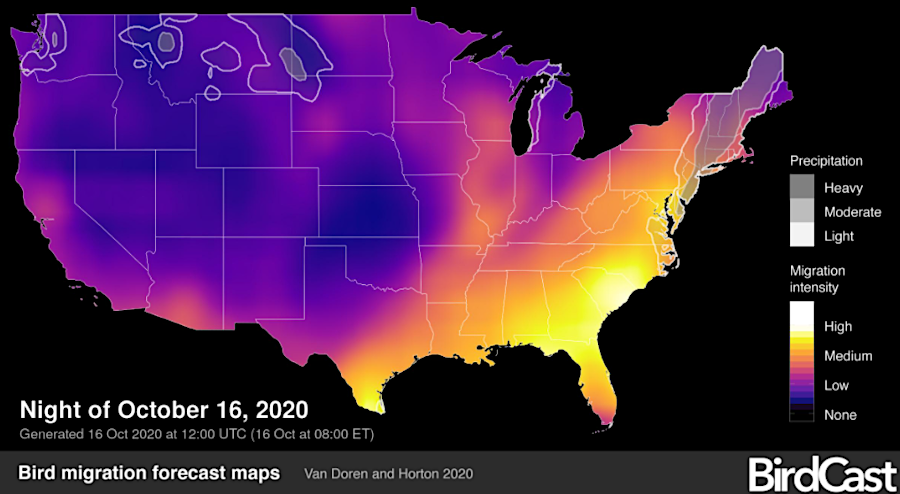

weather radar records now allow predictions of the intensity of bird migrations, as well as storms

Source: BirdCast, Bird migration forecast maps

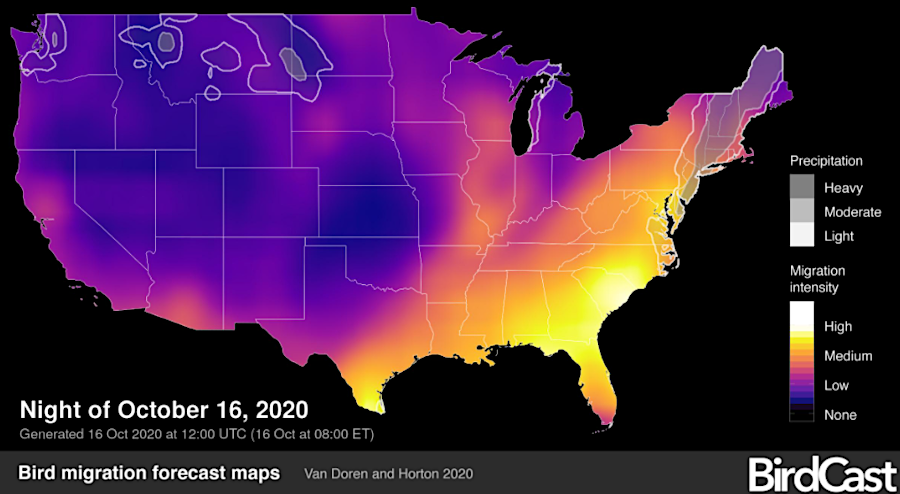

weather radar records now allow predictions of the intensity of bird migrations, as well as storms

Source: BirdCast, Bird migration forecast maps

What makes Virginia attractive to different species, at different times? There's a reason why the tourists go where they go, when they go, in Virginia. Just as different areas of Virginia attract different tourists during different seasons, the state offers a wide range of habitats for wildlife at different times of the year.

All birds do not fly into Virginia in the Spring and leave in the Fall - but that is pretty much what happens around Hudson Bay in Canada. When the weather gets tough, the tough get going... south, where there is food, unfrozen water, and warm sunshine.

Tourists flock to places like Williamsburg in the summer because school is out of session and families can vacation together. Those who "hit the beach" in the summer are driven in part by the seasons; body surfing the waves or cruising the boardwalk in a bikini makes sense only between May and September. Leaf-lookers crowding the highways to Shenandoah National Park in October are getting a peek at the peak Fall colors.

Virginia also hosts northern populations of songbirds who flew down from northeastern states. Robins overwinter in Virginia, feeding on fruits and berries because the soil is frozen further north. In the spring, as the average temperature reaches 37°F, robins move north to feed on earthworms in places such as Connecticut.1

The birds are as selective as a family with teenagers choosing where to vacation for a week. Some habitats that attract birds are natural, but others are man-made. Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge manages 14 ponds known as "moist soil management units," totaling 2,600 acres. By raising and lowering the water at different times of the year, the refuge biologists can attract the ducks, herons, geese, and other aquatic birds.2

Geese and other birds concentrate on the refuge each winter. The bird watchers are close behind. The birds depend upon the biologists to create a setting with food and shelter each year, and the businesses in the area depend upon eco-tourism in the winter. Want a duck carving? Go to Chincoteague, and choose from decoys carved by a wide array of skilled artists.

First there was the beach, then the birds, then the tourists, then the commercialism. The development at Chincoteague certainly did not occur in the reverse order; it was based on the beach and the birds.

In the case of the birds, there is a long history of natural selection. Birds evolved from dromaeosaurs, feathered dinosaurs related to velociraptors, about 160 million years ago. The asteroid that created the Chicxulub crater 66 million years ago caused all the bird-like dinosaurs with teeth to go extinct, along with almost all the other dinosaur species. The survivors were some species of bird-like dinosaurs with beaks/bills, without teeth. They could peck in the soil for nuts and other food sources that were not destroyed by the impact.3

What species fly where in Virginia, and when, is still shaped by natural selection.

Today, thousands of snow geese (Chen caerulescens) migrate each Fall to the marshes on the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic coastline. They show up from Assateague Island all the way south to Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge. In the Spring, they leave - because the Canadian wetlands offer more food and fewer predators on nest sites than the Virginia marshes.

In 2023, Hurricane Idalia in August apparently blew off course a flock of American flamingos flying between Yucatan Peninsula and Cuba. Two months later, two pink flamingos arrived at Chincoteague. Tourists were delighted to watch them feeding in the shallow waters on seeds, crustaceans, and aquatic invertebrates. That attracted a tourist surge of birders, and led to production of t-shirts saying "Chincoteague Flamingo Swim 2023."

even flamingos have been spotted at Chincoteague, after Hurricane Idalia blew them north in 2023

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Greater flamingo

Bird have specific habitat requirements. Ospreys feed on fish, so they are common in Westmoreland County and not in Buchanan County. Robins have specific requirements for where they nest. In the middle of the day, air temperature must be 45-65°F and relative humidity must be at least 50%. Under those conditions, the invertebrates upon which robins feed, including earthworms, will be present in the upper layers of soil.4

The blackpoll warbler (Setophaga striata) makes of the most remarkable migrations of a Virginia bird. In the Fall, the tiny (12 gram) birds will fly non-stop for up to 1,500 miles over three days to reach a Caribbean island, on their way to South America for the winter.5

The US Geological Survey estimates that over 4,000,000,000 birds migrate across North America annually. The Next Generation Weather Radar (NEXRAD) system can track them, and machine learning/artificial intelligence can separate the signals reflected by birds from nonavian clutter.

By 2023 computer models could predict migration events, which are associated with weather systems, as much as a week in advance. The data facilitates efforts to minimize harm from spinning wind turbines. It is also used by the Lights Out campaign to determine when to turn off lights that disrupt migration patterns and cause birds to fly into buildings.6

Source: Wildlife Center of Virginia, Untamed Unfiltered, Episode 10: Migration