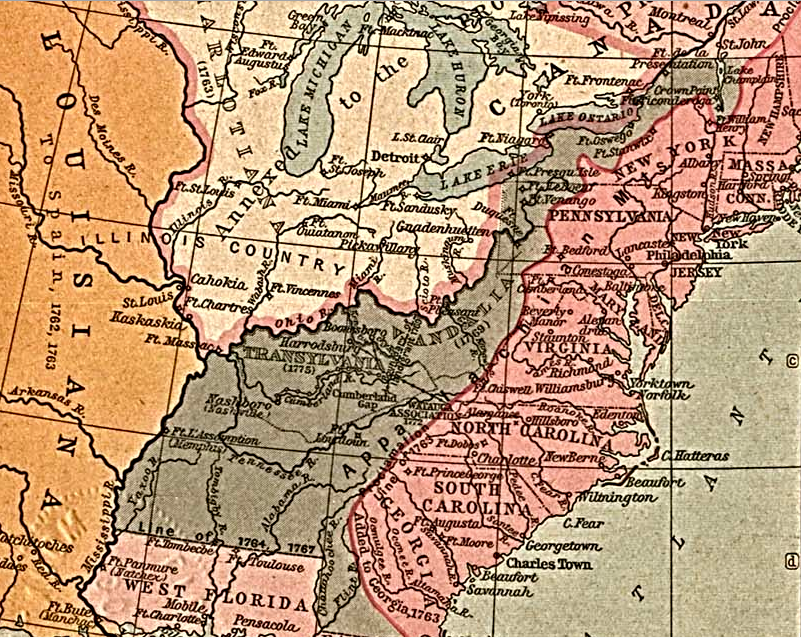

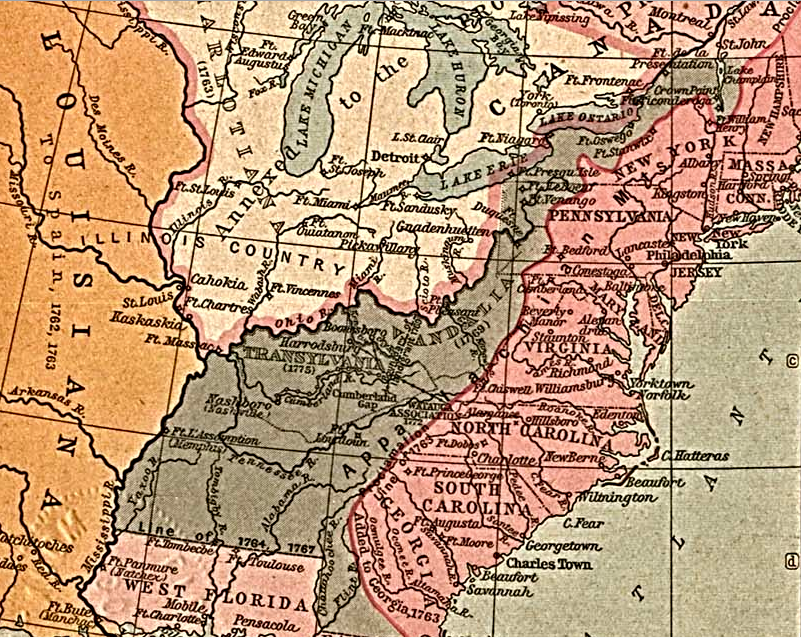

Transylvania

land speculators attempted to establish the Transylvania and Vandalia colonies in the territory acquired in 1763 at the end of the French and Indian War

Source: Library of Congress, The British Colonies in North America, 1763-1775 (from Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1911)

After the French and Indian War ended in 1763, American colonists anticipated they could settle western lands once claimed by the French. Wealthy investors with political influence who had already obtained land grants, particularly the Ohio Company and the Loyal Land Company, anticipated receiving revenue as parcels were sold. Other investors schemed to obtain new land grants.

The Proclamation of 1763 imposed a temporary barrier, officially barring the colonial governments from patenting parcels west of the Appalachians. The proclamation line was intended to minimize impacts of settlement on Native Americans, thus reducing the costs for the British military to maintain peace between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River.

The ban on settlement was severe. Those who had volunteered to serve in the provincial Virginia Regiment, including George Washington, were unable to survey and obtain official deeds to the land grants which had been promised in order to stimulate enlistments. Even those already living west of the Proclamation Line were supposed to leave. If enforced, that would require settlers in the Holston River to abandon their farms.1

The pressure to open western lands spurred John Stuart, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern District, to negotiate with the Cherokee in order to authorize a revision of the Proclamation Line. William Johnson, John Stuart, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern District, negotiated with the Iroquois to open up for settlement some of the land north of the Ohio River.

John Stuart

Encouraging Settlement and Land Grants West of the Blue Ridge

Exploring Land, Settling Frontiers

Virginia Places