Sidney King painting, "Indian Uprising, 1622"

Source: National Park Service - Sidney King paintings

Sidney King painting, "Indian Uprising, 1622"

Source: National Park Service - Sidney King paintings

Opechancanough became the paramount chief sometime after the end of the first Anglo-Powhatan War, perhaps even before Powhatan died. Another brother or cousin, Opitchipan, held the leadership role officially until Powhatan's death in 1629, but it appears that Opechancanough made the key decision to abandon Powhatan's way of dealing with the colonists through negotiations and appeasement.

Powhatan harassed the English in the first Anglo-Powhatan War, killing those who ventured outside the walls of Jamestown as he tried to starve them into submission. He almost succeeded; the colonists were abandoning Jamestown and sailing home in 1610 when Lord De la Warre arrived just in time with new supplies and colonists.

Powhatan then tried diplomacy after the marriage of Pocahontas to John Rolfe in 1614, but the English continued to expand beyond Jamestown. There were roughly 20 settlements stretching up the James River from Point Comfort to Henricus soon after the paramount chief died in 1618. Those settlements were not located in "empty" spaces; the colonial invasion forced Powhatan's people off their traditional homelands.

Opechancanough did not want to submit and passively allow English immigrants to occupy the towns and fields cleared by Native Americans within Tsenacommaco. He chose to use military force to get the colonists to abandon Virginia, or at least adjust their relationship with the local tribes.

By 1616, Opechancanough brought the Chickahominy into Powhatan' paramount chiefdom. He peeled them away from an alliance the tribe had signed with the English in 1614. His success in recruiting the Chickahominy indicates how English expansion was perceived as an existential threat. The Chickahominy, though surrounded by tribes controlled by Powhatan, had never been part of Tsenacommaco. They had been ruled by a council of chiefs that Powhatan had no role in selecting.

Opechancanough was preparing for war.

Personally, he must have still remembered the time John Smith had embarrassed him in 1609, and Powhatan had chosen to move his capital from Werowocomoco to Orapakes. Smith brought the Discovery and two barges up the Pamunkey River to obtain corn in 1609. When he reached Opechancanough's town of Menmend, Smith foiled an ambush. He grabbed Opechancanough by the hair and used him as a hostage. The warriors were forced to load the boats with corn, rather than fight.1

In a culture that placed a premium upon personal capacity as a warrior, Opechancanough must have felt his treatment involved a loss of status that needed to be revenged.

In his lifetime, Opechancanough organized two major surprise assaults on the colonial settlements. The attack in 1622 triggered the Second Anglo-Powhatan War, which lasted for a decade.

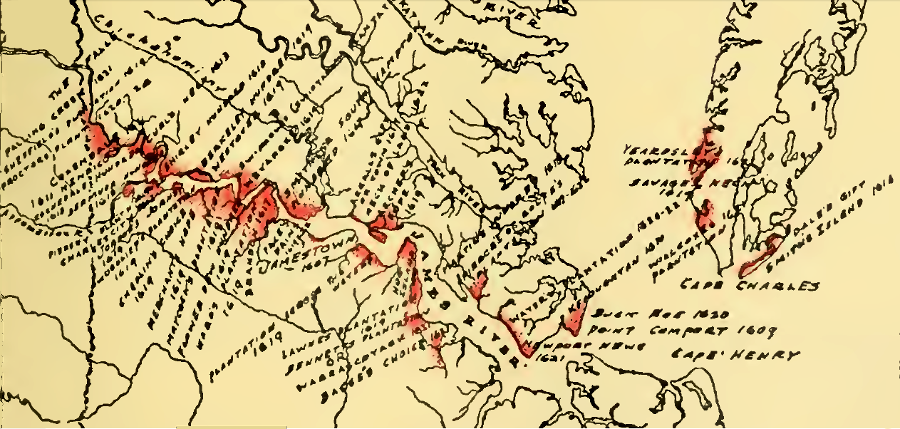

by 1622, colonists had settled along the James River from the Fall Line to the Atlantic Ocean

Source: Nell Marion Nugent, Cavaliers and Pioneers; Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants, 1623-1800 (opposite p.224)

Powhatan's strategy to contain the colonists within a small area of settlement, while extracting valued metal tools and weapons from them, failed because the Virginia Company continued to send people to Virginia. Though a high percentage died and some of the leaders returned to England:2

Opechancanough also sought to protect Tsenacomoco by forcing the English to limit their expansion. His strategy involved a massive use of force, but he first lulled the colonists into thinking their presence had been accepted and their culture would be adopted. The English grew accustomed to the regular presence of Native Americans on the farms and inside houses.

In 1621, Opechancanough secretly coordinated with various tribes his plans to attack colonial homesteads and settlements. During the ceremony for the "taking up of Powhatan's bones," when the Algonquian-speaking groups in eastern Virginia had assembled to relocate the great chief's bones to a final place of honor, he talked in person with different weroances.

A chief from the Eastern Shore revealed the plans. He alerted the colonists that an uprising was being planned, and that Opechancanough was planning to use poison from the water hemlock plant (Cicuta maculata) that was common on the Eastern Shore. After Opechancanough realized the English had been warned, he delayed his attack until the following Spring. He waited until the colonists had relaxed their guard.

Opechancanough had planned in 1621 to poison colonists with water hemlock (above), but his efforts to acquire a stockpile from the Eastern Shore led to revelation of his plan

Source: US Forest Service, PLANTS Database Provides Answers for Vegetative Questions

The assault was launched on March 22, 1622. Nearly 347 English settlers, roughly one-third of the colonists, were killed. Wolstenholme Towne in Martin's Hundred, east of Jamestown, suffered the greatest loss of life; 73 were killed there.

Colonists in undefended farmhouses at the greatest distance from Jamestown suffered severely. The Henricus settlement with its iron furnace at Falling Creek was destroyed. The settlement, planned originally by Sir Thomas Dales as a replacement capital for the colony, was never rebuilt.

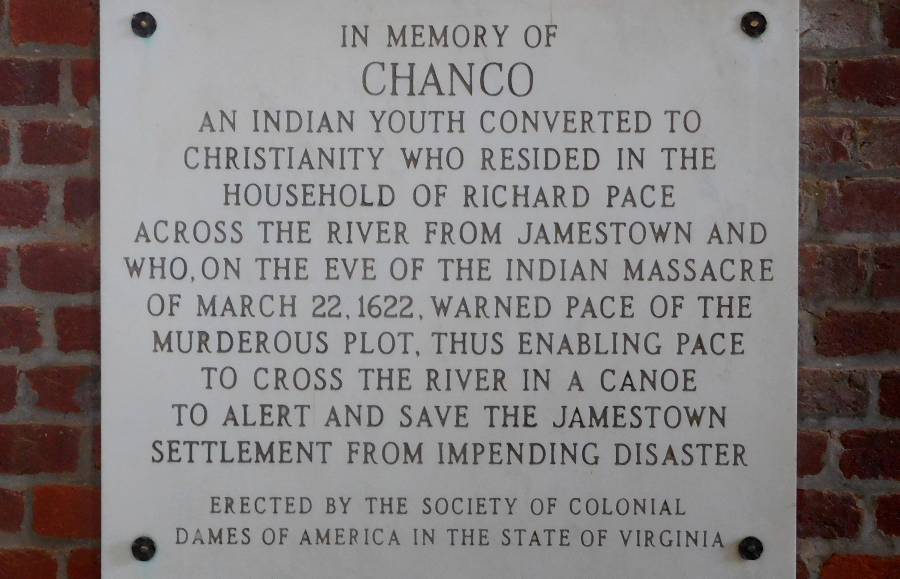

Not everyone chose to follow Opechancanough's orders. Late on March 21, 1622 at least one Native American revealed the assault plans. In Virginia myth one person named Chanco warned Richard Pace, who lived on the south side of the James River. "Chanco" is apparently a conflation of a person named "Chauco" on the Pamunkey River together with a boy who lived near Pace's plantation, both of whom may have alerted the colonists.

Pace warned the settlement at Jamestown, which was not attacked. As John Smith later described it:2

the allegiance of the supposed "Chanco" to the colonists, not to his fellow Native Americans, is honored on the interior of the reconstructed church at Jamestown

Opechancanough could not exterminate the colony, but tried instead to reset the balance of power. If Opechancanough had intended to completely expel the English from Virginia, killing all the colonists until they fled in ships, then he should have followed up with further assaults and even attacked Jamestown. Though the abandoned settlements were burned, he initiated limited attacks on the ten or so plantations where the English had concentrated.

Obviously there are no written records documenting Opechancanough's war aims. Modern historian Frederick Gleach argues that attempts by the English to subvert the Native American religion was one cause for military action. The timing of the assault near Easter may have been a conscious effort to demonstrate that the English religion was not a source of power. George Thorpe, who was the most active colonists proselytizing personally to Opechancanough at Bermuda Hundred, was killed and his body mutilated.

Source: Virginia Museum of History and Culture, The Great Chief Opechancanough and the War for America (Christian Lecture 2022)

Based on how Opechancanough directed the attack and then failed to follow up with more efforts to displace the colonists further, Frederick Gleach suggests:3

schoolbooks until the late 1900's described the 1622 uprising as a massacre, and occasionally depicted the Native Americans in the dress of tribes on the Great Plains

Source: Internet Archive, A School History of the United States, from the Discovery of America to the Year 1878 (p.43)

The attack was the death knell for the Virginia Company. It had failed to generate profits for its investors, and now had failed to protect the lives of its indentured servants and other colonists in Virginia. King James I revoked the charter of the Virginia Company in 1624. Virginia became a royal colony and the king began to appoint the governor, Governor's Council, and other colonial officials.

The Native Americans lacked the resources to support sustained warfare after the March 22 attack. Opechancanough did not have the resources to besiege Jamestown as Powhatan had done in the first Anglo-Powhatan War of 1609-13. Sir Francis Wyatt, the governor appointed by the Virginia Company, still fled to the Eastern Shore for six weeks.4

engraving of 1622 uprising suggests the violence expressed against the colonists

Source: Brown University, John Carter Brown Library, Massacre at Jamestown, Virginia, 1622

Governor Wyatt agreed to a peace treaty in early 1623. Opechancanough offered to return all captured prisoners, and each side proposed they be allowed to plant and harvest corn in peace.

The English had no intention of complying with the deal. On May 22, 1623, an English party led by Captain William Tucker came to the confluence of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi rivers (West Point) to collect the prisoners. Tucker offered Opechancanoe and others some wine for a celebratory toast, but Dr. John Potts had poisoned it. As the poison took effect, the English opened fire. Opechancanough was wonded, and perhaps 50 others were killed.

The colonists had the capacity for low-level, sustained warfare they described as "feedfights." Under Sir George Yeardley, who arrived as the royal governor in 1625 after the Virginia Company's charter was revoked, the English retaliated for 10 years. They continued widespread destruction of Native American towns, stealing and cutting down hard-to-replace crops as well as easy-to-replace thatch buildings.

There were intermittent raids in the spring, when Opechancanough's food reserves were low before crops were planted. More raids were launched in mid-summer when corn fields could be cut down, and then again in the fall when the destruction of towns and food storehouses would have the greatest impact.5

There was one unusual battle in 1624 when about 800 Indians battled 60 English soldiers for two days. The mismatch between arrows and guns determined the winner. The Indians suffered heavy casualties, but just 16 of the English were wounded.

After that battle, it was the English who chose to continue the war rather than negotiate a peace. They raided across Tsenacommaco at will, using their ships at reach waterfront towns and seize corn when it was ripe. The members of the Governor's Council used that corn to feed their indentured servants, which resulted in more tobacco and more personal wealth for those who led the raids. The colony developed a more-stratified society than what existed before the Second Anglo-Powhatan War.6

In 1624 the General Assembly proposed building a wooden wall stretching from the James to the York River, with blockhouses every few hundred feet, to block any Native Americans from living on the eastern edge of the Peninsula. Back in 1611, Sir Thomas Dale had proposed purging all of Powhatan's people from the Peninsula. He recommended to the Virginia Company that it seize:7

To deter further attacks by Opechancanough, colonists were directed to surround their individual houses with wooden walls. Settlements ion narrow peninsulas were given the option of erecting walls across those peninsulas.

To implement a wall across the entire Peninsula, as first proposed in 1611 by Sir Thomas Dale, the 1624 General Assembly agreed to give 50 acres to entice people to settle just behind the wall. Governor Wyatt endorsed construction of a palisade between the James and York rivers, writing back to London:8

Governor Wyatt walso wrote:10

Converting the idea of a wooden palisade across the Peninsula into reality was a slow process. Back in 1611 Sir Thomas Dale could use the indentured servants of the Virginia Company to quickly enclose the much-smaller peninsula on which he built Henricus. After 1624, however, the royal government in the colony lacked direct control over sufficient manpower to duplicate Dale's approach.

Colonial leaders decided again in 1629 to block any Native Americans from living on the eastern end of the Peninsula. In 1630, an attempt to establish control of the northeastern edge of the Peninsula near the mouth of the York River was increased by once again offering 50 acres of free land to those willing to settle at Kiskiack. (Today, that tribe's lands are part of the US Naval Weapons Station near modern Yorktown. "Cheescake" Road is a modified version of "Kiskiack.")9

The feedfights initiated by the colonists diminished as some colonial leaders began to trade with the remaining components of Opechancanough's paramount chiefdom for furs. William Claiborne established a settlement on Kent Island to trade with the Susquehannocks at the northern end of the Chesapeake Bay.

In 1632, the colonists reached a peace agreement with Opechancanough that excluded Native Americans from the lower half of the Peninsula. To control access, the General Assembly finally approved building a wooden wall between the James and York Rivers and expanded the offer of 50 free acres to those willing to settle near the wall.

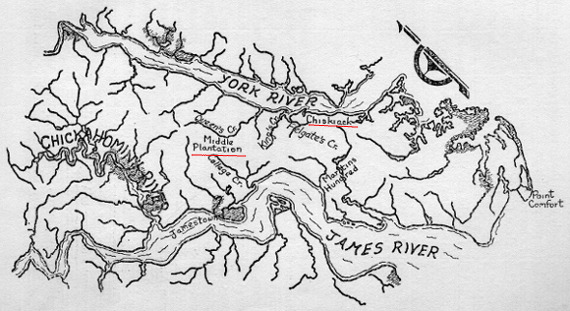

after the 1622 attack, the English settled Kiskiack (Chiskiack) and planned barricades to exclude Native Americans from the eastern portion of the Peninsula, ultimately leading to the settlement at Middle Plantation in 1634

Source: Virginia Under Charles I and Cromwell, 1625-1660

Behind the wall, a new community was established on the watershed divide. Middle Plantation (later named Williamsburg) was in the middle on the peninsula between Archers Hope Creek (now known as College Creek) on the James River and Queens Creek on the York River.

Using a wall for defense and defining a boundary was not new. Native American towns used palisades for protection, Jamestown had a fort with wooden walls, and before 1620 wooden barriers had been erected at Henricus and Bermuda Hundred to enclose small peninsulas.

A wall between Martin's Hundred to Kiskiack had been proposed soon after the 1622 attack. Governor Francis Wyatt noted the colony's plans to move inland from the James River near Jamestown, and to plant settlements north across the Peninsula up to Kiskiack (Chesekiacque) on the York (Pawmunka) River:11

The location of the barrier was moved further west, before approval in 1633. The extra decade of warfare had allowed the colonists to expand their control over the Peninsula; by 1632, the General Assembly included two representatives elected from the area around Kiskiack.12

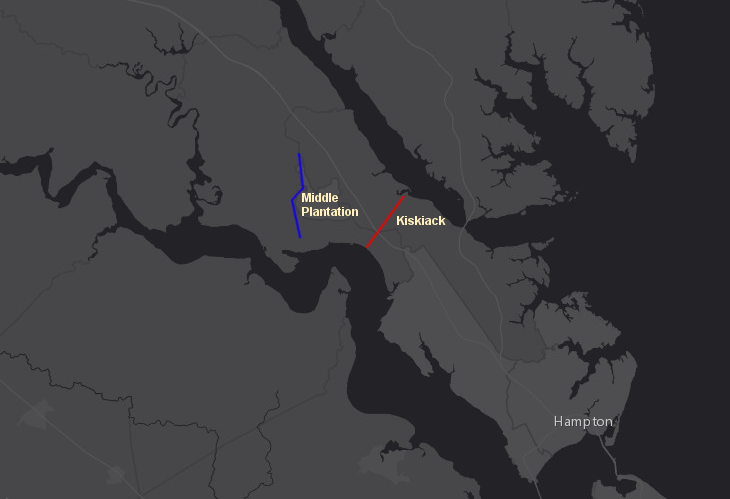

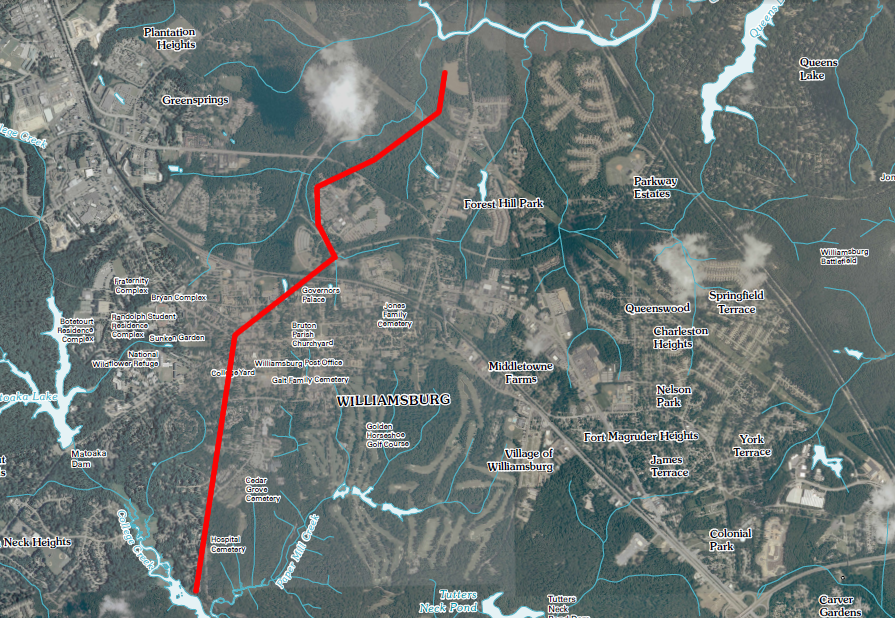

a barrier between Martin's Hundred and Kiskiack was proposed in 1624 (red line), but the wall built in 1634 (blue line) enclosed more acres on the Peninsula

Source: location of 1634 palisade from Phillip Levy, A New Look at an Old Wall. Indians, Englishmen, Landscape, and the 1634 Palisade at Middle Plantation (overlaid on map from ESRI, ArcGIS Online)

Architecturally, the wall across the Peninsula reflected the limited labor and materials available in a colony only 25 years old:13

approximate route of 1634 palisade across the Peninsula, cutting through modern-day Williamsburg

Source: location of palisade from Phillip Levy, A New Look at an Old Wall. Indians, Englishmen, Landscape, and the 1634 Palisade at Middle Plantation (overlaid on USGS 7.5 minute topo, 2010)