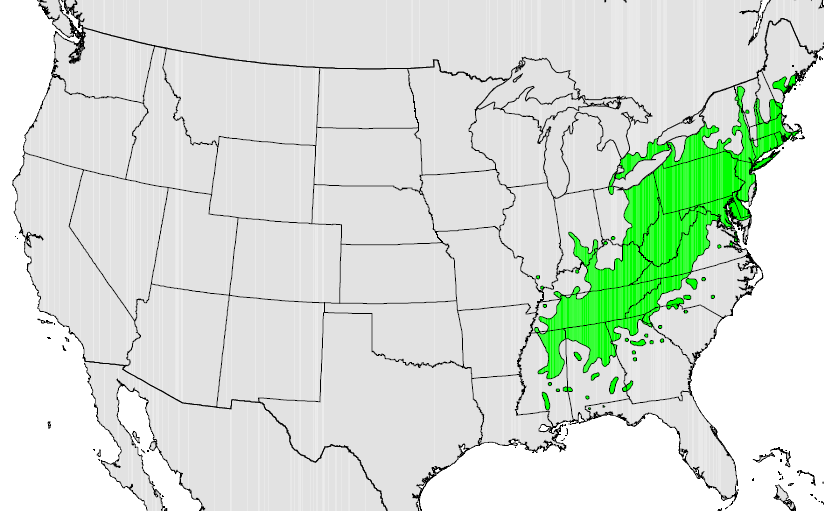

historic range of the chestnut, before the blight

Source: US Forest Service, Atlas of United States Trees

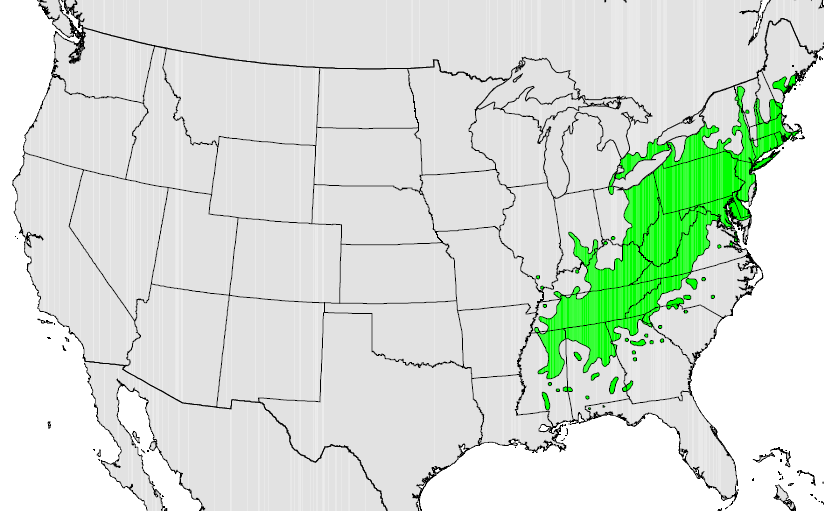

historic range of the chestnut, before the blight

Source: US Forest Service, Atlas of United States Trees

A century ago, 20-25% of the trees in the Appalachian forests of Virginia were American chestnuts (Castanea dentata). It was the dominant "keystone" species that shaped the development of the other plants and animals around it. The nuts were the primary mas crop upon which elk, deer, black bear, and other species depended.

For 18,000 years after the Ice Age ended, chestnut trees which had survived near the Gulf of Mexico expanded their range north. By the time Europeans colonized Virginia, the range of the species stretched from Mississippi to Maine, covering 200 million acres. Within that range there were four billion chestnut trees.

Reflecting the range expansion after the ice sheet retreated, genetic diversity is greatest in the south and southwestern portion of the range. Only one of the four haplotypes found at the southern end of the range grows north of Virginia.1

There is a second Castanea species in Virginia as well, Allegheny chinkapin (Castanea pumila). The range of a third species, the Ozark chinkapin (Castanea ozarkensis), is west of the Mississippi River.

Unlike the chinkapins, the American chestnut has more than one nut per bur on the tree. Typically there are three nuts in each bur. The male flowers are located on long "catkins" which form in June-July, after all danger from frost has passed. Female flowers are located at the base of the catkin.

Trees have both male and female flowers on their individual catkins, but pollen from another tree is required for fertilization. Wind transports the pollen as much as 500 feet, so reproduction from nuts requires trees to be located near each other.

monoecious chestnuts are self-incompatible; female flowers at base on long catkins must be pollinated from other trees

Source: Wikipedia, American chestnut flowers 2 (by Fungus guy)

The alternative form of reproduction was from sprouts, emerging from buds near the root collar. Sprouts are triggered after damage to a tree, and can grow as much as eight feet tall in just one year. After forests were cleared in the 1800's, chestnuts resprouted faster than other species regrew from nuts/seeds. Chestnuts could become almost 100% of the trees in second-growth and third-growth stands.

Typically, American chestnuts were co-dominant species with Northern red oak (Quercus rubra), chestnut oak (Quercus montana), hickory (Carya sp.), and white oak (Quercus alba). On dry sites, it shared canopy space with Pitch pine (Pinus rigida) and chestnut oak. On wetter sites, chestnuts were associated with tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), American beech (Fagus americana) and sugar maple (Acer saccharum).

Young chestnut trees had relatively thin bark, so they were more vulnerable than other species to fire. However, fast resprouting led to an increase in the percentage of chestnuts in Virginia forests once Native Americans began managing vegetation with fire. Native Americans also purposely killed mature trees to stimulate new sprouts, "coppicing" a grove every 20-30 years to increase production of the nutrient-rich nuts.

In natural forests without timber cutting, chestnuts grew slowly as an understory tree. Young chestnuts that managed to survive in the shade could wait for up to three decades for a storm or other event to create a natural clearing and provide needed sunlight.

Chemicals produced naturally within the tree resisted attacks from insects and growth of fungus. Large fallen branches and tree trunks required a long time to decay on the forest floor.

Once a chestnut sapling was in direct sunlight, it could put on a rapid growth spurt and exceed the height of nearby oaks and maples. The species requires full sun to produce nuts. Maturing chestnuts dropped nuts that grew into new chestnut saplings. They would wait their turn, maintaining the dominance of the species in the mountain forest.2

Because the chestnut tree flowers develop late, long after spring frosts, Virginia's turkeys, deer, bears, and other forest wildlife could rely upon a steady supply of nuts for food. Vast amounts of protein covered the forest floor, after nuts fell each fall. The nuts of the chestnut tree were so rich in protein and oils, colonial settlers often left mature chestnut trees in their woodlots to produce annual nut crops for both people and pigs. Collecting nuts in the winter provided farmers a cash crop in a season when the farmers had were not already busy with planting, weeding, or harvesting.

chestnuts at the Lesesne State Forest produce seeds, but no seedlings grow in the understory

When harvested, the bark was rich in tannins, used for making hides into leather. The chestnut wood was easy to split and highly-resistant to rot. Even today, there are skeletons of 100-year old chestnuts on the ground in the Blue Ridge, still resisting decay. Root rot from a fungus-like organism, the oomycete Phytophthora cinnamomi, began to kill American chestnuts after it arrived in the early 1800s from southeast Asia.

The major threat to living trees was Cryphonectria parasitica (known until 1978 as Endothia parasitica), a fungus common in China and Japan. The chestnut blight was first discovered in chestnuts growing at the Bronx Zoo in 1904. William Murrill, a Virginia mycologist working at the New York Botanical Garden and known as "Mr. Mushroom," determined the cause. The blight spread throughout the eastern United States, with spores spread by wind and birds. It took about 20 years to reach Virginia.3

wild chestnut (Castanea dentata)

on Warspur Trail near Mountain Lake (Giles County)

Perhaps four billion chestnut trees were killed by the foreign fungus in 50 years. By 1950, nearly all mature chestnuts across the Eastern United States were dead.4

dead chestnuts once stood as sentinels of the blight

Source: Library of Congress, This Ghost Forest Of Blighted Chestnuts Once Stood Approximately At The Location Of The Byrd Visitor Center

The American chestnut could cope with American forms of the fungus, growing "wound tissue" to isolate a part of the tree where local diseases had entered through a crack in the bark. Similarly, the Asian version of the chestnut tree (Castanea mollissima) could resist the Asian fungus.

The Chinese species is "resistant" but not "immune." Though Chinese chestnut trees get infected by the blight, normally they do not display obvious cankers. However, the Asian version of the fungus grows too fast for the American chestnut tree's defensive response.

The Asian fungus releases oxalic acid that kills the tree's living cells, just inside the bark layer. In American chestnut trees, the Cryphonectria parasitica fungus circles the entire trunk and girdles the tree, blocking the flow of water up to the leaves via the xylem cells and blocking the flow of photosynthesized food from the leaves to the roots via phloem cells. A visible canker on the bark shows where the fungus is active inside the chestnut.

The Asian form of the chestnut blight fungus grows through the American chestnut tree's cambium cells faster than the tree can respond by creating callus (wound) tissue to wall off the disease.5

Above the site where the tree has been girdled by the fungus, an American chestnut will die. Below the infection site, the chestnut tree's roots usually survive because the fungus does not live in the soil. Below the root collar, the roots can resprout. Typically a young chestnut tree matures until a crack in the bark allows a new infection, and the cycle repeats itself. As a result, we still see small chestnuts growing in Virginia forests today.

Fungal spores appear to be unable to get through the protective bark until the branches of the saplings reach a certain size. Near the age when a tree flowers and produces nuts, the expanding trunk naturally creates cracks in the bark. Also, after a certain number of years, a tree may experience naturally-caused wounds as branches rub against each other during a storm in the woods, or as something bumps against the tree. The cracks open up an avenue for infection. The fungus grows under the bark, blocking the flow of water and nutrients from the roots and killing the sapling... but if the sapling's leaves sent enough food down into the root system, the chestnut can sprout over and over again.

Dead chestnut trees used to litter the forest floor. They were recycled into wood products or used for firewood in the 1920's and 1930's. The remnants have rotted away, though a few chestnut fence posts may still be in place. Hikers exploring the woods today will find large rotting trees, but they are recently-fallen oaks, hickories, maples and pines rather than ancient chestnuts.

The American chestnut is not an endangered species, or threatened with extinction. There are millions of small, young chestnut sprouts - and a few large, nut-producing trees - growing in the Virginia woods now. Resprouting chestnut trees die from deer browsing or the effects of the expanding fungal infection, but a few mature enough to produce nuts first. Those nuts carry the genes of the parents, and seedlings from the still-surviving chestnuts are just as susceptible to the blight. Today, the chestnut is a minor component of the understory, no longer a dominant species that affects the surrounding forest.

Many American chestnut trees survive as mature individuals because they have been planted outside their normal range, away from the fungus. The largest chestnut tree ever documented in North America was located in Sherwood, Oregon. Despite efforts of western states to impose plant quarantines, and the pattern of wind from west to east, the fungus may still spread across the continent to infect the chestnut trees now on the West Coast. No American chestnut tree is safe from infection.

canker damage

canker damage

Source: USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org (by Joseph O'Brien)

Prior to 1904, the blight from Asia may have been imported multiple times along with Asian chestnuts into San Francisco or Seattle - but since there were no native chestnuts on the West Coast, the disease could not spread from there.

It is possible that the fungus arrived on chestnuts imported for food, or on 1,000 Japanese chestnut trees (Castanea crenata) sent to a New Jersey nursery in 1882. Asian trees stopped growing at about 40 feet, while American chestnuts grew to 80-100 feet. Orchardists were importing Asian species and trying to create commercial chestnut farms using the easier-to-harvest Chinese and Japanese chestnuts.6

Importing foreign chestnuts for hybridizing with the native American tree has a long history. Thomas Jefferson imported chestnuts from Europe to Monticello.7

chestnuts are still roasted and sold on streets in China

Source: Bernard Spragg, Flickr

An infected chestnut, or infested tree, reached Bedford, Virginia in the early 1900's. The logical place for an infection to appear at that time in Virginia would have been a port city, perhaps Norfolk or Alexandria. Bedford had a railroad connection to New York City, so perhaps a train from the Bronx brought the fungus into central Virginia before birds/wind brought it to the Blue Ridge.8

Today, the shipping terminals in Hampton Roads and an international airport such as Dulles are the likely "Ground Zero" for a new species introduction. However, the experience with the chestnut (and with white-nose syndrome in bats and with snakehead fish in the Potomac River) demonstrates that a blight caused by an introduced pathogen can appear anywhere. As the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated in 2020, a foreign bacterium, virus, or fungus can spread rapidly in the United States.

The original range of the chestnut tree species may have extended all the way to the Atlantic Ocean, though they appear to have preferred the dry and acidic mountain ridges. Another fungus-like pathogen (a root rot, Phytophthora spp.) may have limited the ability of the chestnuts to grow in moist soils east of the Blue Ridge starting in the 1800's. Phytophthora kills a tree completely, roots and all, whereas the Cryphonectria parasitica fungus kills only above the canker and allows the roots to resprout.9

Clearing a forest and grazing cattle on a pasture will kill chestnut roots completely; few American chestnut sprouts occur in open fields today. The Chinese chestnut thrives in the sun but grows poorly in shade. After the Phytophthora and the blight wiped out so many trees, odds are good that any healthy-looking chestnut growing today in an open field/subdivision lawn will be an introduced Asian species. A young tree struggling in the forest is likely to be a native American chestnut, destined to die back to the roots within about 10 years.

The American Chestnut Foundation reports that there are still 87 million chestnut trees and sprouts in Virginia, compared to the 500 million to 1 billion chestnut trees in the state prior to the blight. Several hundred of those wild-type trees are producing nuts that can be planted in the 14 Virginia orchards and used in the research for a blight-resistant mix of genes.10

The Virginia forests are still transforming after the loss of the chestnut. Chestnut oaks, red oaks, and red maples have been released by the removal of the chestnut overstory, becoming dominant in different places. However, gypsy moths may suppress the chestnut oaks, maples will be limited by their inability to grow in shade and replace themselves, the hemlock wooly adelgid kills hemlock trees, and oak decline/oak wilt from various causes may constrain the capacity of the red oaks to replace the chestnut.

Before the blight, in White Oak Canyon and other parts of Shenandoah National Park chestnuts and oaks were codominant canopy species. White oaks did not fill in the gaps left by the loss of mature chestnut trees, and the number of chestnut sprouts slowly declined as short-lived sprouts failed to supply enough resources to surviving rootstocks. Birch and maples became more common in Shenandoah National Park during the century after the blight. Growth of early-successional species, altering the species composition of the park's forest, may have been enhanced by excessive deer grazing and the reduction of normal fires.11

Climate change may reshape the area of suitable habitat. Since the wild-type trees rarely produce nuts, there is a low probability that the genes in the southern part of the range will successfully migrate north as global warming alters the environment. Human intervention through seed collection, propagating trees in nurseries, and replanting will be required to conserve the genetic diversity.

Foresters are planning to restore the chestnut by developing a blight-resistant strain, then planting new stands throughout the old historic range of Castanea dentata. The species could become commercially-valuable for lumber and nuts. When some chestnuts which had been planted in Lesesne State Forest died, the Virginia Department of Forestry harvested them and had a local sawmill produce the first planks of Virginia chestnut lumber in the 21st Century.12

both American and Chinese chestnuts typically have 1-3 nuts in each bur

David and Kim Bryant, who had made their money in software development and were looking forward to a "romantic notion" for retirement, planted a commercial chestnut orchard in Nelson County in 2008. They planted 1,600 trees of the Dunstan variety, which was 95% American chestnut with 5% Chinese chestnut genes. They chose to plant 23 acres in chestnuts for the economics and ease of harvest.

David told a reporter that they:13

The first commercial harvest was in 2015, and in 2019 they gathered 15,000 pounds. After a dozen years of growth, each tree was producing an average of 20 pounds of nuts. That was expected to grow to 50-100 pounds per tree, when they were another 20 years older.

Gathering them as they fell in September/October was an exhausting challenge, even with the help of machinery designed originally to collect pecans. Collection was done in the late afternoon, after trees dropped nuts during the day. If a nut was left overnight on the ground, the local wildlife would get it.

Six chestnut growers, including the owners of Bryant Farm, formed the Virginia Chestnuts cooperative to sell their product. Chestnuts are now a specialty crop associated with the holiday season with "chestnuts roasting over the open fire." Large-scale demand for chestnuts disappeared in the 1930's as the supply disappeared, and modern cookbooks lack recipes that use chestnuts as an ingredient.

Source: Virginia Farm Bureau, Chestnut Orchards Bring Back an American Classic

Imported chestnuts are less expensive due to American food safety standards. To distinguish their Virginia-grown product, some Virginia Chestnuts are refrigerated and shipped cold to restaurants. Chestnuts have a high water content and can dry out, affecting texture and flavor. Chestnuts are also cured by a European method, soaking them in a stainless steel drum for seven days to convert starches to sugar. The nuts remain firm and crisp, but with a sweeter taste.

Virginia Chestnuts also offers pick-your-own weekends in the Fall, and sell bags to online customers as well.14

The 2022 Census of Agriculture reported that chestnuts were being grown for commercial sale on 133 acres in Virginia.15

Virginia Chestnuts sells freshly-harvested nuts to online customers

Source: Virginia Chestnuts, Products

most chestnut hybrids planted at the Meadowview Research Farms die from the blight

the Alleghany Chinkapin (Castanea pumila), with less-pointed leaf margins and just one nut per bur, overlaps with the range of the American chestnut (Castanea dentata)

Source: iNaturalist, Alleghany Chinkapin (Castanea pumila) (by Michael Ellis)

the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) has large curved teeth on leaf margins

Source: Wikipedia, Castanea dentata (by Jean-Pol Grandmont)