timber rattler

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Digital Library

timber rattler

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Digital Library

Life may have formed on Earth 4.2 billion years ago, just 300 million years after the crust cooled enough to form solid rock. By determining an average rate of genetic change, biologists have established a "molecular clock" to estimate when species diverged from a last common ancestor. Tracing that molecular clock backwards produces an estimate that the original cells of life, a last common ancestor of all species which formed the equivalent of a modern prokaryote, had enough genetic material to produxce 2,600 proteins.

The first complex cellular organisms were probably thermophiles, heat-loving microbes in the ocean that fed on hydrogen (H2) released at underwater vents near volcanoes. Charles Darwin once speculated that life started when molecules in a "warm little pond" first clustered together. However, intense radiation striking the surface of the Earth before development of a shielding atmosphere sterilized the land. It is more likely that life began in the ocean depths.

The first forms of live then evolved into bacteria and archaea. Continuing environmental changes have triggered further adaptations that lead continuously to new forms of life, in either gradual changes or in spurts of "punctuated evolution." Over time, 99% of all the species that have evolved have disappeared. They went extinct as they failed to adapt, or as they morphed into new species. Geologic time periods are marked by mass extinctions. The failure of the "fittest" to survive created vacant niches that were filled with new species.

Archea, bacteria, and algae floating in the ocean evolved into the Ediacaran fauna that thrived until around 530 million years ago. Many new forms then developed in the "Cambrian Explosion."

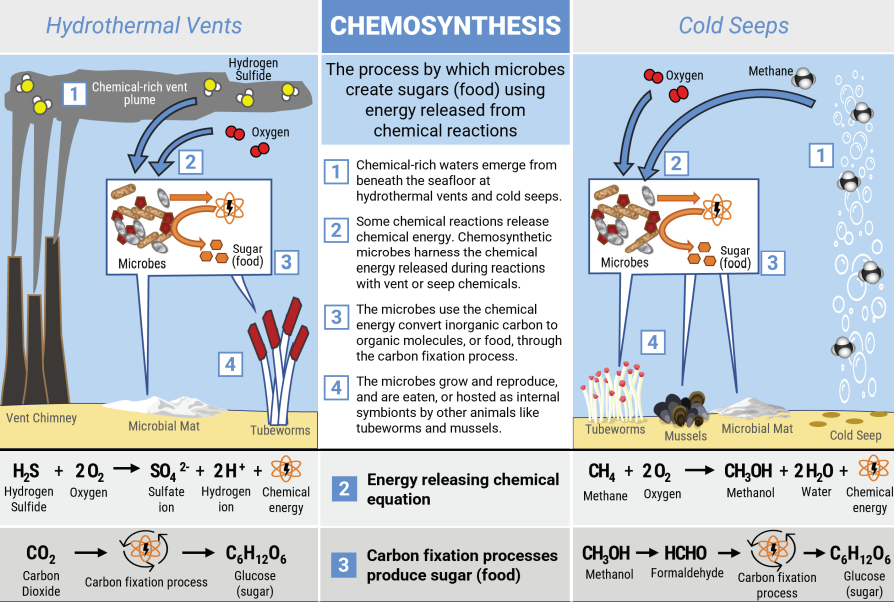

The existence of the chemosynthetic food web, not dependent upon photosynthesis based on sunlight, was first recognized in 1977 after archea and bacteria were discovered at hydrothermal vents on the ocean bottom. Current classifications of life include five kingdoms of Archea (Archeobacteria), Bacteria (Eubacteria), single-celled Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia. Archea and Eiubacteria may be lumped together into Monera.

Archea may be the closest form of life, still on Earth today, to the original cells that developed next to hydrothermnal vents. Today chemosynthetic communities thrive at the bottom of Norfolk Canyon east of Virginia Beach in cold seeps near methane vents. Chemosynthetic bacteria form mats on the ocean seafloor and live in a symbiotic relationship within tube worms and mussels.1

Virginia's most unique form of life may be chemosynthetic archea/bacteria still living at depth in bedrock or offshore next to methane vents on the Atlantic Ocean bottom

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Chemosynthesis

Classifying forms of life involves deciding where on the spectrum of evolution are those forms distinct enough to be species. Another common form of classification is to determine what are the "native" plants and animals in Virginia.

Natives are species that were living in Virginia before the arrival of Europeans who created the definition of "Virginia." Some native species are restricted in their range to just Virginia. It is most likely that these endemic to Virginia species actually evolved here in Virginia, separating from predecessor species to become genetically distinct.

There are five plant species that are endemic to Virginia, living within the state and nowhere else naturally. There are four endemic fish, three amphibians, and two mammals. The endemic mammals are the Smith Island Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus hitchensi) and the Pungo mouse (Peromyscus leucopus).

In addition, there are almost 160 endemic invertebrates, such as the Buffalo Mountain Mealybug (Puto kosztarabi), the Delicate Cave Beetle (Pseudanophthalmus delicatus), and the Madison Cave Amphipod (Stygobromus stegerorum).

The Plethodon genus of salamanders in the Blue Ridge have had 200-300 million years without glaciation to adapt to local drainages and microclimates. Since salamanders don't go for long walks, several species that evolved in Virginia's Blue Ridge have never crossed a state line on their own. Many have been carried back to out-of-state university labs in glass jars and plastic baggies by biologists, after collecting samples. The three endemic salamanders are Shenandoah Salamander (Plethodon shenandoah), Peaks of Otter Salamander (Plethodon hubrichti), and the Big Levels Salamander (Plethodon sherando).2

Species that have evolved to take advantage of unique characteristics in local situations are less flexible when circumstances change. "Generalist" species like Virginia pine may be at a slight disadvantage when competing with Table Mountain pine, but the "specialist" species are at a disadvantage when the circumstances change.

For example, the Fraser fir in the southern part of the Blue Ridge may have evolved from the Balsam fir. The Balsam fir is common up into Canada, but the Fraser fir is restricted to the Appalachian highlands. Perhaps the Fraser fir is better adapted to deal with the heat and drought in the southernmost part of the Balsam fir range. However, the Fraser fir is threatened by the wooly adelgid, a tiny insect that seems to be killing the Fraser fir forest on the top of Clingmans Dome in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Fraser fir on Mount Rogers and elsewhere are also threatened, and the species while the survival of the Balsam fir is not in question.

More specific to Virginia, the round leaf birch is a tree know to occur naturally at only one location, in Cressy Creek watershed near Chilhowee, Virginia. Other birch species occur throughout the area, especially "sweet birch," but along that one streamside a genetic mutation was favorable and a new species was better-adapted for that site. When the species was rediscovered in 1975, after being thought extinct, there were only 41 trees.3

not surprisingly, the shape of the round-leaved birch leaves are distinctive

Source: Wikipedia, Betula uber (by Jean-Pol Grandmont)

There is a very real possibility that the round leaf birch is naturally going extinct rather than just evolving into a new species. The round leaved species of birch may be poorly-adapted to current conditions. The one natural location could be the last remnant of a declining species, rather than the beginnings of the spread of a new species.

Extinction is natural. Botanists exploring the diversity of the "New World" collected seeds from the Franklinia atamaha tree in Georgia. The tree has never been seen in the wild since the 1700's, but the species survives in gardens across the world.

The current rate of extinction is unusually high due to human transformation of landscapes since the start of the Industrial Revolution. Ecologists are referring to the current time as the Anthropocene, reflecting the rapid rate of change in the natural settting as habitats and the climate are affected by the impacts of over eight billion humans now on Earth.

A species that is restricted in its range is usually at high risk of disappearing completely if circumstances change. The chain link fence surrounding the small plot of land on Cressy Creek does not even keep out vandals (maintenance of the fence is intermittent) and certainly would not stop what the lawyers call an "Act of God." One flood, one fire, and the round leaf birch could be eliminated from that one natural site in Virginia.

Like the Franklinia, the round leaf birch has been planted in other locations as a precautionary measure. Human vandalism, including illegal collecting for private gardens, was determined to be the greatest threat, and 15 years after discovery only 11 of the original 41 trees were still surviving.

The state and Federal governments provided seedlings from a nursery to reduce collection pressure on the natural population. Additional sites also reduced the risk that one disaster, such as a hurricane like Camille, could eliminate the species. In 2023 the US Fish and Wildlife Service started building a genetic library, "biobanking" the genetic information of species thought to be at risk of disappearing. Cryogenically preserving DNA was an insurance policy that would allow future study of genetic diversity and perhaps even restoration of a "lost" species.

The Virginia Round-leaf Birch Recovery Plan prime objective was to grow the existing population to a sustainable level of 10,000 trees. The goal was defined:4

Mechanics who take apart a piece of equipment are careful to save all the nuts, bolts, screws, and washers as well as the large and obviously-important pieces. As humans change the landscape of Virginia, the endangered species advocates want to save all the pieces of our natural systems, including more than the whales and elephants. Conservation involves tradeoffs; protecting critical habitat may raise the cost of building new houses, roads, power plants, docks in tidal creeks, etc.

The main law protecting rare plants and animals is the Federal Endangered Species Act. It is not popular in some places, and is known as the "shoot, shovel, and shut up" act in a few locations where the economic impact of conserving habitat is high.

Even though there is strong public support for saving charismatic megafauna like the bald eagle, officials still get reliable reports of secret, illegal destruction of eagle nests that might interfere with projects such as Cherry Hill on the Potomac River in Prince William County. It is much harder to convince developers, or the average taxpayer and voter, that the small pieces of the web of life are just as important as the national symbol.

The Shiny Pigtoe mussel (Fusconaia cor) in the upper Tennessee River watershed may have evolved to be slightly different from other mussels since the ice ages, but it does not appear to hold the key to curing cancer. Why should we spend so much time and effort saving it? The Lee County cave isopod is just an isopod, and from a utilitarian perspective... what has that species ever done for humans?

the Shiny Pigtoe mussel lives naturally only in the headwaters of the Tennessee River, and nowhere else in the world

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Fusconaia cor and Shiny Pigtoe (Fusconaia cor)

The decision to "delist" the bald eagle will allow more development of its natural habitat, such as the forested shorelines along the Potomac/Rappahannock/York/James rivers. The proposal was controversial - the current populations of bald eagles are healthy, but look for second homes to line the shorelines in 20 more years. If the population drops again, this time because of loss of habitat instead of DDT poisoning, the eagle might be relisted in the year 2020. Biologists have really long calendars, when they talk about extinction potential.

bald eagle with fish in talons

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Digital Library

Virginia identifies "rare" species in the state, in addition to those species officially listed as "threatened" or "endangered" by the Federal government. There's a standard set of codes for "rare" species. Code "S1" means they are rare in Virginia, while "S5" means they are common. G1 means a species is rare globally, and "G5" means it is common worldwide.

The state designation is of concern to Virginia agencies - but walk across the border into North Carolina and the classification might be different. So... if a species is at the edge of its normal range, rare in Fairfax County but common elsewhere - should we bother to protect it here?

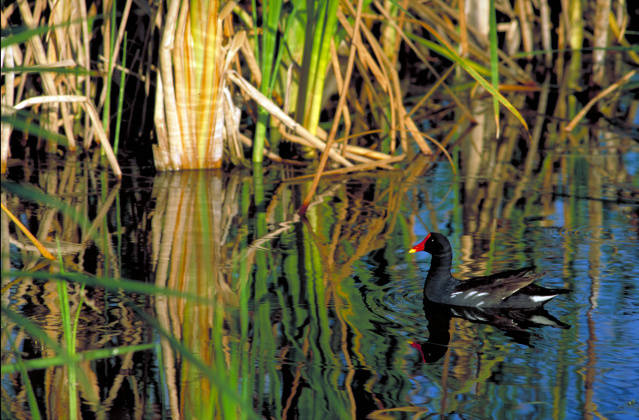

For example, the "Common Moorhen" (Gallinula chloropus) is S1/G5 - common elsewhere, but rare in Virginia. The bird is, well, inedible at best; it is also known as the "mudhen." Because it is rare in Virginia, does that mean policy makers should not propose a highway through its habitat in Virginia if the alternative is to route the highway through already-existing subdivisions and tear down occupied houses?5

species that are rare in Virginia, such as the Common Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus), may be common in other places and require no special protection

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Common Moorhen

In 2021, there were 71 species in Virginia listed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service as "threatened" or "endangered." The Federal agency proposed to remove 23 species nationwide in late 2021. On October 16, 2023, the Federal agency delisted 21 species and declared them to be "extinct." That ended the need to designate and protect critical habitat for those specis, but in some cases other species still on the threatened and endangered list required the same habitat to remain protected.

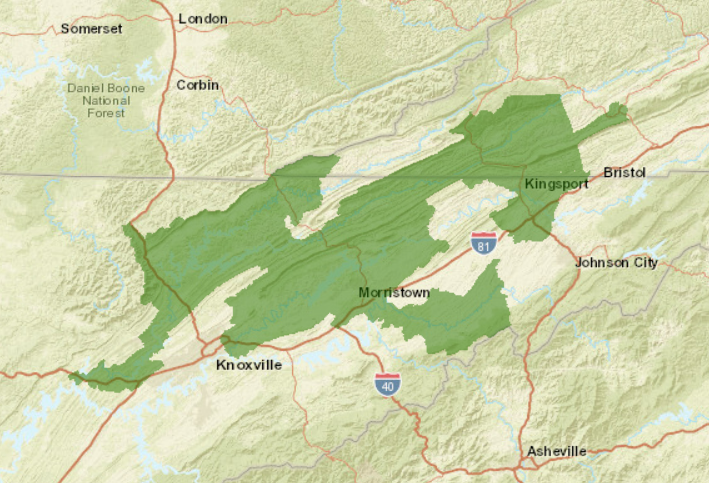

The green-blossom pearly freshwater mussel (Epioblasma torulosa gubernaculum), one of those 21 species reclassified as extinct, was formerly found in Virginia. Its shells were still present in the Clinch River in Southwest Virginia in 2023, but no live green-blossom pearly freshwater mussels had been spotted since 1984.6

former habitat of the green-blossom pearly freshwater mussel (Epioblasma torulosa gubernaculum)

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Environmental Conservation Online System (ECOS)

Delisting was justified because it was too late to achieve recovery under the Endangered Species Act (ESA):7

Also in 2021, Virginia banned keeping an Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) as a pet. The US Fish and Wildlife Service did not list the species as threatened, but some states have listed it as a species of special concern. The Virginia Herpetological Society is concerned about the loss of reproductive adults in isolated woodlots and forest fragments.

Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina)

An official in the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources commented that the ban did not limit enjoying turtles encountered in the wild:8

The presence of the endangered smooth coneflower (Echinacea laevigata) forced a re-routing of the planned "Smart Road" at Virginia Tech. The Virginia Department of Transportation had to identify alternatives to avoid impacting the population on the preferred route. The patches of smooth coneflower in Montgomery County were one of the 21 remaining populations, and 39 other known populations had disappeared.

The Smart Road, which could have become part of a new I-73, ended up as just a test track for automobile research. Efforts to recover the smooth coneflower succeeded in creating a total of 44 populations betwen Georgia and Virginia, and in 2022 the species was downlisted from "endangered" to "threatened."9

the endangered smooth coneflower (Echinacea laevigata) was a barrier to a proposal to extend the Smart Road to I-81 in 1994

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, A bumblebee foraging on a smooth coneflower

In 2024, the US Fish and wildlfe Service proposed delisting a small fish, the Roanoke logperch (Percina rex). That darter had been classified as "endangered" in 1989, when there were populations remainng in just 18 streams. Because there were Roanoke logperch found in 31 streams in Virginia and North Carolina, the Federal agency no longer considered the small fish to be even "threatened" wth extinction:10

the Roanoke logperch is now found in 31 streams, and the species is no longer thought to be at risk of extinction

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, USFWS National Digital Lbrary, Roanoke logperch

round-leafed birch

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Digital Library

the Franklinia tree went extinct naturally in the wild in the 1700's

Source: Wikipedia, Plate 59 from The North American Sylva: Franklinia alatamaha - Franklin tree