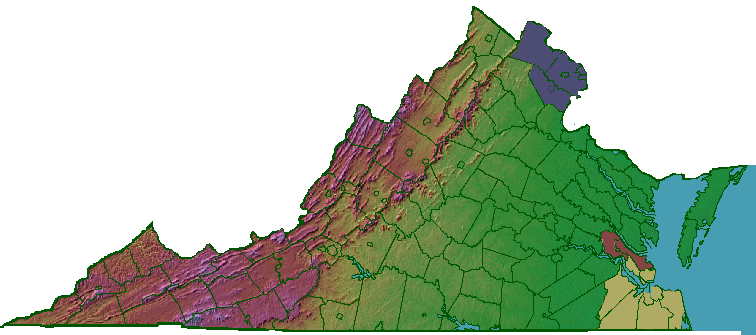

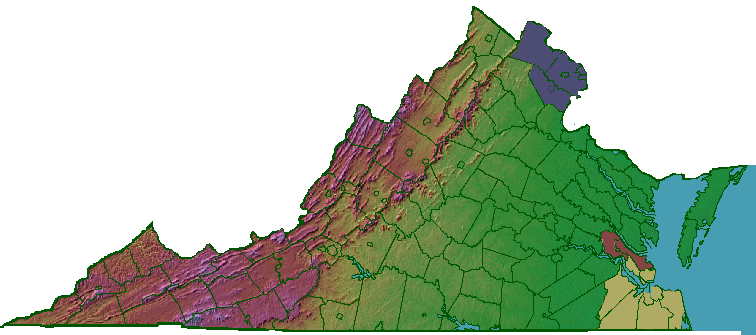

Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads have a 6% sales tax rate, except the city of Williamsburg and James City and York counties have a 7% rate

Source: Map Source: Ray Sterner, Color Landform Atlas of the United States

Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads have a 6% sales tax rate, except the city of Williamsburg and James City and York counties have a 7% rate

Source: Map Source: Ray Sterner, Color Landform Atlas of the United States

All Virginia jurisdiction charge at least a 5.3 % state sales tax. There is a 4.3% statewide sales tax, but all counties and cities have chosen to add the authorized maximium of an additional 1% local tax. The counties of Alleghany, Cumberland, Frederick, Pittsylvania and Powhatan were the last to add the local 1% tax.

Food for home consumption is taxed at a lower rate, with a standard 2.5% sales tax applied statewide.

The lower tax rate on "food for home consumption" does not apply to prepared hot foods sold for immediate consumption on and off the premises, so fast food restaurants must pay the full tax rate. A frozen pizza purchased at a store for heating at home is taxed at the 2.5% rate, but the full sales tax rate is imposed on a hot slice of pizza sold at the same store's deli counter.

The type of store where food is sold is irrelevant to the tax rate charged. The full sales tax or the reduced food tax rate applies whether the food is sold at a convenience store such as a 7-11, or at a full-service grocery store:1

The first statewide sales tax was approved by the General Assembly in 1966. By that time, 15 cities had already approved a local sales tax to fund government operations. The state legislature finally approved a statewide sales tax, after considering it for 20 years, in part to raise new revenue and in part to standardize how businesses would have to calculate and pay the tax. The state collects the local share and transfers revenue to the localities, eliminating the potential for local commissioners of revenue to create inconsistent procedures.

Passage of the sales tax reflected the political impact of redistricting, after the Supreme Court ruled in Reynolds v. Sims (1964) that election districts for both houses of state legislatures must be apportioned on a population basis. More legislators representing urban/suburban districts were supportive of a sales tax to finance expanded educational opportunities. With extra revenue, the state could provide a better education for whites and blacks after the Supreme Court had rejected Virginia's efforts to maintain "separate-but-equal" school systems, and also start a community college system.2

The 1966 Virginia Retail Sales and Use Tax Act set the initial state tax rate at 2%, rising to 3% in 1968. Localities were authorized to add an additional 1%. The tax applied to sale of tangible personal property and transient room rentals, but not other services. The sales tax did not apply to entertainment, but it did not affect any separate amusement taxes imposed by various localities on movie tickets, theme parks, etc.3

In 1986, the General Assembly increased the sales tax by 0.5% as part of Governor Balile's initiative to fund transportation. The legislature raised the sales tax another 0.5% in 2004 when Mark Warner was governor, dedicating half of the increase to education. Those increases raised the total sales tax rate to 5% statewide, with localities getting 1% of the total.4

The 2004 statewide increase occurred after an effort to raise the sales tax in two regions had failed.

Governor Warner and key elected officials in both parties supported a referendum in November, 2002, to increase the sales tax in Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads in order to fund more transportation projects. Opposition included those who opposed taxes in general. Smart growth also generated grass roots opposition. They were opposed to funding more roads without reforming Virginia's approach to transportation, and linking it to cost-effectiveness and making the connection between land use and transit-oriented development.

The votes were not close. In Northern Virginia, the referendum got only 45% of the vote. In Hampton Roads, only 39% supported raising the sales tax for transportation.5

The General Assembly had created the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority in 2002, but it was left with no funding after the voters rejected the referendum to increase regional taxes. In 2007, state legislators tried to authorize regional tax increases without a public vote. They empowered Northern Virginia Transportation Authority to raise seven regional taxes and fees, including the local sales tax on vehicle repairs, to fund regional transportation projects.

The Northern Virginia Transportation Authority (NVTA) planned to issue $130 million in bonds, to be repaid by the additinal taxes and fees. That was blocked after the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that the legislature had made a:6

In 2013, the General Assembly increased the sales tax by 0.7 percent in those regions to fund projects approved by the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority and the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission.

At the time, Governor McDonnell was a Republican, and that party also controlled the House of Delegates and the State Senate. The legislators agreed in a bi-partisan vote to raise taxes and direct the funding to regional transportation projects. The last major tax increase for transportation had occurred in 1986, when Governor Baliles was governor. At that time, the governor was a Democrat and both houses of the legislature were dominated by the Democratic Party.

One observer noted the significance of having the Republicans support tax increases:7

In 2018, the General Assembly also approved an additional 1% increase in the sales tax for James City County, Williamsburg and York County. Half was dedicated to promote the tourism opportunities in the Historic Triangle, and half was distributed to the three jurisdictions for local use. As part of the new tax, the General Assembly required Williamsburg to cancel planned inceases in hotel, meals and admissions taxes, and for all three jurisdictions to repeal a $2 hotel tax dedicated to tourism marketing.8

Those three jurisdictions were already within the area where the extra 0.7% sales tax applied to fund the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission projects. The 1% sales tax increase resulted in an overall 7% sales tax. That was the highest in Virginia, though other jurisdictions imposed additional taxes on some items (particularly a meals tax).

In 2023, Virginia had several separate regions with tax levels exceeding the 5.3% base (4.3% state plus 1% locality share):9

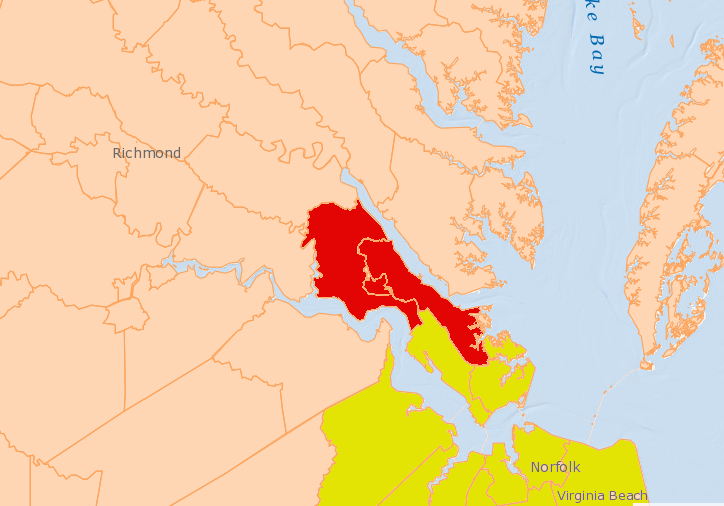

in 2018, three localities in Southeastern Virginia (red) had a 7% sales tax, while others had 6% (yellow) or 5.3% (tan)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The 1966 General Assembly passed the Virginia Motor Vehicle Sales and Use Tax Act, as well as the Virginia Retail Sales and Use Tax Act. The Motor Vehicle Sales and Use Tax, rather than the standard sales tax, applies to the sale of aircraft, watercraft, and motor vehicles.

The original tax level was 2%. Purchasers must pay today's 4.15% Motor Vehicle Sales and Use tax in order to get legal title to a vehicle. The value of the vehicle, and thus the total tax to be paid, is calculated on the gross sales price. That includes the dealer processing fee, but the gross sales price may be lowered by manufacturers' rebates and incentives. Dealers may accept a trade-in of another car as part of the sales process, lowering the total a customer must pay to the dealer, but the sales tax applies to the gross charge before any offset for a trade-in.

When private individuals buy/sell cars, the buyer must pay the sales tax in order to obtain title. Such deals could create an incentive to report a low sales price and pay a minimal tax, so the Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles sets the price based on the trade-in value in the NADA Official Used Car Guide.10

Virginia refers to a "use tax" as well as a "sales tax." The tax rate is the same. The distinction is based on whether a product or service is purchased within the boundaries of Virginia, or from a business with sufficient property or employess within the state to create a "nexus."

Virginia could not tax companies selling items by mail or through e-commerce channels, if the company had no offices, distribution centers, employees, etc. within Virginia. The US Supreme Court had ruled that individual states could not impose sales taxes on companies without a sufficient presence within that state's boundaries, and only Congress could tax interstate commerce.

In response, Virginia required customers within Virginia to pay the equivalent amount as a "use tax," to be filed with annual income tax forms. It was difficult to collect the use tax; few residents tracked the total of their purchases from Amazon or other e-retailers and then voluntarily paid the sales tax equivalent.

In 2018, the Supreme Court revised its previous decision, National Bellas Hess, Incorporated v. Department of Revenue of the State of Illinois in 1967 and Quill v. North Dakota in 1992. In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled in South Dakota v. Wayfair that Virginia and other states could require e-commerce and mail order retailers to collect the state's tax, for sales made by out-of-state businesses and shipped to customers within a state's boundaries.11

The Virginia sales tax has never been a Value Added Tax (VAT), and does not apply to wholesale transactions.