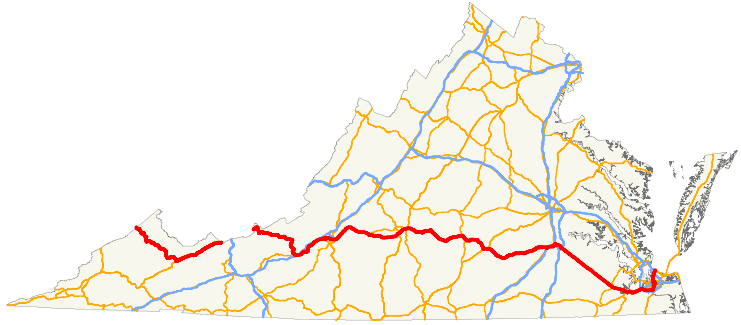

US 460 links the Coastal Plain to the Appalachian Plateau

Source: Wikipedia, U.S. Route 460 in Virginia

US 460 links the Coastal Plain to the Appalachian Plateau

Source: Wikipedia, U.S. Route 460 in Virginia

US 460 goes completely across the state, from the Atlantic Ocean in Virginia Beach to the West Virginia border in Giles County. After passing through a portion of West Virginia, the highway re-enters Virginia in Tazewell County and exits again from Buchanan County.

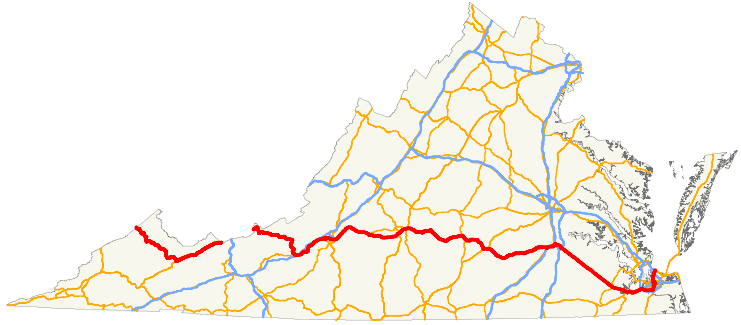

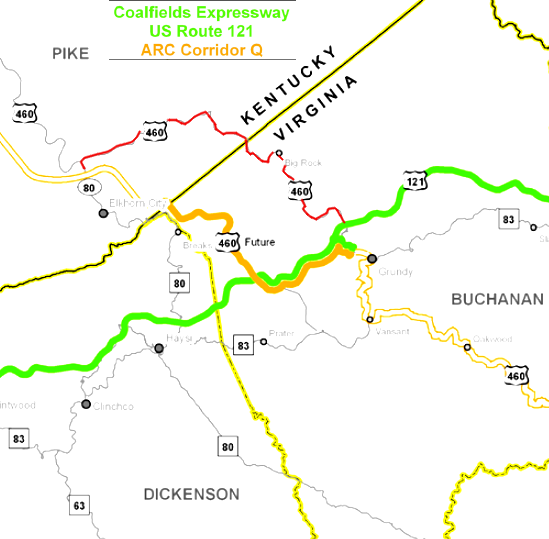

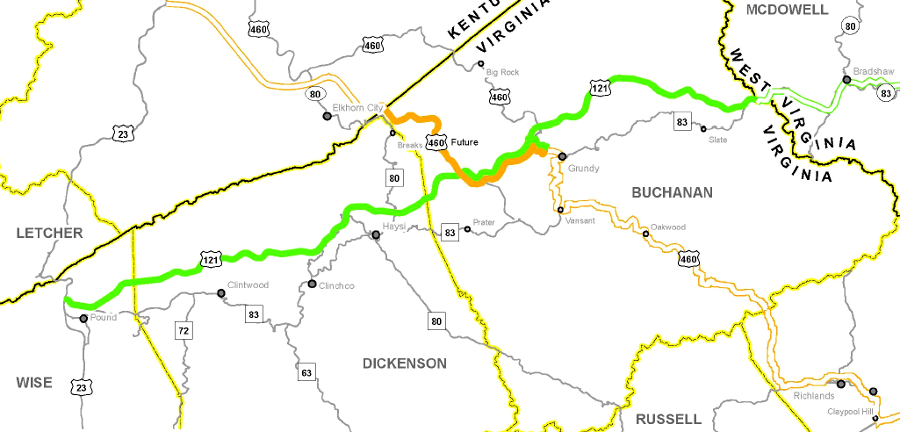

In the Appalachian Plateau, over 120 miles of US 460 between I-81 and the Kentucky border west of Grundy is also designated as Corridor Q in the Appalachian Development Highway System. That designation provides additional funding for transportation improvements through the Appalachian Regional Commission. The last part of Corridor Q to be constructed will move the highway in Virginia from the Levisa Fork to the Russell Fork watershed, before crossing into Kentucky near Breaks Interstate Park. That relocation will include building a 4-lane highway in the new stretch, replacing the 2-lane road originally built along the Levisa Fork.

the last highway improvements funded as part of Corridor Q are next to the Kentucky border

Source: Appalachian Regional Commission, Status of the Appalachian Development Highway System as of September 30, 2013

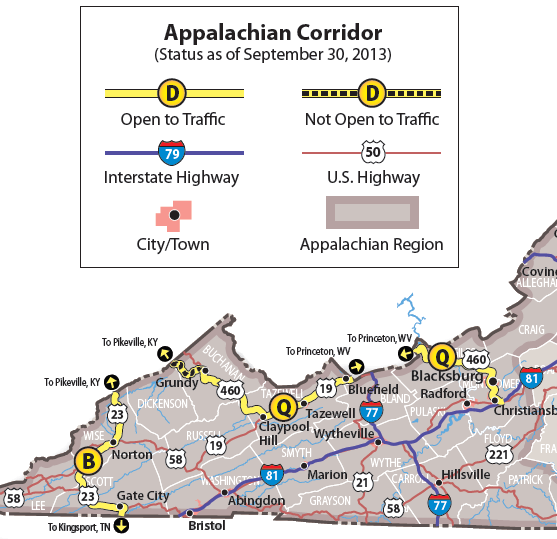

Corridor Q will shift US 460 westward (portion in red will be replaced)

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Coalfields Expressway: The Big Picture

US 460 links Roanoke and Blacksburg. The current four-lane road is an uncontrolled access highway lined by strip retail centers near Christiansburg. The drive between Roanoke-Blacksburg requires one hour.

In 1986, state and local officials proposed building a shortcut through Ellett Valley, with hopes of upgrading US 460 to become the proposed I-73. The mayor of Roanoke supportd building a 5.7-mile connector highway that would reduce travel time between Roanoke-Blacksburg by 30 minutes. That would help create at least the perception that Blacksburg/Roanoke were a single community sharing an airport and university, two essential elements required to attract new businesses to the area.

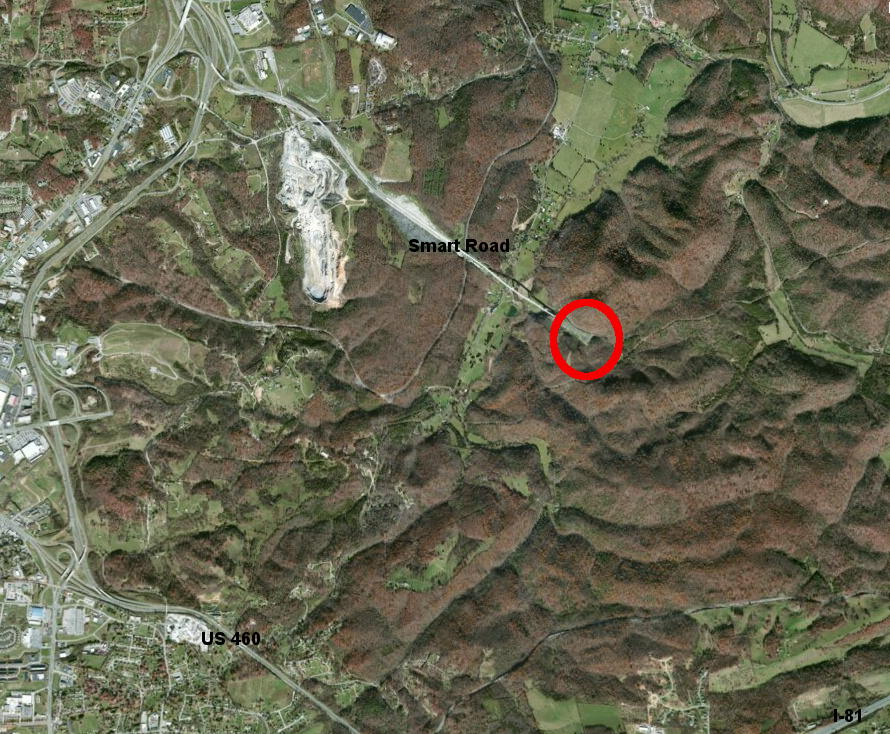

A 2.2 mile segment of the new road was funded in the 1990's under Federal earmarks for research and demonstration projects. VDOT built the "Smart Road," including the tallest highway bridge in Virginia (175 feet over Wilson Creek), but did not receive funding or approval to construct the segment through Ellett Valley to I-81. That planned-but-unbuilt segment would have disturbed a historic Confederate cemetery and a rare population of an endangered species, the smooth coneflower (Echinacea laevigata).

the Smart Road extension to I-81 was blocked in 1994 partly by the presence of the endangered smooth coneflower (Echinacea laevigata) on the preferred route

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Smooth Coneflower habitat

The Smart Road ended up being, at least for now, a two-lane dead end highway. Virginia Tech uses the Smart Road for Intelligent Vehicle Highway Systems research, assessing how high-tech cars and sensors in the roadway could reduce accidents and increase the number of vehicles that might travel together safely on highways, mimicking how birds fly together in a flock. Car manufacturers use that segment of road to test their newest models under varying conditions of fog, rain, snow, and different lighting conditions.

To improve local traffic, the US 460/I-81 interchange was upgraded to handle congestion created on football weekends at Virginia Tech, and a limited-access US 460 bypass was built around Christiansburg.1

the Smart Road is currently a dead end, and does not shorten the travel time between Roanoke's airport and Blacksburg's university

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

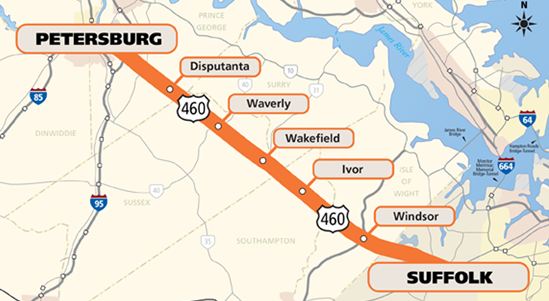

On the eastern end of US 460, the unusually-straight stretch between Suffolk-Petersburg was built as a 2-lane highway in the 1930's and widened to four lanes in the 1950's.2

It runs next to the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad. William Mahone built that railroad through the Great Dismal Swamp before the Civil War, with a 52-mile stretch of "tangent" track without a curve. Construction was difficult, but Mahone placed logs at right angles to form a roadbed that did not sink under the weight of the trains.

as shown in this 1859 map, the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was built first across the swampland northwest of Suffolk, and only later was a parallel road (now US460) constructed

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia, constructed in conformity to law from the late surveys authorized by the legislature and other original and authentic documents

Towns along the route evolved from railroad depots located at the distances where the steam locomotives would need a new supply of water. The depots were named by William Mahone and his wife Otelia. According to legend, they were influenced by romantic novels written by Sir Walter Scott, including Vicar of Wakefield, and "Disputanta" was chosen when the two could not agree on a name.3

US 460 was built as a straight-through-the-swamp highway between Suffolk-Petersburg

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, U.S. Route 460 Corridor Improvements Project

Trucks use that section of US 460 to go from the Port of Virginia to Interstate 95 and Interstate 85. Truck traffic was projected to increase after the Panama Canal was widened, based on the assumption that the Port of Virginia would attract additional container cargo ships to the Norfolk International Terminals, Virginia International Gateway (formerly known as the A.P. Moller/Maersk Terminal), or Portsmouth Marine Terminal in South Hampton Roads.

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) adopted a strategy to attract those container ships by enhancing the capacity to move containers inland via rail and truck through the "Heartland Corridor."

In 2012, VDOT entered into a public-private partnership with 460 Mobility Partners to replace a portion of existing US 460 between US 58 and the Interstate 295 interchange near Petersburg. The contract called for the private consortium to build a 55-mile long, four-lane highway parallel to US 460.

The new road would be used by 8,700 vehicles a day, roughly 10% of the daily traffic on I-64 at Williamsburg. Travelers between the port terminals and I-95 would bypass 10 stoplights and save 20 minutes, a 20% reduction.

Traffic would be reduced in the center of the towns of Disputanta, Waverly, Wakefield, Ivor, Zuni, and Windsor. Safety would be improved on a highway with a fatality rate nearly 300% greater than the Hampton Roads regional average.

The state planned to contribute $900 million from highway construction funds, while the Virginia Port Authority would contribute $250 million. In addition, 460 Mobility Partners would finance $250 million of the construction costs.4

To help the private investors recover their $250 million investment, the 55 miles of a new, parallel US 460 would have a $12 toll on trucks and a $4 toll on cars.

The state justified the $1.4 billion investment primarily by citing the expected increase in truck traffic after the Panama Canal was widened and more containers arrived at Hampton Roads terminals, but also by the increased capacity to evacuate South Hampton Roads if a hurricane struck. Blogger James Bacon said:5

The state was gambling that a new road would stimulate new buildings, new companies, and new jobs in southeastern Virginia. New development would generate sufficient taxes to justify investing $900 million in state funding. VDOT got two partners to subsidize the gamble, and each put $250 million in the pot to cover the total $1.4 billion in costs.

The Virginia Port Authority expected to generate enough extra business at its shipping terminals in Norfolk and Portsmouth to justify spending $250 million to upgrade a highway 15 miles west of the Elizabeth River. If trucks could get to I-95 faster via an upgraded US 460, then more ships would unload more containers at Norfolk International Terminals (NIT), Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT), and Virginia International Gateway (VIG).

The economic opportunity for 460 Mobility Partners was different. VDOT guaranteed that its private partner would be repaid. Both assumed that drivers paying tolls would generate enough revenue to repay the $250 million in bonds, plus a profit for the private investors.

The potential for increased economic development assumed that faster truck traffic on US 460 would spur construction of more distribution centers, processing the extra cargo to be delivered by container ships and transported on land via trucks. From a statewide perspective, speculative benefits from increased economic development in the US 460 presumed that the new development would not have occurred without the $1.4 billion investment in the road. If upgrading US 460 attracted economic development that would have occurred elsewhere in Virginia, then southeastern Virginia would see an economic uptick at the expense of some other rgion. There would be no net benefits to the entire state.

VDOT also assumed it could obtain permits from the US Army Corps of Engineers to fill wetlands Section 404 of the Clean Water Act. The proposed toll road crossed multiple streams and wetlands on the Coastal Plain. The Corps indicated it was reluctant to approve the loss of 480 acres of wetlands, which the Virginian-Pilot reported as potentially "the greatest destruction of permitted wetlands in Virginia since the creation of the Clean Water Act in 1972."6

The Corps supported an alternative with new construction limited to bypasses around the towns. The Federal agency notified VDOT that it was at risk, if the state proceeded to spend money on the route not yet approved by the Corps:7

The state expedited construction anyway, spending $300 million in 2012-2013. The Secretary of Transportation developed a public relations strategy to portray the Corps as trying to destroy southside Virginia along the existing 460 and the governor proclaimed the new US 460 to be his "number 1 transportation priority."8

A new governor (Terry McAuliffe) took office in 2014. He appointed a new Secretary of Transportation, replaced some members on the Commonwealth Transportation Board, and directed VDOT to reconsider plans to build the proposed 4-lane toll road. VDOT soon suspended work, citing the lack of the essential wetlands permit from the Corps of Engineers.9

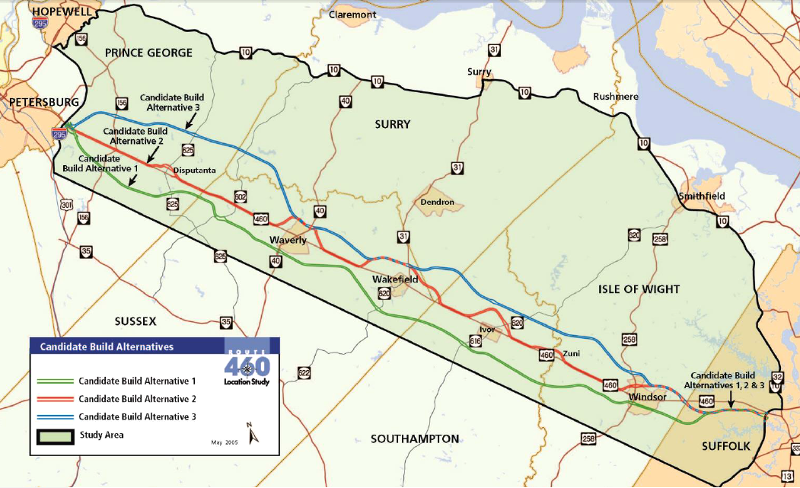

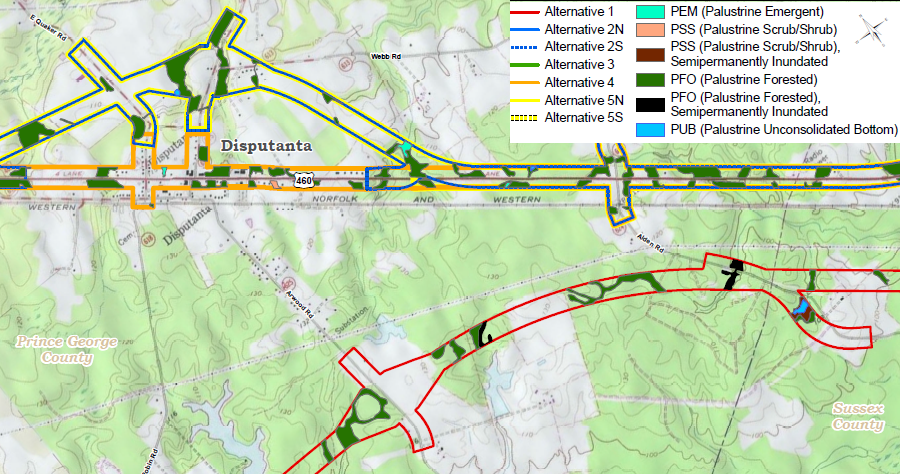

alternatives considered during Gov. McDonnell's administration for building a new road parallel to US 460

(green line south of current US 460 was alternative preferred by VDOT while red line avoiding most wetlands was Corps of Engineers preferred route)

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Presentation by Transportation Secretary Aubrey Layne and VDOT Commissioner Charlie Kilpatrick

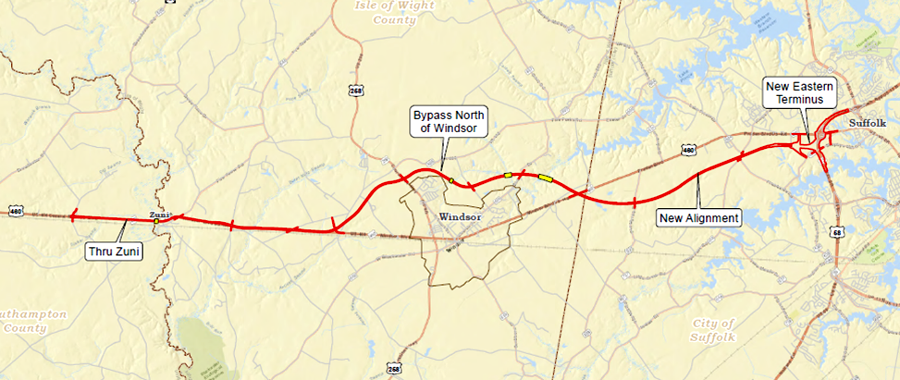

A Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), designed to identify the "Least Environmentally Damaging Practicable Alternative," was released later in 2014. It made clear that the proposal to build a new highway parallel to the current US 460 (the proposal preferred by VDOT under the previous administration of Gov. Bob McDonnell) would cause more environmental damage than any of the alternatives.

The Draft Supplemental EIS documented that the original toll road proposal would destroy 600 acres of wetlands and cost $1.8 billion. Adding safety improvements to the existing US 460 and building limited access bypasses around the towns (the alternative preferred by the Corps throughout the wetlands permit review process) would destroy just 91 acres of wetlands, at half the cost of building a new 4-lane highway.

The lower-impact, lower-cost alternatives offered less increase in capacity compared to building a new road, but the Draft Supplemental EIS indicated that the proposed new highway would be used by fewer vehicles than the 8,700 originally projected - just 5,000 to 6,000 vehicles daily, less than some subdivision roads in Fairfax County. The Draft Supplemental EIS did not identify a requirement to accommodate a dramatic increase in traffic. The Supplemental EIS made clear that a new 4-lane toll road was not the "Least Environmentally Damaging Practicable Alternative," and the Corps of Engineers would have difficulty approving the destruction of 500 additional acres of wetlands without a clear need for increased capacity.10

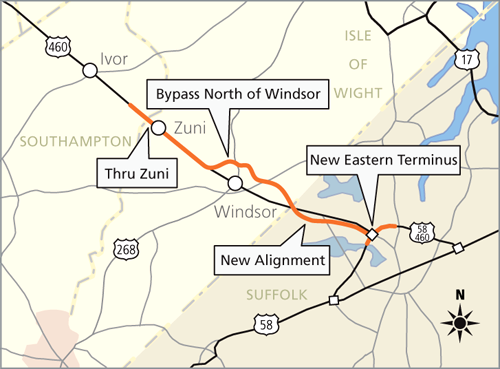

state transportation officials shifted policy in 2014 and supported building bypasses of towns on existing US 460 rather than a complete toll road, after governors changed and Federal officials signaled objections to wetlands destruction

Source: U.S. Route 460 Corridor Improvements Project - Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS), Alternative Route #2

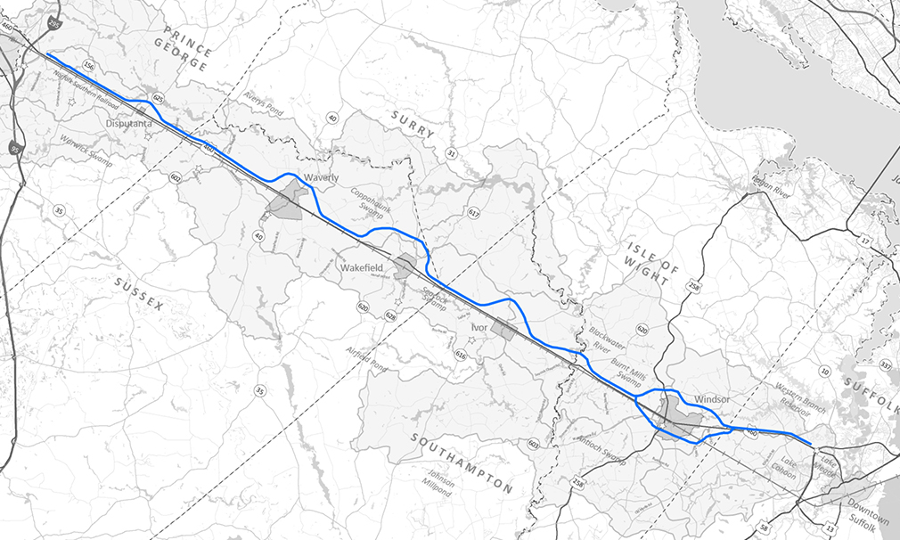

In 2015, the Commonwealth Transportation Board adopted a plan for VDOT to build a new four-lane divided highway for only 17 miles (at the eastern end of US 460, between the US460/US58 interchange in Suffolk to just west of Windsor), convert existing US 460 into a four-lane divided highway west to Zuni, and build a new bridge over the Blackwater River there.

The cost of that new proposal was only $400 million, about 1/3 of the expected cost of building 55 miles of new highway. The new proposal would destroy 10% of the wetlands that would have been affected under Gov. McDonnell's highway plan, just 52 acres of wetlands instead of 600 acres.11

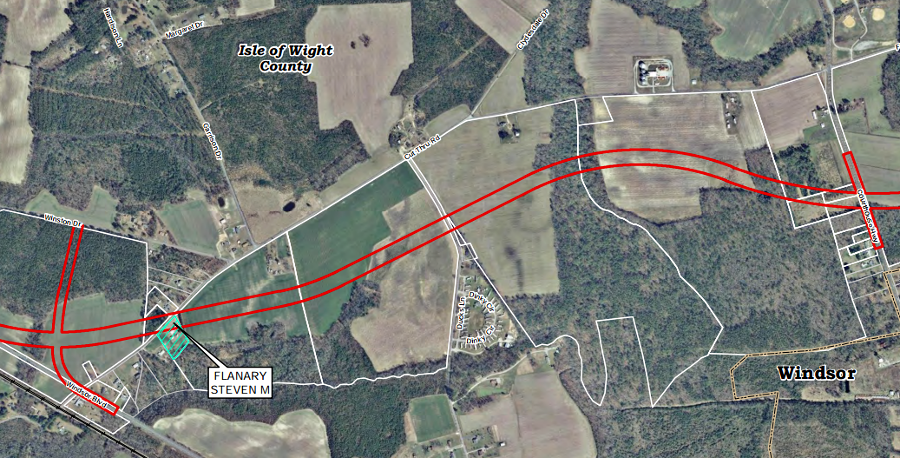

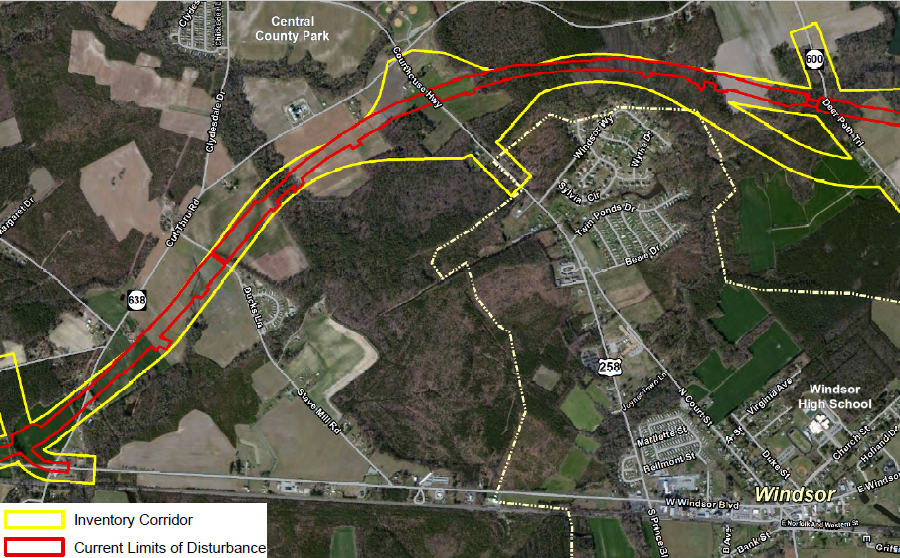

VDOT identified each parcel of private property that must be acquired in order to build a new portion of US 460

Source: U.S. Route 460 Corridor Improvements Project, Preferred Alternative Corridor Displacements

In April, 2015, VDOT formally cancelled the contract with US 460 Mobility Partners and sought to recover some of the $256 million paid to the private company.12

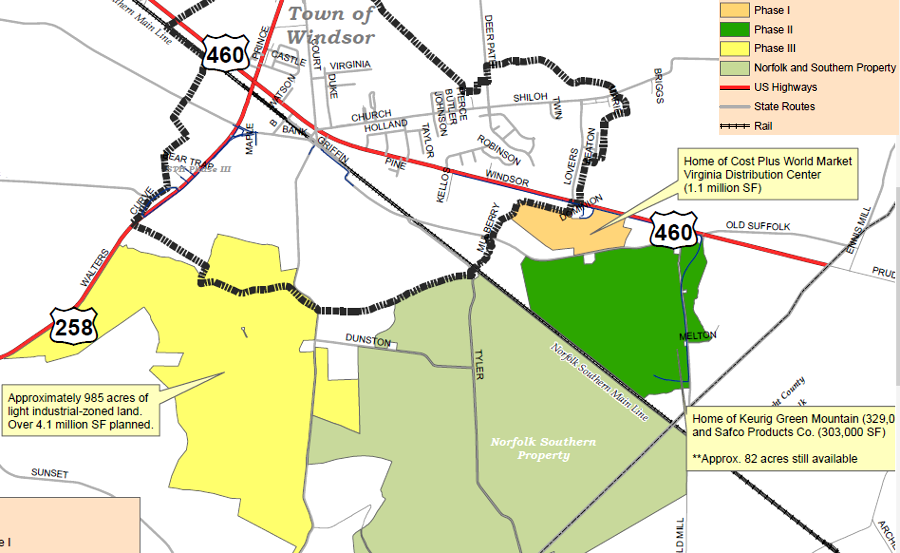

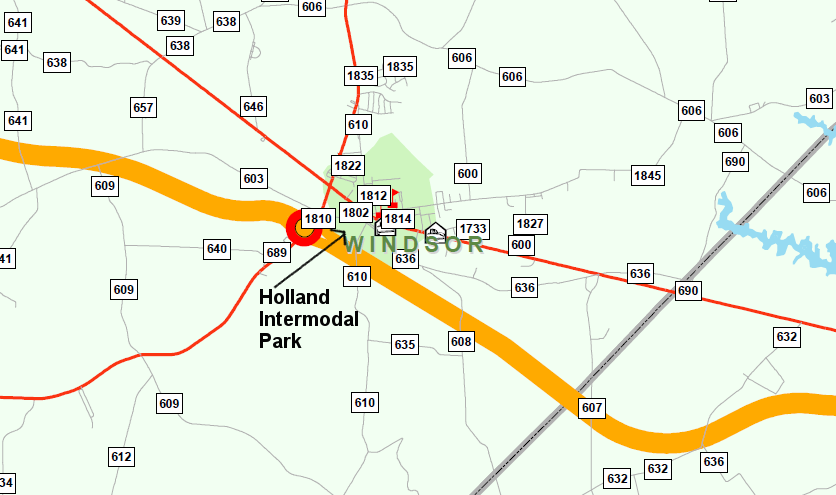

Town of Windsor and Isle of Wight County officials were not pleased by the scaled-down plan. The Isle of Wight County Industrial Development Authority had spent $17 million to build the Shirley T. Holland Intermodal Park south of town, expecting VDOT to complete a new highway parallel to existing US 460 with a bypass south of Windsor.

Holland Intermodal Park is south of current US 460

Source: Isle of Wight County, Shirley T. Holland Intermodal Park - Phase II Conceptual Layout

The intermodal park would service distribution warehouses for merchandise moving through the Port of Virginia terminals in Portsmouth/Norfolk. As originally proposed under Gov. Bob McDonnell and his Secretary of Transportation Sean Connaughton, the new US 460 would have provided improved access to the Shirley T. Holland Intermodal Park. That state government investment in a new road was expected to spur new construction and new tax revenue for Windsor.

VDOT's original route was a new 460 south of Windsor, providing direct access for Holland Intermodal Park

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Realignment map with secondary roads

The next governor, Gov. Terry McAuliffe, altered the path of the new road. His Commonwealth Transportation Board included many members who had voted for the initial US 460 replacement proposal, but the new governor recognized that political pressure on the Corps of Engineers would result in a permit to destroy wetlands.

The revised proposal re-routed US 460 between Suffolk and Windsor, while upgrading the existing road further west. That route reduced the impact on natural resources, as well as construction costs.

the 2015 revised proposal cut new road construction from 55 miles to just 17 miles, minimized wetlands impact by 90%, and reduced costs by over 60%

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), VDOT, FHWA And U.S. Army Corps Of Engineers Make Progress On Environmental Work To Improve U.S. 460 Corridor In Southeastern Virginia

The new route included a bypass north of Windsor. That reduced the speculative potential of the town's investment in the industrial park south of town.

under Gov. McAuliffe, the revised plan for US 460 included a bypass north of Windsor

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Route 460 Project Southeast Virginia

The new route north of Windsor also affected local farmers. One, whose farm would be bisected by the adjusted alignment, complained:13

The impacts on wetlands had dropped down to 35 acres. Town of Windsor officials remained opposed to the bypass for economic reasons, and the Southern Environmental Law Center opposed the proposal for environmental reasons. It challenged the state's application to the US Army Corps of Engineers for a permit, required by Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, to dredge and fill wetlands.

under Gov. McAuliffe, the Virginia Department of Transportation revised the proposal to replace US 460, but still included building a new 4-lane divided highway from Suffolk to west of Windsor

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), About Route 460 Project Southeast Virginia

The Southern Environmental Law Center argued that building bypasses through wetlands to address the low level of traffic congestion on US 460 was not the "least environmentally damaging practicable alternative." The environmental group proposed widening the existing road, rebuilding US Route 460 in its present alignment. In Windsor, it proposed a continuous two-way left turn lane rather than VDOT's proposed 16-foot wide raised median, which forced drivers to make U-turns at intersections in order to to access a business on the other side of the highway.14

the Southern Environmental Law Center proposed expanding rather than replacing US 460, mitigating impacts but maintaining the route through Windsor

Source: Southern Environmental Law Center, Concept Plan for Modification of Alternative 4 US Route 460 Windsor, Virginia

The Corps issued the permit to VDOT in later 2016, granting the state agency the authority to dredge or fill 35 acres of wetlands.15

analysis of alternatives documented that 85% fewer acres of wetlands would be affected by construction of bypasses rather than building a new 4-lane highway

Source: U.S. Route 460 Corridor Improvements Project - Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS), US Rte 460 Natural Resources Technical Report - Photointerpreted Inventory Corridor Wetlands (Figure 4.4-2)

However, the public-private partnership project died in 2015. The Secretary of Transportation negotiated a deal with the private partner. The company received $260 million despite doing no construction work, but the state eliminated potential claims for an additional $103 million. By that time, estimated costs for the expressway had reached $1.8 billion.

The boondoggle led to passage of HB2 and creation of what is now know as the SmartScale ranking system. The Commwealth Transportation Board receives a ranking of proposed transportation projects, based an analysis of costs and benefits, before approving projects. Projects are granted full funding, or no funding, based on the priority assigned in the SmartScale process.

The 2017 SmartScale ranking of the project, used by the Commonwealth Transportation Board to prioritize funding for different projects, was so low for US 460 widening that the Virginia Secretary of Transportation announced:16

That decision left just one option for expanding the highway and building bypasses. The General Assembly still could exclude the project from the SmartScale ranking process and direct funding to it, no matter how poorly it ranked in cost-effectiveness compared to other projects considered for the Six Year Improvement Program of the Virginia Department of Transportation.

The option of excluding a project from SmartScale assessment was proposed in 2017 by advocates for the Coalfields Expressway. US 460 west of Christiansburg is also Corridor Q in the Appalachian Development Highway System (ADHS). The Coalfields Expressway project upgraded the far western edge of US 460/Corridor Q near Breaks Interstate Park, to link to a relocated portion of US 460 in Kentucky.

Corridor Q 460 Connector Phase I bridge under construction near Breaks Interstate Park

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Coalfields Expressway & ADHS Corridor Q

The tallest highway bridge in Virginia, over 250 feet high, was constructed as part of that link. A clue to how the US 460 Corridor Q Connector was a political priority, rather than integrated with other transportation planning, was the completion date of the bridge in 2015. That was five years before Kentucky constructed its portion of the connector road; the highest bridge in Virginia bridge sat unused during that time.

Building the Virginia portion south of the bridge to reach US 460 was delayed even longer. Until that section is completed, traffic crossing the four-lane bridge will have to take a sharp left turn to reach VA 80, a twisting mountain road with just two lanes.17

the four-lane bridge oner Grassy Creek connects to just two-lane VA 80 in Virginia, until the rest of the Corridor Q 460 Connector is completed in Buchanan County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The $5+ billion Coalfields Expressway might jump-start economic development in Southwest Virginia, but offered few benefits for congestion relief and other factors ranked in the SmartScale process. Legislators from the region sought to exempt the project from comparison with others in Hampton Roads, Richmond, Northern Virginia, and elsewhere which offered a higher return on investment for state transportation funding.18

the bold orange line identifies the portion of US 460/Corridor upgraded as part of the Coalfields Expressway project (bold green line)

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Coalfields Expressway & ADHS Corridor Q

US460 between Petersburg-Norfolk follows a route that dates back to colonial times

(note cardinal directions - south is towards top of sketch)

Source: Library of Congress, Sketch of the road from Fredericksburg to Norfolk in Virginia (1781)