batteries at Fort Hunt after World War I were expected to fire together with batteries at Fort Washington to block enemy ships from moving up the Potomac River

Source: National Park Service, Fort Hunt

batteries at Fort Hunt after World War I were expected to fire together with batteries at Fort Washington to block enemy ships from moving up the Potomac River

Source: National Park Service, Fort Hunt

The National Park Service succinctly summarizes how Fort Hunt has changed over the years:1

Human history of the site starts long before George Washington. When John Smith sailed up the Potomac river, he found the area occupied by various tribes allied under the Conoy/Piscataway paramount chiefdom. Smith encountered the Tauxenents concentrated at what is now Mason Neck. The Piscataway were living where Piscataway Creek met the Potomac River, across from Fort Hunt.

Giles Brent was the first colonist to patent the land where Fort Hunt is located. Brent had married Kittamaquund, the daughter of the chief of the Piscataways, acquiring a claim to much of Maryland. Lord Calvert would not support that claim, so Brent moved to Virginia. In 1653-54 he patented 1,800 acres along the Potomac River, including Fort Hunt. Technically, Giles Brent II (Brent's two-year old son) was the first colonial owner. George Washington purchased the property from Brent's heirs in 1760 and River Farm became part of his slave-based plantation operations.2

George Washington acquired the site of Fort Hunt in 1760 and managed it as part of his "River Farm"

Source: Library of Congress, A map of General Washington's farm of Mount Vernon from a drawing transmitted by the General

In 1892 the Washington, Alexandria, & Mt. Vernon Electric Railway was completed between Alexandria and Mount Vernon. The easy transportation into the city started to spur residential development, but by then the War Department had already decided that a new fort on the Virginia side of the Potomac River was needed to protect Washington, DC from a naval attack.

Fort Washington on the Maryland shoreline had failed to block the British navy from sailing up the Potomac River in the War of 1812 and looting Alexandria. In 1886 the Board on Fortifications or Other Defenses (known as the Endicott Board, after Secretary of War William C. Endicott) identified where to build a fort in Virginia that could partner with Fort Washington to control the Potomac River shipping channel. Eight Endicott batteries with breech-loading, disappearing guns were added at Fort Washington, while four batteries were built at a new facility across the Potomac River at Sheridan Point.

The Federal government started to purchase land at Sheridan Point in 1893. Acquiring a total of 197 acres from separate landowners required land condemnation for some purchases, so a judge could determine fair market value. The last court case was finally resolved in 1906.

In 1899, President William McKinley named the site after Brevet Major General Henry Jackson Hunt. Hunt had ended his military career as governor of the Soldiers' Home in Washington, DC.3

Fort Hunt was part of the Endicott fortifications. The War Department constructed four concrete batteries with Endicott guns, plus housing for officers and enlisted men and some 30 substantive support structures. Today the support structures are gone. The clearest evidence of the fort's purpose in the Spanish-American War are the deteriorated and overgrown concrete batteries.

In theory, guns from both Fort Washington and Fort Hunt together could control the shipping lane in the Potomac River and protect the national capital. The theory was never tested; the Spanish Navy never entered the Chesapeake Bay, so the capabilities of Fort Hunt were not tested. The last of the guns was installed by 1904.

During World War I, U-boats were recognized as the greatest German Navy threat. The coastal artillery at Fort Hunt might still have some value, but not far inland on the shoreline of the Potomac River. The large caliber guns were moved to Europe and placed on railway cars.

After the end of World War I, the US Congress reduced the size of the military. After a brief time when it hosted the Finance School of the US Army, Fort Hunt was declared to be surplus on April 5, 1924. Defense of the Potomac River shifted to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, with new coast defenses established at Cape Henry.

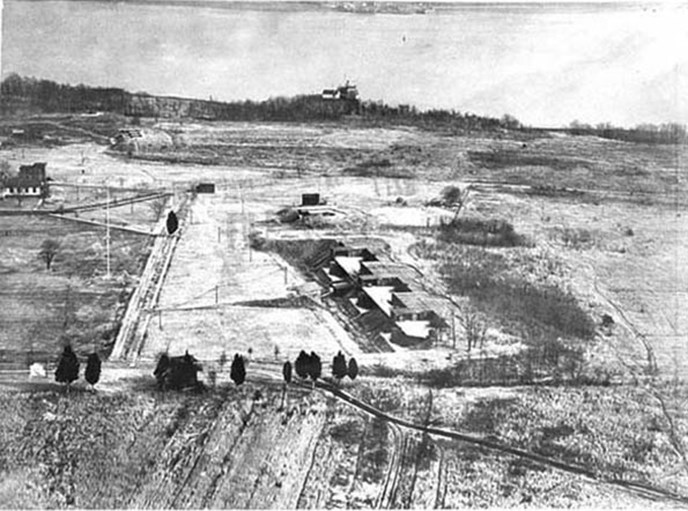

Fort Hunt in 1923, with abandoned structures and gun emplacements at Battery Mount Vernon

Source: National Park Service, "'By the River Potomac": An Historic Resource Study of Fort Hunt Park, George Washington Memorial Parkway, Mount Vernon, Virginia (Figure 20, Figure 13)

The War Department retained control of the abandoned fort and buildings in case Fort Hunt might be occupied by the D.C. National Guard. That never happened, but the 16th Infantry Brigade was relocated there between 1928-1931. An African American ROTC unit trained there in 1931, as arrangements were made to transfer Fort Hunt to the National Park Service. The ROTC unit was given temporary, separate quarters for its use.

Before the land transfer Fort Hunt was used as a camp for Bonus Marchers, veterans from World War I who were demanding immediate payment of a bonus that was not scheduled until 1945. The War Department built a temporary 300-bed hospital at Fort Hunt for the Bonus March "army," along with a tent camp. After the US Senate rejected the demand for immediate payment of the bonus, the veterans were evicted from temporary camps and by mid-August 1932 Fort Hunt was empty again.

During a second Bonus March in 1933, the War Department bused the demonstrators to Fort Hunt - away from downtown Washington, DC - and provided food and housing there. Eleanor Roosevelt visited the marchers there on May 16, 1933. Most of the marchers ended up joining the Civilian Conservation Corps, dispersing to various camps and leaving Fort Hunt empty again.

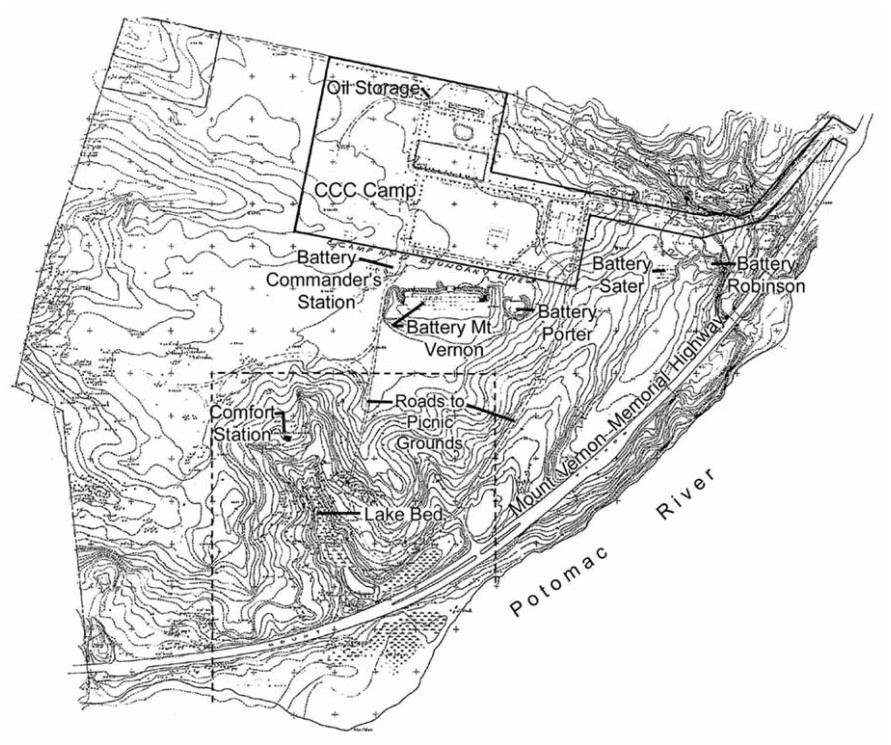

World War I veterans who composed the Bonus March army were housed temporarily at Fort Hunt in 1932, until being evicted in August

Source: National Park Service, Fort Hunt Cultural Landscapes Inventory (p.42)

In 1930, the US Congress had agreed that Fort Hunt was no longer useful as a military installation and the site should become a recreational component of the new George Washington Memorial Parkway. The land transfer to the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital occurred on August 28, 1932, after eviction of the Bonus Marchers. Soon afterwards, the National Park Service absorbed the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital.

Between 1893-1932, the only casualty in the line of duty occurred when a private on guard duty accidentally shot himself:4

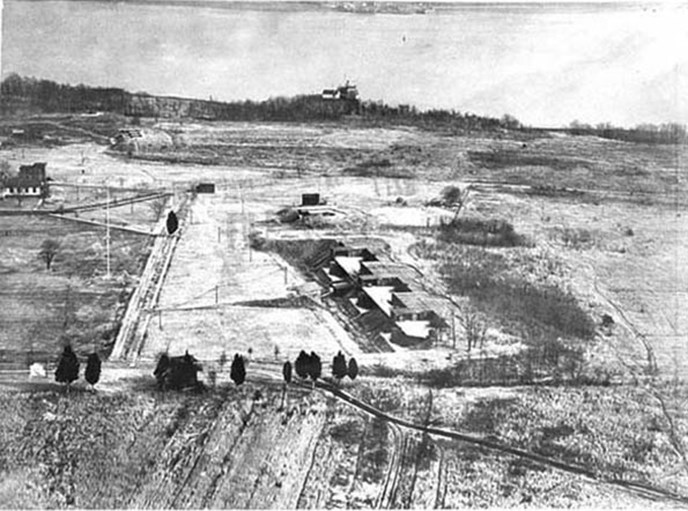

in 1937, a baseball field was located north of the Spanish-American War batteries (circled)

Source: Fairfax County, Historical Imagery Viewer

In October 1933, Fort Hunt became the site of a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp designated as NP-6. Camp capacity was 200 enrollees. The enrollees built wooden barracks, mess halls, administrative and recreational buildings that were wired for electricity and heated by coal stoves. Away from the camp, they performed maintenance and landscaping at various National Park Service sites around the national capital.

When the King and Queen of Great Britain visited Mount Vernon in 1939, they toured the Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Fort Hunt. The king was especially through, asking enrolleees many questions regarding their living conditions, pay, and work. Eleanor Roosevelt noted that he was comparing the camp with the British way of providing welfare to out-of-work coal miners. Great Britain did not have an equivalent program to encourage children of the miners to work in exchange for government support.5

a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp operated at Fort Hunt during the 1930's

Source: National Park Service, Fort Hunt - Cultural Landscapes Inventory

When the third Bonus March reached Washington in 1934, the Civilian Conservation Corps were moved out. Fort Hunt's structures and tents provided housing and food again. As in 1933, the Roosevelt Administration convinced most of the marchers in 1934 to join the Civilian Conservation Corps and end their protest.6

At the start of World War II, Fort Hunt was transferred back to the War Department, but not revamped to serve as a defensive facility barring enemy warships from sailing up the Potomac River. Fort Hunt was used during the war as a secret interrogation facility for 3,451 prisoners of war, including German Navy commanders and crew. The West Coast interrogation facility counterpart was at Byron Hot Springs, California. Both sites were classified as "Temporary Detention Centers" rather than as Prisoner of War (POW) camps, so the Geneva conventions allowing visitation could be circumvented.

Fort Hunt was selected after the War Department considered 26 sites within 100 miles of Washington, DC where facilties were already available to interrogate prisoners of war. Swannanoa near Charlottesville was considered, but it was 127 miles from Washington, privately owned, and required more alteraton of existing structures.

The military was granted full use of the site by the Secretary of the Interior except for the historic gun batteries. The National Archives had already been authorized to use four of them for storage of nitrate film stock, which had been judged to be too great of a fire hazard to remain in downtown Washington during wartime. After the end of World War II, the audiovisual records were moved to warehouses in Maryland. After 2007, the nitrate film came back to Virginia for storage and preservation at the Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation of the Library of Congress, located at Mount Pony in Culpeper County.

Secretary Harold Ickes authorized use of Fort Hunt on May 15, 1942. By July 30, all preparations were completed for accepting the first prisoners. The first ones arrived in August, and were placed inside Enclosure A.

Intelligence gathered at Fort Hunt revealed that V-1 and V-2 rockets were produced at Peenemunde, and more-intense bombing raids on that site followed.

After the end of Would War II, some German scientists were debriefed at Fort Hunt. Interrogators with experience at Fort Hunt also debriefed rocket scientist Wernher von Braun and key members of his scientific team when they were brought to Boston in 1945.

To obscure the intelligence gathering activities, the military referred to Fort Hunt during World War II as just "PO Box 1142." During the war:7

The escape and evasion training was especially important to the Eighth Army Air Force. Its daylight bombing raids over Europe led to many downed aircraft. The E&E program, headquartered at what is now Pavilion A in Fort Hunt Park, arranged for radios, maps, currency and compasses to be smuggled into German prisoner of war camps to facilitate escapes. By the end of World War II, 95,532 Americans had ben captured; 737 managed to escape and return to Allied lines.

The military intelligence program at PO Box 1142 compiled information from multiple sources, including interrogated prisoners and captured documents, to identify the locations and strengths of German troops in Europe.8

Prisoners thought to be worth special interrogation were first brought to a camp at Pine Grove Furnace, Pennsylvania. The selection process to determine which people to take in windowless buses to PO Box 1142 got more sophisticated throughout the war. By 1944, detainees were kept at PO Box 1142 for only a week and then sent on to a permanent prisoner of war camp.

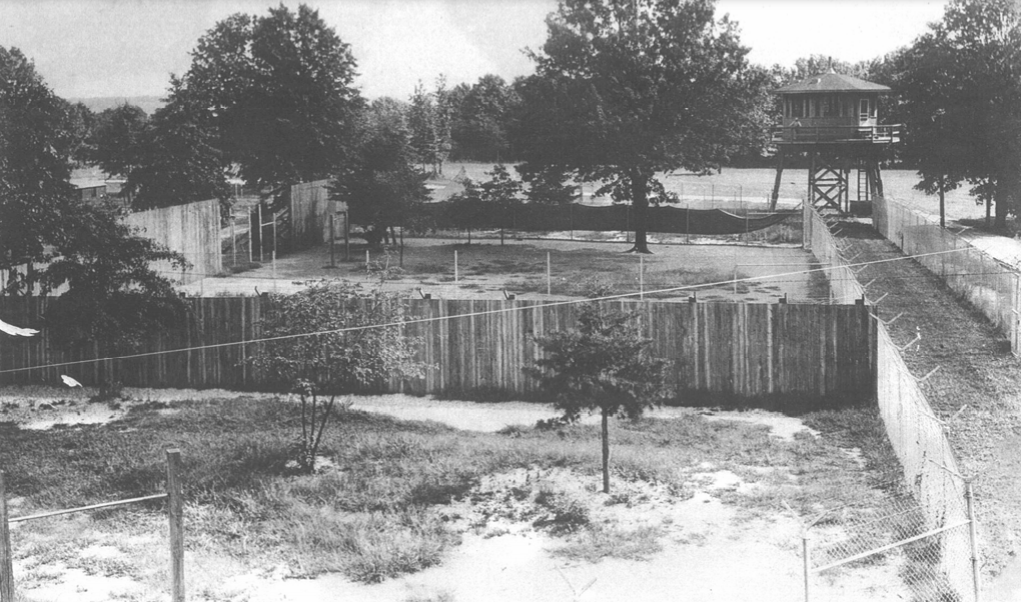

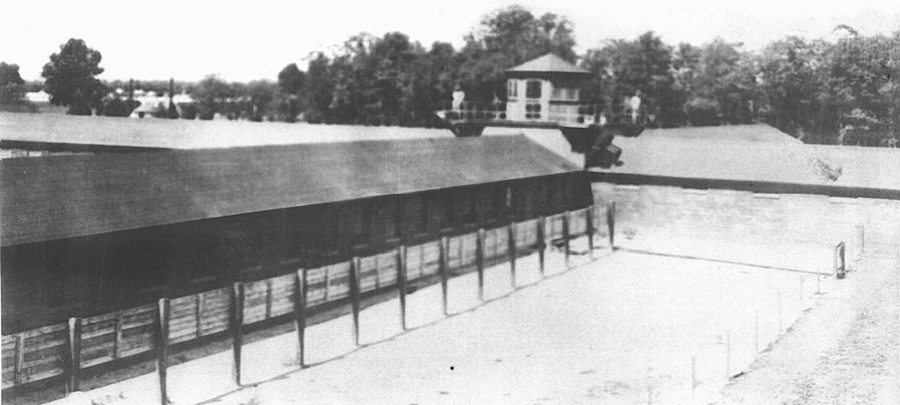

New buildings were added to supplement those remaining at Fort Hunt from the time of the Spanish-American War and the Civilian Conservation Corps period. Enclosure A was built by August 1942 to house prisoners and interrogation rooms, together with structures needed for guards and supplies. Enclosure B was added in April 1944, with additional security. There were four guard towers outside the two "cyclone" wire fences, which were 15 feet apart and had barbed wire on the top.

Time for exercise was built into the schedule after one detainee complained to Swiss monitoring authorities. The only known escape attempt occurred on June 15, 1944. The captured commander of the U-515 was desperate. He had been told he would be handed over to the British and treated as a war criminal, charged with machine-gunning in the water some survivors of a ship the U-boat had sunk. The commander got over the 10-foot high wire fence of the exercise yard, but was killed by rifle fire from a guard tower as he climbed the second fence.

Interrogation techniques varied, ranging from establishing personal connections (even offering liquor and cigarettes) through intimidation and confrontation. Microphones were hidden in rooms with hopes of learning from unguarded conversations, though many prisoners recognized that they could not have "private" conversations indoors.

Two separate interrogators later described how they extracted information of military value:9

One interrogation technique was to encourage German soldiers to help end the way quicker, and thus minimize destruction of cities. In 2007, an interrogator described his approach:10

in 1944, a U-Boat commander was killed while trying to escape from Enclosure A

Source: National Park Service, "'By the River Potomac": An Historic Resource Study of Fort Hunt Park, George Washington Memorial Parkway, Mount Vernon, Virginia (Figure 31)

Enclosure B, completed in 1944, had a central guard tower and other security measures learned from experience with Enclosure A

Source: National Park Service, "'By the River Potomac": An Historic Resource Study of Fort Hunt Park, George Washington Memorial Parkway, Mount Vernon, Virginia (Figure 32)

The War Department's authorization to use Fort Hunt was supposed to end a year after the war, but the National Park Service did not regain custody of the site until January 1948. The intelligence-gathering operations moved to Mitchell Field in New York, and by the end of November 1946 the only remaining military personnel were responsible for site security and removing the temporary buildings.

Fort Hunt was returned to the National Park Service in 1948 and became a 190-acre unit within the George Washington Memorial Parkway. Not until the 1990's was the secret history revealed of its use in World War II.11

after World War II, Fort Hunt became a public recreation site managed by the National Park Service again

Source: Library of Congress, George Washington Memorial Parkway, Along Potomac River from McLean to Mount Vernon, VA, Mount Vernon, Fairfax County, VA

The recreational opportunities at Fort Hunt were coveted by the Commonwealth of Virginia. State official desired to establish a new state park in Northern Virginia, but in 1953 the National Park Service sent a clear message that the Federal agency would not relinquish the land. Fort Hunt was already being used heavily by Boy/Girl Scout troops and by local organizations to host picnics and other gatherings, and the ballfields were in constant use.

The construction of a new picnic pavilion and comfort station in the 1960's enhanced the recreational opportunities. At the time, no archeological study was done. The new pavilion ended up essentially on top of the old post hospital known as the "Creamery" during World War II, where the escape and evasion (E&E) program had been centered. Almost all records of that program had been destroyed after the surrender of Germany, so it is the least-documented major component of the history of Fort Hunt.12

Fort Hunt was once owned by George Washington

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online