Virginia Big-eared Bats

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Digital Library

Virginia Big-eared Bats

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Digital Library

Of the 45 bat species living in the United States, 15 are normally present in Virginia (and two others have been recorded). They are all insect eaters, catching mosquitoes, moths, and other insects on the fly. Virginia has no nectar-feeding bats or vampire bats that feed on blood.

Bats evolved about 65 million years ago. Because they hunt using echolocation, a term invented in 1944, insects developed a new capability to hear ultrasonic frequencies in order to evade the flying predator. Bats somehow managed to develop a sonar system and a nervous system fast enough to "ping" an area, then adjust sound frequencies and timing in order to zoom in on flying insects. A single little brown bat can catch 600 mosquitoes in one hour.

Bats do not get cancer; research into their genetics may illuminate why. Some bat species have long telomeres that delay the effects of aging. Telomeres in humans are repaired by the enzyme telomerase, but cancer cells use that same enzyme in order to keep dividing and spreading throughout a human body. Bats repair telomeres without that enzyme, suggesting there may be a biochemical pathway to extend human longevity.1

In March, 2005, Governor Mark Warner signed a new state law designating an official state bat - the Virginia big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus, also considered as a subspecies of Townsend's big-eared bat Plecotus townsendii). In his signing statement, Governor Warner expressed a wry sense of humor that is not always evident in elected officials:2

sleeping in normal position - feet at top, head down

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service

About half of Virginia's bat species depend upon caves as sites for sleeping and raising their young. The other half rely upon trees, old logs, and other buildings for shelter. Three species - Big Brown Bat (Eptesicus fuscus fuscus), Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus lucifugus), Evening Bat (Nycticeius humeralis humeralis) - are likely to roost inside houses and trigger conflict with homeowners unwilling to share their space with flying mammals.3

Human disturbance in caves during the winter can force the bats to burn energy during their normal hibernation cycle. Just two disruptions of hibernation can cause bats to starve before insect populations re-appear in the Spring and provide a food source.4

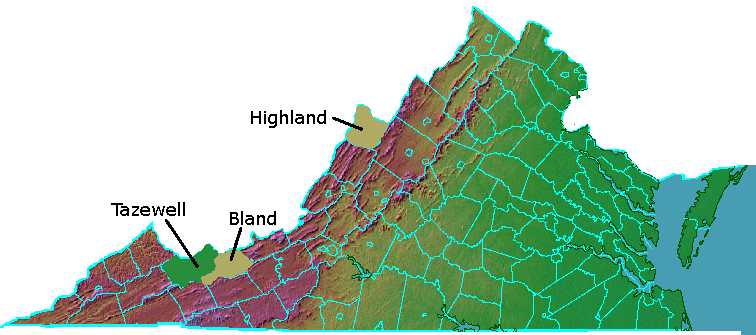

The Virginia Big-eared Bat spends winter and summer in the same territory. In the Spring, the females join together in maternity colonies to birth their bat "pups." While there are more Virginia Big-eared Bats in West Virginia than in Virginia, the state bat of Virginia does roost in three Tazewell County caves during the Summer (in contrast to most cave-dwelling species that hibernate in caves just during the winter). Individual bats may fly as much as six miles away from their roosting site to feed in the same area, night after night. In the Winter, the population disperses to roost in additional caves in Highland and Bland counties, as well as Tazewell County.5

Virginia Big-eared Bat Summer roosting territory

Other species of bats migrate seasonally like birds, but the winter/summer territories of bats are typically within 100 miles. (The hoary bat can migrate as much as 250 miles, and that species reached the Hawaii islands across 2,500 miles of water.) When cold weather approaches each Fall, deciduous trees drop their leaves and many ground-level plants die back. Without a food source, insects lay eggs or hide in various crevices to overwinter, leaving bats with no food source.

One solution for bats is to find a cold spot to hibernate, lowering body temperature to almost the temperature of the surrounding cave and suspending most metabolic processes to reduce the need for food. Hibernating bats seek out caves where temperatures are between freezing (32°F) and 49°F. South of Virginia, many caves are too warm for hibernation, and at least one population of gray bats migrated north out of Tennessee to overwinter in cooler caves.6

Source: Wildlife Center of Virginia, Bats Have an Important Role in Our Ecosystem, Such as Increasing Biodiversity in Our Environment

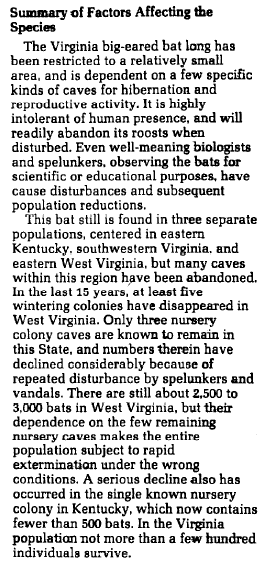

In 2021, three bat species in Virginia were listed as endangered: Gray Bat, Indiana Bat, and Virginia Big-eared Bat.7 The traditional threat to the survival of the species was human disturbance inside caves, forcing bats awake and causing them to exhaust food reserves. Bat hibernation should end when food supplies, typically insects, have returned in the Spring, so bats will starve to death if hibernation is interrupted and stored energy is used up before the insects return.

A new threat is collisions with wind energy turbine blades and tall telecommunication towers. The death of over 1,000 bats at Mountaineer Wind Energy Center (West Virginia) in 2003, followed by additional deaths in 2004, triggered research efforts to determine how to minimize bat/windmill collisions. The migration season in the fall appears to be the time of greatest risk.8

Federal Register Notice proposing

designation of

critical habitat for Virginia Big-eared Bat, in 1979

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service

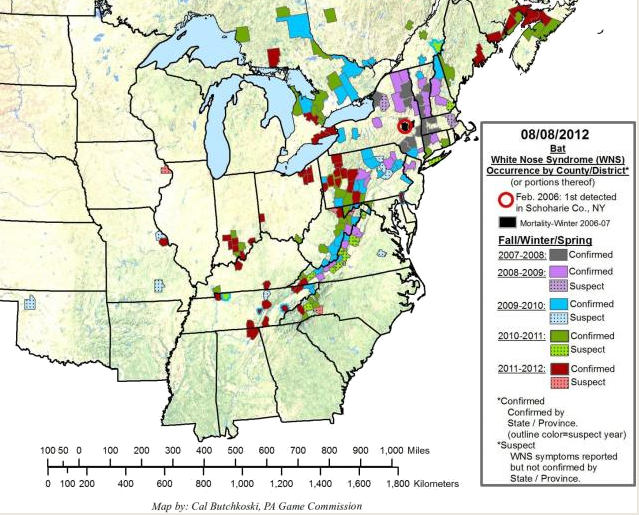

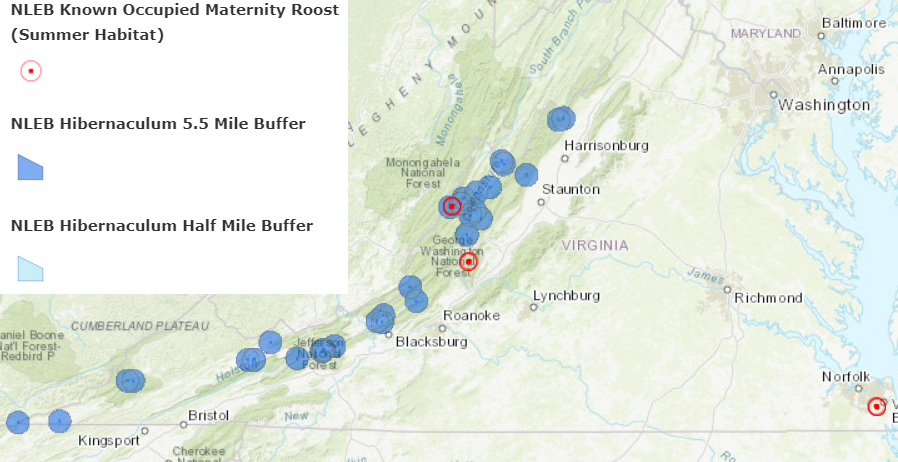

spread of white-nose syndrome, from New England into Virginia/Tennessee

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service

white-nose syndrome in 2011

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, White-nose syndrome map

expansion of white-nose syndrome in 2012

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, White-nose syndrome map

expansion of white-nose syndrome in 2013

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, White-nose syndrome map

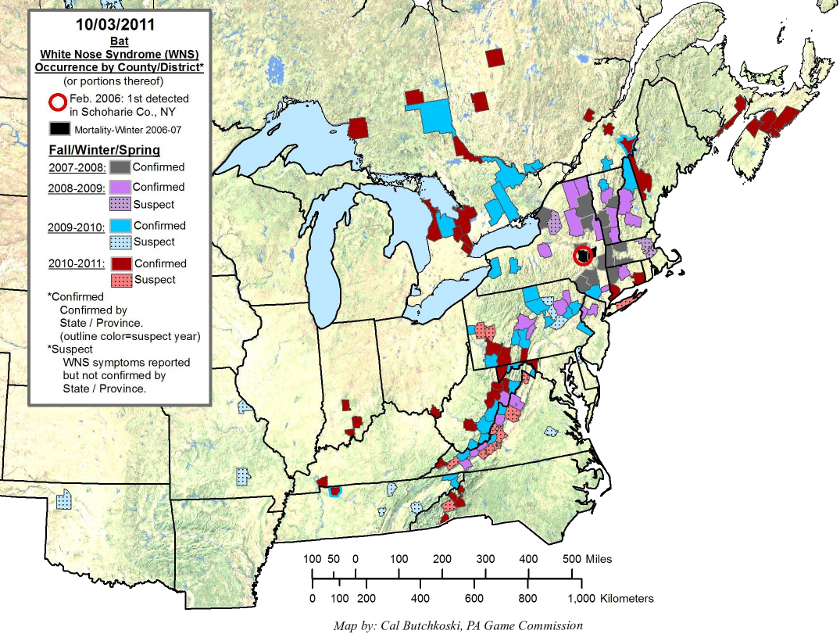

A disease known as white-nose syndrome, apparently caused by the Pseudogymnoascus destructans (formerly Geomyces destructans) fungus, threatens to eliminate some bat species in Virginia. Massive die-offs appeared first in New York/New England in 2006, and has since spread south. The first Virginia infection was identified in a Bath County cave in 2009.9

Under the assumption that white-nose syndrome was spread by cavers introducing the fungus into new locations, in 2009 the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries and the U.S. Forest Service closed all caves on state and Forest Service lands in Virginia to recreational caving. By 2012, it was clear that quarantine efforts had failed and the fungus causing white-nose syndrome could not been kept out of any Virginia caves.

The last watershed in Virginia to report the presence of white-nose syndrome was the Powell River. In February 2013, the disease was confirmed in Cumberland Gap National Historic Park. By 2022, it was present in 38 states and seven Canadian provinces:

There are 47 bat species in the United States, and over half hibernate in the winter. Those species are especially sensitive to white-nose syndrome, which triggers the immune systems and causes bats to burn up their stored energy before hibernation season has ended. By 2022, twelve of the cave-hibernating bat species had been infected.10

little brown bat affected by white-nose syndrome

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Digital Library

In late 2009, the National Zoo started to establish a colony of Virginia Big-eared Bats. Forty bats, not yet infected by the fungus, were captured and moved to the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute at Front Royal, Virginia. Only eight survived the winter, reflecting the challenge of creating an artificial environment that matched the requirements of the species. There appears to be no way to conserve the official state bat species in captivity and reintroduce it to the wild, comparable to the endangered species recovery efforts with the California condor and the whooping crane.11

the fungus literally results in a white nose on affected bats

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service , Little brown bat with white-nose snydrome

The commercial caves in Virginia, such as Luray Caverns, never closed while white-nose syndrome spread across Virginia. No commercial cave in Virginia could afford to shut down for an indefinite number of years, until some mechanism to eliminate the pathological fungus or mitigate its impacts could be developed. Even the National Park Service kept Gap Cave open in Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, though it did ask visitors to wear clothing that have not been in other caves.12

By 2012, groups such as the Virginia Speleological Society (VSS) proposed re-opening caves to recreational exploration in the summer, based on the understanding that white-nose syndrome had already been transmitted across Virginia through bat-to-bat contacts. Scientists projected that the endangered Indiana bat species will disappear from much of its natural range, but continuing the ban on recreational caving was no longer viewed as an effective way to limit spread of the disease.13

If recreational caving was permanently banned in Virginia, some transmission of fungal spores might be avoided. However, the current community of committed cavers, organized in regional grottoes, would gradually die out if exploration of non-commercial caves was permanently banned. The loss of the caver community would reduce public support for protection of karst communities from inappropriate development, such as directing stormwater underground in limestone-rich areas. A study of the impacts on cave closures in the Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia concluded that the economic damage was minimal, but other impacts should also be considered:14

The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (now Department of Wildlife Resources) closed caves on Wildlife Management Areas (WMA's) in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The coronavirus was thought to have originated within bat populations in China, and it was possible that infected cavers could re-transmit the virus into Virginia bats:15

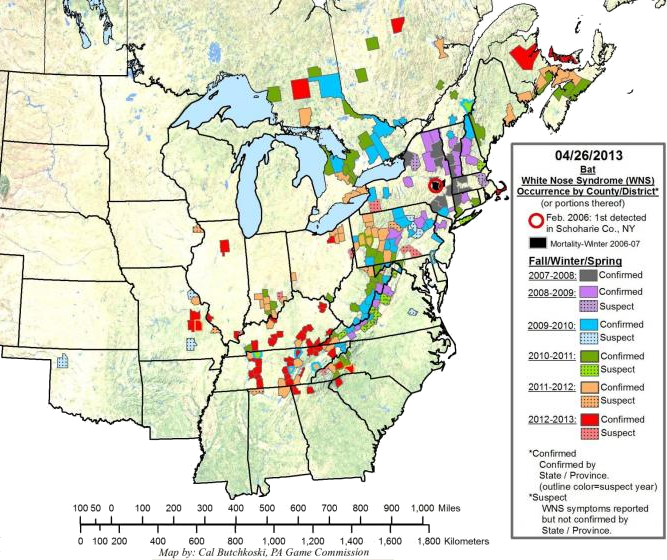

By 2021, the population of the northern long-eared, little brown and tri-colored bats in northeastern state (including Virginia) had dropped by 90%. In 2022, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed reclassifying the northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis), shifting from "threatened" (likely to become endangered) to the more-critical "endangered" (currently in danger of extinction) status:16

Possible responses to the white-nosed fungus included bathing bat roosts in ultraviolet light and using a clay powder to facilitate growth of beneficial bacteria on the skin of bats. One option was to add artificial lights near the mouths of caves to increase the population of flying bugs, allowing bats to eat more before the fungus caused weight loss during hibernation. A scientist at Bat Conservation International said:17

A vaccine, created by genetically engineering a virus to express fungal antigens, offered one ray of hope in dealing with the extinction-level threat. The first tests required administering the vaccine in 2023 to individual bats caught in caves. To be practical, a more efficient technique would be required. Possibilities include a spray or paste which could be spread within a colony of bats as they groomed each other.

Despite the challenges ahead, one endangered-mammals specialist said back in 2012:18

Scientists sequenced the DNA of the fungus and determined that the samples collected in North America were all clones, derived from a single spore of Pseudogymnoascus destructans that traveled from Ukraine before 2006. Most likely, the spore came from the gear of a caver.

Further research revealed that Pseudogymnoascus destructans is actually two species, labelled initially Pd-1 and Pd-2. Pd-1 had caused white-nose disease across North America If Pd-2 managed to reach the continent and land on a a bat, the few survivors could be vulnerable to a second round of infection.

The best way to prevent extinction of already-diminished population of several bat species was to prevent the arrival of Pd-2. As one scientist noted:19

By 2025, the largest hibernating group of little brown bats was at Woods Cave in Page County. The size of the hibernacula was less that 10% of the size of the largest bat community in Virginia prior to white nose disease, but the Department of Conservation and Recreation determined that the population had been increasing steadily for the last decade.20

where northern long-eared bats roost and breed in Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, NLEB Winter Habitat and Roost Trees

Virginia Big-eared Bat

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service