male mallards ("drakes") have a distinctive green head

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Mallard drake

male mallards ("drakes") have a distinctive green head

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Mallard drake

Most ducks in Virginia migrate north in the Spring to breed, then return south in the Fall. They winter in Virginia, especially in wildlife refuges and management areas designated as important bird habitat by state and Federal agencies.

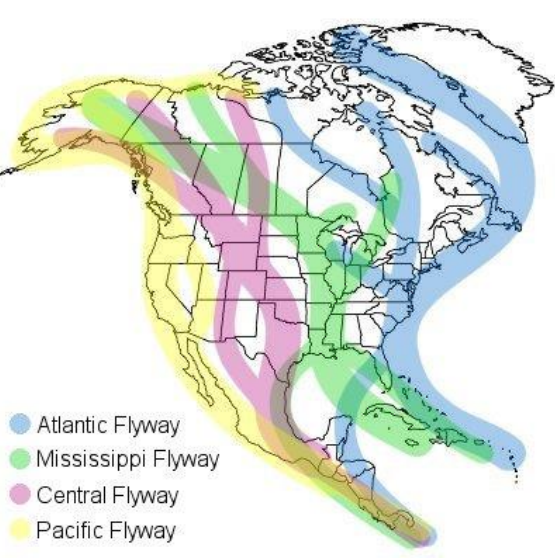

Hunters have been essential in acquiring that habitat and protecting the bird populations. The US Fish and Wildlife Service works with state wildlife management agencies, and the Migratory Bird Regulations Committee establishes regulations for annual harvest of different duck species. The regulations reflect the success of summertime breeding in different flyways, with hunters authorized different limits per species and hunting days reduced/expanded based on bird populations.1

Virginia is in the Atlantic Flyway

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Saving the Monarch Butterfly, One Yard at a Time

The population of mallards in the Atlantic Flyway expanded significantly in the 1900's, largely from habitat conversion in eastern Canada. Timber harvest opened up new territory for summertime breeding by mallards, and they became the most common duck species in the Atlantic Flyway by the 1960's.

Black duck populations declined after World War II. There were concerns that the species was being impacted by hybridization with mallards. A 2019 study by geneticists determined that 25% of black ducks had mallard genes, but the percentage was not increasing.

The hybrid ducks were more likely to interbreed with mallards rather than black ducks. In addition, over 90% of mallards east of the Mississippi River had Eurasian genes. Those were introduced when wild ducks bred with game-farm mallards that had been used to increase that species population in the 1900's. Black ducks were far less likely to breed with the game farm birds.

The DNA study results were a surprise:2