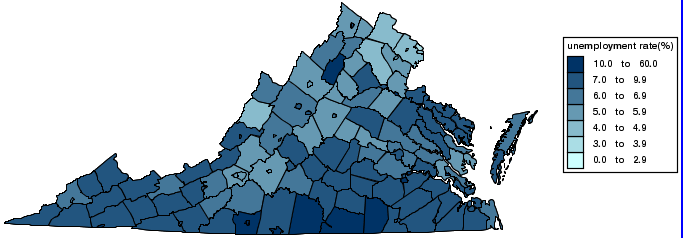

Unemployment rates in Virginia counties, February 2006 (not seasonally adjusted)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics

Wealth and poverty in Virginia are not distributed equally.

Northern Virginia is clearly the economic engine of the state economy now. Federal Government jobs provide a steady base of employment, and in the 1980's the Internet economy put Fairfax and Loudoun counties on the map as an international business location. Northern Virginia has high capacity to raise revenue, due to the relatively high salaries (the basis for income taxes sent to the state) and high property values (the basis for real and personal property taxes sent to local cities and counties).

Unemployment rates in Virginia counties, February 2006 (not seasonally adjusted)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics

Unemployment rates in Virginia counties, August 2011 (not seasonally adjusted)

while unemployment is higher statewide, the gap between Northern Virginia and the rest of the state remains...

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics

The wealthy jurisdictions in Northern Virginia provide the largest percentage of taxes for services provided across the state, but the majority of members in the General Assembly are elected from outside the Northern Virginia region. Not surprisingly, those politicians have created allocation formulas for state programs that transfer tax revenues generated from Northern Virginia to other regions in Virginia.

Since money raised in Northern Virginia is being redistributed to other regions in the state, Northern Virginia residents are not receiving enough revenue back from Richmond to finance all the desired services. To fund roads, schools, parks, and other services desired by local voters, Northern Virginia cities and counties are raising local taxes to meet needs that other regions expect the state to fund completely. No politician likes to raise taxes, so the pain of the extra taxes for local services is usually spread out over 20 years by selling bonds. Bonds require future taxpayers to cover most of the cost of long-term capital improvements, which those future taxpayers will use.

In contrast to Northern Virginia, the Eastern Shore is relatively poor. Accomack and Northampton counties were Virginia's first rural Enterprise Community, a designation that was followed by appropriation of over $20 million in Federal funds.

Not all portions of Northern Virginia are rich, of course. Even Fairfax County has pockets of poverty, especially along the Route 1 corridor, and Northampton has neighborhoods with fancy waterfront houses and golf courses. Bayview became known nationally in 1999 as the town without indoor plumbing, but not everyone there is on welfare.

The challenge today is to recognize where the rich and poor are located. Elected officials who need to raise revenue through taxes in order to provide services to voters need to identify the pockets of wealth, in order to extract funds from the rich and re-allocate those dollars according to priorities defined by the elected officials.

The basic concept of Virginia taxation, since the implementation of the graduated income tax almost 100 years ago, is that the government should take relatively more from the rich and give relatively more to the poor. Progressive taxation may seem to be "normal" today, but colonial and pre-Civil War Virginia operated on a different concept.

The "First Families of Virginia" steered tax dollars and allocated colonial resources - especially land - to benefit those who were already wealthy. Representation in the pre-Civil War General Assembly was unbalanced in the days before redistricting was based on the "one person - one vote" concept. Tidewater counties had more than their fair share of votes.

Prior to the Civil War, taxes on slave "property" (which was concentrated in counties east of the Blue Ridge) were minimized. That required taxes on other property (primarily land) to remain high. A substantial portion of those state taxes were committed to transportation projects funded by the Board of Public Works that were designed to benefit the residents of eastern Virginia. Residents of counties west of the Blue Ridge complained that the state was essentially taking from the poor to benefit the rich... and when the state of Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861, many of those western counties seceded from the state of Virginia and organized the new state of West Virginia.

Perhaps the greatest regional contrast in the revenue capabilities of Virginia counties is between Northern Virginia and the Appalachian Plateu counties in southwestern Virginia:

2004 revenue for four Northern Virginia counties

Source: Commission on Local Government - Local Revenue of Virginia's Counties and Cities, FY 2004

2004 revenue for three Appalachian Plateau counties

Source: Commission on Local Government - Local Revenue of Virginia's Counties and Cities, FY 2004

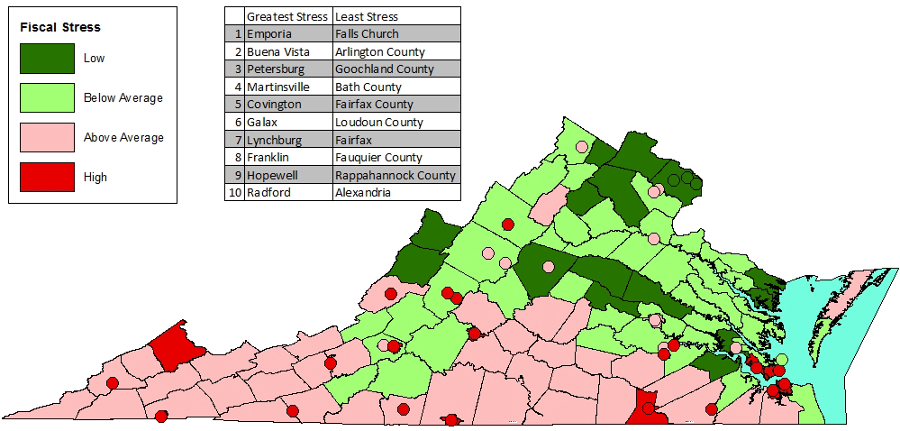

in 2014, incorporated cities were experiencing the greatest fiscal stress in Virginia

Source: Commission on Local Government, Part 1 - Overview and Fiscal Stress

The great disparity in property values and tax rates across the state results in a great disparity in the "revenue capacity." Some communities can afford to raise more money for public schools than other communities, because local K-12 schools (kindergarden through high school) are financed primarily by local property taxes.

Those communities with high property values and high tax rates can generate vast sums of money for the public school system, while communities with a less-robust economy struggle to provide basic facilities and to pay a living wage to teachers.

The result is a great inequity between the quality of a public education - Fairfax County has far more resources available for its school system than Brunswick County, for example. Should students in one part of the state be rewarded - or punished - by the local tax base? Virginia could reduce the inequity by shifting the primary school funding source from locally-based property taxes to state-based sales taxes...