in 1644, Opechancanough was so frail he had to be carried on a litter

Source: Mary Tucker Magill, History of Virginia for the Use of Schools (1873, p.77)

in 1644, Opechancanough was so frail he had to be carried on a litter

Source: Mary Tucker Magill, History of Virginia for the Use of Schools (1873, p.77)

A dozen years after the 1632 peace agreement, Opechancanough orchestrated another coordinated assault that was launched on April 18, 1644. The 1644 attack killed more colonists than the 1622 attack, but because the English population had grown so much the percentage killed was far less than in 1622.

The wall built on the Peninsula in 1634 had been effective in excluding Native Americans from the Peninsula for a decade, and the 1644 attack did not threaten Jamestown. Instead, Opechancanough's military success was limited to outlying plantations on the frontier or edge of settlement.

The English used the word "massacre" to describe the event, but other terms that could be used include "great assault" or "uprising." Opechancanough's war aims were to re-establish Native American power, which was diminished after the Second Anglo-Powhatan War, and deter English colonists from continued encroachment on Native American lands.

The timing in 1644 was similar to the attack in the spring of 1622. Choosing to attack when stockpiles of food were exhausted from the winter put the tribes at risk of another "feedfight," with English creating hunger by cutting down ripening corn in the fields in the harvest season known to the Native Americans as "nepinough." On the other hand, an assault in April allowed Opechancanough to keep the Native Americans dispersed on their seasonal round of wintertime hunting and less vulnerable to revenge attacks.

The timing may reflect Opechancanough's awareness of civil war in England and his awareness that he was near the end of his life. He had just one last chance to expel the colonists, or at least to force them to restrict their expansion.

The young men in different towns under Opechancanough's control who had matured since the end of the Second Anglo-Powhatan War also may have pushed for an attack as a way to establish their status as warriors. The peace since 1632 had limited their opportunities to demonstrate skill and bravery.1

in 1609, John Smith seized Opechancanough by his hairlock, making him a hostage and shaming the chief in front of his Native American warriors

Source: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (p.18a)

The 1644 attack also failed to force the colonists to change their expansionist behavior. Once again the English retaliated, and over the next two years destroyed the resources controlled by the paramount chief. In 1646, Opechancanough was captured and soon murdered while in captivity.

The remnants of Opechancanough's paramount chiefdom and the English colonists agreed to a peace in 1646. The treaty signed by Chief Necotowance, who replaced Opechancanough, restricted the Native Americans to the north side of the York River.2

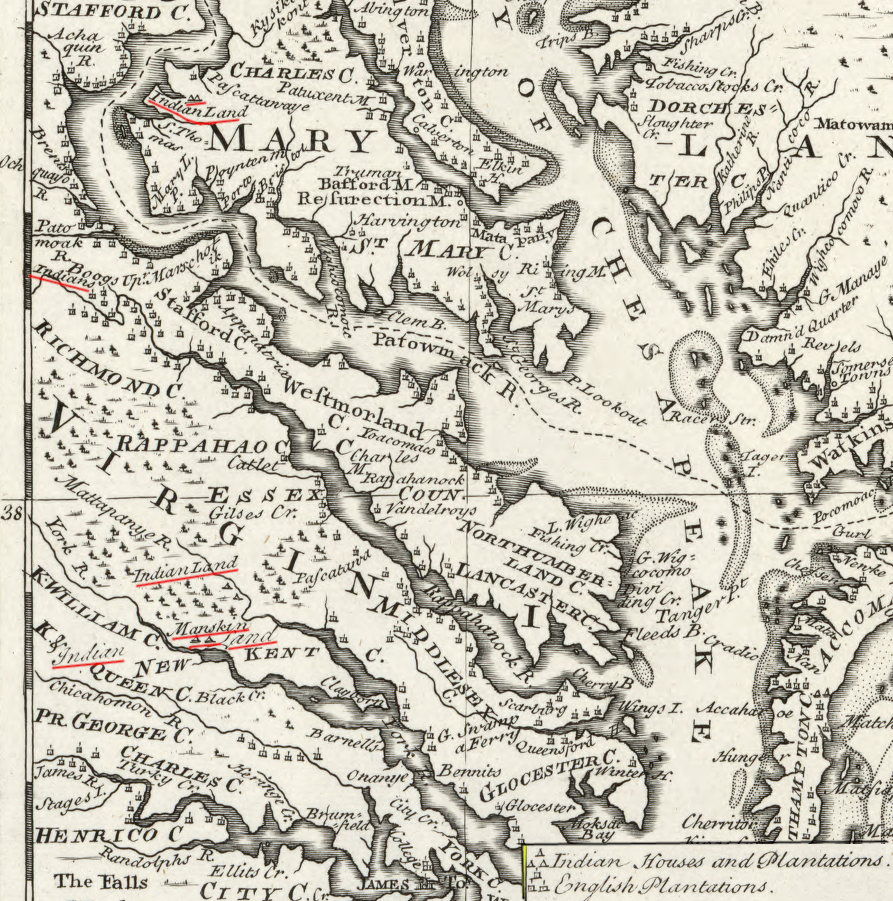

Opechancanough was captured near his fortified town on the Pamunkey River opposite Totopotomoy Creek

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 by Augustine Herrman

a 1752 map documented where Native Americans were concentrated

Source: Library of Congress, A new and accurate map of Virginia & Maryland: laid down from surveys and regulated astronl. observatns. (by Emanuel Bowen, 1752)