Virginia has a state court system which is separate from the Federal courts. Cases involving laws passed by the General Assembly are heard in state courts, and cases involving laws passed by the US Congress are heard in Federal courts. Laws, rules of procedure, and precedents are different in the state and Federal systems. At times, when an action could be treated as a violation of either Federal or state law, lawyers choose the system in which they wish to file a case.

The American Revolution transformed Virginia's judiciary from its colonial pattern. The current division of Virginia's executive, judicial, and legislative responsibilities into three separate branches did not occur until 1776. Virginia's first constitution in 1776 separated the judicial functions from the executive and legislative branches, except at the county court level. The roles of the Governor's Council were distributed to a State Senate, a Council of State to advise the governor, and an independent system of courts.

The 1776 Constitution of Virginia prohibited members of one branch of government from holding offices in another branch, except the local justices of the peace were allowed to serve in the General Assembly.1

The state constitution continued the colonial pattern where the governor appointed all the justices of the peace to serve on all county courts, and on the equivalent "hustings" and "corporation" courts in towns and cities. The county/hustings/corporation courts continued until 1904, when Circuit Courts absorbed their responsibilities.

The constitution gave to the General Assembly the authority to appoint other judges:2

The two Houses of Assembly shall, by joint ballot, appoint Judges of the Supreme Court of Appeals, and General Court, Judges in Chancery, Judges of Admiralty, Secretary, and the Attorney-General...

In October 1776, the General Assembly create a Court of Admiralty and appointed three judges. It managed the award of prize money for ships captured by captains sailing with a "letter of marque," a document issued by the state government which authorized private vessels to seize enemy ships. Vessels ("prizes") that were brought to a Virginia port by privateers with a letter of marque were sold in an auction managed by the Admiralty Court. Revenue from the auction was distributed according to a formula established by the General Assembly.

Virginia's Court of Admiralty was abolished in 1789. Under the new Constitution, the Federal government was given control over nearly all admiralty cases. No special Admiralty Court was created; Federal Circuit Courts were assigned responsibility for trying cases of piracy and others where admiralty rules of procedure apply.

Even today, admiralty law is used in resolving lawsuits brought for actions on navigable waters within Virginia. If a container ship hits a sailboat on the Chesapeake Bay, or a jet ski hits a pontoon boat on Smith Mountain Lake, the Federal Circuit Court will apply the Supplemental Admiralty Rules if there is any conflict with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.3

In October 1777, the General Assembly found time to re-establish the General Court. It served as an appeals court for cases tried in the county courts. It also had broad "original jurisdiction;" lawyers could bring cases directly to the General Court.

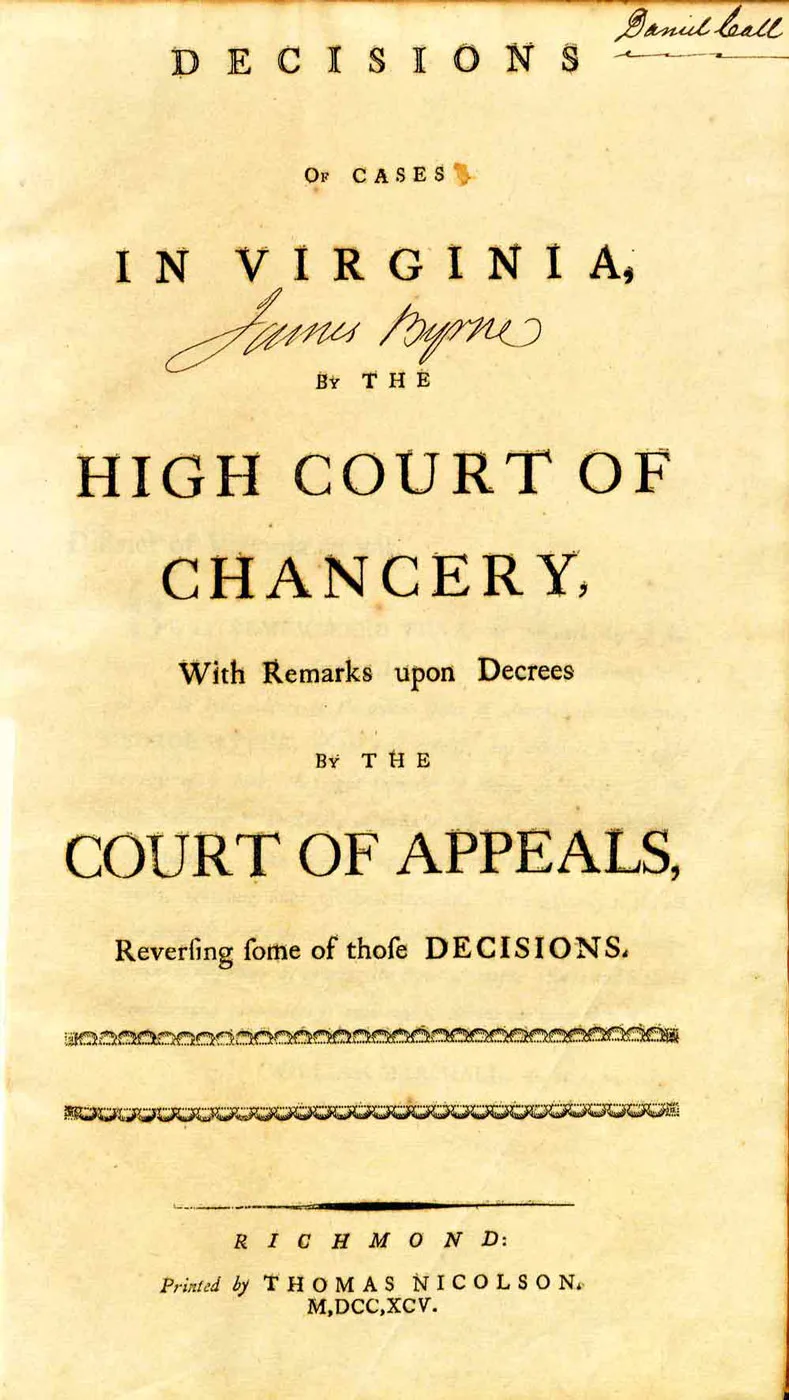

Also in 1777 the General Assembly created the High Court of Chancery. Until 1802 it handled all "chancery" cases, those requiring a judge to make an equitable decision based on fairness and common-sense principles, such as interpretation of how to distribute assets in the estate of a deceased person, rather than to make a decision based on pre-existing law. In 1803 the High Court of Chancery was replaced by three Superior Courts of Chancery, with court held in Staunton, Richmond and Williamsburg.

The General Assembly continued to expand the number of chancery courts to speed cases through the judicial process by adding three more chancery courts in 1812 and another three in 1814. Finally in 1830, the nine Superior Courts of Chancery were abolished and their jurisdiction transferred to a Circuit Superior Court of Law and Chancery, with one in every county.

three Superior Courts of Chancery replaced the High Court of Chancery in 1803

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

Responsibility for handling appeals of civil and criminal cases was divided in 1779 when the Court of Appeals met for the first time. It was granted authority as the final appeals court for civil cases. The legislature appointed members of the Admiralty Court, General Court, and the High Court of Chancery to serve as the judges on the Court of Appeals.

The General Assembly changed the membership of the Court of Appeals in 1788, since the Court of Admiralty was abolished. The legislature began electing five separate judges and granted them life terms. The increased independence of the judges, with life terms, mimicked the approach used in the US Constitution for the new Federal government's Supreme Court. The number of judges on the Court of Appeals was reduced from five to three in 1807, then back to five in 1811.

When Edmund Pendleton was appointed to the Court of Appeals, he resigned from the High Court of Chancery. George Wythe ended up as the only member the High Court of Chancery, and in 1792 the General Assembly passed a law that the court would have just one judge. As President of the Court of Appeals, Wythe's professional rival Edmund Pendleton was able to overturn decisions made by the High Court of Chancery.

The workload and responsibilities for the General Court were also modified by the creation of 18 District Courts in 1789. The District Courts handled initial appeals from the county courts, and decisions by District Courts could be appealed to the Supreme Court of Appeals. The 18 District Courts were replaced by Superior Courts of Law in 1808. Each county held a Superior Court of Law meeting that processed civil and criminal cases, presided over by a General Court judge who would "ride circuit." The District Courts and then the Superior Courts of Law met twice each year, so General Court judges were constantly on the move.

Jurisdiction over chancery cases was consolidated with civil and criminal cases in the 1830 state constitution. The Superior Courts of Law in each county and the three three Superior Courts of Chancery were replaced by a single Circuit Superior Court of Law and Chancery. The Circuit Superior Court of Law and Chancery met in each county. The Court of Appeals was renamed the Supreme Court of Appeals.4

George Wythe wrote a book to articulate his legal reasonings which the Court of Appeals had rejected

Source: Colonial Williamsburg, Wythe 102

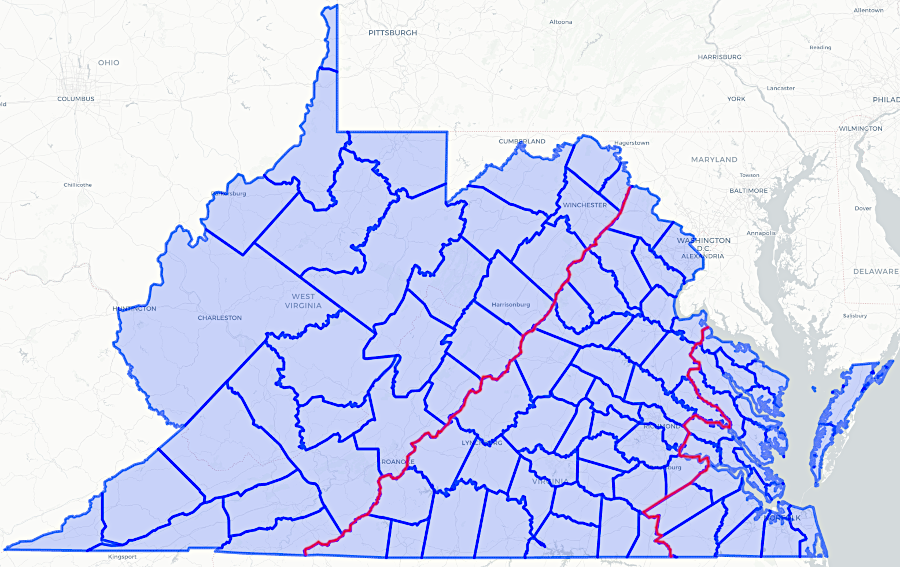

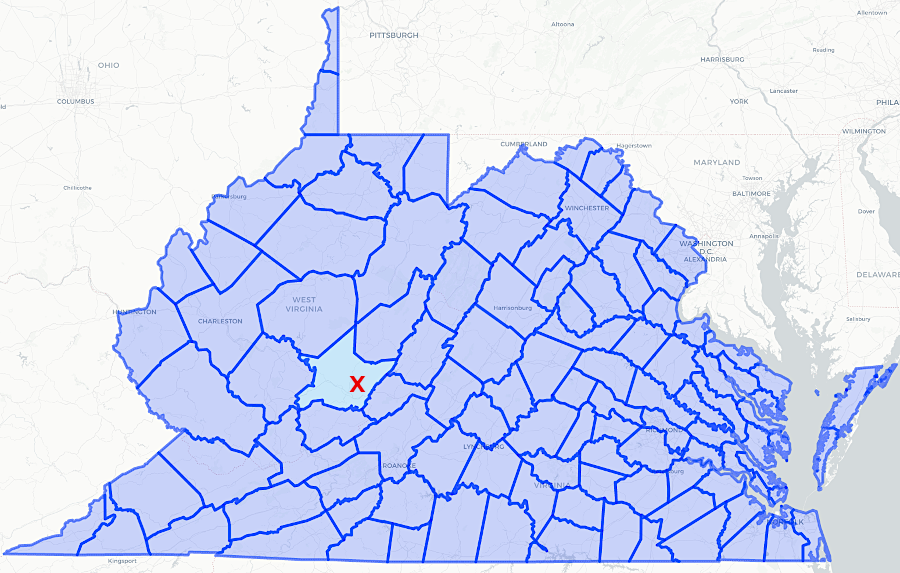

Settlers west of the Blue Ridge were able to force a revision of the state constitution in 1830, but failed in their effort to get judges elected rather than appointed to life terms by a General Assembly dominated by the Tidewater aristocracy. In a small gesture to make the judiciary more responsive to people living west of the mountains, the Supreme Court of Appeals was required to meet one a year west of the Blue Ridge. It chose to gather at Lewisburg.

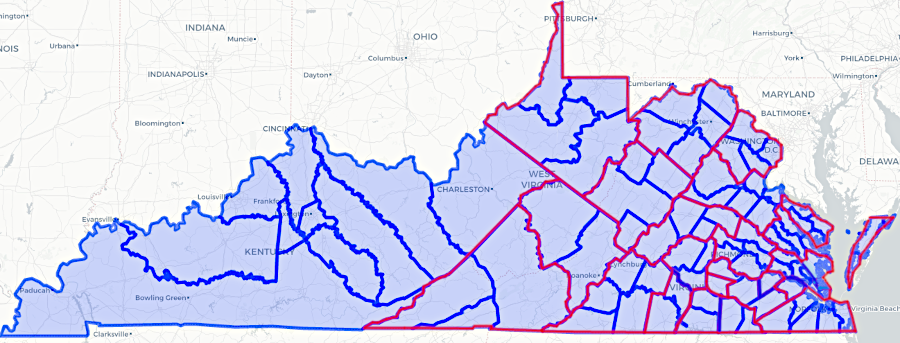

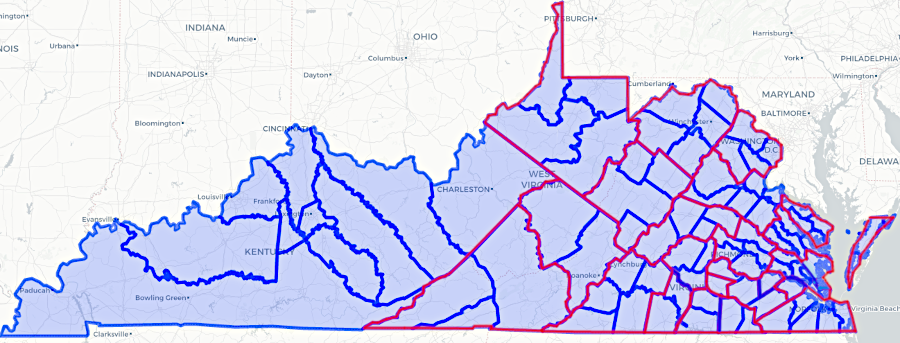

starting in 1831, the Supreme Court of Appeals started to meet west of the Blue Ridge (yellow line) at Lewisburg in Greenbrier County

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

The expanded workload of the Court of Appeals was too great for the five judges to handle all the cases. In 1832, the legislature authorized creation of a Special Court of Appeals, when needed. Judges on the General Court, rather than legislators, chose the judges who would be tasked to process the excess cases. The first Special Court of Appeals was created in 1848.

Support for expanding the capacity of the renamed "Supreme Court of Appeals" was not linked to any commitments by new judges to uphold the legislators' preferred interpretation of the laws. Virginia's judges began to establish their independence from the legislature quickly. In 1782, the Supreme Court of Appeals explored whether it had the authority to declare an act passed by the General Assembly to be unconstitutional. Judicial review by judges was a new concept at the time, long before John Marshall arranged for the US Supreme Court to declare an act of the US Congress to be unconstitutional.

In 1782, the Supreme Court of Appeals avoided claiming that it had the power to block a law passed by the General Assembly, by declaring in the Commonwealth v. Caton case that the particular act was constitutional. In his ruling, George Wythe chose to justify judicial review anyway. He was blunt in telling the legislature that it could act only within the limits granted in the state's 1776 constitution:5

- I, in administering the public justice of the country, will meet the united powers at my seat in this tribunal; and, pointing to the constitution, will say to them, here is the limit of your authority, and hither shall you

go and no further.

The 1851 state constitution revamped the judiciary again. The responsibilities of county/hustings/corporation courts were not modified, but the governor lost the power to appoint members. The 1851 constitution specified that each county was to be divided into districts with equal population and territory, that each district was to elect four Justices of the Peace to serve four-year terms, and that court sessions typically would require participation by three-five justices. Local voters also gained the power to elect the local Clerk of the Court, Commonwealth's Attorney, Sheriff, and other local officials previously appointed by the governor.

The General Court was abolished, and the Supreme Court of Appeals was given its responsibility for appeals involving criminal cases. The General Assembly lost the ability to choose the Supreme Court of Appeals judges. Under the 1851 constitution, the five judges were elected by the voters to serve 12-year terms rather than be appointed for life by the legislators. The state was divided into five "sections," with each section of Virginia electing one judge to the Supreme Court of Appeals.

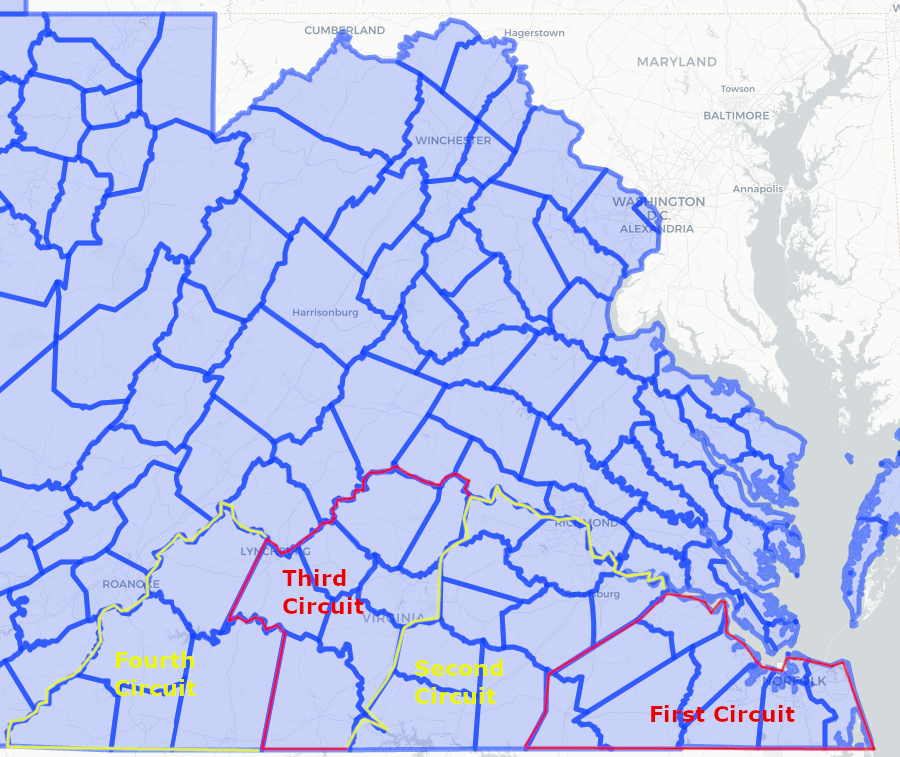

The Circuit Superior Courts of Law and Chancery, created in 1831, were abolished. They were replaced by 21 Circuit Courts and 10 District Courts. Circuit Court judges were elected by the voters for eight-year terms. The judge elected for each circuit had to hold court in each county/city at least twice a year.

District Courts were composed of at least three judges from the circuits within that district, plus the judge of the Supreme Court of Appeals elected from the section which included the district. Courts hearings required three-five judges elected from the circuits within the district, plus the elected Supreme Court of Appeals judge from the area. District Courts had to meet at least once each year somewhere within the district.

Boundaries of circuits, districts, and sections were defined initially in the 1851 state constitution, with the provision that after eight years the General Assembly could revise the boundaries.6

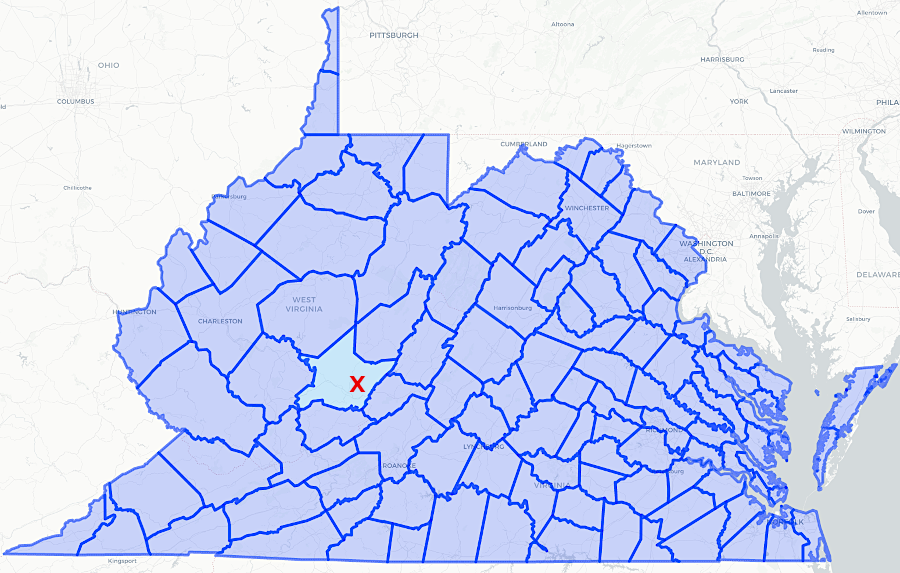

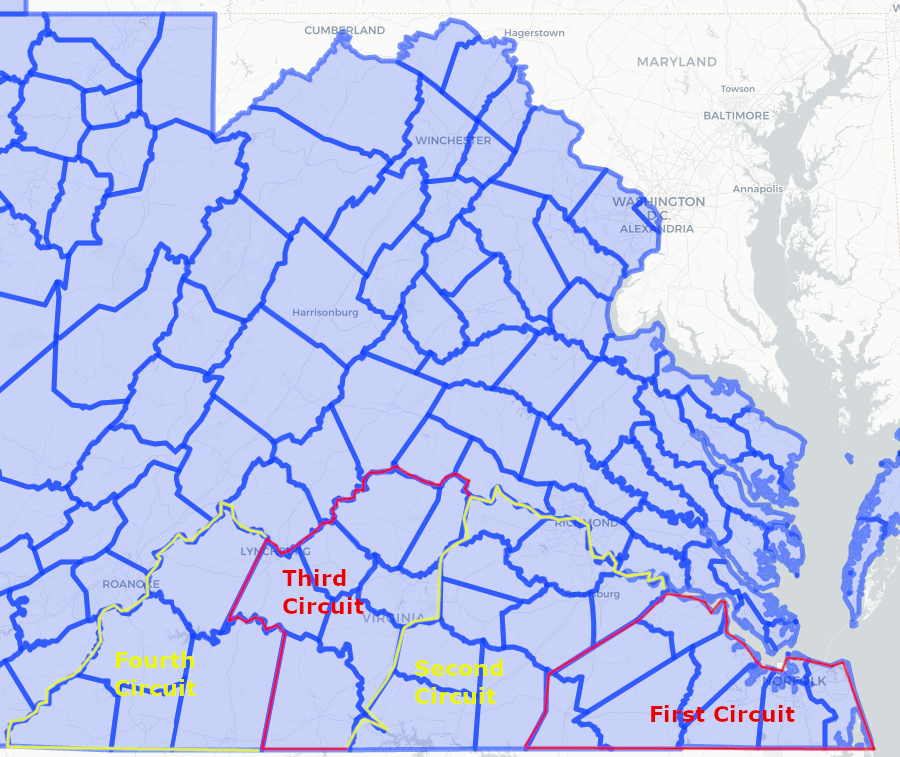

the 1851 constitution allowed voters to elect judges from 21 circuits, and voters within the First-Fourth Circuits also elected the First Section judge to the Supreme Court of Appeals

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

The 1864 constitution reduced the number of circuits to 16, since creation of West Virginia had reduced the territory of Virginia. It also eliminated the election of judges to the Supreme Court of Appeals, and reduced the number of judges on it from five to three.

In 1869, the commanding general of Military District 1 dismissed the three members of the Supreme Court of Appeals because of their previous support for the Confederate States of America. He appointed three new members, but their term of service was short since Virginia was readmitted to the Union in 1870.7

The 1870 state constitution expanded the Supreme Court of Appeals back to five judges. The General Assembly was empowered to choose those five judges to serve for 12-year terms, and to choose Circuit Court judges for 8-year terms. That ended, permanently, the direct election of circuit court judges by voters instead of legislators. The length of the term served by county court judges was defined as six years.

Since Lewisburg was now in West Virginia, the Supreme Court of Appeals began to meet annually west of the Blue Ridge at Staunton and Wytheville. It was meeting at Wytheville in 1894 when the court authorized attorney Belva A. Lockwood to practice in Virginia, in a 3-2 vote. There were five new judges when the court met in Richmond in 1895, however, and the new judges unanimously blocked her from qualifying to serve. Women were not permitted to argue cases in Virginia courts until 1920, the same year that women gained the right to vote.8

The 1902 constitution eliminated the county courts, and transferred their responsibilities to circuit courts. It also defined boundaries for 24 circuit courts.3

"Article VI - Judiciary Department," Constitution of Virginia, 1902, http://vagovernmentmatters.org/files/download/427/fullsize (last checked February 14, 2021)

In 1928, Robert R. Prentis was the chief justice of the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. He led the Prentis Commission that drafted amendments to the 1902 constitution. Voters approved expanding the Supreme Court of Appeals from five to seven judges. Prentis did not propose changing the long-standing requirement that judges must be elected by a majority vote of both houses of the General Assembly.

9

The General Assembly eliminated the role of the elected justice of the peace, the last remnant of county courts established in the 1620's, at the end of 1973. Justices of the peace were replaced by appointed magistrates plus General District Court judges chosen by the General Assembly.

Magistrates are citizens who receive specialized training. The chief magistrate in each of Virginia's 31 districts for Circuit Courts must be a member of the Virginia State Bar, but no magistrate may be a lawyer. They are granted the power to issue arrest warrants, summonses, search warrants, and subpoenas that require someone to appear in court. Magistrates also conduct bail hearings and determine how much bond will be required before releasing someone who has been arrested.

Magistrates are intended to be independent from the police, so they can serve to protect citizens from excessive enforcement and inappropriate arrests. Magistrates decline to issue a search warrant or arrest warrant, if they think a request from a police officer lacks "probable cause."

Originally magistrates were appointed to four-year terms by the Chief Judge of the Circuit Court. Starting in 2008, the Office of the Executive Secretary of the Supreme Court of Virginia became responsible for hiring and overseeing magistrates. Training standards and operational procedures were standardized across the state, and the fixed term of service was eliminated.

At least one magistrate is available either on duty or on call, 24 hours a days: 10

- The 6 magistrates in the city of Roanoke receive approximately 175 complaints every day, of which approximately 150 result in warrants, subpoenas, or orders.

General District Courts were created in 1973, as part of systemic changes that eliminated the role of justices of the peace. Judges for General District Courts are elected by the General Assembly to serve six-year terms. When there is a vacancy, Circuit Court judges appoint temporary General District Court judges. They serve until the Virginia legislature meets again and appoints permanent replacements. The legislators have, at times, failed to appoint the person chosen by the governor.

Judges make all decisions in General District Courts. Those courts are not a "court of record" authorized to conduct jury trials. Today:11

- There is a general district court in each city and county in Virginia. The general district court handles traffic violations, hears minor criminal cases known as misdemeanors, and conducts preliminary hearings for more serious criminal cases called felonies. General district courts have exclusive authority to hear civil cases with claims of $4,500 or less and share authority with the circuit courts to hear cases with claims between $4,500 and $25,000. Examples of civil cases are landlord and tenant disputes, contract disputes and personal injury actions.

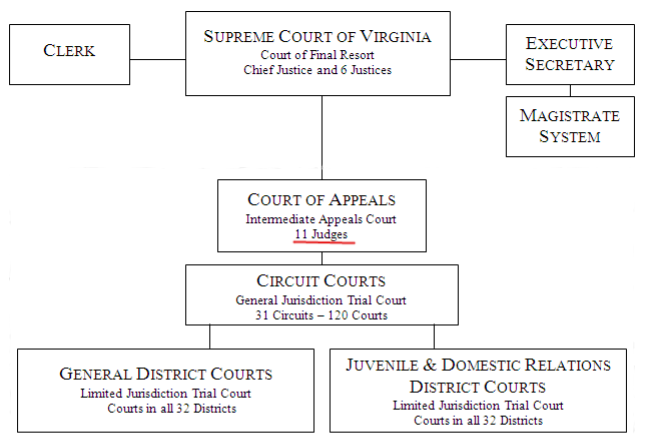

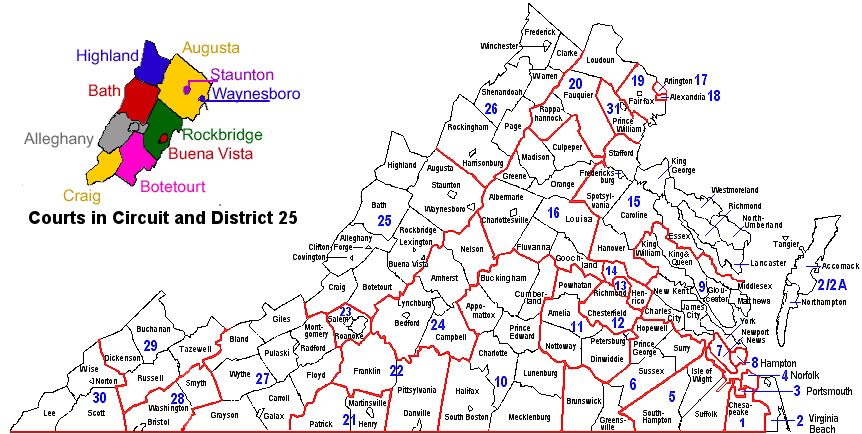

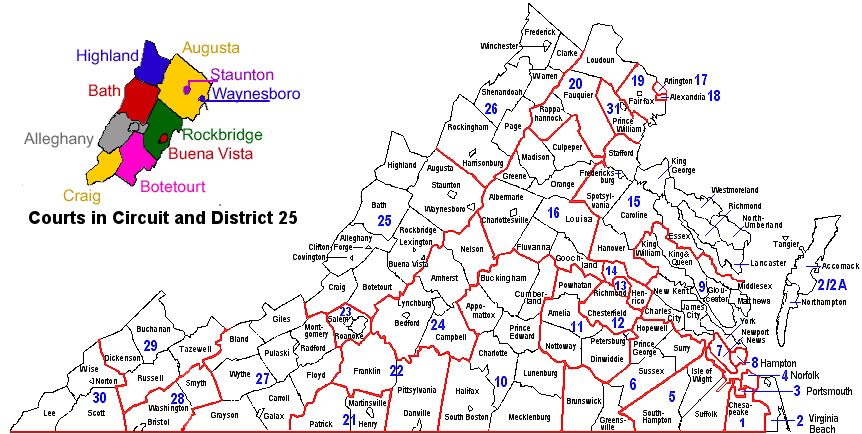

Virginia has 32 judicial districts, with a lower-level General District Court and a separate Juvenile & Domestic Relations Court serving each city and county plus 120 separate Circuit Courts

Source: Supreme Court of Virginia, Map of Virginia's Judicial Circuits and Districts

The General District Courts that hear all civil cases with "small claims" are located in different cities and counties. Plaintiffs can file claims against individual defendants in a jurisdiction where the "cause of action" occurred, where the defendant lives or works, or where the defendant has a business. Plaintiffs can sue corporations in a jurisdiction in which it has its principal office, or where the registered agent is located.

Judges in General District Court determine if someone has violated a traffic law, and determine punishment for those found guilty. In addition, the Virginia Division of Motor Vehicles (DMV) can assess "points" against a guilty driver through administrative action, separate from the court process.

Criminal cases in which a person is charged with a misdemeanor, with a penalty of no more than one year in jail and/or a fine of up to $2,500, are head in General District Court. General District Court judges also conduct preliminary hearings for more-serious felony cases, to determine if there is probable cause for a case to be sent to a grand jury. The General District Court judge can dismiss a case without probable cause, or forward to the grand jury. Only the grand jury can indict a defendant for a felony crime and forward the case to Circuit Court.

A defendant can appeal a decision from a General District Court to Circuit Court, and obtain a trial by jury if desired. In civil cases, if more than $20 is involved then a decision may be appealed to the Circuit Court.12

People under 18 years of age who are charged with a traffic violation appear in Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court. That court also hears cases involving custody, support and visitation of juveniles. Judges appoint a lawyer known as a guardian ad litem to represent the interest of a child.

The Commonwealth's Attorney may request that trials for those who are 14-17 years old at the time when they are charged with a felony offense be transferred to Circuit Court, where the juvenile may be tried as an adult. Traffic proceedings are retained until the juvenile reaches the age of 29. Records regarding most other cases involving juveniles in Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court are expunged when the person has reached the age of 19, and at least five years have passed after the last hearing.

Adults appear in Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court cases when charged with child abuse or neglect, or when spouses seek child support after a marriage separation. (Divorces are processed in Circuit Courts.) Similar to the General District Court, judges make all decisions. There no jury trials, and decisions can be appealed to Circuit Court.13

Jury trials are held in Virginia's 120 Circuit Courts. Each circuit has between 2-15 judges, depending upon the workload. The judges elect the Chief Judge of their circuit, but have no say in choosing the Clerk of the Court:14

- The clerk of the circuit court is a constitutional officer elected to an eight-year term by the voters of the locality. The clerk handles administrative matters for the court and also has authority to probate wills, grant administration of estates, and appoint guardians. The clerk is the custodian of the court's records, and the clerk's office is where deeds are recorded and marriage licenses issued.

The General Assembly elects Circuit Court judges to serve eight-year terms. Circuit Court judges also hear appeals from General District Court and some state administrative agencies.

Circuit Court judges preside over trials with juries. They also preside over trials without juries in civil cases when the parties are willing to trust the judge's judgment, and in criminal cases where both the defendant and Commonwealth's Attorney agree to waive a jury trial. Defendants are guaranteed a jury trial only if they plead guilty; those who plead "guilty" or "nolo contendere" get decisions from just a Circuit Court judge.

Circuit Court judges select the members of grand juries, which determine whether someone accused of a crime should have the charges dismissed or should be indicted and forced to stand trial. In addition to regular grand juries appointed at the start of each court session, judges may appoint special grand juries. They tend to draw attention, when a Commonwealth's Attorney seeks to investigate reported criminal activity by a government official or organization.

Grand juries never hear from the accused or their lawyers; they make their decision based on information exclusively from the prosecution. A grand jury's decision to indict is not equivalent to a determination of guilt, but only that there is sufficient evidence to justify holding a trial. A New York defense lawyer concerned that prosecutors had too much power over grand juries coined a phrase in 1979:15

- The district attorney could get the grand jury to indict a ham sandwich if he wanted to.

The 1971 amendments to the state constitution had renamed the top appeals court from Supreme Court of Appeals to the Supreme Court of Virginia, anticipating creation of a lower court to handle initial appeals from Circuit Courts. The amendments also the eliminated the option of creating a temporary Special Court of Appeals. Such courts had been created in 1848, 1872, 1924 and 1928. Because the Supreme Court of Virginia could review such a small percentage of circuit court decisions, in 1983 the General Assembly authorized a permanent intermediate appellate court called the Court of Appeals and it started hearing cases in 1985.

The General Assembly decided that Court of Appeals judges would serve eight-year terms, same as Circuit Court judges. Judges on the Supreme Court of Virginia serve 12-year terms.

In its first year, the new appeals court reduced the number of appeals filed at the Supreme Court of Virginia from 1,900 to 1,000. It's decisions in traffic and misdemeanor cases where no incarceration is imposed, in domestic relations matters, and in most cases processed initially by administrative agencies were final, unless the Supreme Court of Virginia chose to accept a case in order to create a definitive precedent for all lower court judges to follow.

Just 10 judges were authorized initially for the Court of Appeals, not the 12 initially proposed. The number of cases which could receive an automatic right of appeal from circuit court was limited. The General Assembly expanded the Court of Appeals to 11 judges in 1990. Trials were held in front of three-judge panels, though the full court could reconsider a case "en banc" with a panel of at least eight judges.

An additional six judges were authorized in 2021, after the court's jurisdiction was increased. The Genera Assembly permitted automatic appeals by defendants from any civil or criminal trial in circuit courts. Previously, only decisions by the State Corporation Commission and capital murder cases had been granted automatic rights to appeal. Virginia was the last of the 50 states to guarantee that decisions made at the initial trial court level (in Circuit Court) could be appealed.

The General Assembly also provided funding to add 19 more people to the office of the Attorney General to handle the increased workload, almost doubling the number of lawyers. In 2022, the Attorney General reported that the number of cases has increased from 250 per year to 300 in just January and asked for funding to hire 75 more lawyers.

While defendants were granted automatic hearings on appeal, the expanded court was left with the authority to quickly dismiss cases without merit or where case law was already clear. To help manage the workload, the law expanding the court also retained the right of the Court of Appeals to decline hearing an appeal requested by the prosecutors.

Adding six more judges was justified by the need to increase the court's capacity to accept more appeals. Expansion to a 17-judge court also allowed the Democratic leaders in the General Assembly to counterbalance years of judicial appointments by the Republicans, who had controlled the General Assembly and elected the judges for the previous two decades.

The expansion passed in the legislature's first Special Session in 2021, so electing judges required convening a second special session.

The Democrats controlled both houses in August, 2021. They filled eight rather than just six new positions on the Court of Appeals of Virginia, since one sitting judge announced his retirement and there was an unfilled vacancy. Increasing the diversity of the court was a priority. Prior to the new selections, the 11-member Court of Appeals of Virginia had only one black judge and three female judges. Only one came from Northern Virginia, where Republican influence was weak. The Republicans who controlled the General Assembly between 2000-2020 elected judges from areas which voted for Republicans.

Of the eight new judges, four were African-American and four identified as female. Only three of the new judges were white males. Three of the new appointees came from Northern Virginia, and none came from Southside or Southwest Virginia beyond Roanoke. The Democrats who controlled the General Assembly in 2021 elected judges from areas which voted for Democrats. However, neither party chose to elect judges to the Court of Appeals from Southside or Southwest Virginia.

Perhaps even more significantly, in 2021 people with a background as public defenders and in legal aid were elected. Traditionally, appointees had been former prosecutors or from the Attorney General's office and not defense attorneys; roughly 90% of criminal convictions were affirmed on appeal. Only two of the eight chosen in 2021 were serving as a Circuit Court judge, reflecting the Democratic dissatisfaction with judges chosen when Republicans controlled the General Assembly.

Those two selections created vacancies for the General Assembly, which recessed briefly rather than adjourned from the special session. "Recessing" blocked Governor Northam from making appointments to the two newly-vacant Circuit Court positions. The legislature finished its session by selecting judges to fill the Circuit Court, District Court, and Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court vacancies across Virginia.

Republican members of the legislature complained that Democrats interviewed candidates in secret, and released the biographical data of their selections less than a day before the vote. The Republicans also complained that the Democrats were "packing the court" with eight new judges that reflected the party's philosophy, but the Republicans followed the traditional pattern and expressed their opposition by not voting on the appointments rather than casting "no" votes.

The Democratic chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee stated that it was time for rebalancing:16

- Well, they picked the courts the last 20 years.

All judges in Virginia state courts are elected by the General Assembly. Members serving on the Courts of Justice committee in the House of Delegates, and on the Judiciary Committee in the State Senate, have the greatest influence in choosing who becomes a judge, but both the House of Delegates and the State Senate jointly need to approve every judge. The governor has no official authority to nominate a candidate, and can not veto a decision. However, governors can make interim appointments to fill vacancies until the General Assembly meets again.

If legislators are not satisfied with a judge's performance or object to a judge's decisions, they can not "fire" the judge during the fixed term of appointment. The only option is impeachment. If legislators are impressed favorably by a judge, they can elect them to serve in a higher court. Such promotions creates a vacancy that will be filled by another judicial appointment. Choosing a serving General District Court to start an eight-term term as a Circuit Court judge creates an opportunity for legislators to reward an ally and appoint a new General District Court judge to serve a six-year term.

Judges can be re-elected at the end of their term, but the legislators have the option to choose a different person for the next eight-year term. In 2021 the General Assembly chose not to re-elect a judge who had served for two terms on the General District Court in Chesterfield County. The House of Delegates included her name on their list of recommended judges, but two State Senators from her area objected to the re-appointment. Legislators re-elected her in 2015 despite local objections that she imposed greater penalties against people of color, perhaps because she had previously been a prosecutor. Objections to her decisions continued during her second term. In 2021 her name was stripped from the list passed out of the Senate Judiciary Committee for consideration by all 40 members.17

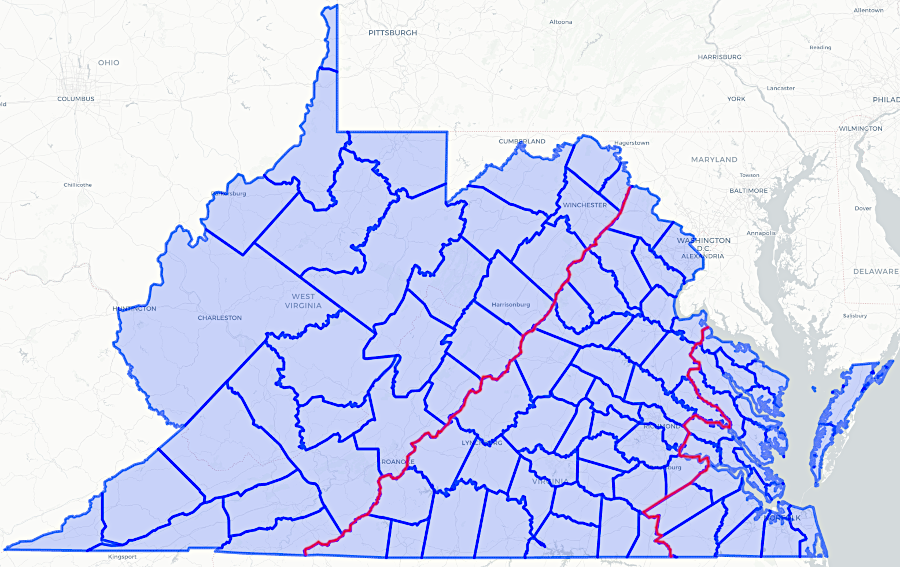

18 District Courts were established in 1789

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

When a judge completes a term (or retires/dies), the two houses of the General Assembly must elect a replacement. The new judge chosen by the legislature will serve a full 8-year term on District/Circuit Court, or a 12-year term on the Virginia Supreme Court. If the General Assembly is not in session when a vacancy occurs, or if it adjourns without choosing a new judge, the governor can appoint one. As defined in the 1971 constitution, gubernatorial appointees serve only until 30 days after the start of the next session of the General Assembly.

In 2015, a member of the Supreme Court of Virginia retired when the General Assembly was not in session. Governor McAuliffe appointed a replacement. Governor McAuliffe was a Democrat, and at the time Republicans controlled both houses of the General Assembly.

The governor's appointee had the support of the Republican chair of the House Courts of Justice Committee, but the majority of the Republican caucus quickly made clear that another person would be elected when the legislature met again. The Republicans replaced the governor's appointee when the General Assembly reconvened for its general session at the start of 2016.

Political control of the General Assembly was split in 2022, with Republicans controlling the House of Delegates and Democrats controlling the State Senate, when retirements from the Virginia Supreme Court created two vacancies. The two houses struggled to agree on two replacements. If the General Assembly adjourned without appointing two people to serve 12-year terms, then Republican governor Glenn Youngkin could appoint two judges who would serve until the legislature met again. That affected the negotiations, which one scholar suggested could have been a standard split-the-difference compromise:18

- It should not be that hard. Democrats get one and Republicans get one and hopefully everybody can vote to elect them and go home.

Links

the Judicial Center and jail in the center of Manassas is located on land still within Prince William County

Source: Manassas Courthouse - #341

References

1. Armisted R. Long, "The Constitution of Virginia: An Annotated Edition," J. B. Bell Company, 1901, p.112, https://books.google.com/books?id=djcUAAAAYAAJ (last checked December 17, 2014)

2. "The Constitution of Virginia: June 29, 1776," The Avalon Project, https://www.law.gmu.edu/assets/files/academics/founders/VA-Constitution.pdf (last checked February 14, 2021)

3. "A Guide to the Court of Admiralty Records of the Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts, 1775-1788," Library of Virginia, https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=lva/vi04856.xml; "Jurisdiction: Admiralty and Maritime," Federal Judicial Center, https://www.fjc.gov/history/courts/jurisdiction-admiralty-and-maritime; "Admiralty," Legal Information Institute, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/admiralty (last checked February 12, 2021)

4. "Jurisdiction Information," Library of Virginia, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/burned_juris/Jurisdiction_info.htm; "District Court Information," Library of Virginia, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/burned_juris/District_%20Court_info.htm; "Superior Courts of Chancery Information," Library of Virginia, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/burned_juris/Superior_Courts_info.htm; "Court Records History, City of Fredericksburg, https://www.fredericksburgva.gov/1000/Court-Records-History; Richard C. Poage, "History of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia," Honors Thesis, Paper 653, 1935, pp.2-3, p.7, p.10, https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1662&context=honors-theses; "A Short History of the Supreme Court of Virginia," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/scv/supreme-court-of-virginia/; Robert Weathers, "Wythe 102," Colonial Williamsburg, March 17, 2020, https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/learn/living-history/wythe-102/; "Jamestown to Richmond: Judicial Authority in Virginia since 1619," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/virginia-judicial-history/; "A Collection of All Such Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia: of a Public and Permanent Nature as are now in Force, with a Table of the Principal Matters to Which are Prefixed the Declaration of Rights, and Constitution, or Form of Government," Wythepedia, William and Mary Law Library, http://lawlibrary.wm.edu/wythepedia/index.php/Collection_of_All_Such_Acts_of_the_General_Assembly_of_Virginia_(1794)#cite_note-8 (last checked February 14, 2021)

5. Richard C. Poage, "History of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia," Honors Thesis, Paper 653, 1935, p.7, pp.18-19, https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1662&context=honors-theses; "A Short History of the Court of Appeals of Virginia," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/scv/supreme-court-of-virginia/; "Commonwealth v. Caton," Wythepedia blog, William and Mary Law Library, http://lawlibrary.wm.edu/wythepedia/index.php/Commonwealth_v._Caton; "Commonwealth V. Caton 4 Call's (Va.) Reports (1782)," Encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/politics/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/commonwealth-v-caton-4-calls-va-reports-1782 (last checked March 10, 2021)

6. "Article VI - Judiciary Department," Constitution of Virginia, 1851, http://www.wvculture.org/history/government/1851constitution01.html; "Jurisdiction Information," Library of Virginia, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/burned_juris/Jurisdiction_info.htm (last checked February 14, 2021)

7. "A Short History of the Supreme Court of Virginia," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/scv/supreme-court-of-virginia/; "Article VI Judiciary Department," Constitution of Virginia, 1864, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.35112105038196 (last checked February 14, 2021)

8. "A Short History of the Supreme Court of Virginia," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/scv/supreme-court-of-virginia/; "Article VI - Judiciary Department," Constitution of Virginia, 1870, http://vagovernmentmatters.org/files/download/424/fullsize; "Jamestown to Richmond: Judicial Authority in Virginia since 1619," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/virginia-judicial-history/ (last checked February 14, 2021)

9. "A Short History of the Supreme Court of Virginia," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/scv/supreme-court-of-virginia/ (last checked February 14, 2021)

10. "Magistrate Services," Virginia's Judicial System, http://www.vacourts.gov/courtadmin/aoc/mag/about.html; "Magistrate," City of Roanoke, https://www.roanokeva.gov/882/Magistrate; "RD347 - Report on the Virginia Magistrate System," Supreme Court of Virginia, 2007, https://rga.lis.virginia.gov/Published/2007/RD347; "H 903 - An Act to amend and reenact §§ 3.1-383, 3.1-796.93:1, 3.1-796.116, 3.1-796.126:10, 8.01-126, 8.01-537, 8.01-540, 15.2-1704, 15.2-1710, 16.1-135, 19.2-5, 19.2-34 through 19.2-39, 19.2-43, 19.2-44, 19.2-45, 19.2-46, 19.2-46.1, 19.2-48, 19.2-48.1, 19.2-77, 19.2-81.3, 19.2-119, 19.2-152.4:3, 20-70, 20-84, 27-32, 27-32.1, 27-32.2, 27-37.1, 37.2-808, 37.2-809, 37.2-1103, 37.2-1104, 43-29, 46.2-104, 49-6, 55-205, 55-230, 59.1-98, and 59.1-106 of the Code of Virginia and to repeal §§ 19.2-30 and 19.2-41 of the Code of Virginia, relating to magistrates," Virginia General Assembly, March 11, 2008, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?081+ful+CHAP0551&081+ful+CHAP0551 (last checked March 6, 2021)

11. "Jamestown to Richmond: Judicial Authority in Virginia since 1619," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/virginia-judicial-history/; "General District Court," Virginia's Judicial System, Supreme Court of Virginia, http://www.courts.state.va.us/courts/gd/home.html; "Judicial Selection Overview," Virginia Division of Legislative Services, http://dls.virginia.gov/judicial.html (last checked February 14, 2021)

12. "General District Courts," Virginia's Judicial System, http://www.courts.state.va.us/courts/gd/gdinfo.pdf (last checked March 5, 2021)

13. "The Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court," Virginia's Judicial System, http://www.courts.state.va.us/courts/jdr/jdrinfo.pdf (last checked March 5, 2021)

14. "The Circuit Court," Virginia's Judicial System, http://www.courts.state.va.us/courts/circuit/circuitinfo.pdf (last checked March 5, 2021)

15. "The Circuit Court," Virginia's Judicial System, http://www.courts.state.va.us/courts/circuit/circuitinfo.pdf; "Indict a ham sandwich," The Big Apple blog, July 15, 2004, https://www.barrypopik.com/index.php/new_york_city/entry/indict_a_ham_sandwich/ (last checked March 5, 2021)

16. "A Short History of the Court of Appeals of Virginia," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/a-short-history-of-the-court-of-appeals-of-virginia//; "Opinion: Virginia should expand its appeals court, and by extension — justice," Washington Post, January 15, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/virginia-should-expand-its-appeals-court-and-by-extension--justice/2021/01/15/3912d4fc-569f-11eb-a817-e5e7f8a406d6_story.html; "About the Court of Appeals of Virginia," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/about-the-court-of-appeals/; "Jamestown to Richmond: Judicial Authority in Virginia since 1619," Supreme Court of Virginia, https://scvahistory.org/virginia-judicial-history/; "SB 1261 Court of Appeals; expands jurisdiction, increases from 11 to 17 number of judges on Court.," Virginia General Assembly, 2021 Special Session I, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?211+sum+SB1261; "Judicial Selection Overview," Virginia Division of Legislative Services, http://dls.virginia.gov/judicial.html; "Virginia Court of Appeals set to get six new judges after lawmakers agree to expansion," Virginia Mercury, March 8, 2021, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2021/03/08/virginia-court-of-appeals-set-to-get-six-new-judges-after-lawmakers-agree-to-expansion/; "Virginia Democrats reshape Court of Appeals with eight new appointments," Virginia Mercury, August 10, 2021, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2021/08/10/virginia-democrats-reshape-court-of-appeals-with-eight-new-appointments/; "Lawmakers recess special session after electing eight judges to Court of Appeals and some to lower courts," Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 11, 2021, https://richmond.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/lawmakers-recess-special-session-after-electing-eight-judges-to-court-of-appeals-and-some-to/article_a4ac22f6-69af-5cd0-a6aa-01d42479f140.html; Dick Hall-Sizemore, "Oyez, Oyez. The Virginia Court of Appeals is Changing," Bacon's Rebellion, August 12, 2021, http://www.baconsrebellion.com/wp/oyez-oyez-the-virginia-court-of-appeals-is-changing/; "Schapiro: It's not exactly the 'People's Court' - yet," Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 11, 2021, https://richmond.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/schapiro-its-not-exactly-the-peoples-court-yet/article_4414fd9e-bf85-57c2-9fb6-e2019bbe12f8.html; "AG says staff can't keep up with flood of new criminal appeals," Virginia Mercury, February 21, 2022, https://www.virginiamercury.com/blog-va/ag-says-staff-cant-keep-up-with-flood-of-new-criminal-appeals/ (last checked February 21, 2022)

17. "State senate declines to reappoint Chesterfield judge," Chesterfield Observer, February 10, 2021, https://www.chesterfieldobserver.com/articles/state-senate-declines-to-reappoint-chesterfield-judge/ (last checked March 5, 2021)

18. "Constitution of Virginia," 1971, https://law.lis.virginia.gov/constitution.pdf?msclkid=f299af94cf9411ecad5beedf6915f203; "State Supreme Court vacancies remain unfilled during political standoff," Virginia Mercury, May 9, 2022, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2022/05/09/state-supreme-court-vacancies-in-play-in-political-standoff/; Carl Tobias, "Electing Justice Roush to the Supreme Court of Virginia," Washington and Lee Law Review, Volume 17, Issue 2 (2016), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr-online/vol72/iss2/8 (last checked May 9, 2022)

Virginia Government and Politics

Virginia Places