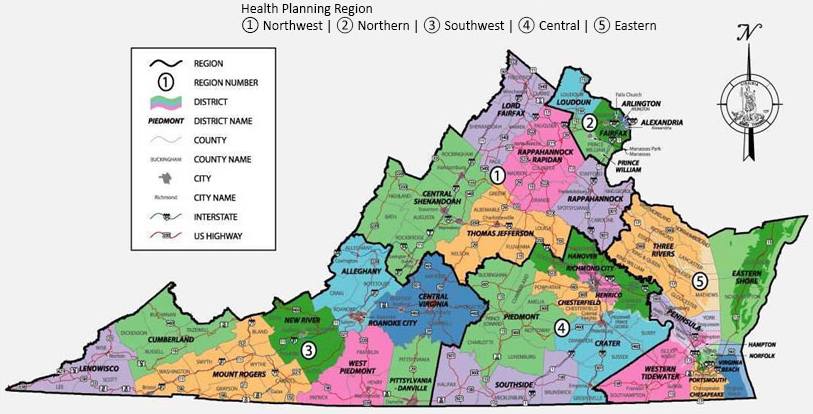

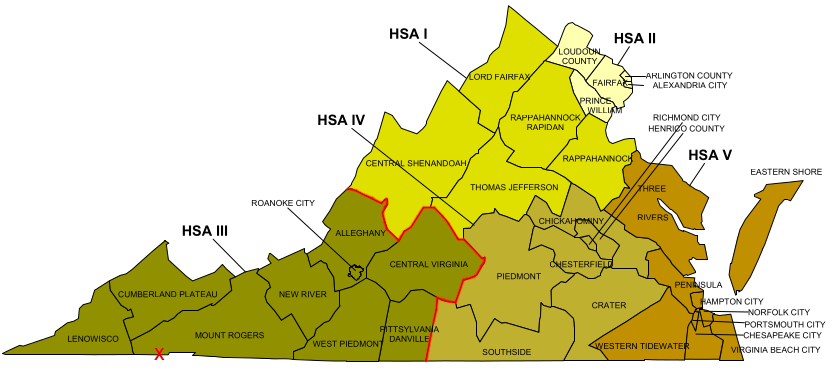

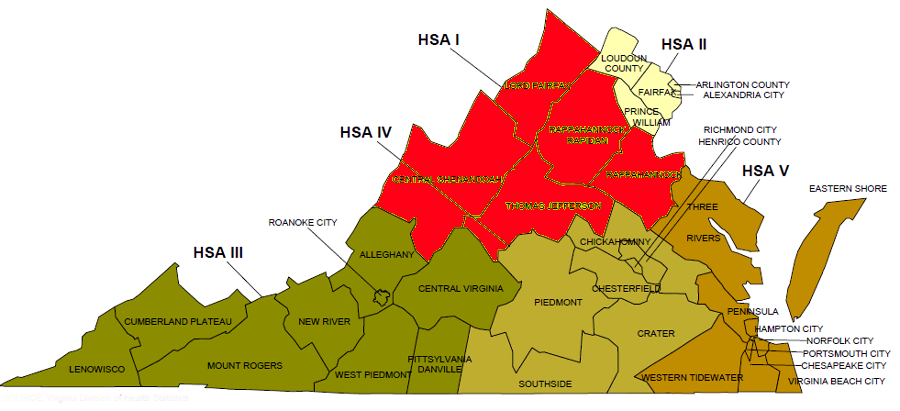

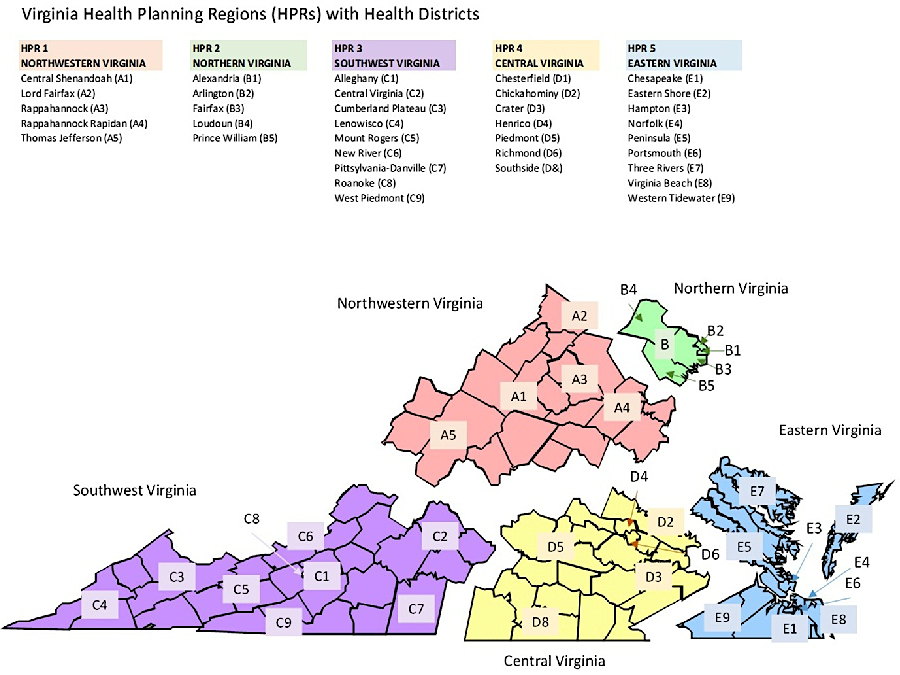

health district boundaries were used to allocate licenses for Virginia's first five medical marijuana dispensaries in 2018

Source: Virginia Department of Health, Map of Virginia by Health Planning Regions

health district boundaries were used to allocate licenses for Virginia's first five medical marijuana dispensaries in 2018

Source: Virginia Department of Health, Map of Virginia by Health Planning Regions

The Virginia General Assembly started the process towards legalizing the use of marijuana in 1979. The General Assembly blocked prosecution for possession of marijuana if a doctor had prescribed it to a patient for the treatment of cancer or glaucoma.

Marijuana provided uniquely-effective relief for some patients suffering from the side effects of chemotherapy and other treatments, or pain from some diseases. For glaucoma patients, it lowered eye pressure.

The law did not create a legal process for patients to obtain marijuana for their medical use.

In 1997, Virginia legislators considered repealing the law. In the end the General Assembly retained the protection of cancer and glaucoma patients. The Federal government continued to list marijuana on Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act; Virginia's law had no impact on Federal restrictions.1

The 1979 law required doctors to write a prescription for use of marijuana. Because doctors can legally "prescribe" only products certified by the Food and Drug Administration, legally they can only "recommend" use of marijuana. A state law that authorized prescriptions would violate the Federal Controlled Substances Act.

That conundrum was solved in 2002. A Federal circuit court ruled that doctor "recommendations" are a form of speech protected by the First Amendment.2

The Virginia General Assembly relaxed the requirement for a prescription in 2015, by authorizing possession based on a doctor's "recommendation." The legislature also prohibited prosecution of patients with intractable epilepsy who possessed cannabidiol, if they could show they had a doctor's certificate for treatment with the oils.

Cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol acid (THC-A) oil are chemical compounds extracted from the hemp plant that do not create a psychoactive response or marijuana "high." Numerous health benefits are claimed for using the oils, primarily applied to the skin.

Federal drug officials were opposed to legalizing the oils, because THC-A exposed to heat can convert to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The ultimate compound creates an intoxicating effect, creating an equivalent for recreational marijuana.

Similar to the 1979 legislation, the 2015 law technically created an affirmative defense for a narrow group of people who possessed marijuana oils based on a doctor's decision. The 2015 law also provided protection from prosecution for caretakers and parents/legal guardians, since they too could be found in possession.

The 1979 or the 2015 laws did not legalize possession of other marijuana products besides cannabidiol (CBD) oil and tetrahydrocannabinol acid (THC-A) oil. Possession of buds from flowers, or other parts of marijuana plants, remained illegal. No Virginia law has ever allowed for any recreational use of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

Virginia Tech research supported growth of industrial hemp, but not marijuana used for psychoactive impacts

Source: Virginia Tech, Facts About Industrial Hemps

Most significantly, the laws provided no legal mechanism for patients to acquire any form of marijuana for medical purposes. No one within Virginia was authorized to grow marijuana for medical use, and no one was authorized to import it from outside the state.

Patients were expected to acquire marijuana through means that were still illegal. The "affirmative defense" meant that selected people could not be prosecuted for breaking the law prohibiting possession, if a doctor had certified the cannabidiol was being used for treatment of glaucoma, cancer, or epilepsy. Nonetheless, possession was still technically illegal under state law.

Federal law enforcement agents were not constrained by the state law blocking prosecution. Federal officials focused on large-scale syndicates transporting drugs rather than punishment of individual users, and Federal rules began to shift in 2014.

In that year, the Federal government authorized researchers to grow "industrial hemp," which required that the tetrahydrocannabinol concentration could not exceed 0.3 percent. Four years later, the law was altered so states could license all farmers to grow industrial hemp. The possession of marijuana plant material exceeding 0.3 percent remained illegal under Federal law.

Farmers seeking to grow hemp/marijuana discovered that the seed they bought had reliable characteristics for growing fiber, but might generate unexpected and undesired levels of cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). There had been too little time to plant different strains and ensure consistent genetics for Cannabis sativa grown for its health and psychoactive effects.

Seed certification had not been a standard business practice when growing marijuana was illegal. One agricultural specialist noted:3

In 2016, the General Assembly began to broaden the number of people who would be protected from state prosecution. The legislature authorized the Virginia Board of Pharmacy to prepare to license pharmaceutical processors who could grow marijuana for medical purposes, with tetrahydrocannabinol concentrations that exceeded the 0.3 percent limit for industrial hemp.

In 2018, the legislature broadened its authorization to use medical marijuana for any condition, not just cancer, glaucoma, or epilepsy. Legislators noted that medical marijuana would be a better alternative than opiates. Recreational use of any form of marijuana was not authorized by the 2018 Virginia law.

marijuana oil producers quickly advertised legalization in Virginia

Source: ZenPipe

The legal version had to contain at least 15% tetrahydrocannabinol acid (THC-A), but not more than 5% of the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) that produces euphoria. Marijuana sold for recreational use has around 30% THC.4

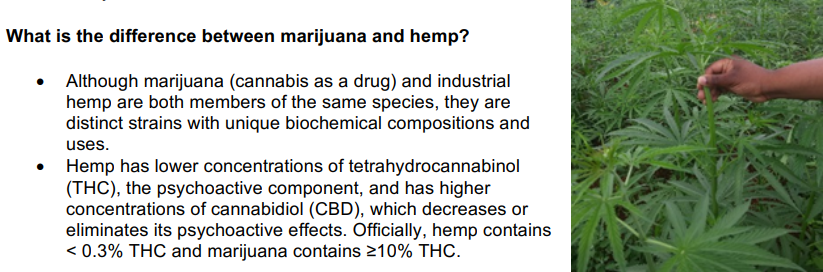

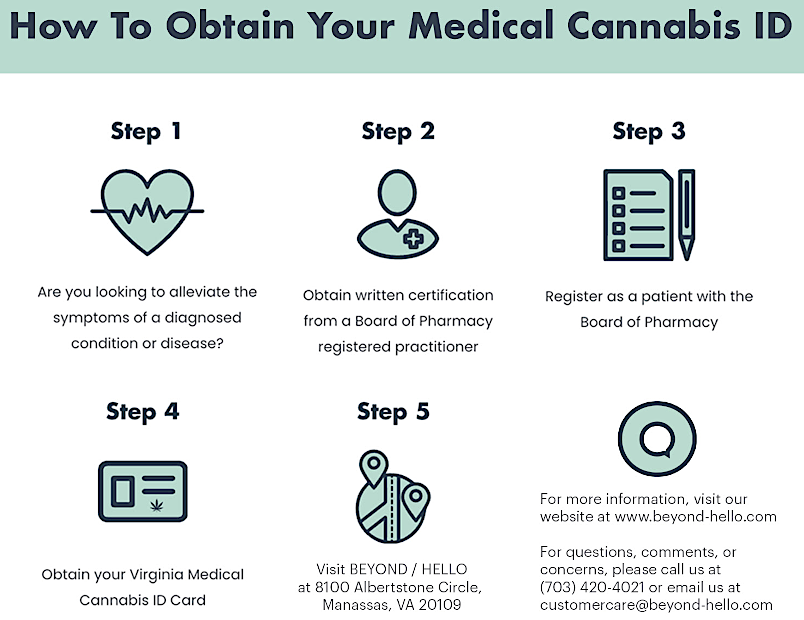

The 2018 law finally established workable procedures for distribution of medical marijuana. Patients were required to get a physician's recommendation, then register with the Virginia Board of Pharmacy. Physicians had to be registered as well.

Patients who did not register and get a recommendation from a registered physician could no longer claim the affirmative defense that was established under the 1979 and 2015 laws. Registration fees were set at $50/year.5

at the end of 2018, there were 214 physicians registered for "recommending" CBD/THC-A oils

Source: Virginia Department of Health Professions, License Lookup

The law also authorized the Board of Pharmacy to license pharmaceutical processors who could:6

cultivating medical marijuana became legal in Virginia in 2018

Source: Pixabay

The state invited companies to bid for the right to produce medical marijuana products and operate dispensaries. The Request for Applications included criteria for awarding up to 275 points when evaluating applications. The most significant ranking factor, the only one worth up to 50 points, was "Agriculture, Production, and Dispensing Expertise."

The Board of Pharmacy promised to issue one permit in each of the state's five heath regions. Competition was intense from companies both within and outside of Virginia. In the end, 32 companies submitted a total of 51 applications. Hampton Roads generated the greatest interest; there were 15 applications for the one permit to be issued for that region. One proposal identified that the horticultural part of its operation would be based on growing 5,000 marijuana plants adjacent to NASA Langley Research Center.

They paid $10,000 per application, and hoped they would become one of the five companies awarded permits. The initial fee of $60,000/year for each of the five pharmaceutical processor permittees was a minor part of their business plans. One applicant predicted it would spend $10-$20 million to start up the business. The medical marijuana market alone might not justify such expenses, but businesses anticipated that getting in on the ground floor would position them for greater profits once recreational use was legalized.7

The state required that the five pharmaceutical processors must grow, process, and sell the marijuana at just one location. No other state had such a requirement for complete vertical integration mandating that the companies with licenses had to find or construct production/processing/sales buildings. In a state with eight million residents, there would be only five sales outlets.

Makers of cigarettes/cigars/pipe tobacco products and liquor distilleries are allowed to grow, process, and retail at separate locations. Wineries which make direct sales to customers at tasting rooms receive some benefits if they grow their grapes in Virginia, but no agricultural businesses faced more restrictions than medical marijuana processors.

The Virginia Board of Pharmacy mandated implementation of electronic radio-frequency identification (RFID) seed-to-sale systems that could track the cannabis from either the seed or immature plant stage until the cannabidiol oil and THC-A oil was sold to a customer, and even prohibited production facility employees from wearing clothing with a pocket.

Initial regulations also prohibited advertising other than listing basic information on a website about a processor's location, hours of operation, and laboratory results. No window shopping was allowed; only employees, laboratory personnel, and registered patients (or parents/legal guardians) were allowed on the premises of a processor.

A pharmacist-in-charge (PIC) always had to be present. That person had ultimate responsibility for distribution, reflecting Virginia's perspective that medical marijuana was dispensed as a drug:8

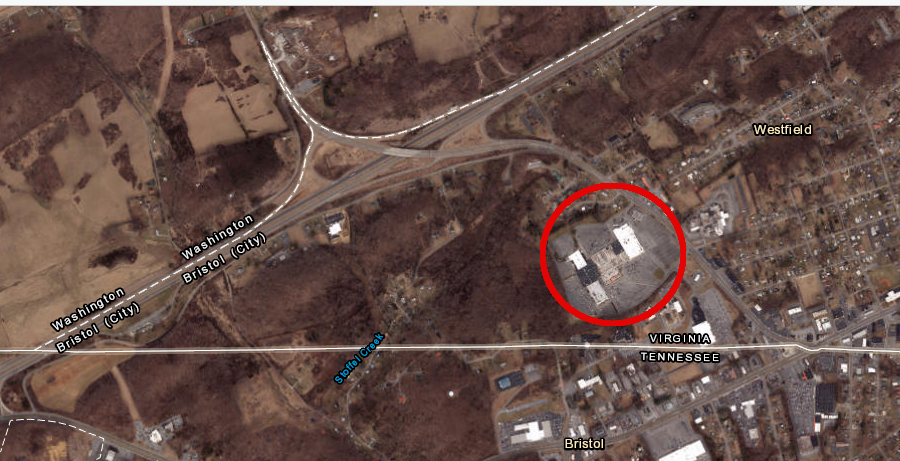

Ten companies competed for the permit in the Third Health District, which stretches from Lynchburg and Danville west to Cumberland Gap. Dharma Pharmaceuticals won the permit, and based its operations in the vacant JC Penny's store at the old Bristol Mall. One of the investors in the pharmaceutical company owned the mall. It had been an economic success when it opened in 1975, but all the retail stores had closed in 2017.

Local officials were optimistic that Dharma Pharmaceuticals would create up to 150 well-paying jobs. Growing and processing marijuana was predicted to require high skills, including pharmacists, horticulturists, and legal specialists.

The mall was also being proposed for a gambling casino and family resort, anticipating the General Assembly might loosen Virginia's regulations on gambling in order to spur economic development.

Early plans for the casino projected it would need only 100,000 square feet of the 544,000 square feet at the old mall. However, state regulations required that the area for growing, processing, and selling marijuana products must be 1,000 feet away from the proposed day care facility for workers at the resort's anticipated hotel.

Dharma Pharmaceuticals would need less space than the resort/casino, and made clear that it would consider other locations than the mall if state officials would approve a location change. The city manager for Bristol, Virginia made clear his preference, assuming the casino was authorized:9

Bristol was clearly not in the center of Health Service Area III. It is a two-hour drive down I-81 from Roanoke, and an extra hour distant from Lynchburg. A facility located in the Radford area would have been easier to access for more of the predicted 100,000 customers.

Bristol (red X) was not in the geographic center of Health Service Area III, but I-81 provided easy access

Source: Virginia Department of Health, Health Districts and Health Service Areas - Commonwealth Of Virginia

Dharma Pharmaceuticals may have won the permit purely on the basis of its application, but it may also have benefitted from recognition that Bristol was struggling financially and that opioid overuse was particularly common in Southwestern Virginia.

the medical marijuana license for the Third Health District was awarded to a company based at Bristol Mall, on the edge of the district's boundaries

Source: Virginia Department of Health, Map of Virginia by Health Planning Regions

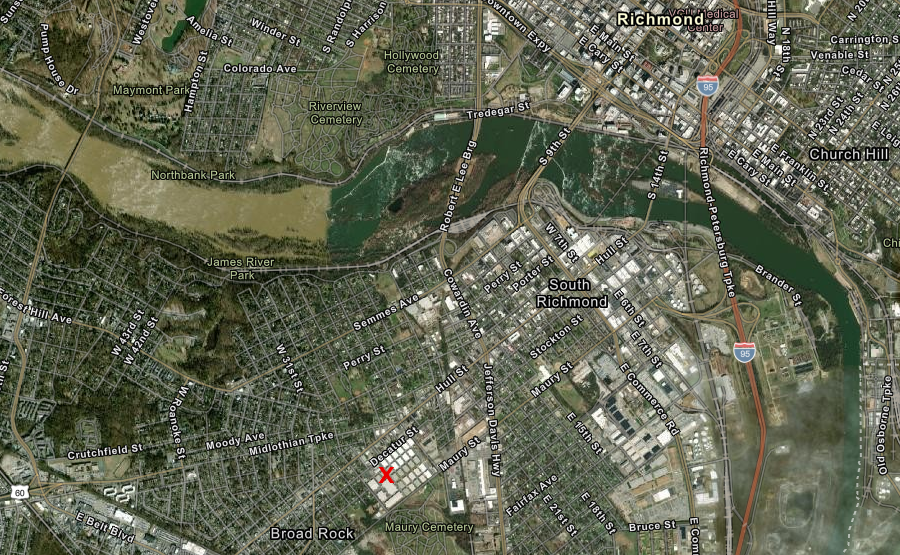

Other licenses were awarded to companies planning to base operations in Manassas, Staunton, Richmond, and Hampton Roads. The Richmond permittee, Green Leaf Medical planned to spend $16 million to develop its site in Manchester south of the James River. The company claimed the retail outlet was:10

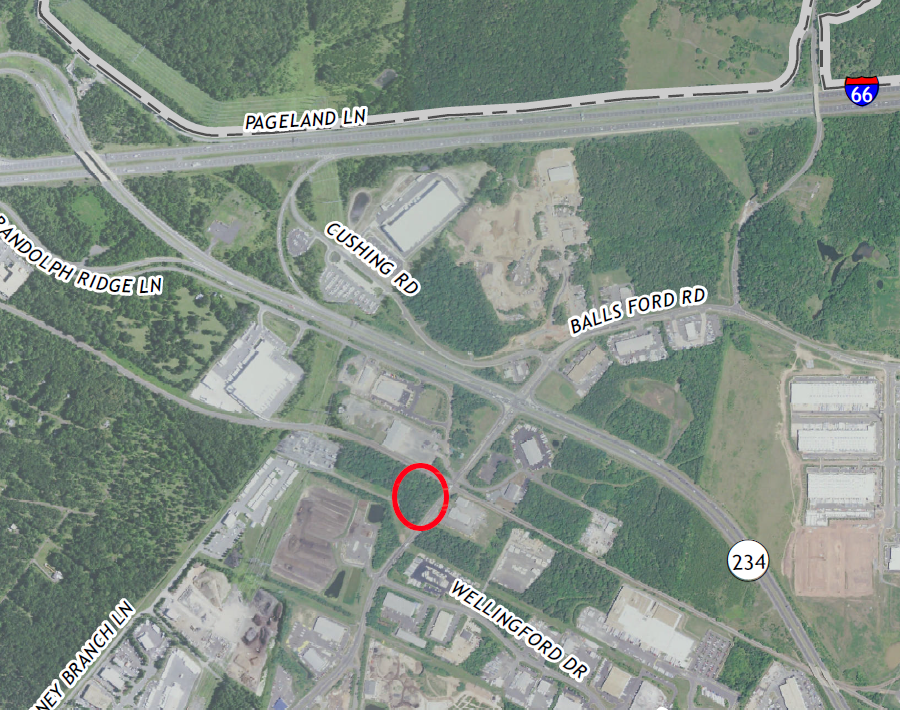

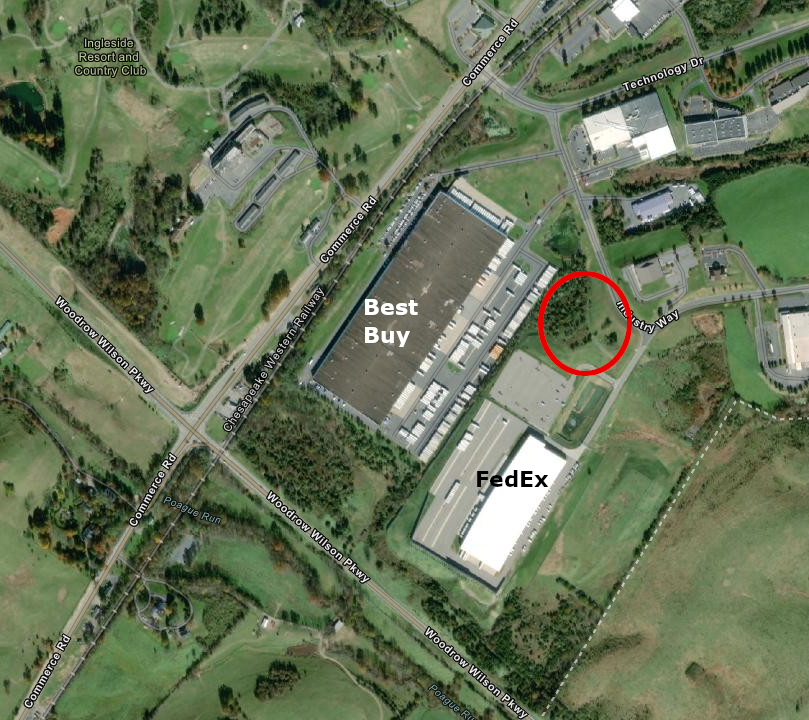

Two of the five companies awarded licenses quickly asked for approval to alter the locations they had proposed. The Board of Pharmacy rejected the request for the Northern Virginia company, Dalitso, to start operations sooner by using an existing building in Gainesville rather than constructing a new building in Manassas.

The company, which branded its operation as Beyond/Hello, ended up constructing a new building. It was in an area zone for industrial use, between the Norfolk Southern Railroad tracks and a Prince William County waste transfer/composting facility, but close to I-66.

Dalitso cleared trees and built a new facility west of Manassas, near I-66

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Gainesville VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2019)

The request by Dharma Pharmaceuticals to relocate the Bristol location to another location, away from the mall, was deferred to a future meeting and then denied. The bidding for the five licenses had included review of specific locations for growing, processing, and selling medical marijuana. The Board of Pharmacy was unwilling to allow the Bristol licensee to change that fundamental component of its bid after winning the contest, even if the result would be construction of a medical cannabis dispensary next to a gambling and entertainment venue.

A local member of the House of Delegates complained that the 4-3 vote for denial reflected geographic ignorance:11

Dharma Pharmaceuticals then proposed, as its second alternative, moving from its original proposed location to a parcel that was adjacent to the mall. It ended up opening in the location proposed in its bid, which was the old JC Penney store at the mall. In the production area, one room was designated as the nursery for the initial growth of plants. Plants were moved to flowering rooms where lights facilitated growth. Another room housed large plants in the "mother phase," before harvest and transfer to a drying room, extraction room, and packaging room. A quarantine room stored product until testing showed it was ready to be sold in the dispensary.

In June 2020, it was clear that the casino is Bristol would be approved by the voters in November. Dharma Pharmaceuticals was notified that its lease for the old JC Penny store would be terminated.

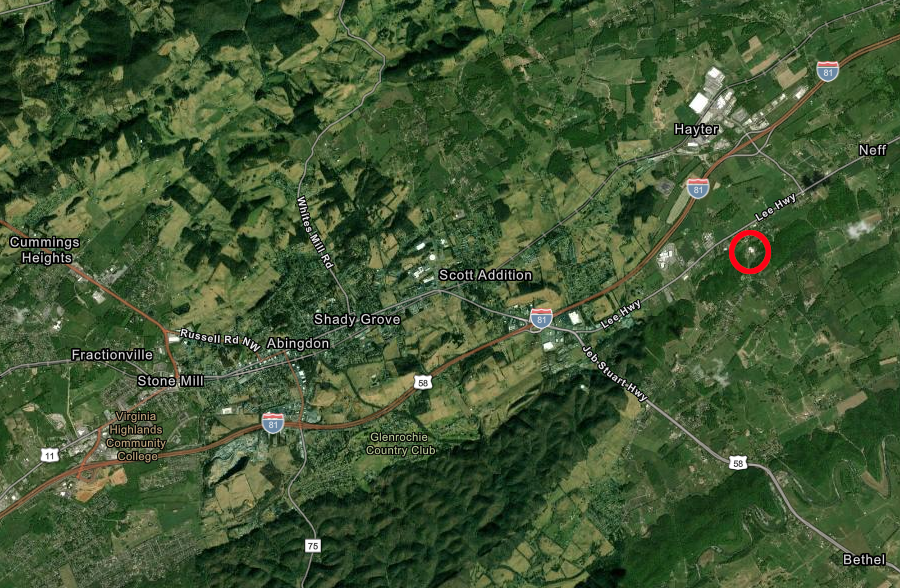

Dharma Pharmaceuticals opened at the Bristol Mall in October 2020, and the next month local voters approved opening the casino there. Dharma Pharmaceuticals acquired a manufacturing facility and got approval from Washington County officials to operate a sales outlet close to I-81 at Abingdon, before applying again to the Virginia Board of Pharmacy to approve moving the marijuana growing, processing, and sales facility.

After getting state approval, Dharma moved to the repurposed manufacturing building on Watauga Road in Abingdon. Two months later, the company was acquired by Green Thumb Industries. That company planned to expand to sell medical marijuana at five other locations as authorized by its permit, including one in Salem that opened in August, 2021. Green Thumb Industries also planned to sell recreational marijuana, after the 2021 General Assembly legalized recreational use in 2021 and authorized sales for recreational use starting in 2024.

In 2023, Green Thumb Industries opened a new 300,000-square-foot manufacturing facility in Alleghany County. It grew, harvested, and dried plants there, then sent material to the Abingdon facility for processing into products for sale.

Governor Youngkin vetoed bills that the legislature passed to establish a legal framework for sale of marijuana for recreational use, but the company had capacity to grow for the recreational market once the political climate shifted. A company representative said:12

Dharma Pharmaceuticals planned a move to Abingdon in 2020, since its lease at Bristol Mall was terminated to make space for casino development there

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

While the state was approving five pharmaceutical processors, CBD-infused products were being sold without clear legal authority in health food store, gas stations, and other retailers. After the US Congress passed the 2014 Farm Bill which support for hemp production, various retailers began to sell hemp-derived CBD products.

Federal and state agencies did not regulate the CBD-infused products, except for Food and Drug Administration approval of Epidiolex for two rare forms of epilepsy. The legality of other CBD-related material was not clear. Consumer safety was not assured, since the Food and Drug Administration was not researching and then approving items for sale.

In 2018, the Powhatan County Sheriff purchased CBD-infused products from retail outlets and had them laboratory tested. One purchased item was pure marijuana, far exceeding the 0.3% threshold of tetrahydrocannabinol defined for creating an intoxicating high. Other items contained synthetic cannabinoids that created the effects desired by Spice users. There were no independent assurances of quality or safety for purchasers of CBD-infused products, so the "buyer beware" philosophy was appropriate.

State police lacked the ability to distinguish CBD-based products from illegal marijuana. In 2019, a state police officer ticketed a man for possession of marijuana. He contested the citation, claiming the hemp flower he had in his possession was purchased legally at a store in Charlottesville selling CBD products. The store submitted a test showing its products had a THC level of .28 percent, below the 0.3 percent threshold that would have made the hemp flower illegal.

A District Court judge ruled that the citation was valid, but upon appeal to Circuit Court the second judge voided the conviction. The State Police on patrol have the ability to recognize marijuana by appearance and odor, but now need a field test that can determine if marijuana products exceed the 0.3 percent threshold.13

The 2019 General Assembly passed three laws to clarify the rights to use cannabidiol (CBD) and THC-A oil. Physician assistants and licensed nurse practitioners were authorized to write a "certification" for patients, patients could designate a registered agents to pick up the products, and students with proper documentation could use CBD and THC-A oil at school. One goal of the increased access was to reduce the use of prescribed opiates.14

The 2019 legislature expanded the right to sell marijuana in edibles and packaged in most every form, from suppositories to lollipops. The legislators declined to described what they had authorized as a "medical marijuana program" and called it a "low-THC oil program." The General Assembly did maintain the ban on the sale of marijuana flowers, thus blocking the opportunity to smoke/vape marijuana legally even with a doctor's recommendation.15

marijuana-infused lollipops, such as those sold in Amsterdam smoke shops, were legalized by the 2019 Virginia General Assembly

Source: Amsterdam Party Guide, Do Weed Lollipops Get You High?

Authorizing sale of medical marijuana could impact sales of alcohol; one study found a 15% reduction. The impact of recreational marijuana could be greater, after it was decriminalized in Virginia by the 2020 General Assembly. The legislature replaced the felony for possession of up to an ounce of the plant with just a $25 civil fine.16

medical use of cannabis required getting a doctor's recommendation, then registering with the Board of Pharmacy

Source: Beyond/Hello

The 2020 General Assembly further increased access to medical marijuana. Pharmacists were no longer required to be on-site for cultivation of plants, and the five authorized processors were allowed to establish five additional off-site cannabis dispensing facilities within the same health service area where they were licensed. With the creation of more outlets, Virginia customers gained 25 more retail opportunities and were no longer obliged to get to the processing facility to purchase cannabis oil, the new term for what had previously been called cannabidiol oil or THC-A.

The legislature refused to authorize medical marijuana to be sold in unprocessed form as "buds." Dropping that ban would have made it far more attractive for users to request a medical decision, then share/sell their medical marijuana for recreational use.17

After PharmaCann was awarded the license for Health District 1, with plans to construct a facility in Staunton, it announced plans to merge with MedMen. The plans were terminated in later 2019, and MedMen ended up with the license. However, the company failed to start construction on the new building for growing, processing, and selling medical marijuana. In December 2019, when state officials visited the site listed in the 2018 conditional permit, it was still an empty lot.

PharmaCann and then MedMen failed to build the planned medical marijuana facility in northeast Staunton behind the Best Buy distribution center

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Virginia Board of Pharmacy refused to grant an extension to MedMen in 2020. The state agency cancelled the license and issued a new Request For Applications. That meant the facility could be constructed anywhere within Health District 1, and could end up being located as much as 100 miles east of Staunton.

Award to a new company was delayed after PharmaCann filed a lawsuit claiming it still owned exclusive rights to the license for Health District 1. The company lost that lawsuit in 2023, opening up the opportunity for the state to select a new supplier of medical marijuana in Health District 1.

The Board of Pharmacy did not try to award a new license for Health Service Area 1 after the court ruling because the General Assembly had transferred responsibility for managing the medical marijuana program to the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority, starting in 2024. The Virginia Cannabis Control Authority decided to issue the new Request for Applications for Health District 1 after the start of 2024, so just one agency could manage the complete process.18

the Health District 1 permit for a cannabidoil processing facility in Staunton was cancelled in 2020, re-opening the possibility of a facility anywhere within the district (red)

Source: Virginia Department of Health, Health Districts and Health Service Areas, Commonwealth of Virginia

Dharma Pharmaceuticals opened Virginia's first medical marijuana dispensary in October, 2020. The facility was located in the old Bristol Mall, as originally planned in the company's application for a state license.19

The second, in Richmond south of the James River, opened one day after Thanksgiving that year. The first harvest by Green Leaf Medical (gLeaf) had been completed in September, 2020 after which the cannabis was processed to create the medical products. The company offered Daily Deals, indicating how medical marijuana was unlike any other product that was available only with a prescription (or "recommendation, in the case of marijuana) from a licensed medical professional.

In the first week after opening, 2,000 patients visited gLeaf and talked in person with a pharmacist to determine which products were most appropriate for their situation. It planned to open its additional five dispensaries in the Richmond area, near the production facility. For its first satellite facility, Green Leaf Medical retrofitted a fast food building in Short Pump with drive-thru windows for sale of Kentucky Fried Chicken and Long John Silver's seafood. That satellite dispensary opened in November, 2021, as the company prepared another site in Richmond's Carytown neighborhood and searched for locations in Ashland and Colonial Heights.

After getting a recommendation from one of over 900 registered medical practitioners and a visit in person to a medical marijuana seller, customers could order online and have the product shipped to their door just like "normal" prescription drugs. Also like prescription drugs, Virginia did not charge sales tax on medical marijuana sales.

Based on sales in other states, gLeaf anticipated that 2.5 percent of Virginia's population would end up as medical marijuana users, and of the 200,000 possible customers there were only 34,000 registered medical cannabis patients after the first year of sales.

The company had a fleet of 20 cars for deliveries to any part of Virginia; though the Board of Pharmacy license restricted grow facilities and dispensaries to a particular health district, the medical marijuana companies were free to compete statewide for delivery customers. Delay in awarding the license for Health Service Area 1 made Staunton and the Shenandoah Valley a prime candidate for delivery from Richmond.

Columbia Care, which had purchased gLeaf, used that company for its initial deliveries in Hampton Roads. Columbia Care planned to set up its own delivery service and to open satellite dispensaries in Virginia Beach, plus two on the Peninsula. In preparation, Williamsburg modified its zoning ordinance to authorize licensed medical cannabis dispensaries in the city's Economic Development District (ED).

A company spokesman noted that gLeaf had sought the license for Central Virginia because the logistics of home delivery were easiest from there. The company could compete with the other four authorized providers for sales:20

gLeaf started selling medical marijuana products with daily deals

Source: gLeaf, Richmond, VA Soft Opening

gLeaf opened its medical marijuana facility in the Manchester area of Richmond after Thanksgiving, 2020

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The third facility to open was the Dalitso operation in Prince William County. Its business, branded as Beyond/Hello, opened on December 1, 2020.

The first crop was 6,000 pounds of dried flower, and appointments at the dispensary were almost fully booked within a month. The facility was sized to produce 27,000 pounds of dried flower annually, accommodating demand from more patients and the ability to supply other sales outlets and provide home delivery. In December 2020, Jushi Holdings Inc. completed acquisition of the last 21% of Dalitso required to own 100% of the company.

At the start, Beyond/Hello signed up 5,000 patients. By the end of 2021, a year after opening, that number had grown to nearly 50,000.

The company announced plans in April 2021 to open a second Beyond/Hello outlet in Loudoun County. The Sterling outlet opened in November, 2021, while Jushi Holdings sought new facilities with drive-through widows and 50 parking spaces in Alexandria, Arlington and Woodbridge.

The company planned to spend $2 million on each dispensary, and expected the six outlets would serve a regional population of 2.5 million people. In early 2023, Jushi Holdings obtained Prince William County approval to expand its growing/process/retail facility. The investment of up to $150 million would add 65,000 more square feet to the 96,000-square-foot facility.

Jushi Holdings considered the limited market, with Virginia law authorizing just one company per Health Service Area (HSA), to provide competitive advantage. One company executive said in late 2021:21

Dalitso branded its operation in Prince William County as Beyond/Hello, before Jushi purchased Dalitso in December 2020

Virginia was the fourth state in which Dalitso opened a Beyond/Hello medical marijuana facility

Source: Beyond/Hello

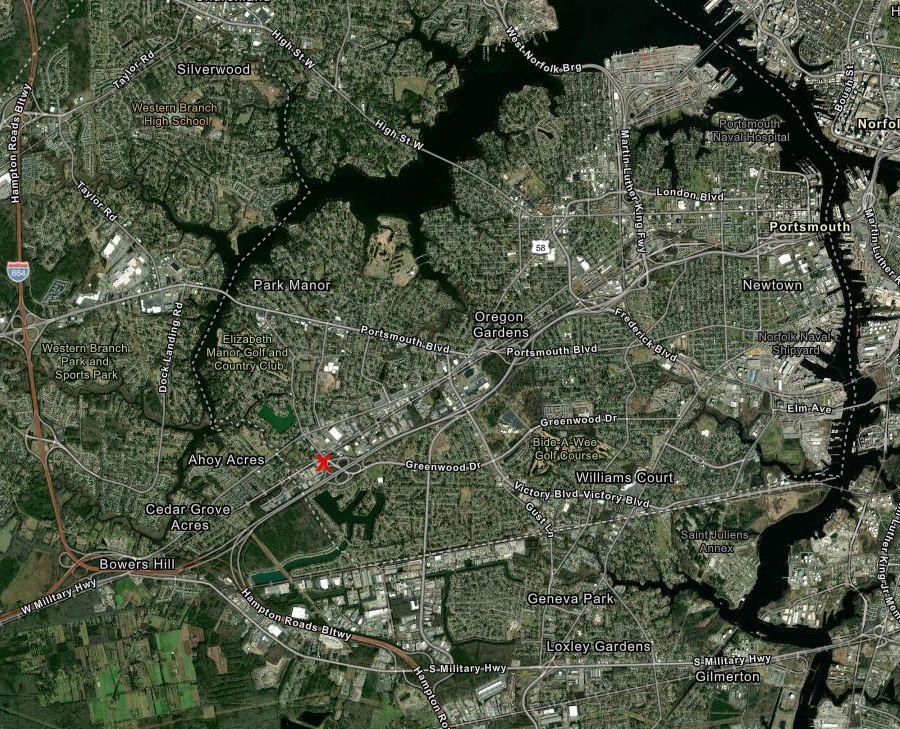

At the end of 2020, the two firms with licenses for Richmond and Hampton Roads agreed to consolidate. Columbia Care, which opened its facility in Portsmouth with a soft launch on December 29, purchased Green Leaf (gLeaf) with the license for medical marijuana in Richmond. That consolidation enabled Columbia Care to start operations in Portsmouth by selling gLeaf products.22

Columbia Care located its facility in Portsmouth

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

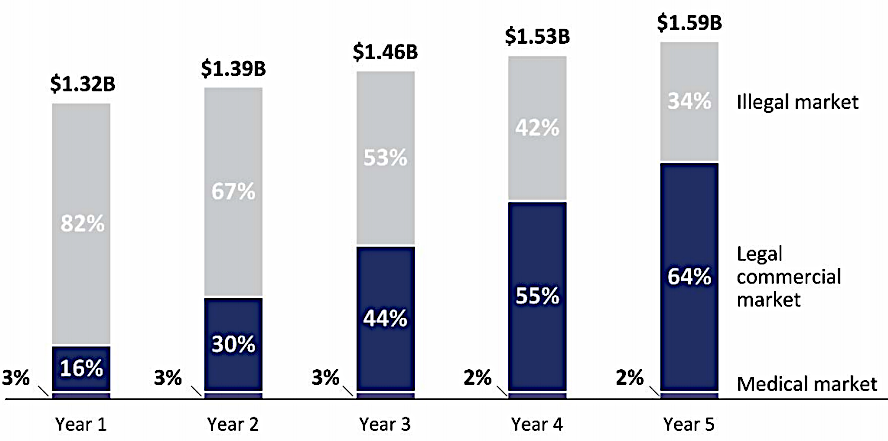

In November, 2020, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission released a report on policy choices that could be made by the General Assembly if it chose to legalize recreational use. Governor Ralph Northam then endorsed such legalization.

The state agency calculated that legal marijuana, with a total tax rate no higher than 30%, could capture almost 2/3 of the total market within five years. Legal medical marijuana sales were estimated to be just a tiny component (2-3%) of the overall market for the drug.

the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) estimated in 2020 that legal marijuana sales, taxed at 30%, could capture 2/3 of the illegal market

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), Key Considerations for Marijuana Legalization (Figure 10-2)

Legalization of recreational use could have a significant impact on sales by medical marijuana processors. The state could protect the nascent industry by taxing medical marijuana at a lower rate that sales for recreational use, and it could give medical providers an early authorization to sell for recreational use as well. Market demand was expect to be far higher than what the medical marijuana outlets could satisfy. In Colorado, "green cross" dispensaries quickly became ubiquitous in retail centers.

Though initial state regulations limited sales to just the facilities where the medical marijuana was grown and processed, the state quickly authorized each of the licensed companies to sell at five outlets in their health district. Full legalization of recreational use by 2024 was expected to lead to a surge of dispensaries selling marijuana to retail customers.

Danville and Portsmouth were the first cities to update their planning and zoning ordinances to regulate where marijuana could be sold. A land use planner in Bristol identified why that city was updating its ordinances in 2021:23

At the time Columbia Care opened two of the first medical marijuana stores in Virginia, the company was a multi-state operator with licenses in 10 states and Washington DC. It did not anticipate creating a national brand because of the Federal ban on transport across state lines, preventing any blending process to standardize an agricultural product grown at separate facilities. Expectations of investors that they could identify a single company which could establish market dominance had not been realized.

Columbia Care decided to focus on selling "Seed & Strain" products which would be slightly different in flavor and impact in every state, and even within each state as various crops were harvested. Customers would recognize common characteristics from different strains, but would accept that the experience would not be consistent. A Columbia Care official said clearly:24

The company reversed course in 2022, when Columbia Care agreed to be acquired by Cresco Labs for $2 billion. That merger would have created a much larger single company, and would have required divestiture of assets in Massachusetts, New York and Illinois. The deal was terminated by mutual agreement in 2023, at which time Columbia Care announced plans then to lay off 52 people.25

In 2021, the General Assembly finally legalized possession of marijuana for recreational use. The law created the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority to establish procedures and administer sale of recreational marijuana by the start of 2024. In 2023, the General Assembly transferred responsibility of medical marijuana oversight from the Board of Pharmacy to the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority, starting in January 2024.

The legislature focused on consideration of social equity when authorizing 400 licenses for sale of recreational marijuana and 450 licenses for growing it. Sale of marijuana for recreational use created new business opportunities and tax revenue, which could be directed to address systemic racism and discrimination in previous enforcement of drug laws.

The Virginia Cannabis Control Authority was directed to limit vertical integration to small businesses when issuing licenses for marijuana cultivation, manufacturing, wholesale operations or retail sales. Medical marijuana producers and industrial hemp operations were required them to pay a $1 million fee before such large businesses could get any license associated with recreational marijuana:26

when the General Assembly legalized marijuana possession for recreational use in 2021, it did not alter the established medical marijuana sales process

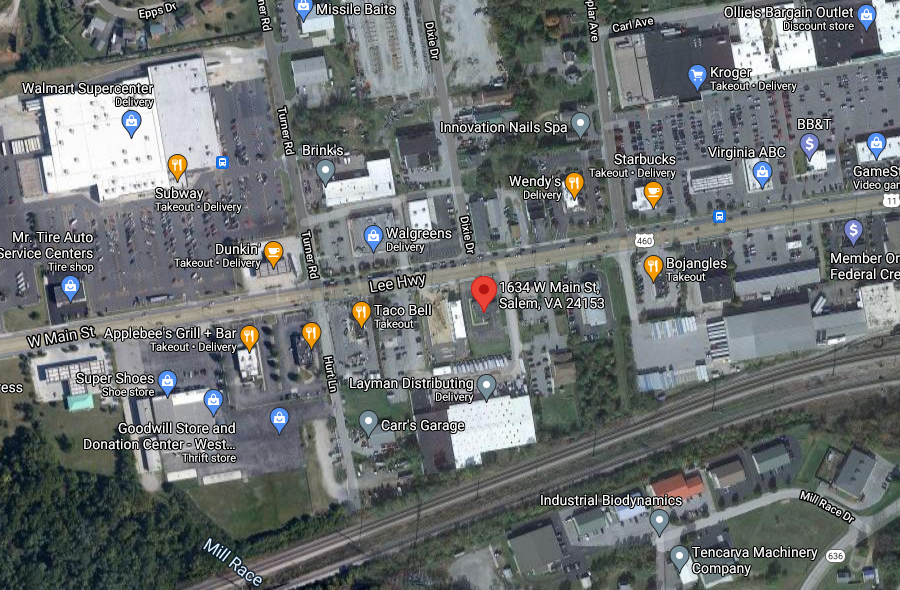

After Green Thumb Industries acquired Dharma Pharmaceuticals, it took advantage of the General Assembly's authorization in 2020 for medical marijuana sellers to open five additional outlets within their health district. The former Floyd's Bank building in Salem was converted to a sales outlet with drive-through service in August, 2021. The RISE Salem outlet was purely for sales; all the marijuana was grown and processed in Abingdon.27

The 2021 General Assembly relaxed the initial ban on sale of medical marijuana products that could be smoked, rather than just products manufactured with extracted oils. Concerns about diversion of medical marijuana to recreational use diminished. In 2021, the legislature legalized recreational use and growing marijuana at home, and prepared to legalize sales for recreational use.

Medical marijuana producers argued that extraction of oils sacrificed some of the minor cannabinoids and terpenes that were present in whole flower cannabis, but it was also clear that the companies were positioning themselves for the future business of selling for recreational use.28

A year after the first medical marijuana sales, the Virginia Board of Pharmacy had approved 33,000 applications and issued cards for purchasers to use at the authorized dispensaries.

The number of customers was low, and costs for selling medical marijuana were high. One factor was the requirement for a licensed pharmacist to be present where medical marijuana was sold. That requirement was not common in other states which authorized sale of medical marijuana, and may have reflected the priorities of the Virginia Board of Pharmacy to enhance business opportunities for pharmacists more than a standard medical need.

Sellers of medical marijuana set high prices in order to generate sufficient revenue to be profitable. Only four operators were in business in October, 2021, and Columbia Care controlled two of them, so customers had little opportunity to comparison shop.

In the District of Columbia, Columbia Care's outlet sold 3.5 grams of marijuana for $35. Customers buying from the Richmond and Portsmouth dispensaries had to pay $65 for the same amount. The cost was high enough to incentivize some customers to grow their own marijuana plants after July 1, 2021, once that was legalized by the General Assembly.

Various companies emerged to connect potential patients with doctors who would recommend use of marijuana to relieve a wide range of ailments. Those patients could get a card quickly, but registration with the Virginia Board of Pharmacy was slow. The state agency was receiving an average of 1,000 applications each week by late 2021, and was taking 4-6 weeks to process them.

doctor recommendations could be obtained in 24 hours, but in late 2021 the Virginia Department of Pharmacy required 4-6 weeks to issue cards needed to purchase medical marijuana

Source: MediCardVA

By 2022, out of over 40,000 doctors, physician assistants and nurse practitioners authorized to certify a patient needed medical marijuana. Only 703 had registered with the Virginia Board of Pharmacy, but telehealth appointments were easy to get and patients were not facing serious delays in completing that step of the process.

The problem was at the Virginia Board of Pharmacy, which had a backlog of 8,000 applications. The state agency had registered less than 50,000 patients for medical marijuana use, about 0.06% of the state's population. In response to the delays, the 2022 General Assembly changed the law and eliminated the requirement for patients who had been certified by a registered practitioner to deal with the Virginia Board of Pharmacy. Dispensaries were authorized to sell medical marijuana to patients once a registered practitioner had certified their need.

A vice president of Columbia Care complained that the delay in issuing new cards was constraining sales:29

The 2021 General Assembly decriminalized use of marijuana for recreational purposes, but created no legal mechanism to grow, sell, or purchase marijuana for recreational use. The legislature established 2024 as the deadline for starting recreational sales, because the legislators could not agree on procedures and the timeline for growing, processing, and selling marijuana for recreational use. Those details, including whether "equity" would be a factor in how licenses would be awarded, were postponed for decisions by the 2022 General Assembly and the new governor elected in November 2021.

The 2022 General Assembly did eliminate the requirement for medical cannabis patients to register with the Virginia Board of Pharmacy, and in that process eliminated the application and renewal fees for those registrations. Once patients obtained approval from a registered medical cannabis practitioner, they could go directly to a medical marijuana provider to purchase products. When the registration requirement was dropped at the end of June, 2022, the Virginia Board of Pharmacy had registered 52,810 medical cannabis patients and had a backlog of 4,900 more applications.

The relaxation of the authorization process led to a "nice little uptick" in demand. Jushi Holdings Inc., which sold medical marijuana in Northern Virginia under the Beyond Hello label, had already invested $75 million in a production facility near Gainesville. It bought adjacent property and announced plans to spend up to $75 million more to expand production.

Because Maryland voters had just approved recreational marijuana in 2022, Jushi had the potential to expand both wholesale and retail sales. The company could anticipate the Virginia legislature would accelerate its timeline to create a legal process for sale of recreational marijuana within Virginia, before Maryland established its retail sales outlets and attracted Virginia customers.

The 2022 General Assembly also was able to pass legislation regulating synthetic marijuana and Delta-8 products. It clarified that edibles infused with a chemically-synthesized cannabinoid must comply with the Virginia Food and Drink Law. That restriction on adulterating food items was intended to close down the "wild west" marketplace which had developed for THC-infused edibles, with packaging designed to resemble popular candy and snack items.

The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services announced that the Attorney General would enforce the amendments to the Virginia Consumer Protection Act (VCPA):30

Governor Youngkin proposed an amendment that would redefine possession of more than two ounces. The legislators rejected the amendment, and SB 591 died in the 2023 veto session.31

Because Virginia restricted the right to sell medical marijuana within a health district to just one company, competition was limited. That affected prices. Product that sold for $60 in Virginia in 2023 cost just $35 in Pennsylvania. Virginia dispensaries charged an average of $14 per gram compared to $10 per gram in Florida and Pennsylvania, and just $9 per gram in Arkansas. Twice as many medical marijuana users in Virginia were buying from non-licensed dealers or growing plants and home, compared to purchasing medical marijuana from one of the legal dispenaries.32

The 2022 and 2023 General Assemblies both failed to create a framework of laws for recreational use, so no regulations or legal procedures for recreational sales could be prepared. Investors struggled to assess the legal business opportunities, but illicit distribution channels expanded. Illicit sales created some competition for the companies licensed to sell medical marijuana. Quality control was less reliable for the illicit product, but that was not a new issue for the customers.

The handful of companies with licenses to sell medical marijuana positioned themselves to establish retail outlets quickly that sold marijuana for recreational use, compared to the anticipated "new starts" once the General Assembly acted. Dispensaries sold vape cartridges and other products which were popular with people using marijuana for recreational purposes, but the medical marijuana companies offered few tinctures, edibles, tablets, or suppositories desired for medical use. Companies invested in Virginia's small medical marijuana business in order to gain a "first to market" advantage, once the much larger recreational market became legal.

the first sales outlet for medical marijuana in Salem (red marker) offered drive-through service across the street from a WalMart, and was well-positioned for future distribution of recreational marijuana

Source: GoogleMaps

To improve influence with state decisionmakers, Jushi hired as a lobbyist the man who had served as Governor Northam's Secretary of Public Safety. Jushi was interested in getting authorization to sell marijuana for recreational use sooner than 2024.

An Illinois-based company purchased the medical marijuana license for the Hampton Roads region (Health Service Area 5) from the Cannabist Company in 2024. Verano bought the growing facility plus the six dispensaries in Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Portsmouth, Suffolk, Hampton and Williamsburg for $90 million.

The Cannabist Company, formerly known as Columbia Care, retained its license for the Richmond region. It continued to operate there under the name gLeaf.

medical marijuana retail sales outlet in Williamsburg

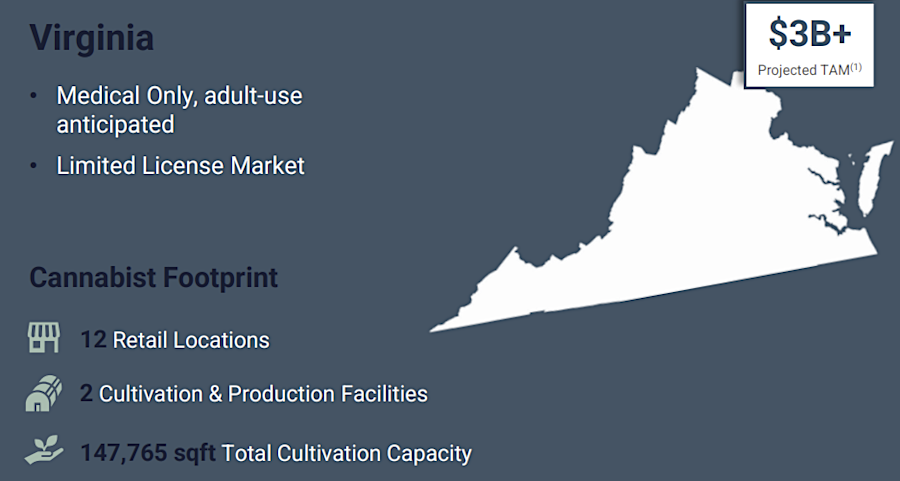

The Cannabist Company had estimated in 2024 that medical marijuana sales across Virginia would total almost $150 million. After legalization for recreational use, sales could expand to $3 billion per year. Selling the Hampton Roads operation to a competitor generated cash for The Cannabist Company. Retaining control over the Richmond area market kept open the potential for statewide retail sales, once the General Assembly legalized a retail market for recreational use.

A proposal to sell the remainer of Cannabist's operation in Virginia to Cresco Labs in 2024 fell through. In December 2025, Curaleaf announced plans to purchase the gLeaf assets in Central Virginia (Health Service Area 4), including the sixth dispensary that was not open yet, for $110 million. Curaleaf already operated in 17 states, with over 150 dispensaries and 19 cultivation facilities.

Curaleaf was quickly outbid by Millhouse Capital, which acquired the gLeaf assets for $130 million. Considerating all the components of the sales, the Cannabist Company ended up being paid nearly $250 million in 2024 and 2025 for its two medical marijuana licenses.

The price reflected the market value not of the medical business, but of the opportunity to get a quick start in selling recreational marijuana. It was obvious that the 2026 General Assembly would create a legal retail market for sale of marijuana for recreational use and the new governor elected in 2025, Abigail Spanberger, was prepared to sign a legalization bill which Governor Glenn Youngkin had consistently rejected.33

based on the Total Addressable Market (TAM) in Virginia and assuming legalization of sales for recreational use, legal marijuana sales could climb from $150 million in 2024 to $3 billion in 2028

Source: The Cannabist Company, Investor Relations Presentation (First Quarter, 2024)

The Cannabist Company made clear that its medical marijuana products were intended to be intoxicating

Source: The Cannabist Company

One sign of public support for marijuana legalization was the attendance at the first Lazy Lake Daze festival held at Palmer Springs in Mecklenburg County in 2022. Cannabis Cultivators of Virginia organized the event to promote the positive health benefits of cannabis, and claimed 1,800 people attended.34

The path to open new retail outlets was not smooth. In 2022, Chesterfield County officials refused to issue a building permit to gLeaf to remodel a store into a medical marijuana dispensary. The county cited Federal law, which still treated marijuana as an illegal drug without authorization for medical use. gLeaf appealed to the county's Board of Zoning Appeals. The company argued that local officials were obligated to follow state law when making land use decisions, and that the Federal classification of marijuana was irrelevant because the General Assembly had authorized use in Virginia.

in 2022, Chesterfield County denied a building permit in an attempt to block conversion of a T-Mobile store near Chesterfield Towne Center into a medical marijuana dispensary

Source: GoogleMaps

The Board of Zoning Appeals for Chesterfield County had previously heard one appeal from a store in Chester selling cannabidiol (CBD) products. After Virginia decriminalized possession of up to one ounce of marijuana with high THC levels, the store opened a "bring your own" smoking parlor. The Board of Zoning Appeals upheld the county's decision that the smoking parlor was not an allowed use under the zoning code, and the CBD store eliminated it.35

Green Thumb Industries, which had opened the state's first dispensary in Bristol, recognized many customers were driving to Bristol from Danville. Both cities were planning for economic revitalization triggered by new gambling casinos, so Green Thumb Industries opened in Danville the last dispensary that was authorized in Health District III. The growing/processing/sales site in Bristol then served five distribution dispensaries in Abingdon, Christiansburg, Lynchburg, Salem, and Danville.

All four of the authorized medical marijuana providers anticipated that the 2024 General Assembly finally would create a mechanism for legal sales of marijuana for recreational use, and existing dispensaries would give these companies a competitive head start for recreational sale. Only in Health District I (Northwest Health Planning Region), where no medical marijuana license had been issued, would new competitors face a level playing field.

by the end of 2023, no medical marijuana license had been issued for the Northwestern Health Planning Region (Health District 1)

Source: Health Systems Agency of Northern Virginia, Virginia HPRs & Health Districts

When opening the dispensary in Danville, however, a Green Thumb Industries official focused on the medical benefits of marijuana:36

A report by the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority six weeks before the opening of the 2024 General Assembly concluded that there was limited business opportunity to incentivize the four existing licensed pharmaceutical processors to improve service or product availability within Virginia:37

Rather than pay $14-19 per gram for flower products sold by licensed dispensaries in Virginia, customers were paying $8.73 per gram in Washington, D.C. or $9.27 per gram in Maryland. A majority of medical marijuana users were choosing to grow at least some cannabis at home, or obtaining it from other growers through unlicensed mechanisms.

The state's regulatory system limited licenses to just one company in each of the state's five Health Service Areas. Competition between the authorized providers would not impact prices by authorizing each one to open more than a total of six stores per provider, including the facility where marijuana was grown and processed. By the time the report was issued, the four licensed providers (no license had been issued yet for Health Service Area 1), had opened 21 sales outlets of the 24 authorized.

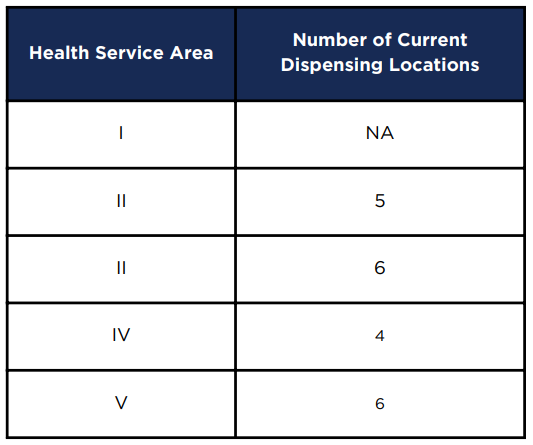

by November 2023, two of the four licensed providers had not spent the resources required to open all authorized sale outlets

Source: Virginia Cannabis Control Authority, An Examination of the Virginia Medical Cannabis Market (Table 2)

As perceived by the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority, the four current licensed providers were charging fair prices. Fundamentally:38

The report did not assess the potential impact of creating a legal market for commercial sale of marijuana for recreational use in Virginia.

In 2024, the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority received 41 applications for the one remaining medical marijuana license in Health Service Area (HSA) 1. Each applicant paid an $18,000 fee for the opportunity to win the exclusive right to establish a legal growing operation and open retail stores in that region. HSA 1 covered 24 counties and 8 cities, including the Shenandoah Valley, Charlottesville, and Fredericksburg.

Since the PharmaCann license was revoked in 2020 for failure to complete construction by the deadline, there had been no authorized processor in that part of Virginia. Customers had to order online and have medical marijuana shipped to them, drive to an authorized sales outlet in another HSA region, grow their own, or acquire marijuana through a non-legal process.

The number of applicants demonstrated that investors saw potential profits in the Health Service Area 1 (Northwestern Virginia) license. Governor Youngkin had vetoed the bill passed by the 2024 General Assembly to authorize retail sale of marijuana for recreational use. A future compromise still had the potential to allow medical marijuana providers to start retail sales before competing stores could open.

Medical marijuana was selling at $14 per gram in Viginia, 40% higher than in Florida and Pennsylvania. In addition to the state-required application fee, preparing a proposal cost up to $500,000. The potential profit for the company winning the license was clear, since there had been 3.4 million medical cannabis dispensations in 2023. The investment in applying for the HSA 1 license was described by one company as:39

On September 5, 2024, the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority finally selected a medical marijuana provider for the Health Service Area (HSA) 1 region. After applications were evaluated, the top 33 received the same priority ranking. A lottery was used to make the final decision, which awarded the license to AYR Virginia. It was a subsidiary of AYR Wellness, a company which already had cannabis operations in eight states.

One applicant noted that the equal ranking was not unexpected:40

Seven unsuccessful bidders filed suit in Richmond Circuit Court against the Cannabis Control Authority, claiming that the selection by lottery did not qualify as a genuinely competitive bidding process. All 33 were ranked as having 8 out of the possible 16 points that could be earned. Previous awards had used a 275-point scale in the scoring system.

One applicant was accused of filing multiple applications so it would have a greater chance of winning the lottery; 21 companies affiliated with TheraTrue were among the 33 companies in the lottery. The Cannabis Control Authority (CCA) told applicants before the filing deadline:41

Because of the delay in the award of that medical marijuana license, Kealth District 1 had no established legal provider already connecting with customers at dispensaries. That made the Shenandoah Valley region a prime candidate for other companies who planned to enter the recreational use market. There was no entrenched provider in Health Service Area 1 with operating dispensaries that could quickly start to sell marijuana to the much larger market for recreational use.42

The Virginia Cannabis Control Authority implemented a Seed-to-Sale tracking system in 2025, using the private contractor Merc. The data revealed that customers were purchasing $15 million/month of medical marijuana from the 23 operating dispensaries. Customers paid no sales tax because they were buying a medical product.

In the first two months of tracking (July/August, 2025), producers of medical marijuana recorded:43

The system also identified which products were chosen by patients, including the loose residue after processing flowers ("shake trim"):44

Because use of medical marijuana was a new health management tool, documenting the actual health benefits of various approaches required new esearch. The Cannabis Product Committee of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a handful of cannabis-derived and cannabis-related drug products that are available with a prescription for treatment of seizures, anorexia, and nausea. Based on research accepted by the Federal agency, those drugs are safe and effective for their intended use.

Claims that many other cannabis-related products can be used for therapeutic purposes have not been accepted by the Food and Drug Administration. The agency says that no THC or CBD product qualifies as a dietary supplement. Hulled hemp seed, hemp seed protein powder, and hemp seed oil are the only Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) products that can be added to food. Interstate sales of drinks, gummies, candies, and other food products to which THC or CBD have been added violates Federal law. Cosmetic products are not food, however.

For decades, marijuana was listed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was responsible for enforcing the controlled substance laws for products not authorized by the Food and Drug Administration.

By 2025, use of cannabis had become a $32 billion industry. Only a small percentage of those sales were for pharmaceutical-grade cannabinoids approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Scientific trials found little evidence that non-approved products reduced pain, insomnia, psychiatric disorders, arthritis, or Parkinson's disease - but did see effects on reducing anxiety.

A doctor researching the benefits of medical marijuana concluded:45

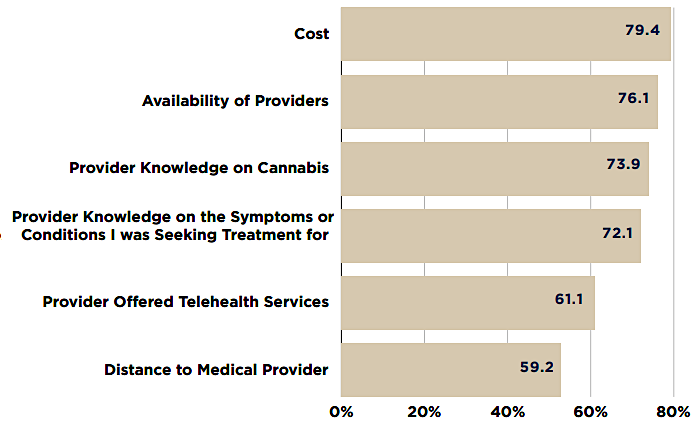

Factors Influencing Patients' Decision When Choosing a Provider to Certify Them for Medical Cannabis

Source: Virginia Cannabis Control Authority, An Examination of the Virginia Medical Cannabis Market (Figure 7)

In 2024 President Biden started the process to reclassify marijuana as a Class III drug, acknowledging that it had some medical benefit. A year later, President Trump renewed that initiative, claiming that a primary benefit of reclassification would be an increase in research related to health benefits.

The new designation, once completed in 2026, would legalize medical marijuana at the Federal level. Products with high tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) levels could be prescribed and sold at pharmacies to patients with a doctor's prescription, just like other Class III drugs regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (such as Tylenol with codeine).

Medical marijuana advocates feared that reclassification to Schedule III would end up limiting the use of medical marijuana:46

In 2026 the Virginia General Assembly was expected to pass another bill creating a legal retail market for selling marijuana for recreational use. With the election of Abigail Spanberger as governor in 2025, it was clear that the legalization bill would no longer be vetoed.

Legislators sought a way to ensure small businesses, and communities impacted by marijuana enforcement in the past, would have an opportunity to compete against large corporations. The existing medical marijuana distribution network gave the companies with state licenses a head start. They had a pre-existing customer base, experience in operating growhouses, detailed understanding of the genetics of different strains, administrative expertise in tracking and ensuring compliance in the transfer of marijuana from seed to sale, and existing outlets for selling and delivering products.

The candidates for the 350 licenses proposed by the Joint Commission on the Future of Cannabis Sales in December 2025 feared that they would be overwhelmed by marketing and extra-low sale prices from larger companies.

Based on the advantages of the existing operators to dominate the recreational sales business, legalization proposals include a one-time fee to allow medical marijuana providers to obtain a license for recreational sales. A small hemp cultivator said:47

In 2025, state officials were discussing requiring the already-authorized medical marijuana companies to pay a $10 million fee to gain the right to sell marijuana for recreational purposes. One advocate for a $20 million fee wrote:48

The investment required to grow medical marijuana over four-five months is significant. The process starts not with planting seeds but by creating clones from "mother" plants. The genetically-identical plants are grown indoors, starting first in rooms with lights turned on for 18 hours/day. Fans provide constant ventilation to reduce growth of mold and mildew.

After about a month of growth, plants are moved into a flowering room. Lights are kept on for just 12 hours per day, and both humidity and temperature are reduced. The goal is to produce the trichomes on the plant, from which cannabinoids and terpenes are extracted. Producing the relatively-unstable terpenses requires careful attention to environmental conditions.

Virginia created a medical marijuana program in 2020 that, unlike other states, combined into one license the right to grow, process/package, and sell marijuana. As the 2026 General Assembly prepared to authorize commercial operations for recreational use, companies with medical licenses were well positioned to establish dominant control over the supply of the raw material.

The medical providers had the only four licensed growhouses in the state that could scale up quickly and create recreational products while still tracking materials seed-to-sale. They expected to be grandfathered into a state regulatory system that prevented other retailers of recreational marijuana from owning their own growhouses. Competitors would be forced to pay wholesalers a profit in order to obtain product, a cost the vertically integrated medical marijuana business could avoid.

Companies that might get new licenses for recreational use could contract with farmers already growing industrial hemp, and farmers might even organize co-ops to process the raw material into products ready for sale. However, the risk of a cash flow interruption from weather or insects one year when growing hemp outdoors was a factor.

The alternative was to grow indoors, but setting up a growhouse was a capital-intensive business. Still, growing plants indoors was essential to creating a consistent product. As noted by one medical marijuana cultivator:49

Indoors, trichomes are cut from the plant, then dried and cured for a week. Tight temperature and humidity controls allow for removal of most of the moisture in the plant cells in a process described as "burping." The cannabinoids and terpenes can be extracted using a hydrocarbon solvent. The resulting oil is heated into a gas, then condensed under pressure to form a slurry that is distilled with ethanol to separate the different terpenes and cannabinoids. Those products also can be generated by a separate process, by baking trichomes in an oven.

The final step is to mix the terpenes and cannabinoids with other materials and to package them into gummies, candies, vape cartridges, and other items sold to customers.50

by 2022, customers could get medical marijuana delivered just like a pizza

Source: Beyond Hello, Virginia