Norfolk Municipal Airport, prior to 1945

Source: Boston Public Library, Tichnor Brothers Postcard Collection, Municipal Airport, Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk Municipal Airport, prior to 1945

Source: Boston Public Library, Tichnor Brothers Postcard Collection, Municipal Airport, Norfolk, Virginia

Commercial flights began in Norfolk in the 1920's, starting with service from a field on Granby Street to Washington and Philadelphia. The initial company offering passenger service folded, but starting in 1929 Eastern Airlines starting flying twice each day to Richmond.

During the Great Depression, scheduled air travel stopped for five years. It restarted in a new location, since the US Navy was concerned about conflicts with military flights using Norfolk Naval Air Station.

The city converted Truxton Manor Golf Course into Norfolk Municipal Airport, which opened in 1938. The first airline, which ended up becoming part of United Airlines, used the golf clubhouse until the airport's first purpose-built passenger terminal was completed in 1940.

The airport has expanded at that site. It was renamed Norfolk Regional Airport in 1968, then Norfolk International Airport in 1976. It added federal inspection facilities that year.

Despite the name, Norfolk International Airport had no scheduled flights to international locations after 2001 when the effects of the 9/11 terrorist attacks caused Air Canada to cease flying from the airport. However, in 2024 construction started on an international arrivals area with a US Customs and Border Protection inspection facility plus a Global Entry processing center. Breeze Airways announced in 2025 that it would start flying once a week to Cancun in 2026.

aeronautical chart for area including Norfolk International Airport (ORF)

Source: SkyVector

The airport is governed by the Norfolk Airport Authority. Commissioners are appointed by the City Council of Norfolk; no other political jurisdiction in Hampton Roads has an official vote.1

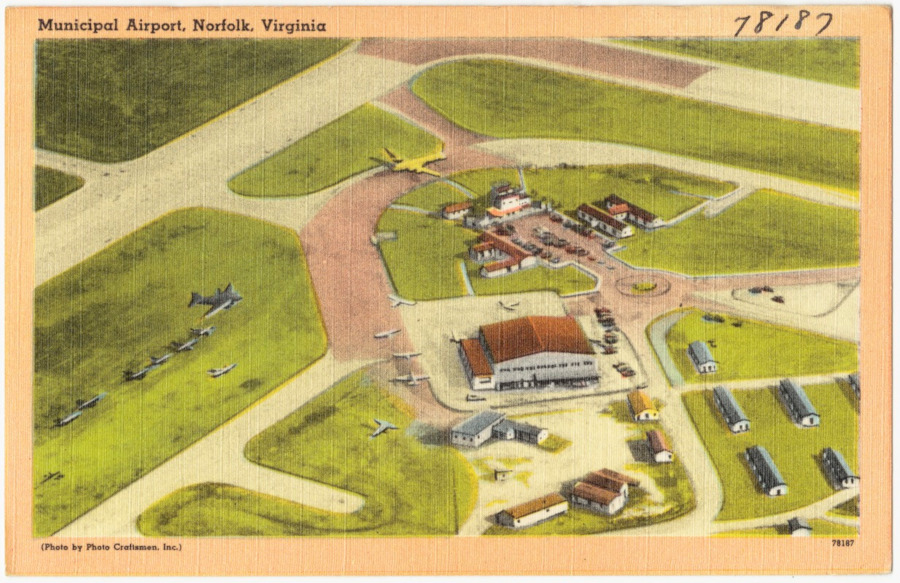

Passenger traffic at the Norfolk International Airport peaked in 2005 and then dropped 20% between 2005-2013. In 2014, the number of travelers (counting both enplanements and deplanements) dropped below 3 million. That was the lowest use of the airport since 2001.2

between 2007-13, the number of passengers getting on a commercial flight (enplanements) at Norfolk International Airport declined by 16%

Source: Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Passenger Boarding (Enplanement) and All-Cargo Data for U.S. Airports

The Norfolk Airport Authority still proposed building a second runway for $300 million. The mayor of Virginia Beach advocated expansion based on the "build it and they will come" assumption, hoping new runway capacity would increase the number of flights and get an airline to offer flights from Norfolk to Europe.

However, local officials did not make it a priority to provide bus or light rail access to the airport in order to increase traffic. Almost 90% of airports with scheduled commercial passenger service have bus or rail access, but Norfolk (and Richmond) do not. One advantage of limiting public transportation: the airports gain more revenue from their parking lots.3

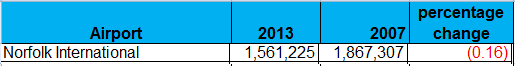

In 2016, half of the remaining major airlines (American, Delta, United, and Southwest) flew out of Norfolk. The airline hub-and-spoke system, used to concentrate passengers and maximize profits, provided access from Norfolk to every airport in the world offering commercial passenger service.

Non-stop destinations were limited to airline hubs east of the Mississippi River (Miami, Orlando, Atlanta, Charlotte, Washington DC, Philadelphia, New York, Detroit, Chicago) plus two cities further west, Houston and Dallas. Norfolk did not generate a sufficient number of passengers going to a single destination to justify direct flights to additional destinations, though community leaders constantly seek more direct flights.

Norfolk's airport offered non-stop service as far west as Dallas and Houston in 2016, but all other non-stop destinations were east of the Mississippi River

Source: Norfolk International Airport, Route Mapper

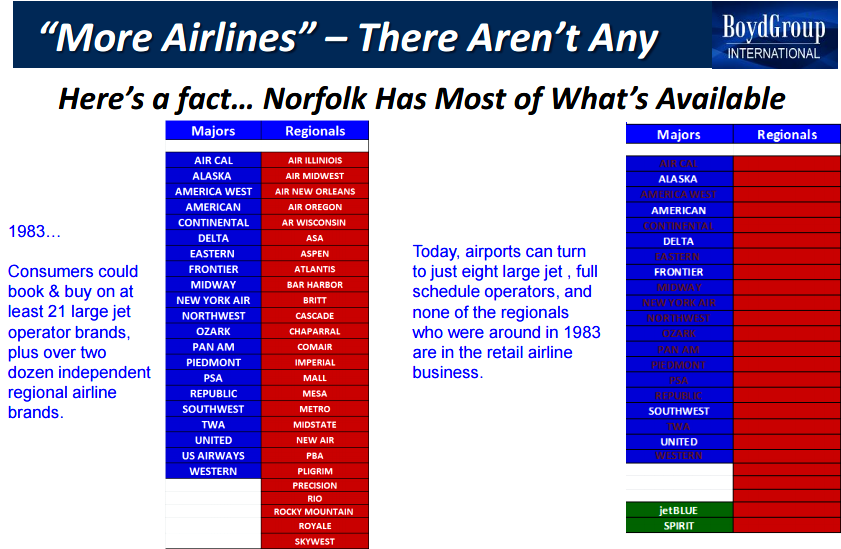

Norfolk's opportunity to attract any of the remaining airlines was poor, though JetBlue was a candidate for adding a route to Boston. An aviation consultant told the Hampton Roads Chamber of Commerce in 2016:4

in 2016, aviation consultants predicted passenger growth from increasing flights on existing carriers servicing at Norfolk's airport, not from attracting more airlines

Source: Boyd Group International, Hampton Roads Air Service Forum (April 12, 2016)

Nonetheless, in 2017 Allegiant Airlines began to fly to several destinations in Florida. In 2018 Norfolk was able to recruit a sixth airline, joining United, Delta, American, Southwest and Allegiant. Frontier, another ultra-low-cost carrier like Allegiant, offered flights to Denver and Orlando, then announced plans to expand to Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Tampa.

Allegiant Airlines began to fly out of Norfolk in 2017, and Frontier in 2018

Source: Norfolk International Airport, Where We Fly

When Southwest announced plans to offer non-stop flights to San Diego on summer weekends in 2019, Norfolk got its first direct link to the West Coast. Airport officials noted that the airline had tested demand with seasonal service to Denver in 2016, then expanded the number of flights. Incremental expansion by existing airlines offered the airport a way to grow service, without having to offer incentives to attract a new airline.

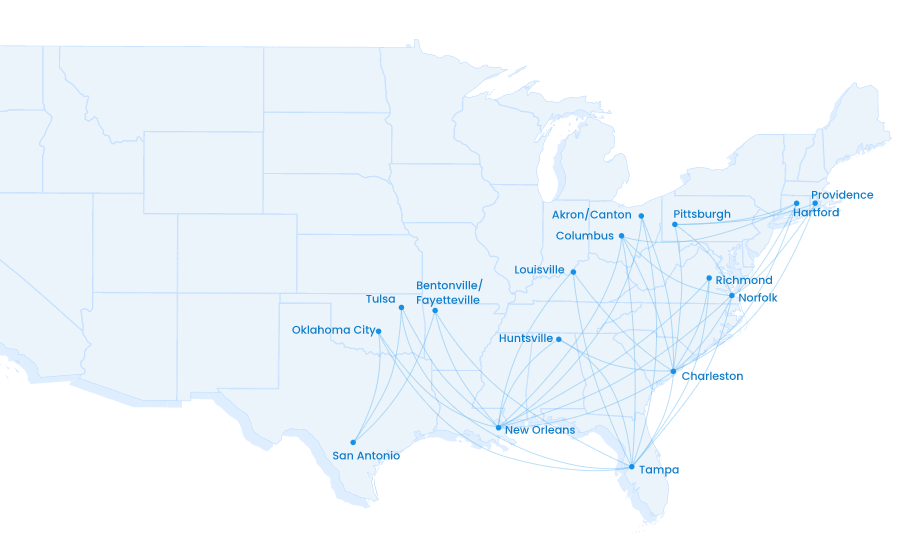

However, after the COVID-19 pandemic, Norfolk was successful in recruiting a new low-cost airline. Breeze Airways also chose to place its operations center in the city. Breeze planned operations initially from 16 cities, and chose Richmond and Norfolk at the start. Flights were scheduled from Norfolk International Airport (ORF) to seven cities, six of which were new non-stop destinations:5

- Charleston, SC

- Tampa, FL

- New Orleans, LA

- Columbus, OH

- Hartford, CT

- Pittsburgh, PA

- Providence, RI

Breeze Airways announced plans to build an operations center and fly out of Norfolk (and Richmond) in 2021

Source: Breeze Airways

Despite the name and its location next to the Atlantic Ocean, Norfolk International Airport had no direct flights to any international destinations. The regional population is too small to justify flights in large, ocean-crossing airplanes to Europe. Norfolk is essentially in a population cul-de-sac at the end of I-64. On the east is the Atlantic Ocean, rather than residents who might use Norfolk's airport.

In 2002 and again in 2012, the airport proposed building a second runway and close the 4,875-foot crosswind runway. The 2002 justification for a second runway was to accommodate increasing demand, but the 2008 recession appears to have triggered a permanent reduction in the number of commercial flights. The 2012 justification was to provide safety and redundancy. Eliminating the crosswind runway would reduce the risk that a crash of a small general aviation plane might affect people on the ground.

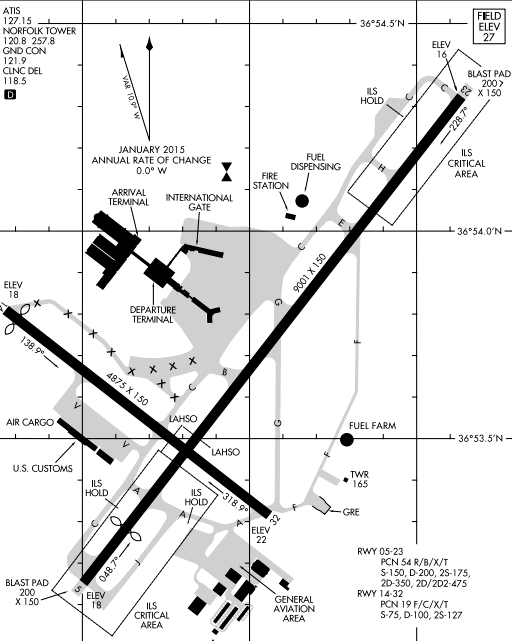

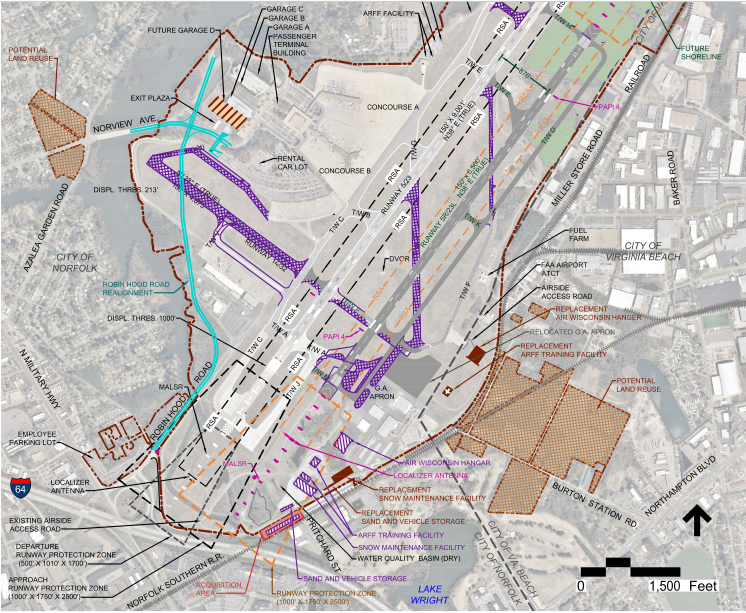

Norfolk International Airport (ORF) has only one 9,001-foot long runway suitable for scheduled passenger jets. The proposed expansion would add a new 6,500-foot runway parallel to the main runway.

The 4,875-foot crosswind runway was used by small planes under certain wind conditions. Less than 1% of takeoffs and landings used that runway, built perpendicular to the main runway. Safety issues centered on the crosswind runway, because it lacked the 1,000-foot safety zones required by Federal regulations in case of a crash.

the Norfolk International Airport (ORF) has one 9,001-foot runway, plus a perpendicular 4,875-foot runway used occasionally during crosswinds until 2025

Source: Federal Aviation Administration, Airport Diagram - Norfolk International Airport (ORF)

Adding a second runway would increase airport reliability as well as safety. A second runway could facilitate continued operations during future repaving, minimizing the potential that Norfolk International Airport (ORF) might have to close down and block all scheduled passenger traffic for several months. Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport (PHF) has two runways, and Richmond International Airport (RIC) has three.

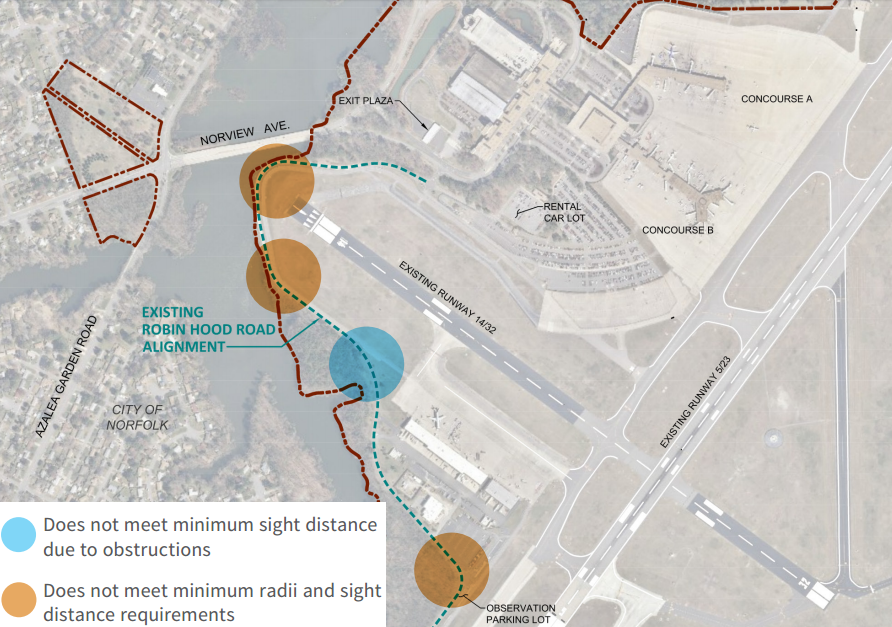

Robin Hood Road, the secondary access road to Norfolk International Airport (ORF), creates safety deficiencies

Source: Wayback Machine - Norfolk International Airport (ORF) Environmental Impact Statement, Informational Display Boards

In 2016, the Federal Aviation Administration rejected the request for Airport Improvement Program funding to build a parallel runway and relocate the secondary, crosswind runway. The Federal agency determined that the $300 million in costs were too high compared to the benefits, even though Delta, United, Southwest and American airlines had added flights and passenger traffic was nearing 3 million/year again for the first time since 2014.

The Norfolk Airport Authority then closed the shorter crosswind runway in late 2016 for commercial flights. The airport had a waiver from Federal safety regulations regarding 1,000-foot safety zones while the grant application was being considered, but the waiver expired after rejection of the grant.

The crosswind runway was reopened for general aviation flights after being repainted to a shorter length. Airport consultants described it as only "marginally useful" because it was not able to serve as a "release valve" for accommodating projected demand.

The $65 million rehabilitation of the primary runway was completed between 2018-2024. The 1,500-foot sections on either end of the runway were repaved as part of the upgrade.6

The crosswind runway was repainted to be 3,900 feet long and define an adequate safety zone, then re-opened in 2017. Airport officials continued to express the need for a second parallel long runway. They claimed that around the year 2030, the long runway would need to be torn up and replaced. Without a second runway to maintain existing operations, Norfolk International Airport (ORF) would have to stop commercial passenger flights.

After the rejection, airport officials found a way to repave the long runway without completely closing down. In 2018, the 6,000' of asphalt in the middle of the runway was repaved at night. Airlines had to cancel all flights between 12:15am-5:15am for 12 weeks. Any plane that arrived late during the repair time would have to divert to land at Richmond, with passengers taken by bus to Norfolk. Replacing the 1,500' of concrete at either end was scheduled for the summer of 2019.7

the proposed second runway at the Norfolk International Airport (ORF) included eliminating the shorter crosswind runway

Source: Wayback Machine - Norfolk International Airport (ORF) Environmental Impact Statement, Informational Display Boards

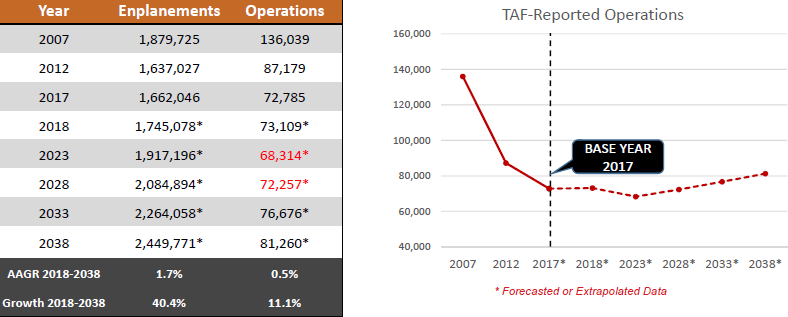

Airport officials drafted a new Master Plan for the airport in 2018. It projected that passenger traffic ("enplanements") would increase 40% over the next 20 years, but the number of takeoffs and landings ("operations") would increase by only 11%. Larger airplanes were predicted to carry more passengers.

The Master Plan continued to propose a second runway. However, in 2019 the US Navy formally objected to constructing the additional runway at Norfolk International Airport (ORF). It claimed the runway would require relocating helicopter training operations for Naval Special Warfare Command, which was based at Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek-Fort Story. The Navy threatened to move military personnel away from Hampton Roads, an action which would impact the local economy, because:8

Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) forecast of aircraft operations at Norfolk International Airport (ORF)

Source: Norfolk International Airport, Master Plan Update Public Meeting #1 (May 30, 2018)

The objection to inclusion of the new runway in the 20-year master plan caught Norfolk International Airport officials by surprise. The airport and the Navy had signed a Memorandum of Understanding in 1971 authorizing overflights of the military base at Little Creek, and including plans for a parallel runway that would require filing in a part of Lake Whitehurst. More recent planning reduced the length of the runway and the impacts of the lake, without increasing impacts on the military base.

In response to the Navy's objections, the former chair of the Norfolk Airport Authority Board of Commissioners emphasized:9

Neighbors living near the airport had a different objection. Airport staff used vehicle horns, propane cannons, firecrackers and other pyrotechnics and noisemakers to keep birds away from the planes that were landing and taking off. The airport's Wildlife Hazard Management Plan included noises designed to be obnoxious to the birds, but they also had the effect of disturbing people in nearby houses. Neighbors complained about "20 bangs an hour all day long."

Despite the intentional disturbance, there were still plane-bird collisions at the airport. None have caused a crash, but a bald eagle nesting at the adjacent Norfolk Botanical Garden was killed in 2001 by a US Airways flight jet as it landed. The eagle had three eaglets in her nest at the time, and had attracted many viewers on the garden's Eagle Cam.

Wildlife biologists concluded that her mate, nicknamed Dad Norfolk, would be unable to feed all three until they fledged. The eaglets were removed from their nest and transported across the Blue Ridge to The Wildlife Center of Virginia in Augusta County. They were released back into the wild after they had matured. Local residents continued to monitor Dad Norfolk, who had a distinctive dot on his eye, as he found new mates and built new nests over the next decade.10

the first terminal at Norfolk Municipal Airport

Source: Boston Public Library, Tichnor Brothers Postcard Collection, Municipal Airport, Norfolk, Virginia

Passenger traffic recovered quickly from the COVID-19 pandemic; the 4.5 million passengers in 2023 set a record. Breeze Airlines expanded the number of flights it offered, and business reached nearly 5 million passengers in 2024 to set another record. In 2015, the airport had 18 non-stop destinations. In 2024, it had 45 non-stop destinations; flights connected Norfolk directly to Puerto Rico and San Diego.

Of the arriving passengers, 59% visited Virginia Beach at some time after flying into Norfolk. Military-related travel was the basis for 26% of the trips.

In response, airport officials announced a $700 million expansion plan in 2024. The growth included three more gates at Concourse A, a 168-room Courtyard by Marriott hotel, a new rental car facility, and new space for Customs and Border Protection as the number of flights to the Caribbean area increased. "Transform ORF" expanded into a $1 billion initiative by 2025.

As passenger counts neared 5 million, the Executive Director of the Norfolk Airport Authority commented:11

In 2025, Norfolk International Airport (ORF) succeeded in recruiting Jet Blue, with flights starting to Boston. It became the 9th carrier offering commercial passenger service at Norfolk. The airport's Chief Executive Officer said:12

The crosswind runway, constructed originally in 1943 during World War II, was closed to general aviation traffic and closed down completely in 2025. An airport official explained the timing:13

Norfolk International Airport (ORF) has one main runway and a parallel taxiway; the perpendicular and shorter crosswind runway was closed to commercial traffic in 2016 and completely closed in 2025

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Little Creek 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)