state-authorized industrial hemp growing in Augusta County

state-authorized industrial hemp growing in Augusta CountySource: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Annual Report on the Status and Progress of the Industrial Hemp Research Program (2018)

state-authorized industrial hemp growing in Augusta County

state-authorized industrial hemp growing in Augusta County

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Annual Report on the Status and Progress of the Industrial Hemp Research Program (2018)

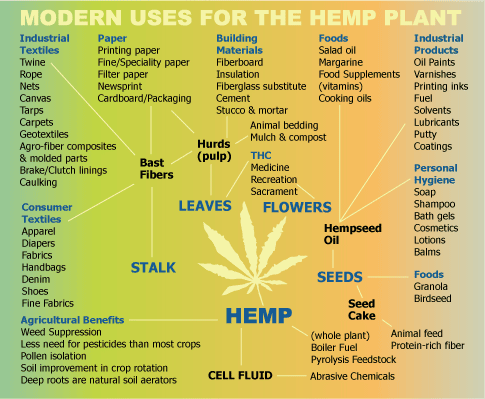

Cannabis sativa evolved as a distinct species about 28 million years ago in East Asia. It was domesticated about 12,000 years ago, probably for its fibers and oily seeds but potentially also for its psychoactive capabilities. Around 4,000 years ago, humans created two strains. One produced better fiber, and one that produced more psychoactive effects. Traders brought hemp to Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, and finally to the New World after 1492.

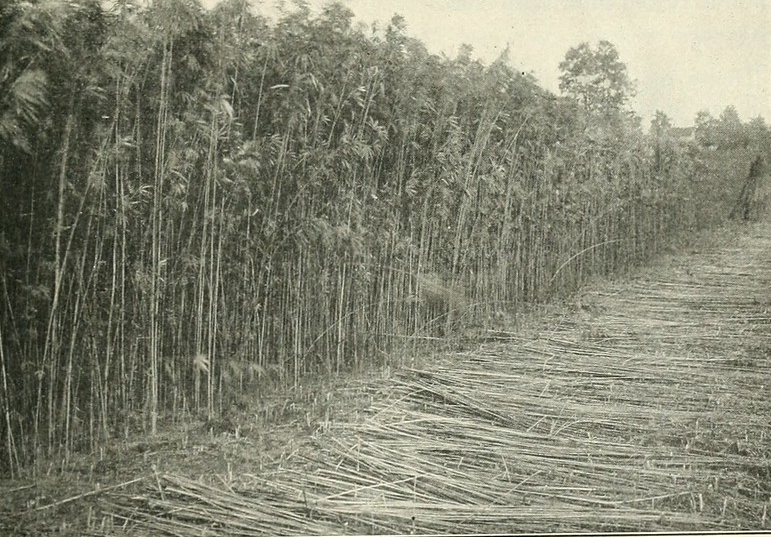

When Virginia was colonized by Europeans starting in 1607, England needed hemp fiber for sails and rope. To increase the supply, in 1632 the General Assembly passed a law requiring every planter to grow hemp. It was a profitable crop throughout the era of sailing ships. In the Shenandoah Valley, plants as much as 14 feet tall provided long fibers. Those fibers were valuable for the ropes needed by merchant ships and warships.

The long hemp fibers were more cost-effective for manufacturing rope, sails, and caulking than the other fibers of the day - silk, cotton, wool and flax. Demand was steady; a single British warship could require 20 or more miles of rope. Even after it was covered in tar, rope wore out from heavy use and exposure to sun and saltwater and had to be replaced.

While sails could be manufactured from hemp fibers, in North America flax fibers (linen) were most popular. In the 1800's, long-fiber cotton became the preferred material.

Before the American Revolution, acreage use for hemp reached 25% of the acreage dedicated to tobacco. The demand for hemp basically disappeared as wooden sailing ships were replaced by coal-powered iron ships. In the early 1900's, the reputation of hemp became associated less with industrial shipping and more with recreational use by jazz plus rhythm and blues musicians.

The Marijuana Tax Act in 1937 and the Controlled Substances Act blocked farmers from growing hemp. The tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration in the plant was irrelevant; hemp was defined as marijuana, and growing it was banned.1

In 2014, the US Congress authorized state agriculture departments and universities/colleges to grow hemp, so long as the tetrahydrocannabinol concentration did not exceed 0.3 percent. Within Virginia, James Madison University (JMU), University of Virginia (UVA), Virginia State University (VSU), and Virginia Tech (VT) began research programs. In 2018, the state authorized private institutions of higher education to join in the research.

In 2016, the four state-owned universities planted 37 acres in hemp. By 2018, that grew to 135 acres on both privately-owned land and public land. Virginia State University grew marijuana on its Randolph Farm in Chesterfield County. Virginia Tech grew the crop at Kentland Farm in Montgomery County, the Northern Piedmont Center in Orange County, the Southern Piedmont Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Nottoway County, and the Tidewater Agricultural Research and Extension Center in the City of Suffolk.

The University of Virginia research tested five varieties on farms in Albemarle, Augusta, Fluvanna, Lee, Northampton, Scott, and Wythe counties, plus development of strains that would produce high percentages of cannabidiol (CBD) under greenhouse conditions. Weeds out-competed hemp in many trials, unless a burndown herbicide had been used to prepare the field. Fields planted in July after harvesting hay, without herbicide use, produced a crop of weeds rather than hemp. Growing fields of industrial hemp organically in Virginia will be a challenge.

industrial hemp growing in August 2018, as part of James Madison University research

industrial hemp growing in August 2018, as part of James Madison University research

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Annual Report on the Status and Progress of the Industrial Hemp Research Program (2018)

The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services tested the hemp grown by the universities. In most samples, the plant material had a tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration below 0.3 percent. Four samples exceeded the threshold, and in one case the concentration was 1.86 percent.

Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services got a permit from the Drug Enforcement Administration to import hemp seeds from international sources, then supply them to the universities. The Federal agency would not specifically authorize transport of domestically-produced seed across state boundaries, but the Virginia Attorney General assured the universities that their permits would not be jeopardized if domestic seeds were acquired.

The official state report in 2018 used careful phrasing to describe how two universities skirted Federal regulations:2

existing equipment can be used for hemp production

existing equipment can be used for hemp production

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Annual Report on the Status and Progress of the Industrial Hemp Research Program (2018)

Advocates for legalizing marijuana often note the George Washington grew hemp. Mount Vernon acknowledges that, and started growing hemp at the plantation in 2018. Both Montpelier and Mount Vernon partnered with the University of Virginia's industrial hemp research program, which provided the legal authority to cultivate hemp for the education of tourists.

George Washington grew hemp for the fiber, not for smoking to obtain the psychoactive "high" from tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). In his time, hemp seed oil was also used like linseed oil from flax. Mount Vernon makes clear:3

Source: Mount Vernon

The legalization of marijuana as an agricultural product began when the US Congress passed the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, part of the Farm Bill that the US Congress reauthorizes every five years. The 2018 legislation redefined hemp as a legal agricultural product, but with a key threshold. Marijuana products with a concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) below 0.3% were "industrial hemp," and were removed from the definition of a Schedule 1 drug in the Controlled Substances Act.

Also in 2018, the Virginia General Assembly established a program which allowed farmers to grow industrial hemp without being associated with a university research program. Registration with the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services made hemp a legal crop. After passage of the state law in 2018, Industrial Hemp Grower Registrations authorized growing the crop in 55 Virginia jurisdictions, indicating the potential interest in the agricultural community.

The focus at the time was on producing the fiber in the stalk, and the potential use of the oil in the seeds for biodiesel.

The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services did not permit farmers to grow hemp in order to extract cannabidiol (CBD) and sell it for distribution to those without a state registration. The state initially was unwilling to allow the growers to produce CBD and supply the stores selling CBD-infused products.4

industrial hemp has a concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) below 0.3 percent, too low for users to get "high"

industrial hemp has a concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) below 0.3 percent, too low for users to get "high"

Source: Virginia Industrial Hemp Coalition, About Hemp

The Virginia Hemp Company sought to recruit hay farmers in 2018, getting them to grow hemp instead. It planned to use the best fiber for clothing and to press the remainder into "hempcrete," a substitute for concrete which could be used in building houses. There was no significant demand for fiber to be used for making rope, since nylon had filled that niche after World War II.

The company proposed building the state's first hemp processing plant in Mount Jackson; it speculated that there would be a demand for 30-50 fiber-producing plants within Virginia. A farmer in the Shenandoah Valley who had been growing hemp in association with James Madison University research commented:5

That initiative failed to thrive and the plant did not open as planned in 2019, but later that year 2019 Shenandoah Valley Hemp received approval from the Elkton Town Council to open its processing plant. The company, organized initially by five brothers who grew a crop of hemp in 2019, advertised sale of cannabidiol (CBD) oils, Smokeable Hemp Flower and Hemp Fiber.

Their market advantage was to be a transparent vertically integrated "seed to sale" company, with testing to show the purity of their product. The company, renamed Pure Shenandoah, committed to purchase 100% of its raw hemp from Virginia growers. It became the first industrial hemp processor authorized by the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services to use the "Virginia’s Finest" trademark, which had previously been applied just to food products which included hemp.

Rockingham County matched the grant of $50,000 from the Governor's Agriculture and Forestry Industries Development Fund. The mayor of Elkton welcomed a business that invested over $3 million in its local processing plant, saying it:6

industrial hemp, shown 40 days after planting, can be grown to produce cannabidiol (CBD) or fiber

industrial hemp, shown 40 days after planting, can be grown to produce cannabidiol (CBD) or fiber

Source: Pure Shenandoah, About

After the US Congress passed the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 and removed hemp from the list of federally controlled substances, states were allowed to license farmers who planned to grow hemp. The Federal legislation authorized sale of hemp and its byproducts.

Hemp could be grown for fiber and grain, but also for cannabidiol (CBD) - so long as the plant always contained less than 0.3% of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The measure of "too much" was based on exceeding 0.3% of Delta-9-THC.

growing and processing industrial hemp is now legal in Virginia

growing and processing industrial hemp is now legal in Virginia

Source: Code of Virginia, Title 3.2. Agriculture, Animal Care, and Food » Subtitle III. Production and Sale of Agricultural Products » Chapter 41.1. Industrial Hemp

After passage of the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, a product containing cannabinoid (CBD) derived from licensed hemp growers and processed consistent with all state and Federal regulations was no longer classified as a Schedule I substance. It was legal for a state-licensed farmer in Botetourt County to grow the product desired by LilyHemp Boutique and Gourmet, which processed hemp and sold CBD-infused products at its store in Vinton and online.

Green Valley Nutrition was the first private company in Virginia to begin processing hemp for CBD, starting in 2018. It contracted with Albemarle Hemp Company and Pure Shenandoah to help them get started in the hemp industry.7

sale of CBD-infused products derived from industrial hemp growers were legalized in 2018

sale of CBD-infused products derived from industrial hemp growers were legalized in 2018

Source: LilyHemp Boutique and Gourmet, Shop Lilyhemp

The law did not grant a blanket authorization for all products with cannabidiol (CBD). Products made from marijuana provided by unlicensed growers were still illegal. Many CBD-infused products sold in retail outlets remained illegal in the eyes of the Drug Enforcement Administration. However, with confusing laws and regulations, action by law enforcement agencies was rare.

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 allowed hemp growers to buy crop insurance, and for processors to ship cannabidiol-infused items through the US Postal Service. The US Department of Agriculture announced before the 2020 crop was planted that hemp growers could qualify for Multi-Peril Crop Insurance.

At least 20 acres had to be planted for fiber and grain, or five acres if the hemp was planted to produce cannabidiol (CBD). Insurance required having a history of production the previous year, so first-time growers could not quality. Insurance payments for 55% of the market price would be paid if crop losses exceeded 50% of expected production. Farmers had to have signed a crop sale contract prior to a March 16, 2020 deadline, which also limited potential use of the insurance program. The insurance addressed weather-based risks, but no payments would be paid for hemp where the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) level was higher that 0.3%.

After 2018, banks and other businesses in the financial services industry could loan money to hemp farmers, and could process credit card transactions for purchase of products with cannabidiol - so long as the threshold of 0.3% of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) was not breached.

Because recreational marijuana use remained a violation of Federal law, banks were not authorized to deal with companies that were operating legitimate recreational marijuana businesses in states which had authorized its use. Attempts in the US Congress to permit banks to deal with businesses that were legal under sate law failed consistently, starting in 2019.

Legalization created a challenge for state officials. Virginia State Police had a laboratory test to determine if marijuana has a tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration below 0.3%, but no field test that could distinguish industrial from intoxicating hemp.

If a person with a grower, dealer, or processor registration was caught with marijuana, it could be sent to a lab for testing. If the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration exceeded 0.3%, the person could be charged with drug possession. A person without a registration for either medical marijuana or for growing/dealing/processing industrial hemp could not assert an "affirmative defense" to avoid punishment for drug possession.8

In 2021, the US Department of Agriculture approved the "Plan to Regulate Hemp Production in the Commonwealth," as prepared by the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS). The USDA Risk Management Agency offered Whole-Farm Revenue Protection for industrial hemp starting with the 2020 crop year. Crop insurance was limited to coverage of hemp grown for fiber, flower or seeds; hemp with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) above the compliance level did not qualify.9

Entrepreneurs discovered they could process hemp to create products with Delta-8-THC, a version of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) not constrained by Federal or Virginia laws even though it was intoxicating. Stores began to sell "gummies" and buds sprayed with Delta-8 that had been chemically synthesized from cannabidiol (CBD). Items could include enough Delta-8 to create a psychoactive effect comparable to ingesting or smoking products with an illegal level (greater than 0.3%) of Delta-9.

In November, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that it did not consider cannabidiol to be "generally recognized as safe" as a dietary supplement for use in human or animal food. Products infused with cannabidiol were not legal to sell, in the eyes of the Federal agency. There was no announcement of any effort to interfere with sales, however, and the unregulated marketplace continued after the announcement.

Even without acceptance of health claims for cannabidiol products by the Food and Drug Administration, the hemp market was expected to grow dramatically. As one observer noted:10

industrial hemp is valued for both its fiber and its oil

industrial hemp is valued for both its fiber and its oil

Source: Appalachian Biomass Processing, Fiber Hemp Info

As the legal hurdles for growing hemp for fiber were simplified, 1,183 growers, 262 dealers and 117 processors got industrial hemp licenses from the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. The farmers registered 2,200 acres for growing the new crop. In 2018, the state had approved 85 grower permits.

Tobacco farmers were encouraged to grow just a few acres the first year. They had the drying barns and other equipment needed to prevent mold from growing on the hemp, plus farm workers who knew how to cut the plants and place them on racks for a month of drying out.

There was no track record for calculating the costs to grow and process hemp, and estimate potential profits. To minimize the economic risk, Cooperative Extension agents advised planting small areas rather a high percentage of the farmland.

The best way to dry the hemp was unknown in 2019. Late that year, a Christiansburg entrepreneur developed a drying kiln using infrared heat to dry the plants, and claimed the low heat would preserve the valuable cannabidiol (CBD) desired by processors.

One risk was that storage before sale could result in the hemp exceeding the 0.3% cannabidiol (CBD) threshold. Farmers who planned to store hemp until processors offered higher prices the following Spring were at risk of the THC-A naturally converting *after harvest* into THC-C. If the final U.S. Department of Agriculture regulations calculated the 0.3% threshold at time of sale rather than time of harvest, then the stockpiled crop could become worthless.11

industrial hemp, shown 40 days after planting, can be grown to produce cannabidiol (CBD) or fiber

industrial hemp, shown 40 days after planting, can be grown to produce cannabidiol (CBD) or fiber

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Annual Report on the Status and Progress of the Industrial Hemp Research Program (2017)

Initially, most farmers planned to ship their hemp to out-of-state processors who would make cannabidiol (CBD) from the oil-rich seeds. That oil could also be used as a cooking oil and in salad dressing, while the hulls from the seeds ("hemp hearts") could be added to granola and animal feed.

Special effort was required to manage the buds and clip the apical meristem in order to produce "smokable flower" with less than 0.3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). If buds were trimmed too late, they could go to seed. The simplest growing process was to produce for fiber rather than products based on the oils, terpenes, and other natural chemicals in the marijuana plants.

Hay farmers in the Shenandoah Valley who adopted the new crop anticipated there would be a local facility for processing hemp into final products. Shipping hemp stalks to the closest fiber-production facility, which in 2019 was in Louisville, Kentucky, was too expensive. The Virginia Hemp Company had proposed building a facility in Mount Jackson to produce fiber for textiles and hempcrete, but farmers discovered in 2019 that the market demand for cannabidiol (CBD) was greater than for fiber.12

mature hemp plants ready to harvest for fiber, before World War I

mature hemp plants ready to harvest for fiber, before World War I

Source: Bureau of Plant Industry, US Department of Agriculture, Circular No. 41 (1908-1913)

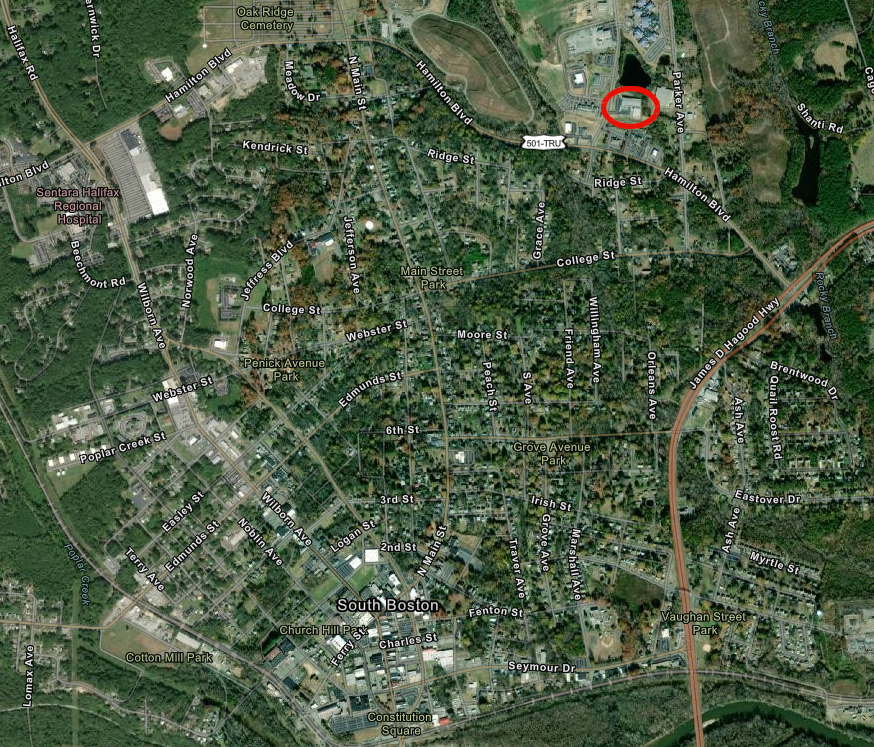

The entrepreneurial opportunity to "get in early" in the hemp business created more proposals that actual processing facilities. Investors announced plans for another hemp processing plant in Halifax County in late 2019. The county's Industrial Development Authority obtained a $250,000 grant from the Virginia Tobacco Commission to subsidize construction of a $6.35 million "Project Phoenix" facility. The name of the company planning to invest $1.9 million and hire over 40 workers was not identified publicly at the time when the grant was approved, because negotiations were underway to obtain more incentives from the Virginia Economic Development Partnership and the Virginia Department of Agriculture Consumer Services.

In the first three years of operation, investors claimed the plant could purchase to purchase $50 million in hemp from farmers in the area. The processing facility investors projected that 68 farmers would each grow, on average, 15 acres of hemp. That would require the farmers to spend $2 million to grow 1,000 acres of hemp, so the processing facility would involve a substantial local commitment beyond the grant from the Virginia Tobacco Commission.

When the Halifax County Board of Supervisors and Industrial Development Authority finally guaranteed a $2.6 million loan and accepted the grant from the Tobacco Region Revitalization Commission in May, 2020, the number of expected jobs was just half of what had been originally discussed. Blue Ribbon Extraction projected it would hire 22 people to process six million pounds of hemp annually, at full production.

Governor Ralph Northam cut a ribbon when the cannabinoid oil (CBD) extraction plant opened in October, 2020. The company, renamed Golden Piedmont Labs, aimed to make Southside Virginia the hemp industry equivalent to Napa Valley's status in the wine industry. Agricultural hemp lacked the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) which provided a "high" experience, but the health effects of cannabidiol (CBD) could be obtained via a gummy, capsule, topical cream, lotion, or tincture. The perception that CBD was a magical elixir which cured everything from insomnia to heart disease created a surge in demand.

in October, 2020, Golden Piedmont Labs opened its cannabinoid oil (CBD) extraction plant in South Boston (Halifax County)

in October, 2020, Golden Piedmont Labs opened its cannabinoid oil (CBD) extraction plant in South Boston (Halifax County)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The need for new processing facilities for the new crop was clear. In 2019, the only hemp processor near Halifax County was in Oxford, North Carolina, and that facility was unable to handle more product. A processing plant would stimulate agriculture in Southside Virginia where tobacco was once king:13

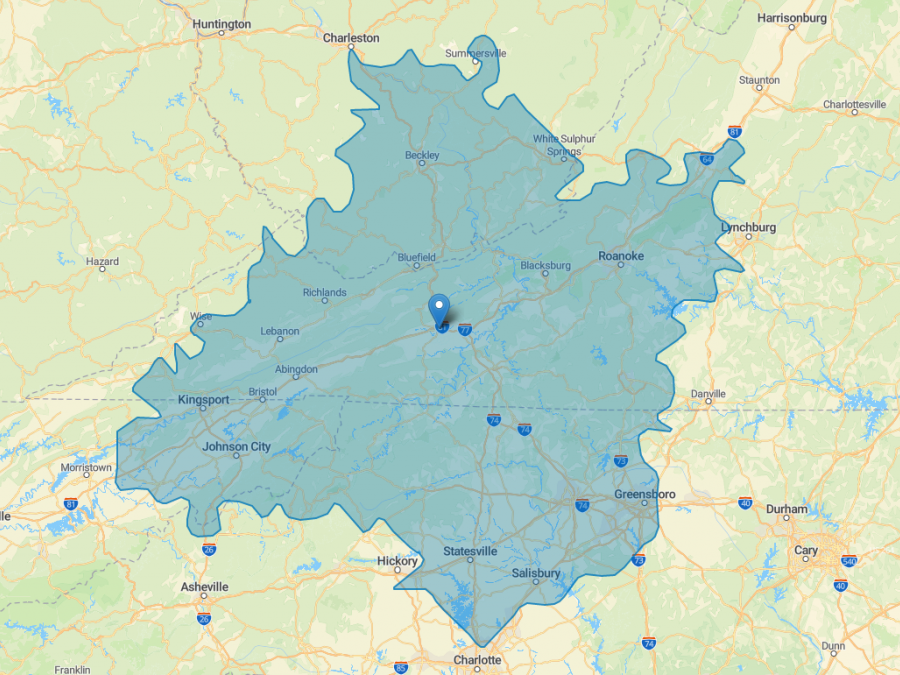

However, Gov. Ralph Northam's first Economic Development announcement for a commercial processing facility was in Wythe County. Appalachian Biomass Processing announced plans to purchase hemp from 4,000 acres being farmed within a 2.5 hour drive from the plant. Processing would "decortify" the plant stalks into bast fiber (used by textile companies to make fabrics) and hurd (made into high-absorbency animal bedding). Farmers seeking to sell their crop to Appalachian Biomass Processing would need to grow tall plants with long fibers, rather than focus on growing flowers for production of cannabidiol (CBD).

A representative of the customer for the hurd product said it had been importing hemp from Europe, and:14

The chair of the Wythe County Board of Supervisors used the governor's visit to make a bold claim for his community:15

Appalachian Biomass Processing in Wythe County planned to source hemp from farms within a 2.5 hour drive

Appalachian Biomass Processing in Wythe County planned to source hemp from farms within a 2.5 hour drive

Source: Appalachian Biomass Processing, Sell To Us

The 2019 crop was planted before farmers could identify who would purchase their hemp. Processing plants required time to finance and build, and the shortage of such facilities affected the price of the hemp. Illinois farmers discovered at the end of the season that processors wanted to purchase 5,000 pounds at a time. Farmers guesstimated they would harvest 2,000 to 12,000 pounds per acre, but many had been experimenting for their first year on small plots.

Farmers had to decide at the seed selection stage if they planned to grow hemp for fiber or for cannabidiol (CBD). Tall and slender plants for fiber could be planted with a drill and harvested with a combine, similar to wheat. Plants grown for cannabidiol (CBD) were planted three-six feet apart, and labor-intensive to grow. They were harvested before the CBD-rich flowers were pollinated and cannabidiol (CBD) levels dropped during seed production.

Only female plants were desired by farmers growing for the flowers; for them, male plants that led to seed production were a problem. A farmer who planted feminized seed (costing $1 per individual seed) or cuttings from female plants (costing $4-$7 per cutting) wanted to isolate that field from others where male as well as female plants were planted for a fiber crop. If pollen drifted over, hemp flowers would stop concentrating cannabidiol (CBD) as seeds developed.16

A farmer in Rappahannock County who planted 1/4 acre described herself as a "hempster." She grew 220 plants, drying them after harvest from rafters in a converted garage. She said in late 2019, after her processor backed out from collecting her harvest because their capacity was overloaded:17

Across the nation, farmers got licenses to plant 400% more acres in hemp in 2019 compared to 2018. An additional 13 states issued licenses, beyond the 21 states in 2018. Only New Hampshire, Mississippi, South Dakota, and Idaho authorized no industrial hemp. 90% of the crop was expected to be processed to obtain cannabidiol (CBD), rather seek the fiber as the primary product. That contrasts with hemp production in colonial Virginia, when the relatively strong and mildew-resistant fibers were desired for manufacture of rope.18

hemp fibers are preferred for production of rope, because they are stronger than cotton and more resistant to mildew

hemp fibers are preferred for production of rope, because they are stronger than cotton and more resistant to mildew

Source: Wikipedia Commons, Textile

The mis-match between supply and the ability to process the harvested crop led to a 50% drop in the price of hemp in Illinois near the end of the season. In Kentucky, in mid-2019 farmers were able to sell their hemp at $4.35 for each percent of CBD in each pound of hemp. That price dropped to less than a dollar by December. Farmers had to consider the marginal cost of harvesting and drying their hemp vs. letting their first crop just rot in the fields.19

Across Virginia, 1,183 industrial hemp growers planted 2,200 acres of hemp in 2019. On the 16 acres in Pittsylvania County, the early adopters of the new crop planned to grow hemp that would contain 6-10% cannabidiol (CBD) but less than 0.3% of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Because there was no standardized testing methodology to assess progress through the growing season, 2019 was an experimental year. The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services tested crops grown by 75 farmers, and destroyed 18% of the tested crops because they exceeded the 0.3% limit.20

There was no historical track record to guide which farming practices would be most appropriate on different soils. One Pittsylvania County farmer commented:21

hemp flowers and seeds produce tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)

hemp flowers and seeds produce tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Annual Report on the Status and Progress of the Industrial Hemp Research Program (2018)

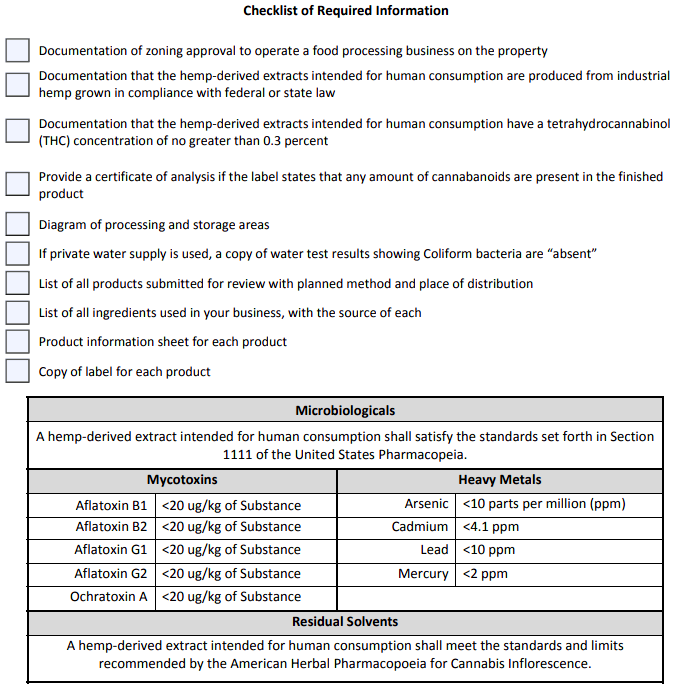

One challenge was to ensure safety of the cannabidiol (CBD) product intended for human consumption. The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services required Registered Industrial Hemp Processors to treat it as a food additive to be produced under food safety inspection regulations, such as an inspection of the processing facility prior to starting the "food operation."22

food with hemp can qualify to use the Virginia Finest trademark of the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services

food with hemp can qualify to use the Virginia Finest trademark of the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services

Source: SunnySnacks, PB(Hemp)Cup BubbyBalls

Securing the hemp crop was an issue as soon as the 2019 crop was ripe. In Smyth County, an 18-year old and a 20-year old were caught stealing industrial hemp. When arrested, they had two trash bags packed with hemp plants, but local officials suspected they were part of a larger operation.

Potential marijuana buyers would have recognized they were purchasing Cannabis sativa, but without a complicated laboratory test they would not have known initially that the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration in the industrial hemp was below 0.3%. Marijuana sold before the 1990's typically had 2% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but by 2019 some strains bred for high psychoactive impacts had concentrations of almost 30%. Smoking look-alike industrial hemp, with high CBD concentration and low THC, would not create an equivalent recreational "high."

To improve profitability in 2020, the Virginia Industrial Hemp Coalition pressed for the state to raise the 0.3% limit on THC content to 1%. That would reduce the risk that a crop would have to be destroyed because it exceeded the threshold, but industrial hemp with just 1% THC would not be marketable for recreational use.

By 2023, there were 266 farmers growing industrial hemp and 116 registered processors converting it into rope, building materials and animal bedding. Of the 662 acres planted, 148 acres ended up being harvested.

Another attempt to raise the THC threshold to 1% failed in the 2024 General Assembly. Farmers harvested hemp before the flowers bloomed in order to reduce the THC percentage, but that timing limited the varieties of hemp that could be grown in Virginia. The president of the Virginia Hemp Coalition said:23

the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services required cannabidiol (CBD) producers to meet requirements for producing a food additive for human consumption

the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services required cannabidiol (CBD) producers to meet requirements for producing a food additive for human consumption

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Manufacturer of an Industrial Hemp‐Derived Extract Intended for Human Consumption

Theft of hemp plants was also a problem in Dinwiddie County, but at harvest a new issue developed. Residents in the Lake Jordan subdivision complained that the "skunk-like" smell generated during the cutting of the hemp plants was so repulsive that some people were considering moving away. Though the plants lacked high levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), they still contained the chemicals which produced the standard marijuana smell.

One mother expressed her special concerns about the odor permeating the neighborhood:24

The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services reported that more than 1,300 growers officially registered in 2019 as growers of industrial hemp. That year, they planted 2,200 acres of hemp.

warm season grasses outcompete hemp, but in 2018 Virginia State University established a good stand in Augusta County

warm season grasses outcompete hemp, but in 2018 Virginia State University established a good stand in Augusta County

Source: Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Annual Report on the Status and Progress of the Industrial Hemp Research Program (2018)

For 2020, some hemp farmers chose to become more vertically integrated and start processing the product on their own farm. TruHarvest Farms in Montgomery County, the largest Virginia producer in 2019, planned to add 15 acres in 2020 to its 85 acres of hemp fields grown in 2019. It built a 30,000 square foot greenhouse for propagating the plants. It also planned to create creams and items for oral consumption from its crop, developing as a farm-to-table operation.

The value of the hemp was demonstrated in 2021 - someone stole harvested buds worth almost $300,000 from the TruHarvest barn. The buds, which could be processed to created cannabidiol (CBD), were in one-pound boxes worth $2,500 each.

A seasonal farmhand was convicted of the crime, though the hemp was never recovered. Prosecutors speculated that he sold it to a marijuana dealer in Indiana, who mixed it with other marijuana to "bulk up" the product he was selling for recreational use.25

After just one or two growing seasons, some farmers discovered that hemp was not a profitable crop. Garrett Farms in Roanoke County put 1,700 hemp plants into the ground on three acres in 2019 and lined up four processors, anticipating they would pay $50 a pound in a competitive auction to purchase the crop. The over-supply of hemp drove the price down to as low as 23 cents a pound. The 1,000 pounds of hemp was never sold, and the farm pivoted to agritourism where visitors were each given a hemp plant.

The Rappahannock Hemp Cooperative provided mutual support in Rappahannock County, evolving eventually into the non-profit Rappahannock Hemp Collective. One member concluded that he could use farm dogs to minimize deer grazing damage and harvest before budworms infested the hemp, but just growing the crop was not worth the effort:26

Some hemp farmers chose to become more vertically integrated. In the City of Chesapeake, the owners of Seva Farms grew 6,000 hemp plants in 2020 and sent the crop to Oregon for processing. In 2021, they got approval from the city council to open a processing facility in the Greenbrier Industrial Park where extraction equipment could produce CBD products. Growing hemp was transitioning from an experiment into a standard farm product, with all the risks associated with weather, disease and markets and with regulatory controls that farmers could accept.27

Supply and demand shaped the market for cannabidiol (CBD) products. Golden Piedmont Labs in Halifax County became the largest hemp processor in Virginia. Its high-cost equipment capable of extracting CBD created a high-quality product that earned it the CBD Wholesaler of the Year award, but the company was not profitable in 2022.

Some farmers who grew hemp found they could not sell the crop, or get paid by processors. An extension agent for the Halifax Virginia Cooperative Extension office outlined the basic economics problem:28

TruHarvest Farms in Montgomery County was Virginia's largest industrial hemp farm in 2019, growing 85 acres

TruHarvest Farms in Montgomery County was Virginia's largest industrial hemp farm in 2019, growing 85 acres

Source: TruHarvest Farms, Gallery

By 2024, the market for agricultural hemp had collapsed. Sales of cannabidiol (CBD) products were limited by state regulations and a ban on products with synthetic Delta-8 and Delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The 2,205 acres planted in 2020 dropped to 660 acres in 2023. The 1,200 industrial hemp growers registered with the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services in 2020 dropped to 159.

A 2024 story in Cardinal News reported:29

Revisions in November 2024 to the 2018 Farm Bill added a major deterrent to growing agricultural hemp. The new Federal legislation essentially banned extraction of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and concentrating/processing it for sale in Delta-8 and Delta-10 products, so the demand for hemp would be substantially reduced. Customers such as Bingo Beer in Richmond would no longer by hemp products from producers such as Pure Shenandoah.

The new law was scheduled to go into effect in November 2026. That gave enough time for farmers to plant something other than hemp in 2026.30

A market remains for industrial hemp, separate from manufacturing products with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The seeds are valued in food production, including protein bars:31

In December 2025, President Trump ordered Federal agencies to reclassify marijuana from a Schedule I1 to a Schedule III drug under the Controlled Substance Act. The Bidden Administration had started that process in 2024.

Reclassification, when completed by the Drug Enforcement Agency, would not not legalize recreational use but would expand opportunities for research. It would also change how state-licensed businesses deduct expenses on Federal taxes under Internal Revenue Code Section 280E, and facilitate banking and interstate transport of products.

Even without Federal legalization, reclassification was expected to expand the market and stimulate farming hemp, both outdoors and indoors, for use in products infused with cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).32