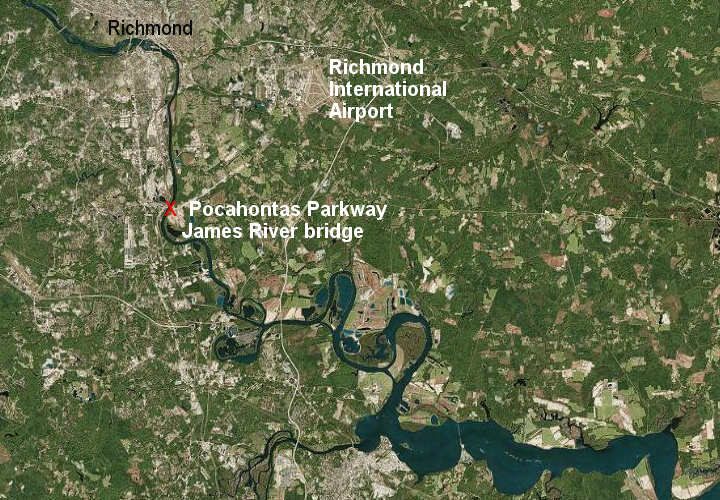

the Pocahontas Parkway bridge across the James River was built high enough to permit ship traffic to pass below without opening a drawbridge

Map Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Bridge Gallery

the Pocahontas Parkway bridge across the James River was built high enough to permit ship traffic to pass below without opening a drawbridge

Map Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Bridge Gallery

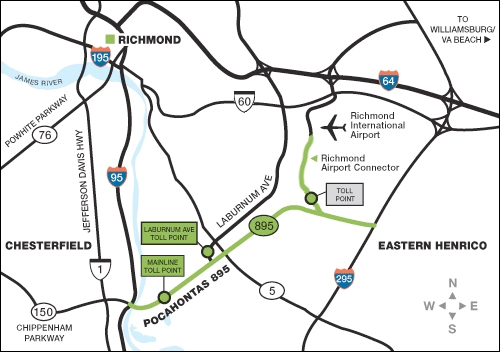

In the 1990's, the Virginia Department of Transportation lacked the funds to build the missing piece that would create a southern bypass around Richmond, the 9-mile link between Chippenham Parkway to I-295. The Henrico County Industrial Development Authority was asked to finance the road, including a new bridge across the James River, but that organization judged the project to be too great a financial risk.1

The General Assembly, at Governor George Allen's urging, passed the Virginia's Public Private Transportation Act of 1995 to attract private investors to finance public roads. Fluor Daniel/Morrison Knudsen then created the Pocahontas Parkway Association, signed a contract with the state in 1998, and found investors for $354 million in tax-exempt bonds to pay for construction. In addition to the private funds, the project used some Federal and state funding - $9 million in Federal funds used earlier for roadway design, plus an $18 million loan from the Virginia State Infrastructure Bank.2

The Pocahontas Parkway was the first construction project implemented under Virginia's Public-Private Transportation Act of 1995 (PPTA). The state owned the road, but granted a long-term lease to the Pocahontas Parkway Association. The Pocahontas Parkway Association was organized as a nonprofit so it could issue $354 million in tax-exempt bonds.

Fluor Daniel/Morrison Knudsen profited from the construction project to build the Pocahontas Parkway. The Pocahontas Parkway Association sold tax-exempt bonds as a non-profit organization and was not expected to generate profits from operating the facility. The tolls paid by drivers were expected to generate the revenue required to repay the private investors who had bought bonds to fund initial construction, and to generate sufficient annual revenue for highway operations/maintenance.3

the 8.8 mile Pocahontas Parkway and 1.6 mile Airport Connector road were expected to make a profit from customers living in new suburban developments in southeastern Henrico County, plus customers going to the Richmond airport

Source: Using Pocahontas 895

The Pocahontas Parkway Association opened the Pocahontas Parkway in 2002. The decision to build a toll road affected plans to label the highway. It was built to interstate standards and called I-895 in the planning documents, but in 2002 the Federal government would not authorize new interstate highways that used Federal funding (in this case, $9 million) and charged tolls.

Pocahontas Parkway was labelled State Route 895, even though primary roads in Virginia have route numbers below 600 and secondary roads are numbered 600 or higher. Virginia has kept open the possibility that the I-895 label can be applied, once the Federal government authorizes new toll roads to be added to the interstate system. Pocahontas 895 is the current shorthand label.4

The Pocahontas Parkway was built with the anticipation that enough customers would pay tolls so the Pocahontas Parkway Association could repay the bonds and generate a profit. Traffic was expected to grow due to new suburban subdivisions southeast of Richmond (including 2,770 housing units at Tree Hill and 3,209 homes at Wilton-on-the-James), and due to increased passenger use of Richmond International Airport after Southeast made it a hub.5

Fluor Daniel/Morrison Knudsen proposed building only one bridge across the James River initially, and waiting for traffic demand to grow before constructing the second bridge and associated ramps to I-95. VDOT required full construction, but did allow omission of the ramp for southbound traffic on I-95 to access the road and delay of the 1.6-mile Richmond Airport Connector.6

to reduce construction costs, the ramp that would have allowed southbound I-95 traffic to access the Pocahontas Parkway was never built

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Drewry's Bluff 7.5x7.5 topographic map (2013)

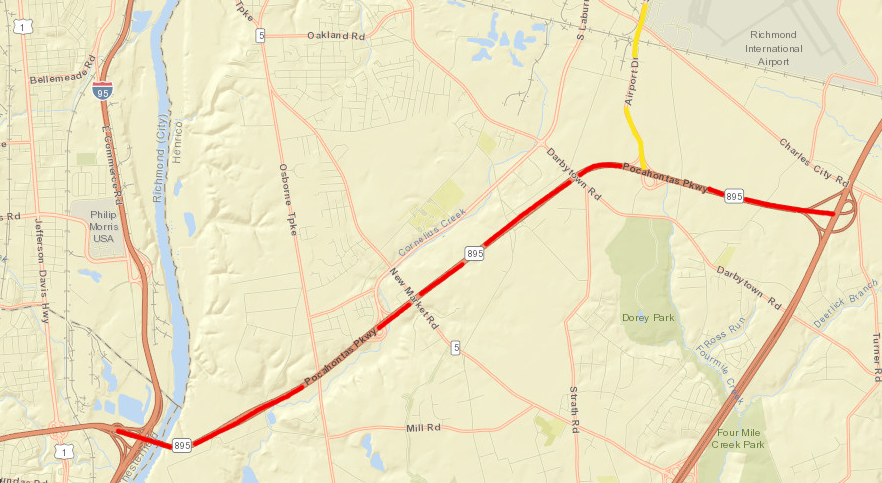

Projections of traffic on the road turned out to be excessively optimistic; only 42% of predicted levels in the year after opening, too low to repay VDOT for its maintenance costs. By 2004 the Pocahontas Parkway Association was looking at bankruptcy. Transurban, an Australian firm, offered to refinance the bonds, repay the $18 million loan from the Virginia State Infrastructure Bank, build the connection to the airport, and assume responsibility for future maintenance.

In 2006, Transurban got a 99-year lease from VDOT, bought all rights from the Pocahontas Parkway Association, and paid off the state's $18 million debt. Thinking optimistically, the Transurban-VDOT contract included provisions for the state to get a percentage of the revenue generated by tolls once the rate of return on the private investment exceeded 6.5%.

That Australian firm obtained a $150 million Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) loan in 2007 to finance upgrades to the tolling system, pay off some debt, and build the $50 million Richmond Airport Connector. The extension to the airport, required in the 99-year lease agreement negotiated under the authority in the 1995 Public Private Transportation Act, was completed in 2011.

The projected costs of the Richmond Airport Connector exceeded toll revenues from incremental traffic that would be generated, but Transurban expected to offset the losses with the financial advantages of the TIFIA loan. One assessment of the extension concluded the project was not cost-effective:7

the Pocahontas Parkway (red) opened in 2002 and the Richmond Airport Connector (yellow) was built in 2011

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Transurban did not make a profit from its investment in the Pocahontas Parkway. Traffic grew to the point that by 2006, tolls were adequate to cover operations and maintenance costs. However, there were not enough vehicles paying tolls to generate enough revenue to repay the capital investment. The 2008 recession stopped banks from financing speculative home construction, and the anticipated traffic to new Henrico suburbs did not develop.

In 2012 Transurban wrote off its $130 million investment. In 2013, the company notified the consortium of European banks who had provided financing that their $300 million loan would not be repaid.8

At that point, the Virginia Department of Transportation became responsible for managing the Pocahontas Parkway. The Virginia Secretary of Transportation portrayed the bankruptcy and transfer of ownership to the banks as a Public-Private Transportation Act success:9

the Pocahontas Parkway, seen from I-95 headed north

In 2014, VDOT chose to contract out the operations and maintenance of the road and signed a five-year contract with DBi Services, Pennsylvania firm. Local law enforcement officers and the Virginia State Police remained responsible for speed and other enforcement. The private firm described its responsibilities for operating Pocahontas 895 as follows:10

In 2016, the Spanish company Globalvia acquired the contract for collecting tolls and maintaining the nine-mile road.11

The Pocahontas Parkway was an engineering success but a financial failure. Two separate private sector companies were unable to pay the bills for the Pocahontas Parkway. The financial failure of Virginia's first project funded under the Public Private Transportation Act of 1995 revealed clearly that "if you build it, they will come" expectations can be unrealistic.

slower-than-expected suburban development in southeastern Henrico County led to the financial failure of the Pocahontas Parkway

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

VDOT treated the failure as an anomaly rather than as a warning. The agency continued to create "rosy scenario" projections on how much development could be stimulated by a new road. The state agency continued to use optimistic assumptions to justify projects, including a proposed new road parallel to US 460 between Suffolk-Petersburg and the propose Bi-County Parkway in Prince William-Loudoun counties.

The private sector learned a different lesson, and negotiated better financial security with the state before committing to future projects. Investors arranging other Public Private Partnership (P3) deals with VDOT forced the state to provide a higher percentage of financing.

US 460 Mobility Partners, the private investor in the $1.4 billion US 460 project in southeastern Virginia, committed only $250 million for construction. The state assumed all the risks for getting wetlands permits from the US Army Corps of Engineers, and authorized construction planning despite indications from the Corps of Engineers that the project would not be permitted.

The wetlands permit for the proposed parallel road was not issued, but the private corporation was still paid for its efforts. Not a single inch of highway was constructed by the private partner, but the Public Private Partnership for the US 460 project cost the state $250 million.12

Transurban's investment in the Pocahontas Parkway was a short-term financial loss, but it was the company's first project in the United States.13

the Pocahontas Parkway bridge across the James River

Map Source: Federal Highway Administration, Introduction to Public-Private Partnerships (P3s) - Presentation

The Pocahontas Parkway also helped the foreign firm build a positive relationship with VDOT. VDOT later awarded Transurban the rights to build the I-495 Express Lanes and I-95 High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes in Northern Virginia.

The state assumed a substantial part of the financial risk in the Public Private Partnership for building the I-495 Express Lanes. Transurban financed only 75% of the construction cost.

To reduce traffic congestion, VDOT required that cars with at least three passengers on the I-495 Express Lanes will not pay any toll. Transurban feared an expansion of carpooling would result in too many toll-free cars on the I-495 Express Lanes, and the investment would no longer generate sufficient revenue. To ensure the private company would commit to the Public Private Partnership, VDOT agreed to pay Transurban 70% of the lost fees from carpoolers once "free" cars exceeded 24% of the traffic.14

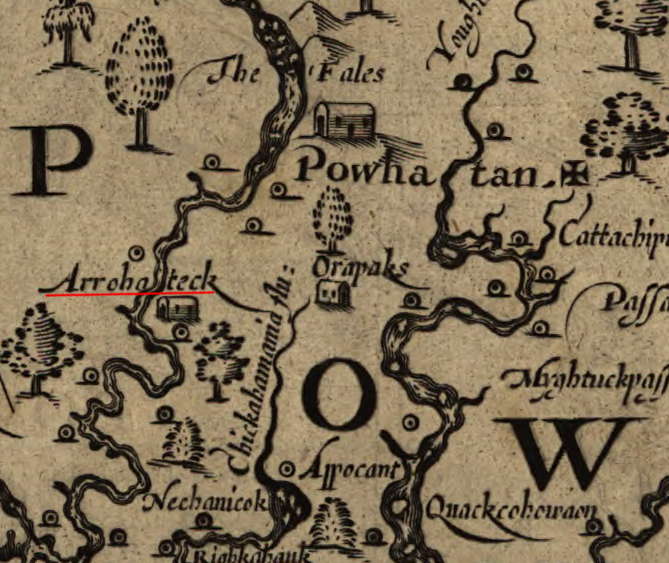

the Pocahontas Parkway crosses the James River thirteen miles downstream of the Fall Line ("the Fales") at Richmond, where the Native American town of Arrohateck was located in 1607

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

Pocahontas Parkway interchange with I-95

Source: Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), The Role of PPPs In Addressing Congestion

the Pocahontas Parkway interchange with I-95

Map Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Bridge Gallery