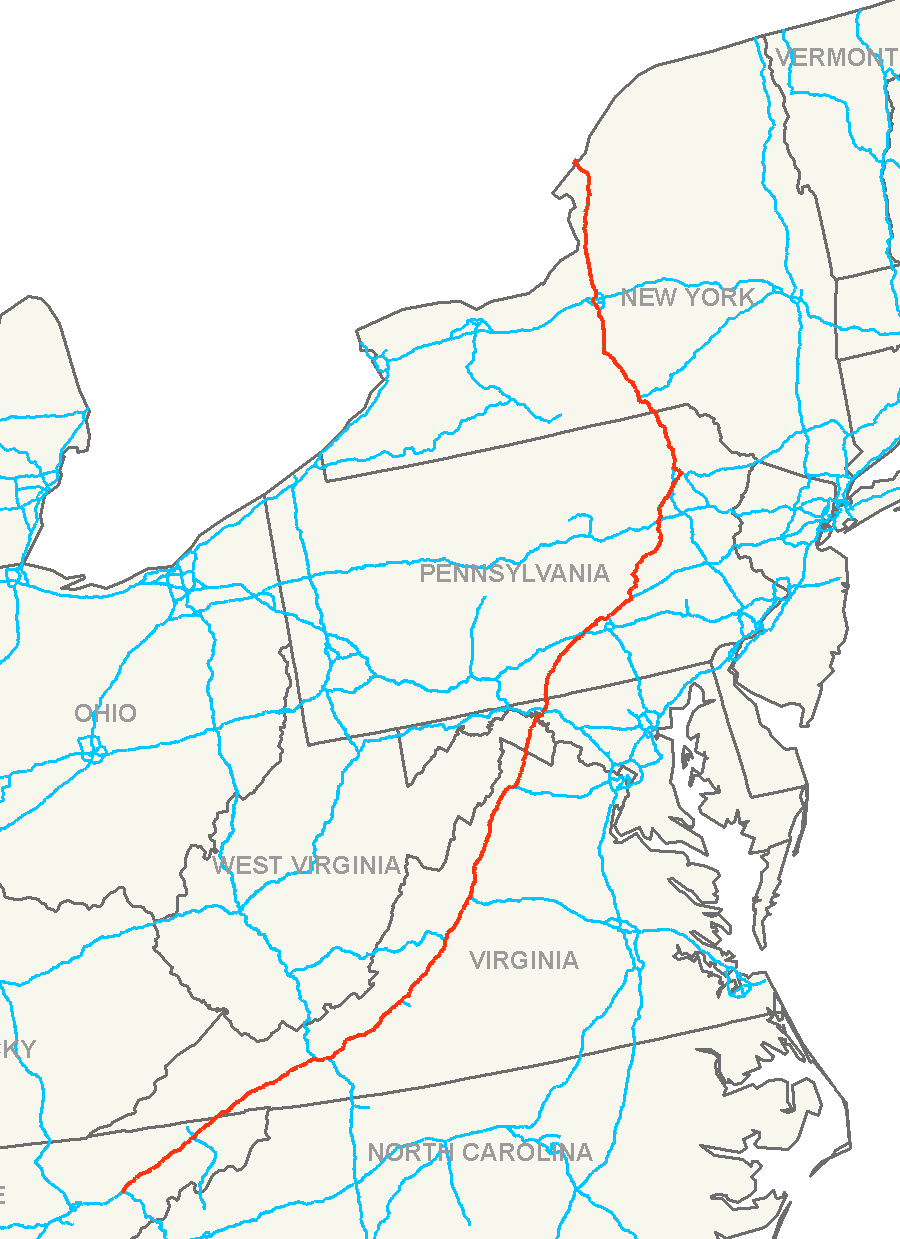

I-81 stretches from near Knoxville, Tennessee to the Canadian border

Source: Wikipedia, Interstate 81

I-81 stretches from near Knoxville, Tennessee to the Canadian border

Source: Wikipedia, Interstate 81

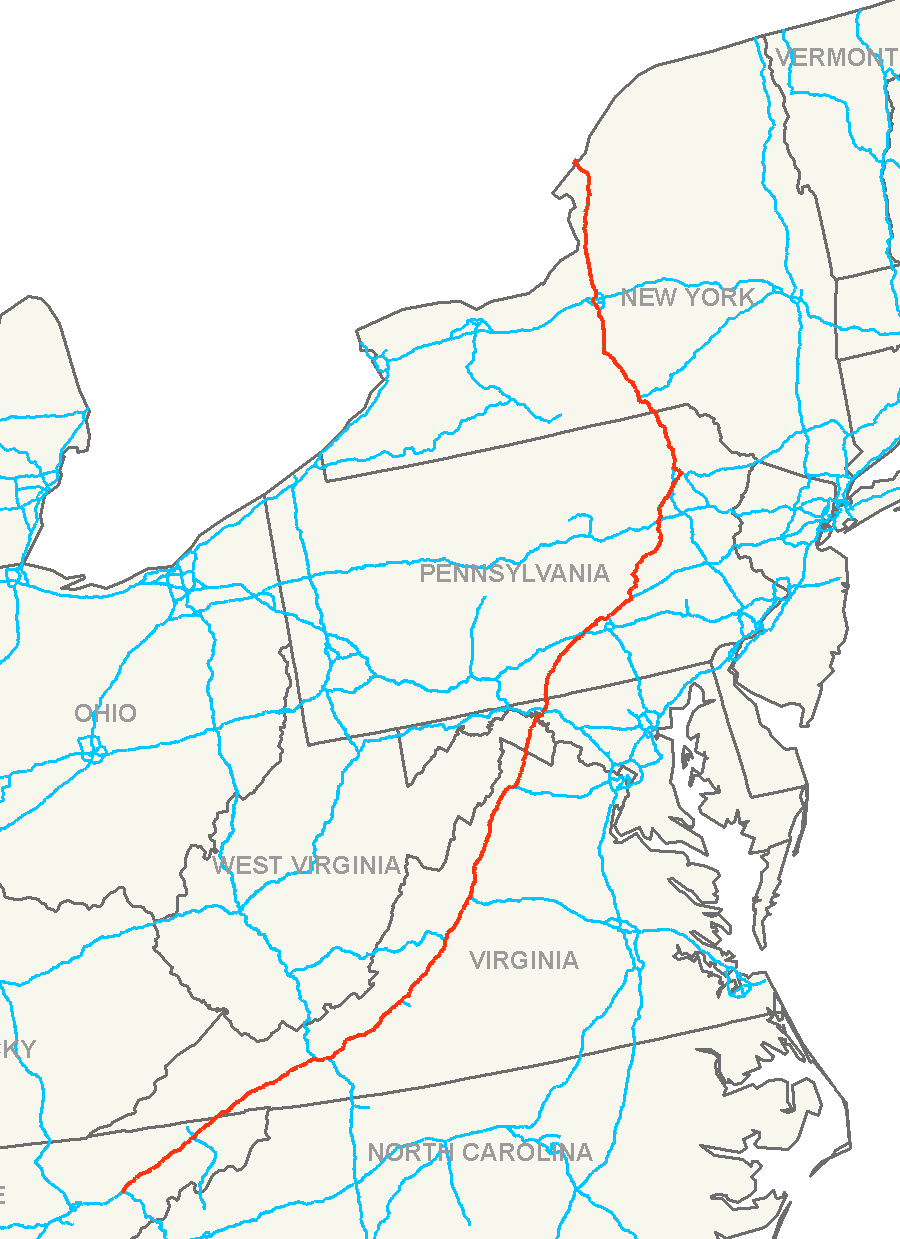

Interstate 81 stretches for 325 miles between the Tennessee and West Virginia borders, parallel to I-11. The route of the primary north-south road west of the Blue Ridge is actually northeast-southwest. The northern end of the highway in Virginia is 200 miles east of the southern end.

I-81 elevation at the Tennessee border is higher than at the Maryland border

Source: Commonwealth Transportation Board, Interstate 81 Corridor Improvement Plan (Figure 3)

The interstate exits are numbered starting at the southern end; Exit 323 is just south of the West Virginia border. I-77 and I-81 overlap for almost nine miles east of Wytheville. I-64 and I-84 overlap for over 30 miles between Staunton and Lexington.

I-81 was built between 1957 and 1971 as a four-lane highway. It has been widened to six lanes from the Tennessee border to Exit 7 near Bristol and where I-77 and I-81 overlap. In addition, truck climbing lanes have been completed near Christiansburg and Fairfield.1

I-81 is a four-lane highway through almost all of Virginia

Source: Commonwealth Transportation Board, Interstate 81 Corridor Improvement Plan (p.14)

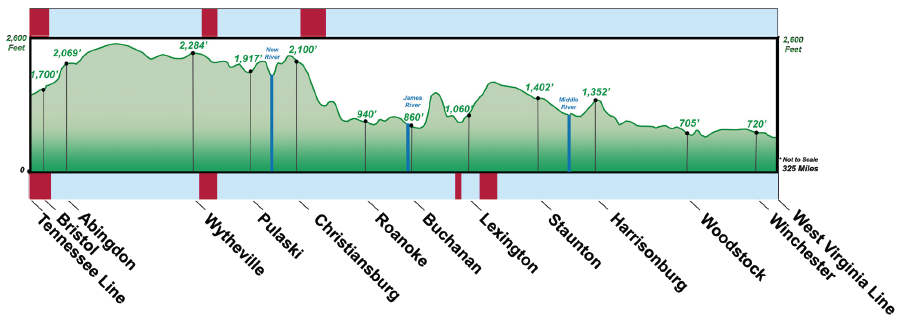

Travel is unreliable because of incidents, which cause 50% of delays. That percentage contrasts with other interstates in Virginia, where recurring delays during rush hour can be anticipated and incidents cause just 16% of delays.

Engineers assumed only 15% of the traffic on I-81 would be trucks, but by 2000 they composed 40% of the traffic. In 2007, the state completed origin-destination surveys at the two truck weighing stations on I-81 at Troutville and Stephens City, and determined that 62% of the trucks were passing through Virginia rather than picking up or delivering a load within the state.

In 2019, truck traffic was growing faster than passenger car traffic. The percentage of accidents related to heavy trucks (26%) was the highest of any Virginia interstate, and about 45 times each year incidents created four-hour delays on the highway. Experienced drivers, including those going back and forth from colleges along the interstate, knew to make a rest stop before a gas tank was less than half-full or anyone's bladder was more than half-full.2

unanticipated incidents cause most delays on I-81, in contrast to other interstates where rush hour congestion can be anticipated

Source: Commonwealth Transportation Board, Interstate 81 Corridor Improvement Plan (Figure 2)

In 1997, the Virginia Department of Transportation proposed widening I-81 to six lanes, except for 75 miles which would be expanded to eight lanes. The price tag was over $3 billion, and the proposal was not funded by the General Assembly. Instead, it ordered studies on intermodal transportation options to study the potential to divert traffic off I-81 and onto the Norfolk Southern railroad line that runs on the east side of the Blue Ridge before crossing into the Shenandoah Valley at Front Royal.

Those studies calculated that only 1-2% of passenger traffic could be diverted, but 10% of freight might shift to rail. Norfolk Southern estimated that it would have to spend over $1 billion to increase capacity in order to carry the extra freight.3

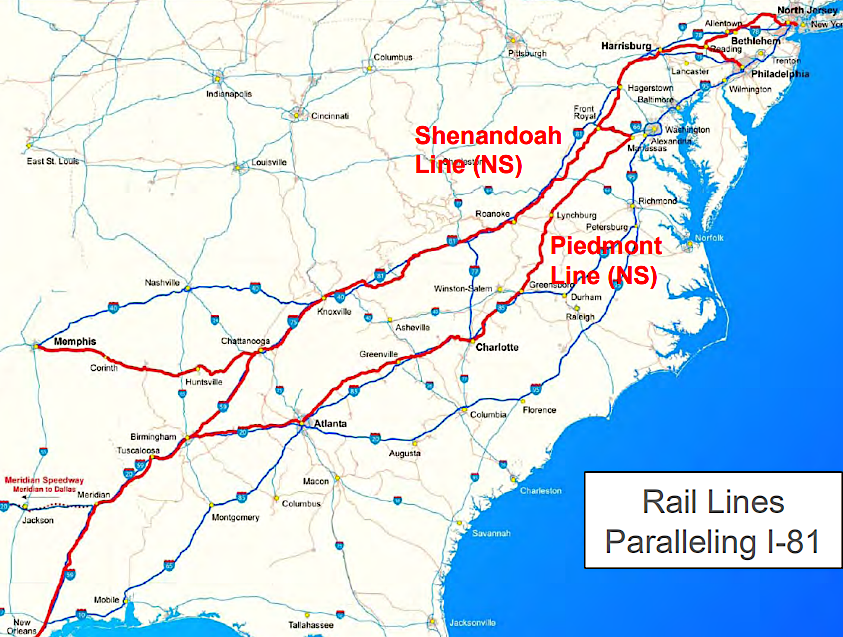

rail lines on either side of the Blue Ridge could capture some freight traffic, reducing trucks on I-81

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Feasibility Plan for Maximum Truck to Rail Diversion in Virginia's I-81 Corridor (Figure 19)

In 2002, the General Assembly created special transportation districts for Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads and planned for extra taxes to fund transportation projects. The conservative legislators from the western part of the state were less willing to increase taxes, so no special district or funding mechanism was provided for upgrading I-81.

Seeing an opportunity, a consortium of private companies known as STAR Solutions submitted a proposal based on Virginia's Public-Private Transportation Act of 1995. The companies would build two new truck-only lanes and widen I-81's regular lanes in urban areas to improve safety and reduce congestion. Tolls on the truck-only lanes would fund the costs and make the project profitable for the consortium.

The Virginia Department of Transportation then invited other companies to submit proposals, and required that they consider a multi-modal solution including railroad freight diversion. Two companies submitted bids in 2003. The proposal from a consortium known as Fluor Virginia proposed to add two car-only lanes in the interstate median, at an estimated cost of $1.8 billion. The other proposal from STAR Solutions proposed to rebuild I-81 into an eight-lane highway, with four lanes dedicated to truck traffic, at an estimated cost of $6-$7 billion.

Star Solutions proposed adding two lanes in each direction, dedicated to just truck traffic

Source: STAR Solutions, Phase Three Detailed Proposal - Improvements to I-81 Corridor

Virginia chose to partner with the STAR Solutions consortium, but the Federal Highway Administration required the Virginia Department of Transportation to complete an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) before signing a contract to build anything. The draft study, completed in 2005, examined over 200 different ways to expand road and rail capacity to reduce congestion on I-81. Proposals included widening the existing road, building separate lanes, and various combinations of wider/separate lanes to expand capacity between separate interchanges. Drivers seeking to avoid a toll on I-81 were expected to increase traffic on local roads, especially Route 11, but the highway engineers calculated that in most spots the existing local roads would not become excessively crowded.4

The final version of the Environmental Impact Statement was released in 2007. Before the state finalized a contract to proceed, the STAR Solutions consortium split apart. Negotiations for the public-private partnership ceased, and the 2008 recession constrained funding. The need to improve safety and reduce congestion continued, however.5

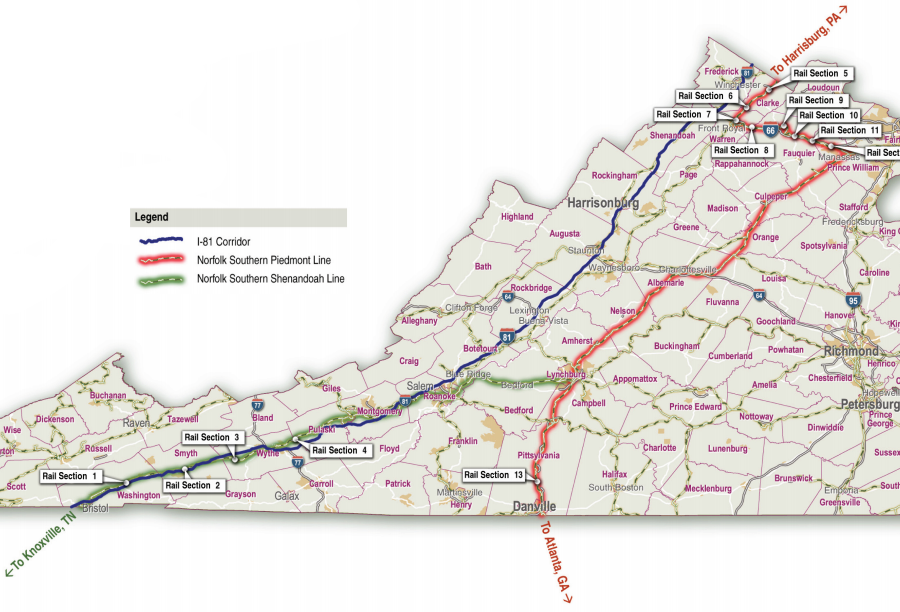

A 2010 study examined use of conventional intermodal transfer technology and also "open technology" that rolls truck bodies onto and off of railcars, allowing transport of gasoline tankers. Improvements were proposed to both the Shenandoah Line west of the Blue Ridge and the Piedmont Line east of the mountains, and full implementation would go beyond plans of Norfolk Southern to upgrade its Crescent Corridor. That 2010 study was more comprehensive, and explored increasing capacity between Knoxville, Tennessee and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in order to intercept traffic moving more than 500 miles.

The 2010 study concluded that full implementation of five different strategies could divert nearly 40% of truck traffic off I-81. Traffic going southeast-northwest, such as from Hampton Roads to Chicago or from Charlotte to Columbus, would not be intercepted, but long-haul and even short-haul freight headed southwest-northeast could shift to rail. The two major concerns of shippers were prince and on-time performance. Trucks were more reliable for on-time performance, but slow (30 miles per hour) trains could capture business because of their lower costs.

Implementing all five strategies could be done in sequence, and would cost $9 billion in Virginia and over $13 billion in other states for improving rail infrastructure and intermodal rail terminals. The most feasible option was to implement just the first strategy, to spend about $500 million to upgrade the Crescent Corridor capacity to handle more conventional long-haul intermodal traffic at traditional railroad speeds. That could divert more than 10% of the targeted truck traffic on I-81, a minimum of 1,255 trucks per day.6

the 2005 Tier I Environmental Impact Statement considered upgrading the Shenandoah rail line between Lynchburg-Bristol

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, I-81 Corridor Improvement Study: Tier 1 Final Environmental Impact Statement (Figure ES-1)

In 2018, the General Assembly directed the Commonwealth Transportation Board to develop an Interstate 81 Corridor Improvement Plan with proposals to fund implementation. By the end of the year, the Commonwealth Transportation Board approved the plan with $2.2 billion in priority improvements along the 325 miles of I-81 in Virginia.

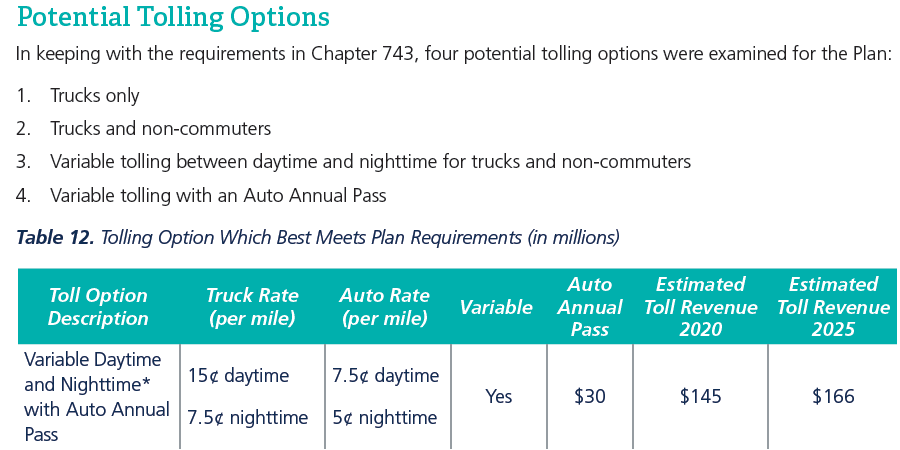

At the start of the 2019 General Assembly session, Governor Northam and key legislators announced a plan to use toll revenue, paid primarily by trucks, to fund the projects. Six toll gantries would be located 50 miles from each other on I-81 to collect tolls electronically.

Heavy trucks could end up paying over $55 each time they drove the entire length of I-81. The toll proposal included creating a $30 pass that would authorize unlimited use by cars for a year.

plans to add tolls to I-81 included heavier tolls on trucks and lighter tolls on cars

Source: Commonwealth Transportation Board, Interstate 81 Corridor Improvement Plan (p.36)

The Virginia Trucking Association argued that tolls were an inefficient way to collect revenue, and claimed trucks would bypass toll gantries by using parallel roads such as US 11. Residents living near I-81 objected to converting the freeway into a toll road, and the potential increase in local traffic from vehicles avoiding the six toll gantries. Northern Virginia legislators objected to the annual $30 pass for unlimited use, since residents in their districts were paying tolls every day for use of I-95, I-495, I-66, Dulles Toll Road, and the Dulles Greenway.

truckers successfully lobbied the General Assembly to fund I-81 improvements with tax and fee increases rather than tolls

Source: Alliance for Toll Free Interstates, Keep Tolls Off I-81

In the next session in 2019, the legislators could not agree on using tolls to provide the funding. The solution appeared in April, 2019. Governor Northam amended a bill to conduct another study and proposed to raise taxes instead of rely upon toll revenue, and the General Assembly quickly endorsed the revision. The trucking industry supported statewide increases in truck registration fees, a state surcharge on the road tax paid by trucking companies under the International Fuel Tax Agreement, and an increase in diesel fuel taxes.

The localities along the I-81 in Planning Districts 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 will collect a regional 2.1% fuels tax. The gasoline tax will raise about $150 million annually, and that revenue can be used to finance bonds and raise a large sum of money quickly. Unlike the transportation districts created for Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads, there was no increase in the sales tax to raise more funding dedicated to transportation.

A benchmark base price was defined for the fuel taxes, to ensure revenue would not drop below a defined threshold. February 2013 prices were set as the minimum for applying the taxes. Not coincidentally, prices had dropped about $1/gallon since then. Without setting that 2013 benchmark, Virginia would have collected significantly lower tax revenue based on 2019 prices.

to fund I-81 improvements, gasoline taxes were raised in the five planning districts (PDC 3-7) through which I-81 passed

Source: Commonwealth Transportation Board, Interstate 81 Corridor Improvement Plan (Figure 15)

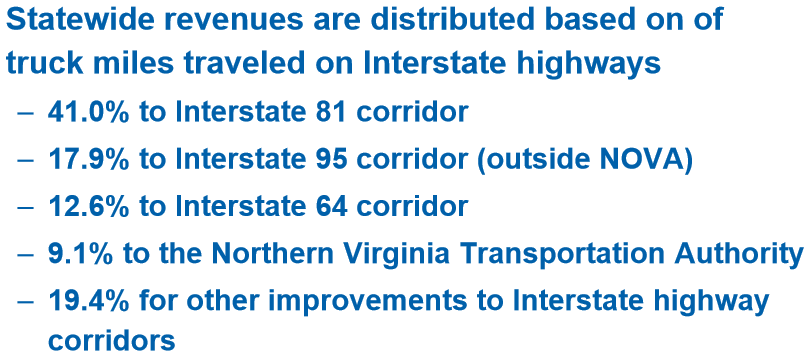

Part of the legislation included statewide increases in registration fees and road use taxes on commercial trucks, and diesel fuel taxes. Those increases provided new funding for not just I-81, but also for I-95/I-395/I-495 and I-66/I-264/I-664.

The increases were projected to generate $150 million annually for the Interstate 81 Corridor Improvement Fund. The revenue generated by the increase in statewide fees and diesel taxes is distributed based on truck miles traveled on interstate highways, so there will be $40 million annually in new funds for I-95, $28 million for I-64, $20 million for the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority, and over $40 million for other interstate projects.7

To negotiate regional priorities and allocate the funding for I-81 projects, the General Assembly created the Interstate 81 Committee. The 15 elected officials on it will determine the hottest of hotspots, and ensure that each part of the corridor regularly gets some benefits from the extra taxes.8

the 2019 legislation to generate revenue for I-81 also provided new transportation funding for other regions, facilitating passage in the General Assembly

Source: Commonwealth Transportation Board, Interstate 81 Corridor Improvement Fund and Program (April 9, 2019 presentation)

I-81 has the highest percentage of truck traffic of any interstate highway in Virginia

Source: Commonwealth Transportation Board, Interstate 81 Corridor Improvement Plan (p.7)