Fort Monroe After Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC)

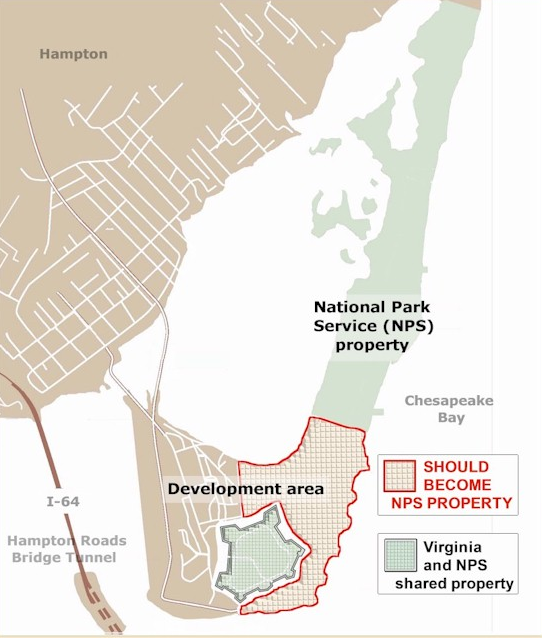

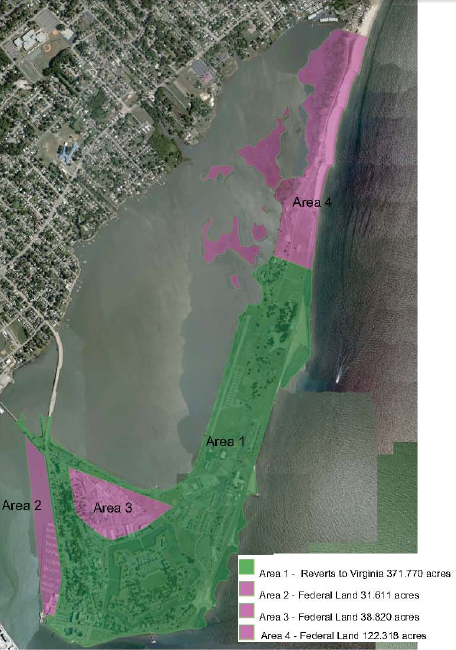

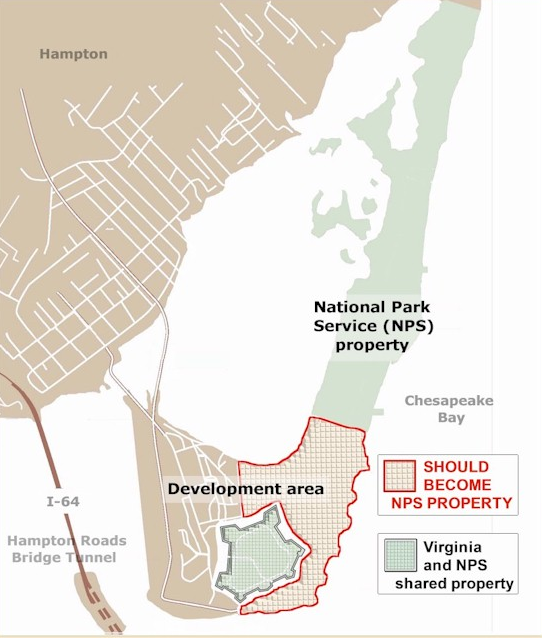

the National Park Service manages the portion of Fort Monroe designated as a national monument (two units separated by the Wherry Quarter), while the Fort Monroe Authority manages the remainder of the land transferred back to Virginia after the military base closed in 2011

Source: National Park Service, Fort Monroe National Monument

After the Cold War ended, the US military planned to downsize and close numerous bases to reduce costs. Department of Defense proposals to shut down existing military facilities were politically controversial, however. No community wanted to lose the economic benefits of the payroll and support contracts, and elected officials sought to obstruct plans of the Department of Defense to shift resources and mothball outdated bases.

To overcome traditional "pork barrel" politics, Congress created the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) decision process. It has been used to identify the most cost-effective ways to consolidate military operations in the United States, while protecting incumbent politicians from charges that they failed in their responsibility to protect local jobs.

Starting in 1988, the Secretary of Defense recommended closure of military facilities and realignment of forces to an independent, bipartisan BRAC Commission in five rounds during 1988, 1991, 1993, 1995, and 2005. The President submitted the final recommendations of the commission to the US Congress as a package, and all of the recommendations automatically have gone into effect. Congress has the option to reject the entire package, but special expedited parliamentary procedures have blocked previous political campaigns of influential officials to isolate one decision and protect one facility.1

The 2005 BRAC process resulted in closure of Fort Monroe in 2011, with the transfer of 3,500 jobs from the base. Of those jobs, 40% were uniformed military and the remainder were civilian/contractor positions.2

Most activities at the base - US Army Training & Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Headquarters, Installation Management Agency (IMA) Northeast Region Headquarters, US Army Network Enterprise Technology Command (NETCOM) Northeast Region Headquarters, and Army Contracting Agency Northern Region Office - were transferred to Fort Eustis. Two units - US Army Accessions Command and US Army Cadet Command - were sent to Fort Knox. Net savings over 20 years from consolidating those administrative operations and shuttering Fort Monroe were projected to be almost $700 million, after cleanup costs for environmental remediation and removal of unexploded ordnance.3

groundwater sampling at Fort Monroe to identify environmental contamination before transfer

Source: Fort Monroe Restoration Advisory Board, Update on Site Investigation (February 7, 2008)

After Fort Monroe was started in 1819, Virginia transferred title of the land underneath the fort to the US Government. The Federal government's right to use land at Fort Monroe was based on an 1838 deed from Virginia, plus the US Army's purchase of additional submerged land in 1908. The 1838 deed required that the land revert back to Virginia once it was no longer used for defense.

The BRAC decision in 2005 triggered that reversion for Fort Monroe.

In 1953 the military had abandoned Fort Wool (formerly known as Fort Calhoun). That fort, built on the Rip-Raps shoal off Old Point Comfort to increase control over the James River shipping channel, was formally returned to Virginia in 1967. Since then, the City of Hampton has leased the island from the state and struggled to get tourists to visit the island.4

The 2005 BRAC process imposed a six-year deadline for transfer of Fort Monroe. Local and state officials knew from the time of the decision that a clock was running - the base would close, jobs would disappear, and ownership of Old Point Comfort would return to Virginia no later than 2011.

Ownership of specific parts of the tip of the Peninsula was complicated by state sale of submerged lands at Mill Creek to the US Army in 1908, and by accretion of land after that date. Since 1819 the military base had been enlarged by both human action (filling in wetlands) and natural accretion.

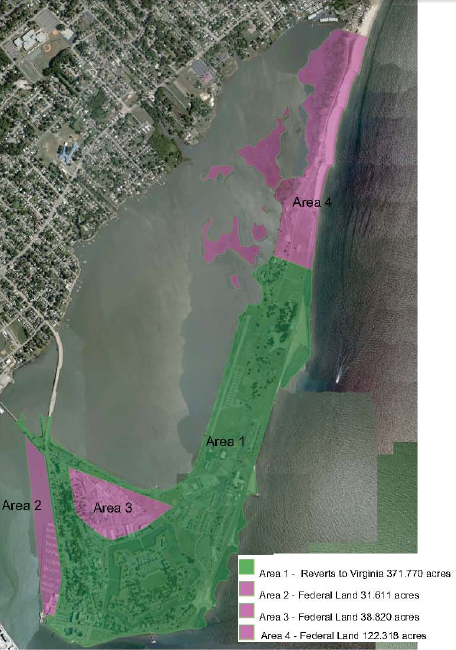

The Department of Defense concurred that the original lands belonged to Virginia, but claimed it was entitled to acreage that had been below the original mean low water line in 1908 and had been created by dumping dirt or naturally "accreted" to the peninsula since then. The Army determined that, based on deeds signed in 1838 and 1936, 372 acres should revert to Virginia but 193 acres were not subject to automatic transfer.

Congress had to intervene and settle the dispute with the 2014 National Defense Authorization Act. Virginia gained ownership of the land (including a 332-slip marina), but will split revenues for future land sale/leases with the US Army.5

Title was finally clarified by passage on the 2014 National Defense Authorization Act. Rather than litigate the issue, the US Army and Fort Monroe Authority agreed to divide future revenue from 70 acres of disputed land (including the 332-slip Old Comfort Point Marina).6

After the BRAC process recommended closure of the fort in 2005, the potential for developing Fort Monroe after the transfer was clear from the beginning. It was "waterfront property in the heart of a metropolitan area." In 2005, private firms involved in reuse of other bases already closed under BRAC envisioned building million-dollar homes and resort communities on Point Comfort.7

Fort Monroe was located within the city boundaries of Hampton. Closure of the base would require the city to provide public services on Old Point Comfort that had been handled by the Federal government since construction started in 1819.

The City of Hampton created the Hampton Federal Area Development Authority to serve as the initial "Local Redevelopment Authority" and started to plan the transfer of responsibilities from the US Army. In 2007 the General Assembly created the Fort Monroe Federal Area Development Authority, replacing the local authority, to increase the role of state officials and the historic preservation community while planning the transfer to state ownership.

By creating the Fort Monroe Federal Area Development Authority, the state assumed greater responsibility to shape the future of the site. The new authority also streamlined the challenge of Federal officials to negotiate with various representatives of local and state government. Both state and local officials sought ways to maintain employment at Old Point Comfort after the military left, and were concerned about the costs to maintain existing infrastructure after Fort Monroe was privatized.

The military base was essentially a town with an expensive backlog of necessary capital improvements and a historic fort in the center. With the loss of funding from the US Army, revenue from the developed area on Point Comfort would not cover expenses for maintenance and public services.

The sewer system required upgrades to reduce inflow and infiltration, the fire hydrant hose fittings were not compatible with the hoses used by the Hampton Fire Department, over 100 homes, and one million square feet of commercial space required maintenance and safety improvements (including lead, asbestos and mold abatement). At one point, a commercial renter had to switch to using generators until electrical service could be upgraded.

A National Park Service "Reconnaissance Study" in 2008 concluded that portions of Old Point Comfort met the criteria for national significance and suitability as a potential unit of the National Park System, but the costs of operating the site would be a major barrier. The study estimated that deferred maintenance costs could reach $130 million, and:8

- It also does not appear likely that a Special Resource Study would find that management, maintenance and operation of the Fort itself (the area inside the moat) by the NPS would be feasible without a strong and financially sustainable partner to offset a large percentage of any capital, maintenance and operational costs.

the Department of Defense calculated that three spots on Point Comfort with a total of 193 acres were not subject to automatic reversion to Virginia, and an act of Congress was required to resolve the dispute over Area 2 and Area 3

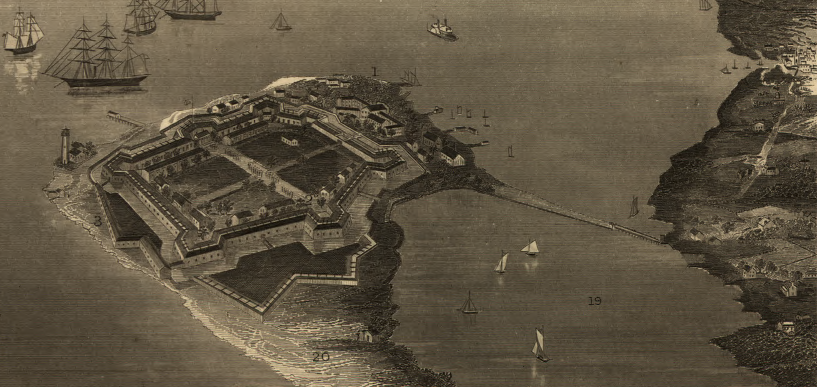

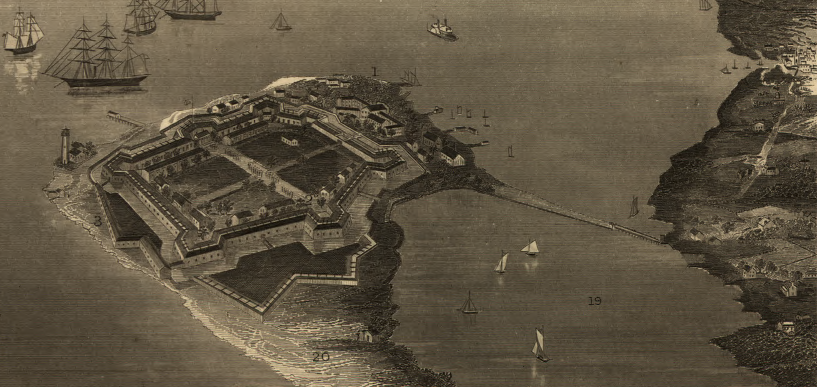

Source: Library of Congress, Fortress Monroe, Va. and its vicinity (1862)

One solution to that problem was to authorize new development at Point Comfort, potentially including waterfront condominiums. There was a consensus that the historic 63-acre stone fort and the northern part of Old Point Comfort, including wetlands near Buckroe Beach, should be protected from new development. What to do with the rest of the base, primarily the residential structures and infrastructure outside the boundaries of the old fort, triggered substantial debate.

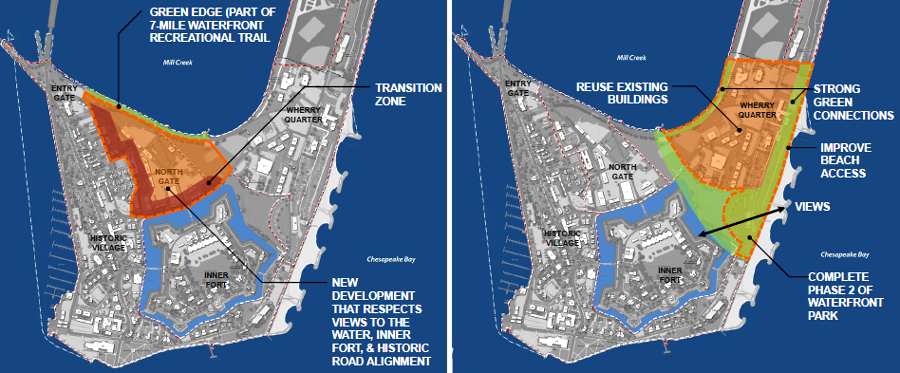

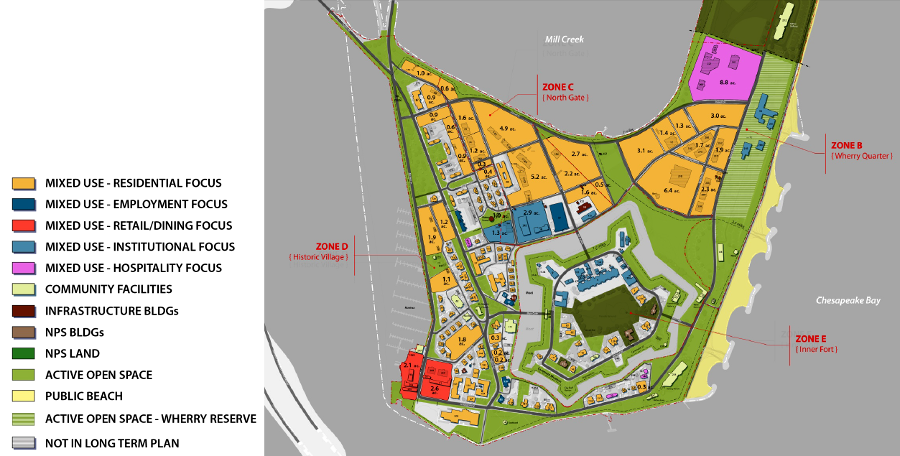

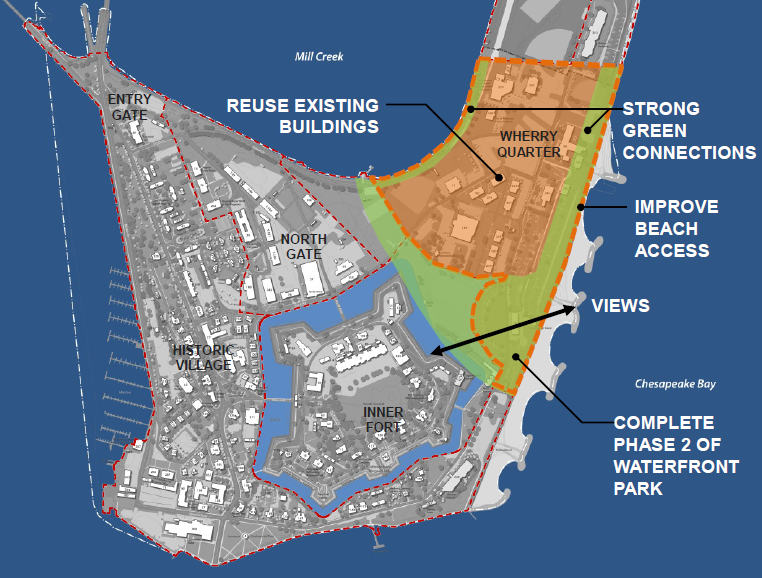

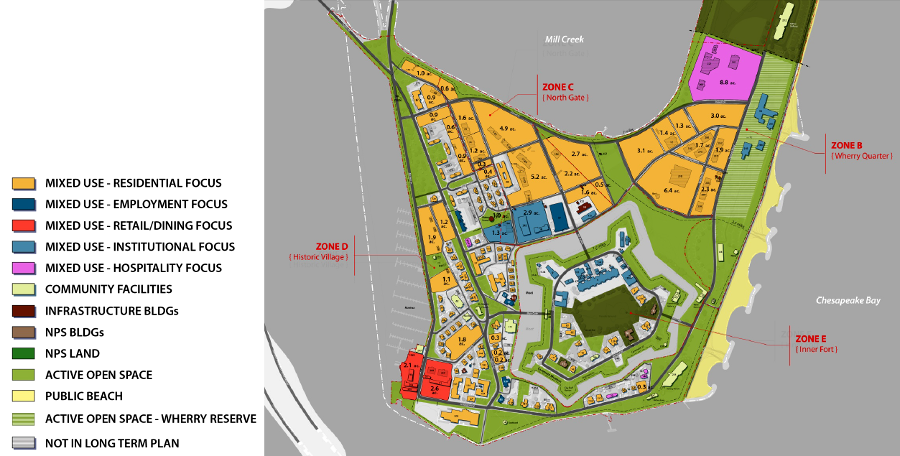

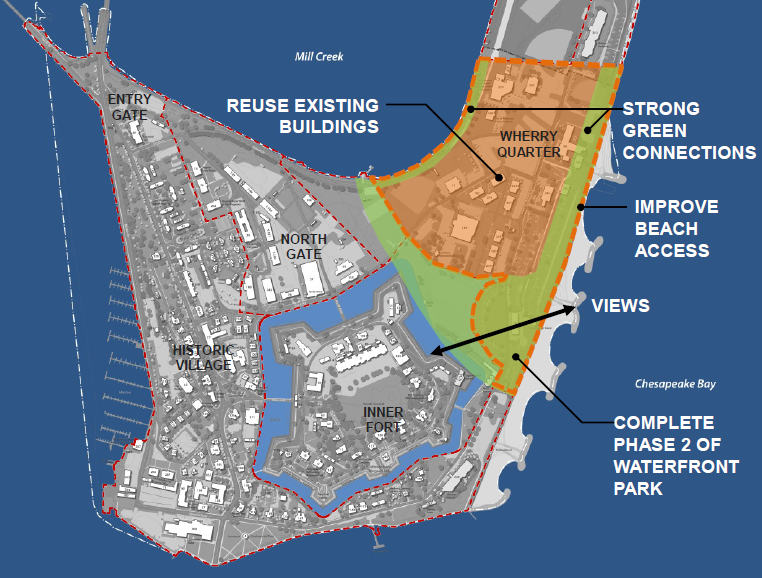

The Federal Area Development Authority was responsible for creating a Fort Monroe Reuse Plan that balanced historic preservation with new real estate development that would generate tax and lease revenue. The authority hired Dover Kohl & Partners, and that contractor produced a Reuse Plan in 2008 that divided Fort Monroe into five land management zones:9

- Inner Fort

- Historic Village and Entry Gate

- North Gate

- Wherry Quarter

- Parks and Recreation Areas

a drawing of Fort Monroe in 1862 shows how little land was available for development on Point Comfort at that time, outside the masonry fort

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Final Environmental Impact Statement for BRAC 2005 Disposal and Reuse of Fort Monroe, Virginia (Figure 2.2-1)

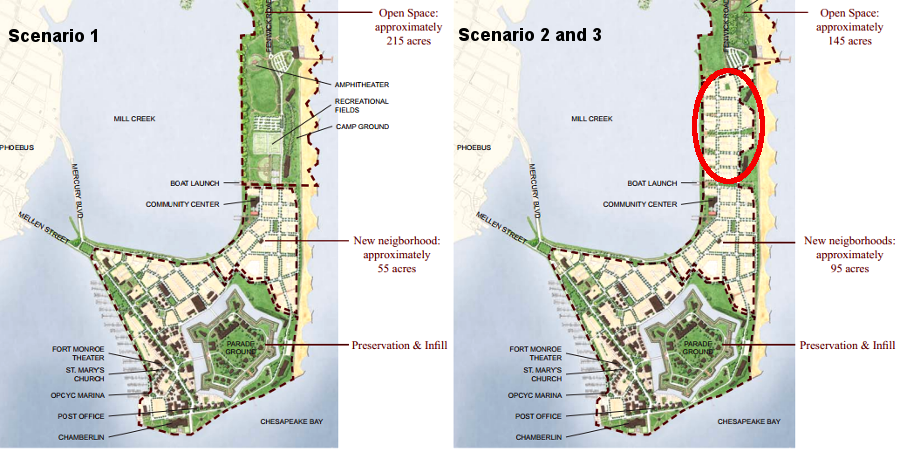

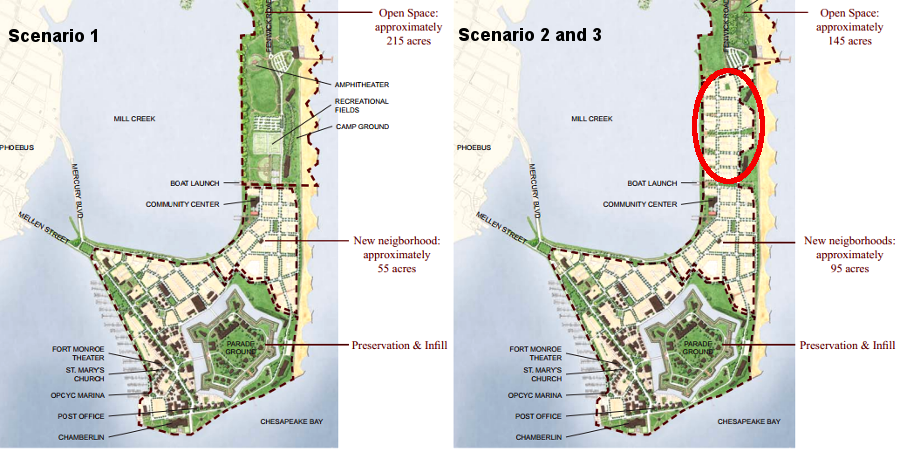

The 2008 Fort Monroe Reuse Plan also proposed three scenarios for redeveloping the military base. Scenario 1, described as the "most curatorial," proposed creating a new 55-acre neighborhood in the Wherry Quarter housing district of the base. The other two scenarios proposed converting 40 acres of open space north of the existing Wherry Quarter into an expanded residential development totaling 95 acres.

Scenario 1 from Dover Kohl proposed 55 acres of residential development at the Wherry Quarter, while Scenarios 2 and 3 proposed 40 more acres of residential development and an equal reduction of open space

Source: Dover Kohl & Partners, Fort Monroe Reuse Plan

The Fort Monroe National Historic Landmark District had been established in 1960, and the fort was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. Federal agencies negotiated with local and state officials to formalize the Fort Monroe Programmatic Agreement in 2009. The Programmatic Agreement, required under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, defined how Federal and state actions would preserve historic resources as the site was redeveloped.

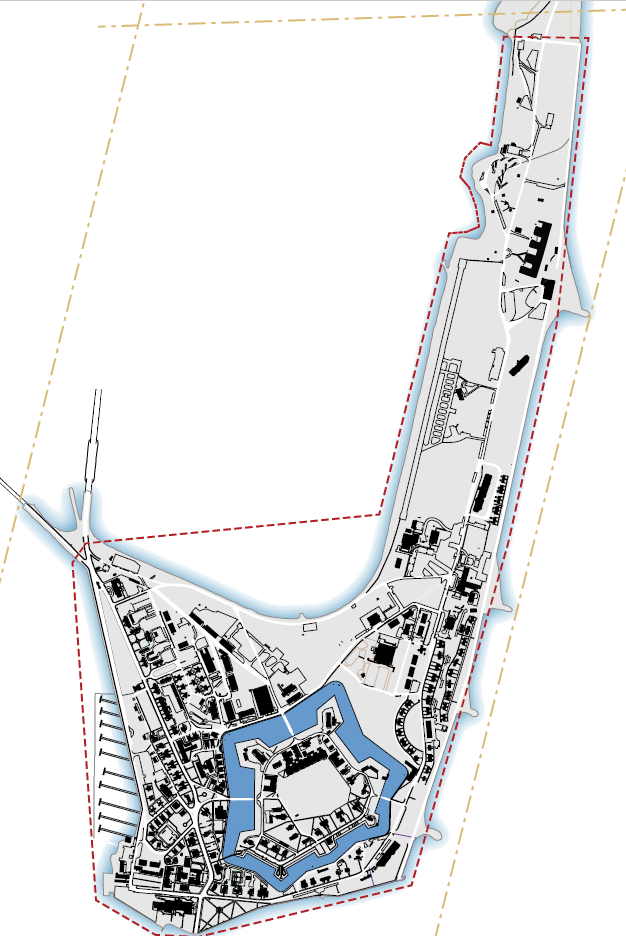

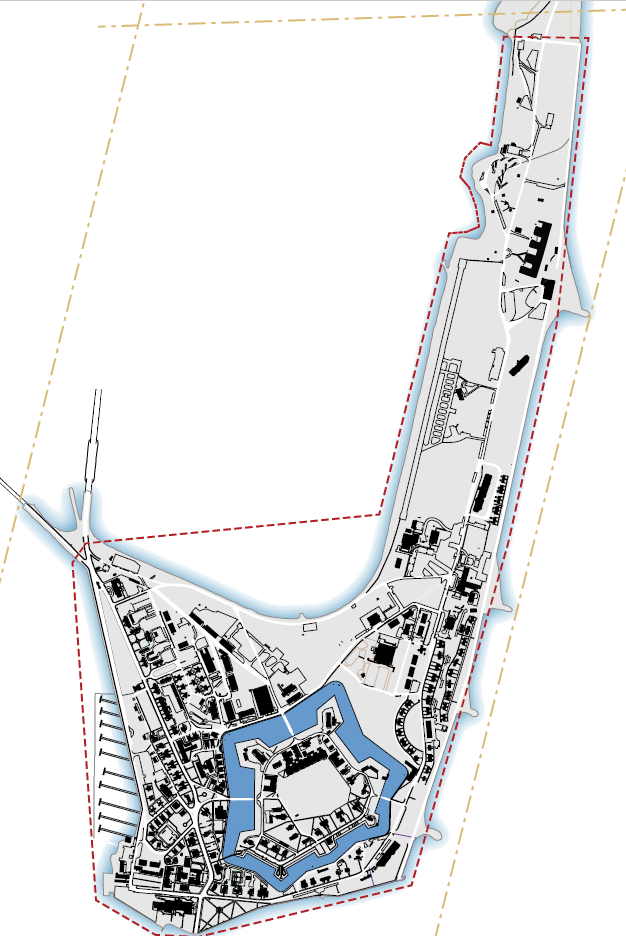

the National Historic Landmark District boundaries include the land within the seawall, up to North (Dog) Beach

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Fort Monroe

National Historic Landmark District

Preservation of the Wherry Quarter was not considered essential to maintain the character of the National Historic Landmark District. Starting in 1953, 53 buildings comprising 206 housing units were built there, and the architecture was functional rather than distinguished. However, the three scenarios in the 2008 Reuse Plan triggered concerns that historic resources would be sacrificed and that high-density development would be excessive.10

Governor Kaine signed the Reuse Plan in 2008. The General Assembly responded by replacing the Federal Area Development Authority with a new Fort Monroe Authority in 2010, and requiring approval of both the governor and the General Assembly before selling any land. The Fort Monroe Authority was tasked by the state legislature:11

- To do all things necessary and proper to further an appreciation of the contributions of the first permanent English-speaking settlers as well as the Virginia Indians to the building of our Commonwealth and nation,

- to commemorate the establishment of the first coastal fortification in the English-speaking New World,

- to commemorate the lives of prominent Virginians who were connected to the largest moated fortification in the United States,

- to commemorate the important role of African Americans in the history of the site, including the "Contraband" slave decision in 1861 that earned Fort Monroe the designation as "Freedom's Fortress,"

- to commemorate Old Point Comfort's role in establishing international trade and British maritime law in Virginia, and

- to commemorate almost 250 years of continuous service as a coastal defense fortification of the United States of America

The Virginia Department of Historic Resources later said about the 2008 Reuse Plan:12

- This agency is on record as strongly criticizing that earlier effort as an inappropriate overlay of "new urbanism."

-

The Fort Monroe Federal Area Development Authority was still in operation in 2009 when it adopted a policy that ownership of the Federally-controlled land at Fort Monroe should be transferred to the state of Virginia, but the historic stone fort, Endicott batteries, and the 1819 structure known as Old Quarters #1 should be managed by the National Park Service. The site qualified for addition to Virginia's system of state parks, but state and local officials supported making Fort Monroe a unit managed by the National Park Service.

State/local officials sought a partnership with that Federal agency in hopes of offloading some maintenance costs and increasing future revenue from tourism. Making Fort Monroe into a "national park" would require an act of the US Congress.13

A local citizens group advocated a public-private partnership with the National Park Service based on the development of the Presidio in San Francisco. The Federal Area Development Authority also considered Colonial Williamsburg as its model for conserving a historic core area while permitting modern development elsewhere to "pay the bills."

The National Park Service suggested the Presidio was an inappropriate model, and that Governor's Island in New York harbor was a better example of how that Federal agency could partner with a state economic development authority at Fort Monroe.

The National Park Service was equally concerned about operating costs, and made clear that it could not offer a financial rescue plan for Old Point Comfort.14

the Fort Monroe Reuse Plan created by the Fort Monroe Federal Area Development Authority in 2008 envisioned creation of a residential community, a new suburb with scenic views, in the Wherry Quarter

Source: National Park Service, Fort Monroe Reuse Plan

In 2011, after announcing the closure of Fort Monroe but before formally transferring the land to Virginia, President Obama used his authority under the Antiquities Act for the first time to create the 325-acre Fort Monroe National Monument. The Congress was gridlocked by partisan disputes in 2011 when the US Army was scheduled to leave the base, and legislative action to designate Fort Monroe as a national park was not a realistic approach. Presidents may use the authority granted in the 1906 Antiquities Act to designate "national monuments" through executive action.

The president placed two separate portions of land under control of the National Park Service. That decision blocked transfer of 325 acres of the 565-acre former military base to the Fort Monroe Authority. The new Fort Monroe National Monument included the 63-acre fort and an undeveloped beach segment north of the Wherry Quarter, but transferred the Wherry Quarter to Virginia.

The Coast Guard retained ownership of the Old Point Comfort Lighthouse. It was built in 1802, and today is "the oldest existing lighthouse in continuous operation on the Chesapeake Bay.15

the US Army transferred land to the state of Virginia (1), the Fort Monroe Authority (2 and 3), and the National Park Service (4)

Source: US Army, Fort Monroe, VA Conveyance Progress Report (2018)

Fragmenting the monument into two parts, with the Wherry Quarter separating the historic masonry fort from the beach, was controversial. A local activist created a preservation group, Citizens for a Fort Monroe National Park, and campaigned steadily to united the two pieces and get the Wherry Quarter added to the monument. The basic argument was that development in the Wherry Quarter damaged the historic view of the Chesapeake Bay from the ramparts of Fort Monroe, and allowing new infrastructure would create future costs to protect against flooding.

Storm surge maps show that Point Comfort will be flooded and isolated from the mainland by the storm surge of a Category 1 hurricane. Point Comfort is also in the "50-year flood" zone, with a 2% chance every year of being flooded. The 1934 seawall, built after the 1933 hurricane, was not sufficient to protect the base during Hurricane Isabel in 2003. A seawall two feet higher was completed in 2009.16

a Category 1 storm will cause flooding across most of Point Comfort

Source: City of Hampton, WebGIS Portal

The local newspapers were split in their opinions regarding development at Fort Monroe. The Virginian-Pilot, the dominant paper in South Hampton Roads, supported expanding the monument boundaries and blocking the Fort Monroe Authority plans to authorize new residential units between the historic fort and the beach segment of the national monument. The Daily Press, the dominant paper on the Peninsula, focused on the financial challenge to make the Fort Monroe Authority self-sustaining and on the potential of development in the Wherry Quarter to generate revenue.

The Virginia General Assembly passed a resolution in 2012 that kept open options for either preservation or development, but called for preserving the Wherry Quarter "to the maximum extent possible."17

In 2012, the Historic Preservation Manual & Design Standards for Fort Monroe were completed. They defined how new structures and alterations to existing structures could retain the historic/architectural character of the site, and what changes would be consistent with the National Historic Landmark designation. The standards called for repairing rather than replacing existing structures, using properties for their historic purpose or for one that required minimal change, and making alterations (such as adding air conditioning or accessibility ramps) that could be removed without altering the historic fabric of a building.

In 2013, Governor McDonnell approved the Fort Monroe Master Plan. It incorporated extensive adaptive reuse of historic buildings rather than preservation of structures without alteration. Reuse was expected to stimulate the private sector to finance maintenance of structures; in contrast, pure preservation would require high levels of local, state, and Federal funding that were not expected to be appropriated.

New construction was authorized as well, provided it was compatible in massing, size and scale as defined through the Historic Preservation Manual & Design Standards. Up to 3,000 new residents could be housed on Old Point Comfort. The Fort Monroe Authority was authorized to lease the commercial properties in the Wherry Quarter, and could sell other lands outside of the old fort moat.18

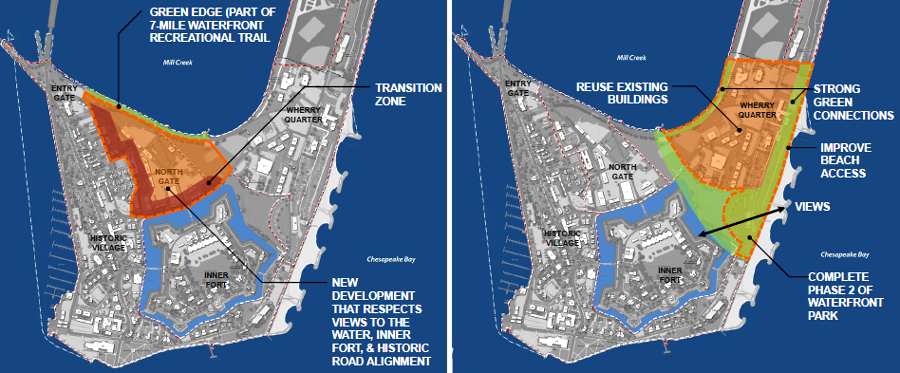

all reuse plans for Fort Monroe include redevelopment of the Historic Village and North Gate zones west and north of the historic fort, but proposals for the Wherry Quarter on the northeast side have generated controversy

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Fort Monroe Master Plan 2013 Presentation

The Master Plan included a 100-yard-wide strip of dedicated green space on the east side of Wherry Quarter (Zone B) to link the two segments of the monument, but kept open the option of redeveloping that zone once existing buildings aged beyond cost-effective repair in 15-20 years. Designation as a national park was seen as desirable, but the Wherry Quarter would be a section of as private land with a new residential development separating any North Beach parkland from the historic stone fort.

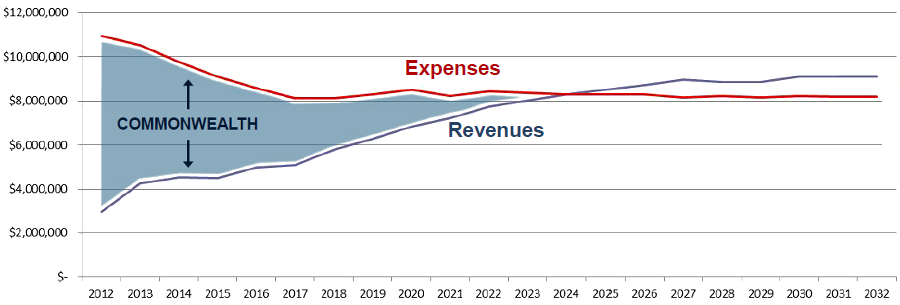

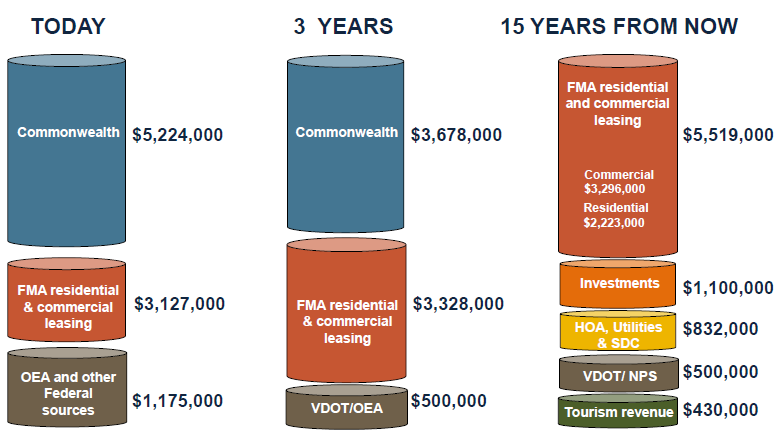

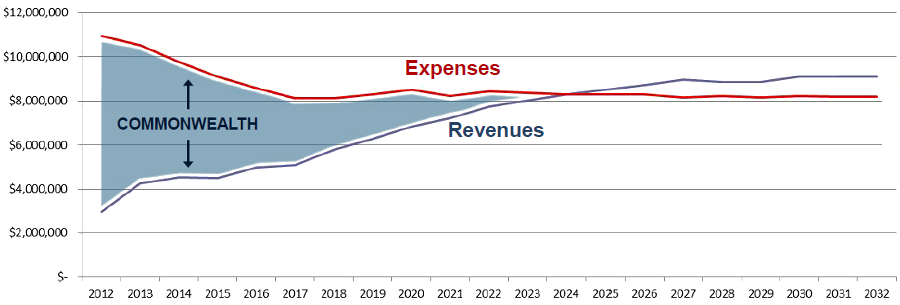

The Master Plan assumed the number of residential units would double in the next 15 years with the construction of 540 new units between 2018 and 2027, and that the Fort Monroe Authority would require a financial subsidy from the state at least until 2024. The Fort Monroe Authority would ultimately transition from a state agency into a property management company and a property owners association.19

the Master Plan proposed the Wherry Quarter (Zone B) should be used for private development, splitting any park into two separate pieces

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Fort Monroe Master Plan 2013 Presentation

between the moat surrounding the historic stone fort and the Wherry Quarter, the Master Plan proposed a park linking the Chesapeake Bay and Mill Creek

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Fort Monroe Master Plan 2013 Presentation

State and local officials sought to create a self-sustaining community to replace the military base. They were unwilling to commit to permanent, taxpayer-funded operations and maintenance to preserve the historical setting without changes.

Historical preservation advocates debated the extent to which change could be acceptable, and the tradeoffs required to provide financial stability for managing the part of Old Point Comfort that was outside the boundaries of any park.

the Fort Monroe Authority does not plan to become self-supporting until 2024 at the earliest, and will require a financial subsidy from the state until then

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Fort Monroe Master Plan 2013 Presentation

The Virginia Department of Historic Resources supported adaptive reuse of the structures and new development at the base as proposed in the Master Plan, rather than the alternative of including the Wherry Quarter within a park. The state agency agreed with non-government organizations involved in historic preservation that long-term protection of the historic resources at Fort Monroe would require creating a self-sustaining community in place of the military base.

As far back as 2008, the Civil War Preservation Trust, National Trust for Historic Preservation, National Parks Conservation Association, and Association for Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (later renamed Preservation Virginia) had agreed funding from general appropriations and grants would not be reliable over the long run. Those organizations chose to support a reuse strategy that excluded the Wherry Quarter initially, because it created "a center of vital and diverse activity to achieve the economic sustainability that will make the highest level of preservation and interpretation viable."20

The National Trust for Historic Preservation stated its support for the Master Plan bluntly:21

- In our view, the draft plan strikes a reasonable balance of historic preservation and compatible change...

- In the National Trust's experience, few historic sites can survive as single-purpose tourism destinations. Across the country many such sites struggle to sustain themselves financially, despite their value to an understanding of our heritage...

- With regard to the Wherry Quarter, the National Trust recommends the FMA [Fort Monroe Authority] continue to utilize the 25 existing buildings located in this 70-acre management zone. These existing buildings are capital assets which should not be wasted. When the useful life of non-contributing buildings is exhausted, the majority of the Wherry Quarter acreage should become parkland to complement the National Monument.

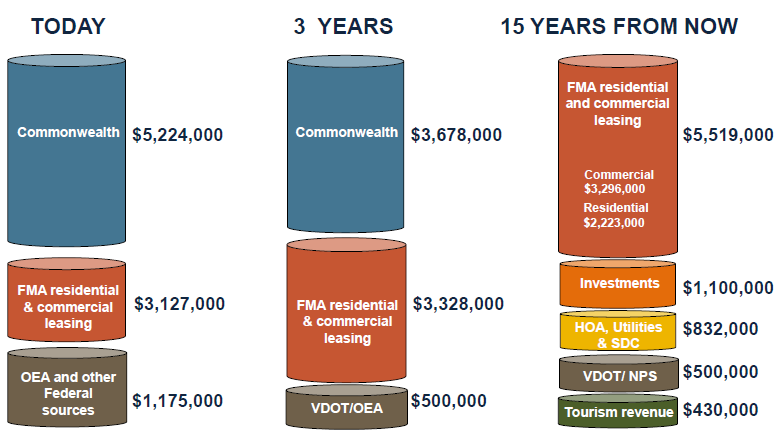

the Fort Monroe Authority plans to generate most of its operating income from leasing/selling residential and commercial real estate, reusing existing buildings and authorizing new construction

(Today=2013, and projections exclude capital costs)

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Fort Monroe Master Plan 2013 Presentation

Storm damage from Hurricane Isabel in 2003 and Hurricane Irene in 2011 forced removal by 2013 of all but one of the 53 original housing units built in the Wherry Quarter after the Korean War. The Master Plan had proposed reutilizing the buildings for up to 15 years to generate income, then replacing them with new development once the Fort Monroe Authority was generating a positive cash flow. Instead, the Fort Monroe Authority faced the challenge of raising funds for new buildings immediately.22

In late 2014, the new governor (Terry McAuliffe) altered state policy when he announced support for incorporating the Wherry Quarter into the Fort Monroe National Monument. The National Parks Conservation Association quickly endorsed his recommendation and The Civil War Trust joined the call within a week. However, in contrast to the united stand of historical organizations 2008, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Preservation Virginia failed to join in. The common effort for historic preservation at Fort Monroe in 2008 fractured by 2014 over concerns for the long-term financial viability of the site without substantial revenue from sales/leases.23

Expanding the boundaries of the monument would eliminate the opportunity for the Fort Monroe Authority to generate revenue from existing buildings over the short-term (10-15 years), then redevelop that acreage with new structures. In exchange, transferring ownership of the land would reduce required funding for operating costs and future capital improvements at the Wherry Quarter, and potentially increase tourism revenue.

The Newport News Daily Press opposed Gov. McAuliffe's decision in an editorial saying:24

- The only way to keep Fort Monroe open and available for future generations is to draw revenue from that property.

- That is best accomplished through thoughtful, limited development on available land that lacks the same historical value that fort itself boasts. Gov. McAuliffe must not let fiscal expediency or unrealistic dreams scuttle a promising blueprint for success.

The Fort Monroe Authority will pursue sales, leases, and redevelopment in North Gate (Zone C) and Historic Village (Zone D), whether or not the Wherry Quarter (Zone B) is transferred to the National Park Service. Historic Village is planned to evolve into a mixed use community with housing, specialty retail, and restaurants, funded in part through adaptive reuse of old buildings with historic tax credits. North Gate is planned for substantial transformation with new structures, consistent with historic preservation design standards.25

plans by the Fort Monroe Authority to obtain revenue from sale/lease of properties in North Gate (Zone C) and Historic Village (Zone D) drew few protests, but the extent of private development proposed in the 2013 Master Plan for the existing buildings in the Wherry Quarter (Zone B) spurred great debate

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Fort Monroe Master Plan 2013 Presentation

The Commonwealth of Virginia played an outsized role in the decisionmaking, because Hampton relied upon state funding to subsidize services (primarily schools, fire/police protection, and collection of garbage) to Fort Monroe through a Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) contribution. In 2015, Hampton lobbied the General Assembly to increase that subsidy, which was almost $1 million annually, and sent a bill for $1.2 million to the Fort Monroe Authority.

When the US government did not pay the bill, the city filed a lien against the property. No court would force payment of that lien, but the city anticipated future costs could grow to $1.6 million annually as more land was transferred from the US Army.

The state legislature declined to increase the funding in 2015, despite support from the governor. The city could revise its own tax rates and update the assessed value of private land at Fort Monroe, but any change in the PILOT payment required action by the General Assembly.26

In 2015, Virginia formally transferred 120 acres of state-owned land within the monument's boundaries to the National Park Service. The Army was required to "remediate" or clean up past pollution at places such as North (Dog) Beach, before the National Park Service would accept ownership.

The US Army retained control of some land within the boundaries of the national monument for a decade after closure of Fort Monroe, until remediation was completed. The Army released 34 acres, including the Old Point Comfort Marina and the moat, in 2019. In 2021, the Army transferred the last land it owned, five acres underneath The Chamberlin, to the Commonwealth of Virginia. That shift in ownership caused the retirement community to send $80,000 annually for use of the land to the state, rather than to the US Army. When signing the deed, Governor Northam joked:27

- More revenue!

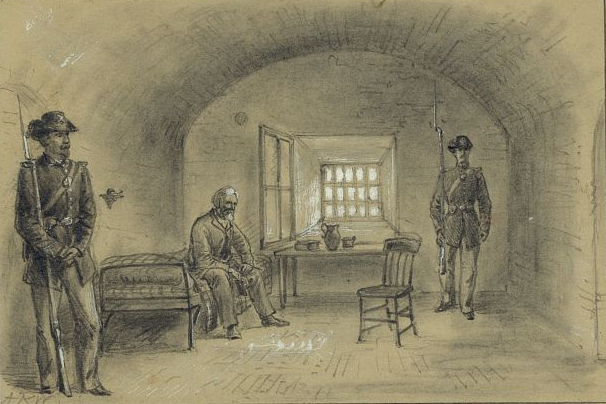

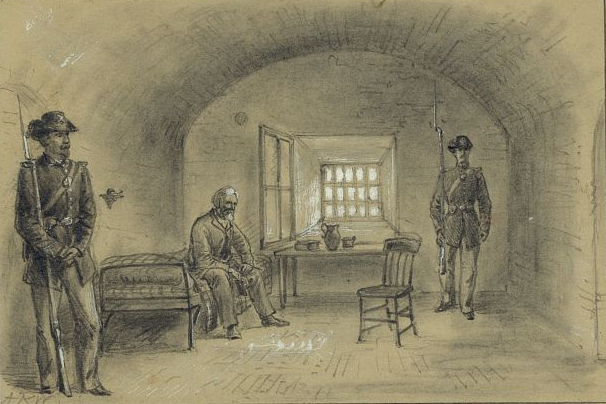

The Casemate Museum, where Jefferson Davis was kept as a prisoner after the Civil War, was retained in state ownership, but with an easement to the National Park Service to protect the site's long-term integrity. Since 2013 the museum has been operated by the Fort Monroe Authority. The authority did not take responsibility for Fort Wool; that remained state-owned land under lease to the City of Hampton.

The state retained control over the land where the United Daughters of the Confederacy had funded construction of a 50-foot high iron arch with letters spelling "Jefferson Davis Memorial Park." That 1956 project to honor the president of the Confederate States of America was associated with the Massive Resistance effort in Virginia and other southern states to block implementation of school desegregation, after the US Supreme Court had issued its first Brown v Board of Education ruling in 1954.

In 2019, just before events commemorating the 400th anniversary first arrival of enslaved Africans at Hampton, Gov. Ralph Northam had the letters removed from the arch and transferred to the Casemate Museum. The arch itself was left standing. The National Park Service had no role in the decision process, since the site identified as Jefferson Davis Memorial Park was not under Federal control.28

harsh imprisonment of Jefferson Davis at Fort Monroe converted his reputation in the former Confederate states from scapegoat to martyr, and that story is told in the Casemate Museum

Source: Library of Congress, The casemate, Fortress Monroe, Jeff Davis in prison

In 2016, the General Assembly stepped in. The state legislators included language in the 2016-18 budget to clarify land ownership at Fort Monroe.

The state agreed to fund $23 million in infrastructure upgrades near military bases, with the most likely candidate for that investment being the road network next to Fort Eustis. In exchange, the legislators required the US Army to cede control over the Chamberlin Hotel and the marina.

The budget language also forced Hampton to withdraw its lien against the US Army before the state would make any future PILOT payments.29

The state budget did not provide any assurance that the Fort Monroe Authority could reach financial stability, and did not resolve how to repurpose the old structures inherited from the US Army. As one Fort Monroe Authority board member noted soon after the General Assembly adjourned:30

- My concern, quite honestly, is we have 110 buildings, 1.2 million square feet of space. ... Unlike other state property, probably half of those have no public use... The question is, How do you deal with these buildings we want to save? ... I don't want to be here in 10 years and having 500,000 square feet of rotting buildings.

advocates for creating a larger Fort Monroe National "Park" sought to transfer the Wherry Quarter and beach property to the National Park Service

Source: Save Fort Monroe

The Fort Monroe National Monument created in 2011 was fragmented into two pieces, with a gap between the stone-walled fort and the beach area to the north. The National Park Service steadily declined opportunities to obtain additional land which would connect the two units, particularly the old structures in the Wherry Quarter, because the Federal agency lacked funding to redevelop or even maintain the buildings which would be transferred.

Despite Federal resistance, there was steady public pressure to connect the two units to create "One Fort Monroe." In 2019, just prior to the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Africans being transported to America to work as slaves arriving at Hampton, Virginia's two US Senators proposed legislation to add 44 acres to the National Park Service unit. The 44 acres included the beach on the eastern side of the Wherry Quarter.31

Once again, the Daily Press opposed transferring the 44 acres to the National Park Service. Transferring the property into Federal ownership could limit the opportunities of state and local agencies to find the needed mix of funding, tax credits, and other incentives to address deferred maintenance.

The editorial highlighted how the Federal government under President Trump had chosen to alter the boundaries of two national monuments in Utah, increasing opportunities for economic development at the expense of natural resource protection. Opening the natural areas in Utah to mining and ranching was controversial because of the significant change in the intent behind creating the national monuments there. In contrast, the 44 acres in question at Fort Monroe National Monument were never intended to be managed for historic preservation or natural resource management; those 44 acres were intended to be redeveloped for economic purposes.

As the newspaper noted:32

- The sole value of those 44 acres comes from their proximity to the beach and the stone fortress. No historic buildings sit on the land; none of Fort Monroe's major historic narratives took place there, and the structures that do exist are either vacant, in need of serious repair or are rented by commercial tenants.

The fundamental issue was not a risk of inappropriate development, but of funding. Neither the Fort Monroe Authority nor the National Park Service had the resources required to redevelop the Wherry Quarter, as was intended from the initial creation of Fort Monroe National Monument.

In 2017, the Fort Monroe Authority had estimated that it needed an additional $2 million annually to maintain 245 buildings, including 147 designated as contributing to the National Historic Landmark District. After Hurricane Mathew, a contractor's assessment documented that:33

- ...the vast majority of the asphalt roofs at Fort Monroe are at or beyond their useful lives.

The National Park Service and the Fort Monroe Authority refined the land transfer as proposed by Virginia's two US Senators, agreeing on 35 acres to be shifted to the Federal agency and a 5-acre expansion of the historic conservation easement boundary at the Casemate Museum. The remaining acreage consisted of Fenwick Road, which the state would retain and maintain. Transferring the beachfront would unite the 112-acre northern beach parcel with the historic fortress, establishing the envisioned "One Fort Monroe." The deal, if approved by the Trump Administration, would also ensure perpetual public access to the entire beachfront by removing the threat that the Fort Monroe Authority might authorize a private redevelopment project which restricted beach access.

Getting that final approval was not assured. The Fort Monroe Authority, in its authorization for the 35-acre land transfer, noted:34

- WHEREAS, in 2018, it is our understanding that certain senior officials of the Department of the Interior have ordered the NPS not to accept donation of the proposed 35± acres from the Commonwealth due to a misperception that the property carries with it excessive deferred maintenance responsibility...

The Trump Administration declined the donation of 40 acres. In response, Senators Tim Kaine and Mark Warner introduced legislation in 2019 to force the Department of the Interior to expand Fort Monroe National Monument and connect the two segments.35

In 2021, Governor Northam announced a $40 million plan to redevelop the Marina District adjacent to the historic Chamberlin. In addition to remodeling the 300-slip Old Point Comfort Marina, a private developer would build a 500-seat restaurant, 250-person event center, and a 90-bed boutique hotel. The hotel would not be a competitor to the Chamberlin, which had been converted into an independent living community for seniors.

the adaptive reuse project was named 37° North by the developer

Source: Pack Brothers Hospitality, 37° North

The developer planned to repurpose the Coast Artillery School Bindery, Old Torpedo Storehouse, and Old Cable Tank Building. The governor's announcement was the culmination of an effort by the Fort Monroe Authority to get adaptive reuse proposals from the private sector.

Planned new construction included a pool, a replacement building for the Old Point Comfort Marina Yacht Club, and a 15,000 square foot outdoor deck on the waterfront. The existing docks and timber wave screen at the marina would be completely replaced.

Using 95,000 square feet of state-owned bottomland for the new marina required approval by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission. That generated controversy when the state agency decided that the redevelopment project was a "governmental activity" and did not require permits or payment for use of the bottomland. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation and Wetlands Watch objected, stating that exemptions for "governmental activity" should be applied narrowly to projects such as new roads and sewers.36

The Fort Monroe Authority advertised a "Request for Real Estate Proposals for the Redevelopment and Adaptive Reuse of Four Sites at Fort Monroe" at the end of 2021:37

- The information in this Request for Real Estate Proposals (RFREP) is designed to present four adaptive reuse sites at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia to the development community. These sites contain a total of 14 buildings, 13 of which contribute to the National Historic Landmark designation at Fort Monroe...

- Successful proposals will demonstrate how these buildings can be repurposed to fit seamlessly into the fabric of the vibrant, mixed-use community at Fort Monroe.

Fort Monroe advertised an adaptive reuse project for four particular sites in 2021

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Reimagine the Future of Fort Monroe (p.18)

The four sites identified in the adaptive reuse proposal included 11.5 acres of the 529 acres at Fort Monroe. Developers were asked to examine 13 historic buildings and one non-historic building, with a total of 300,000 square feet, and to select one, multiple, or all of the sites that were suited to their adaptive reuse capabilities.

Building 87 and Building 82 were included in the 2021 redevelopment proposal

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Reimagine the Future of Fort Monroe (p.44, p.88)

The entire 529 acres at Fort Monroe were included in the National Historic Landmark designation, but not all of the structures were considered to be historic. On the entire site, there were 166 contributing buildings and 90 non-contributing buildings where alterations would be more suitable.38

After receiving a grant from the National Park Service to restore Building 14, one of the oldest remaining residential structures, the historic preservation officer for the Fort Monroe Authority noted that the restoration of an 1880 building was foward-looking:39

- Preservation is more about looking to the future than looking to the past.

A $50 million redevelopment of the marina was planned to create "37 North at Fort Monroe," reflecting the site's location at 37° latitude. The project included replacing the Deadrise restaurant with two new restaurants and expanding the marina to accommodate superyachts. If 90 more parking spaces could be created, then a hotel would be incorporated in the new development.

Plans for the 37 North at Fort Monroe Project, with an improved Old Point Comfort Marina, restaurants, and hotel, were postponed in 2024. As a fallback, the Fort Monroe Authority renegotiated the long-term development agreement so Pack Brothers Hospitality would manage the marina.

Pack Brothers Hospitality said construction costs had increased from an estimated $50 million to $75 million:40

- What we have designed and had planned has become financially unattainable... I mean, somebody could build it; it's just not me; I don't have enough money to float it; it doesn't make money. And interest rates are higher, too.

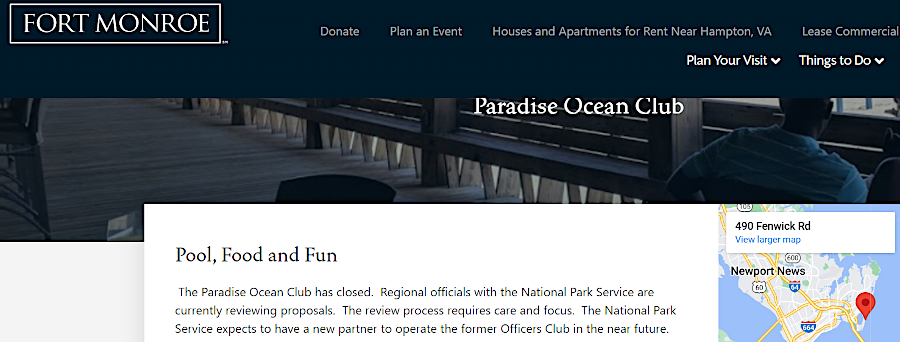

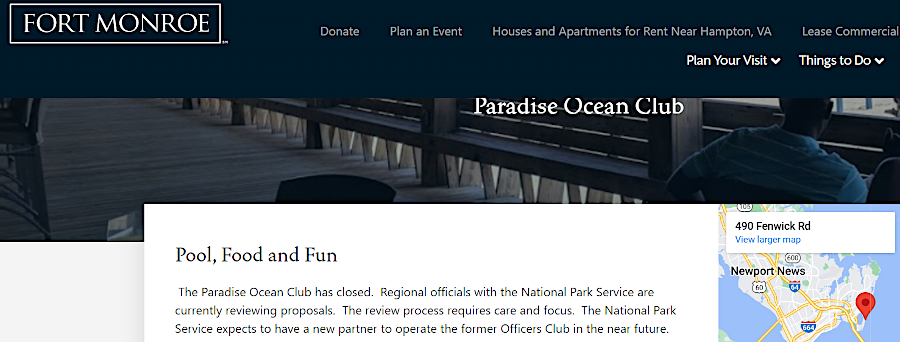

Paradise Ocean Club remained closed at the start of 2024

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Paradise Ocean Club

Other redevelopment planning also required revisions. The National Park Service leased the former Officers Club at Fort Monroe to the Paradise Ocean Club in 2012. After COVID-19, the popular beach club recovered successfully and attracted 2,000-3,000 people on weekends. Most customers were people of color.

After the 10-year lease expired in 2022, the Federal agency invited other bidders to rent the space. The Paradise Ocean Club sought to renew the lease, but discovered in early 2023 that the facility had deteriorated. It insisted the National Park Service remove mold and make other improvements or discount the rent, but negotiations failed and the space remained empty through the Summer.41

By 2024, Fort Monroe redevelopment had made progress but was still struggling. Half fof the buildings suitable for commercial use were leased, but the other half still needed to be rehabilitated.

The site was not generating jobs/revenue for the City of Hampton anywhere close to the economic benefit provided by the former military base. Proposals for new construction or rehabilitation of existing structures were constrained by the non-standard water and electrical systems built originally by the US Army. The Fort Monroe Authority lacked the $200 million required to standardize the utilities and attract new investment, though the FY25-26 budget proposed by Governor Youngkin did include $50 million to start the upgrade.

When asked in 2025 why redevelopment was slow, the Hampton City Manager cited the need to upgrade the non-standard utility infrastructure. That included the water and sewer services provided by HRSD:42

- When the Army was doing work there, they didn't have to follow some of the same regulations that local governments or other private sector companies would need to follow... For instance, they didn't have to do things the way Dominion Power would do them, or Virginia Natural Gas, or HRSD or anyone else...

- If you're a private sector developer, where are you going to go? You're going to go where it's easier to develop... Faster development means you're going to open faster, which means you're going to make money faster. What we call "virgin land development" is always easier than redevelopment.

Another major challenge was the requirement to assess the historical impacts of digging. The developer of the cancelled 37 North project said:43

- Every time we would excavate six inches into the ground, you have to have an archeologist on site. Well, guess what? Archeologists don't come and screen all your material for free.

Glen Oder navigated through many challenges for 12 years as the first Executive Director of the Fort Monroe Authority, and retired in 2024 after his 67th birthday. After a nationwide search, the Board of Directors of the Fort Monroe Authority hired Scott Martin and gave him the title of Chief Executive Officer. Referring to his predecessor, Martin said he would be "following a legend."44

Building 14 will be restored to its 1880's appearance

Source: Fort Monroe Authority, Fort Monroe at Old Point Comfort (Facebook post, November 15, 2022)

Links

References

1. "'Fast Track' Legislative Procedures Governing Congressional Consideration of a Defense Base Closure and Realignment (BRAC) Commission Report," Congressional Research Service, June 10, 2013, p.1, http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc463287/m1/1/high_res_d/R43102_2013Jun10.pdf (last checked December 26, 2014)

2. Base Closure and Realignment Report (Volume I, Part 1), Department of Defense, May 2005, p.C-26, http://www.defense.gov/brac/pdf/Vol_I_Part_1_DOD_BRAC.pdf (last checked December 26, 2014)

3. Base Closure and Realignment Report (Volume I, Part 2), Department of Defense, May 2005, p.Army-19, http://www.defense.gov/brac/pdf/Vol_I_Part_2_DOD_BRAC.pdf (last checked December 26, 2014)

4. "Fort Wool," National Register of Historic Places nomination form, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 1969, http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Cities/Hampton/114-0041_Fort_Wool_1969_Final_Nomination.pdf (last checked September 1, 2015)

5. "Final Environmental Impact Statement for BRAC 2005 Disposal and Reuse of Fort Monroe, Virginia," U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, May 2010, p.1-2, http://fmfada.velopers.net/pdf/FTMonroeFEIS.pdf; "Army, Fort Monroe Authority are at odds over 70 acres," Hampton Roads Business Journal, June 14, 2013, http://insidebiz.com/news/army-fort-monroe-authority-are-odds-over-70-acres (last checked December 24, 2014)

6. "Army, Fort Monroe Authority are at odds over 70 acres," Hampton Roads Business Journal, June 14, 2013, http://insidebiz.com/news/army-fort-monroe-authority-are-odds-over-70-acres; "Governor McDonnell Signs Fort Monroe Quitclaim Deed," Commonwealth of Virginia news release, June 6, 2013, http://www.fmauthority.com/governor-mcdonnell-signs-fort-monroe-quitclaim-deed/ (last checked December 23, 2014)

7. "Contractors Say The Hampton Base Is Prime For Redevelopment," Newport News Daily News, June 18, 2005, http://www.dailypress.com/news/dp-news-fortmonroe24-story.html (last checked December 26, 2014)

8. "Executive Director's Report," Fort Monroe Authority Board of Trustees Meeting, April 17, 2014, http://www.fmauthority.com/wp-content/uploads/Executive-Directors-Report-April-2014.pdf; "Meeting Minutes," Fort Monroe Federal Area Development Authority, December 14, 2007, http://www.fmauthority.com/wp-content/uploads/12-14-07minutes.pdf; "Meeting Minutes," Fort Monroe Federal Area Development Authority, November 19, 2009, http://www.fmauthority.com/wp-content/uploads/FMFADABoardMinutes11-19-09.pdf; "Fort Monroe Hampton, VA Reconnaissance Study," National Park Service, May 2008, p.52, p.55, http://www.fmauthority.com/wp-content/uploads/NPS_ReconStudy-5-08.pdf (last checked December 24, 2014)

9. "Fort Monroe Reuse Plan," Dover Kohl & Partners, 2008, http://doverkohl.com/files/pdf/Fort%20Monroe.pdf (last checked December 26, 2014)

10. "Foundation Document - Fort Monroe National Monument," National Park Service, July 2015, p.13, http://www.nps.gov/fomr/learn/management/upload/FOMR_FD_2015.pdf (last checked August 30, 2015)

11. "Fort Monroe Authority Act," Virginia Acts of Assembly - 2011 Session, http://4a6ccx32sq2y27cp8t4e1cz8.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/legislation.pdf (last checked August 30, 2015)

12. "On Fort Monroe: Sasaki vs. Dover, Kohl," Newport News Daily Press, October 31, 2013, http://articles.dailypress.com/2013-10-31/news/dp-tsq-hpt-notebook-1031-20131031_1_fort-monroe-authority-wherry-quarter-historic-buildings; "Section 2.2-2339.1. Fort Monroe Master Plan; approval by Governor," Code of Virginia, https://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?000+cod+2.2-2339.1; "Section 2.2-2340. Additional declaration of policy; powers of the Authority; penalty," Code of Virginia, https://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?000+cod+2.2-2340 (last checked December 24, 2014)

13. "Final Environmental Impact Statement for BRAC 2005 Disposal and Reuse of Fort Monroe, Virginia," U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, May 2010, p.ES-6, http://fmfada.velopers.net/pdf/FTMonroeFEIS.pdf (last checked December 24, 2014)

14. Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Colonial Williamsburg, Winter 2010, http://www.achp.gov/fort_monroe_final_story.pdf (last checked December 24, 2014)

15. "Establishment of the Fort Monroe National Monument," White House News Release, November 1, 2011, http://www.nps.gov/fomr/learn/management/upload/2011fortmonroe_prc

l.pdf; "Foundation Document - Fort Monroe National Monument," National Park Service, July 2015, p.7, http://www.nps.gov/fomr/learn/management/upload/FOMR_FD_2015.pdf (last checked August 30, 2015)

16. WebGIS Portal, City of Hampton, http://webgis.hampton.gov/sites/ParcelViewer/; "Final Environmental Impact Statement for BRAC 2005 Disposal and Reuse of Fort Monroe, Virginia," U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, May 2010, p.3-6, http://fmfada.velopers.net/pdf/FTMonroeFEIS.pdf (last checked December 24, 2014)

17. "Preserving the Wherry Quarter," The Virginian-Pilot, November 9, 2012, http://hamptonroads.com/2012/11/preserving-wherry-quarter (last checked December 24, 2014)

18. "Fort Monroe Historic Preservation Manual and Design Standards," Hanbury Evans Wright Vlattas + Company, August 2011, p.1A.3, http://www.fmauthority.com/wp-content/uploads/Design-Standards-Aug2011_Volume1_compressed.pdf; "Fort Monroe plan approved, now goes to governor," Daily News, October 24, 2013, http://articles.dailypress.com/2013-10-24/news/dp-nws-fort-monroe-plan-approval-20131025_1_master-plan-fort-monroe-authority-board-wherry-quarter(last checked August 30, 2015)

19. "Fort Monroe Master Plan 2013 Presentation to the Fort Monroe Board of Directors," Fort Monroe Authority, October 24, 2013, http://www.fmauthority.com/wp-content/uploads/Board_Master_Plan_Presentation_Final_2013-10-23.pdf (last checked December 26, 2014)

20. "Fort Monroe Authority OKs development plan," The Virginian-Pilot, October 25, 2013, http://hamptonroads.com/2013/10/fort-monroe-authority-oks-development-plan; "Preservation Groups Outline Joint Vision for the Future of Fort Monroe," news release regarding joint letter to Virginia Secretary of Natural Resources, April 28, 2008, Civil War Preservation Trust, http://www.civilwar.org/aboutus/news/news-releases/2008-news/preservation-groups-outline.html (last checked December 24, 2014)

21. Letter to Chairman, Fort Monroe Authority Board of Trustees, National Trust for Historic Preservation, October 23, 2013, http://www.preservationnation.org/assets/pdfs/saving-places/FM_Fort-Monroe-NTHP-to-FMA-10-24-13.pdf (last checked December 24, 2014)

22. "Foundation Document - Fort Monroe National Monument," National Park Service, July 2015, p.13, http://www.nps.gov/fomr/learn/management/upload/FOMR_FD_2015.pdf (last checked August 30, 2015)

23. "Gov. Terry McAuliffe wants to expand Fort Monroe monument area," Newport News Daily Press, November 6, 2014, http://www.dailypress.com/news/hampton/dp-nws-mcauliffe-fort-monroe-park-connector-20141106-story.html; "Protecting the fort," letter to the editor, National Parks Conservation Association, Newport News Daily Press, November 16, 2014,http://www.dailypress.com/news/opinion/letters/dp-edt-nws-letsmon-1117-20141116-story.html (last checked December 26, 2014)

24. "For future generations," Newport News Daily Press, December 20, 2014, http://www.dailypress.com/news/opinion/editorials/dp-edt-fort-monroe-plan-editorial-20141221-20141220-story.html (last checked December 26, 2014)

25. "Fort Monroe Master Plan 2013 Presentation to the Fort Monroe Board of Directors," Fort Monroe Authority, October 24, 2013, http://www.fmauthority.com/wp-content/uploads/Board_Master_Plan_Presentation_Final_2013-10-23.pdf (last checked December 26, 2014)

26. "Tangled web of dollars ties Virginia localities back to state," Newport News Daily Press, April 21, 2015, http://www.dailypress.com/news/politics/dp-nws-local-budgets-state-aid-20150421-story.html; "Fort Monroe cost to Hampton not being paid," Newport News Daily Press, April 21, 2015, http://www.dailypress.com/news/hampton/dp-nws-hpt-notebook-0422-20150421-story.html (last checked April 22, 2015)

27. "Gov. McAuliffe signs deed transferring Fort Monroe land to Park Service," The Virginian-Pilot, August 26, 2015, http://hamptonroads.com/2015/08/gov-mcauliffe-signs-deed-transferring-fort-monroe-land-park-service; "National Park Service to receive portions of Fort Monroe," Daily Press, August 20, 2015, http://www.dailypress.com/news/hampton/dp-nws-fort-monroe-monument-progress-20150820-story.html; "Notes and Notables: Flip-flops, Fort Monroe and HU's Marching Force," Daily Press, May 2, 2019, https://www.dailypress.com/news/opinion/editorials/dp-edt-notes-notables-0503-story.htm; "Last bit of Army land on Fort Monroe — under The Chamberlin — goes to the state," The Virginian-Pilot, December 9, 2021, https://www.dailypress.com/government/virginia/dp-nw-chamberlin-20211209-2e23mtvtvnbbbjek2a3qjgscna-story.html (last checked December 17, 2021)

28. "Jefferson Davis's name is gone from memorial at site where first Africans arrived," Washington Post, August 6, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/anathema-jefferson-daviss-name-is-gone-from-memorial-at-place-where-first-africans-arrived/2019/08/06/496536ce-b85d-11e9-bad6-609f75bfd97f_story.html (last checked August 8, 2019)

29. "Surprise Fort Monroe language in more-than $100 billion Va. Budget," Daily Press, March 10, 2016, http://www.dailypress.com/news/politics/dp-nws-ga-budget-20160310-story.html (last checked March 18, 2016)

30. "Fort Monroe board approves more land for National Parks Service," Daily Press, March 17, 2016, http://www.dailypress.com/news/hampton/dp-nws-hampton-fort-monroe-retreat-20160317-story.html (last checked March 18, 2016)

31. "Senators Aim to Transfer Coastland to Fort Monroe," Daily Press, July 31, 2019, https://www.dailypress.com/news/hampton/dp-nws-fort-monroe-nps-transfer20190730-story.html (last checked July 31, 2019)

32. "Fort Monroe is better protected in the state's hands, for now," Daily Press, August 3, 2019, https://www.dailypress.com/opinion/dp-edt-fort-monroe-nps-transfer-0804-story.html (last checked August 4, 2019)

33. "The Scope of the Challenge," Fort Monroe Authority, April 19, 2017, https://fortmonroe.org/wp-content/uploads/5.-The-Scope-of-the-Challenge.pdf (last checked November 22, 2019)

34. "Fort Monroe votes to transfer 35 acres of coastal land to National Park Service," Daily Press, November 21, 2019, https://www.dailypress.com/government/virginia/dp-nw-fort-monroe-trustee-wherry-20191121-6htalqz2brgchmcfbahavtaexa-story.html; "35 Acre Support Resolutions," Fort Monroe Authority, November 21, 2019, https://fmfada.egnyte.com/fl/amtQFY19kT/#folder-link/ (last checked November 22, 2019)

35. "Virginia lawmakers urge Department of the Interior to accept commonwealth's donation of 40 acres on Fort Monroe," WAVY, September 16, 2021, https://www.wavy.com/news/local-news/hampton/virginia-lawmakers-urge-department-of-the-interior-to-accept-commonwealths-donation-of-40-acres-on-fort-monroe/

36. "Governor Northam Announces Redevelopment Plans for Fort Monroe Authority," Governor of Virginia news release, May 19, 2021, https://www.governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/all-releases/2021/may/headline-895415-en.html; "Regulators give 'governmental activity' exemption to marina and hotel project at Fort Monroe," Virginia Mercury, October 27, 2021, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2021/10/27/marine-resources-commission-exempts-fort-monroe-redevelopment-from-wetlands-beach-permitting/ (last checked October 27, 2021)

37. "Reimagine the Future of Fort Monroe," Fort Monroe Authority, 2021, p.2, https://reimagine.fortmonroe.org/wp-content/uploads/rfrep.pdf (last checked December 2, 2021)

38. "Reimagine the Future of Fort Monroe," Fort Monroe Authority, 2021, p.4, https://reimagine.fortmonroe.org/wp-content/uploads/rfrep.pdf (last checked December 2, 2021)

39. "After surviving lightning strike, hurricane and termites, historic officer's quarters on Fort Monroe to be preserved," WHRO, November 28, 2022, https://whro.org/news/34096-after-surviving-lightning-strike-hurricane-and-termites-historic-officer-s-quarters-on-fort-monroe-to-be-preserved (last checked November 29, 2022)

40. "Old Point Comfort marina getting hotel, restaurant as Fort Monroe announces $40M overhaul," The Virginian-Pilot, May 19, 2021, https://www.pilotonline.com/2021/05/19/old-point-comfort-marina-getting-hotel-restaurant-as-fort-monroe-announces-40m-overhaul/; "Fort Monroe gets ready for face-lift," The Virginian-Pilot, July 24, 2023, https://digitaledition.pilotonline.com/html5/desktop/production/default.aspx?pubid=248c93c1-2d54-411c-a446-54c2127375d1&edid=95f0579e-3f3d-4b42-99df-372015e30b90; "Fort Monroe marina redevelopment paused indefinitely due to rising costs, developer says," The Virginian-Pilot, January 17, 2024, https://www.pilotonline.com/2024/01/17/fort-monroe-marina-redevelopment-paused-indefinitely-due-to-rising-costs-developer-says/ (last checked January 18, 2024)

41. "Beach club dispute still simmering," The Virginian-Pilot, August 9, 2023, https://www.pilotonline.com/2023/08/09/paradise-ocean-club-owner-accuses-national-park-service-of-trying-to-sabotage-lease-negotiations/ (last checked August 12, 2023)

42. "Hampton hopes to redevelop Fort Monroe into a landmark. Years of stagnation has slowed it," The Virginian-Pilot, May 1, 2025, https://www.pilotonline.com/2025/04/30/fort-monroe-development/ (last checked May 1, 2025)

43. "State-run Fort Monroe balances lingering development woes with the history at its core," WHRO, February 20, 2024, https://whro.org/news/45070-fort-monroe (last checked February 22, 2024)

44. "Glenn Oder, executive director of Fort Monroe Authority, to retire this year," The Virginian-Pilot,

April 3, 2024, https://www.pilotonline.com/2024/03/29/glenn-oder-executive-director-of-fort-monroe-authority-to-retire-this-year/; "'Following a legend,' Martin to take helm," The Virginian-Pilot, November 23, 2024, https://digitaledition.pilotonline.com/html5/desktop/production/default.aspx?pubid=248c93c1-2d54-411c-a446-54c2127375d1&edid=030f45e3-fe5e-431d-b845-53d41bbda351 (last checked November 23, 2024)

the Trump Administration declined the donation of land (red polygon) to connect two sections of Fort Monroe National Monument

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Military in Virginia

Virginia Places