the Code of Virginia is readily available online, and legal publishers sell annotated versions to provide more context for lawyers

Source: Virginia Legislative Information System, Code of Virginia

the Code of Virginia is readily available online, and legal publishers sell annotated versions to provide more context for lawyers

Source: Virginia Legislative Information System, Code of Virginia

The "Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall" issued by Sir Thomas Gates in 1610 were published in London in 1612. Colonists in Virginia learned about them by voice. There was no means of printing the laws at the time in Jamestown, so ministers were commanded to announce them in church:1

In 1618 the Virginia Company sent instructions for the new governor which it appointed for Virginia. The instructions to Sir George Yeardley are know as the "Great Charter." When the king began appointing governors after Virginia became a royal colony in 1624, royal officials sent instructions to the royal governors. The instructions were interpreted by the governor, and he was not required to publicize to the colony or even share them with the Governor's Council.

Instructions were not laws which could be interpreted by county judges or colonial officials in ways that differed from the governor's decisions. Governors had the freedom to follow, postpone, modify, or ignore the instructions they received, though at the risk of being recalled back to England.

The Grand Assembly began passing laws in 1619. The burgesses in the Grand Assembly had the same options as the governor when passing legislation, though resistance to royal instructions created a risk. The governor could issue an order to prorogue the legislature and call for new elections of burgesses.

In the 1620's, the governor began to appoint commissioners to make routine legal decisions at locations distant from Jamestown. In 1634, counties with "county courts" were established. Two years before the formal creation of counties, the General Assembly ordered that all the laws passed to date be read to everyone at the start of the monthly courts:2

The March, 1632 Grand Assembly passed legislation which was inconsistent with previous laws. To reduce confusion, the Grand Assembly met again on September 4, 1632 and made its first systemic revisal of existing laws. All existing acts were repealed, and then 61 laws were passed. Many simply renewed laws which had just been repealed, but the process created clarity regarding which laws were in force. Of the 61 laws, 17 dealt with governing the Anglican church.

The "revisal" process of repealing all laws then in force and passing a new collection was repeated in 1643. The requirement to read all the laws at the meetings of the local courts was eliminated. Also in 1643, the "monthly courts" were renamed "county courts" and were required to meet only six times each year.

While Governor William Berkeley was displaced from office during the English Civil War and the colony was governed by Protectorate Governors, laws were compiled again. The committee which assembled the list identified 131 laws in force in 1657, excluding those related to church governance. The vestries were given much greater authority to manage their own business, reducing the workload at the General Assembly.

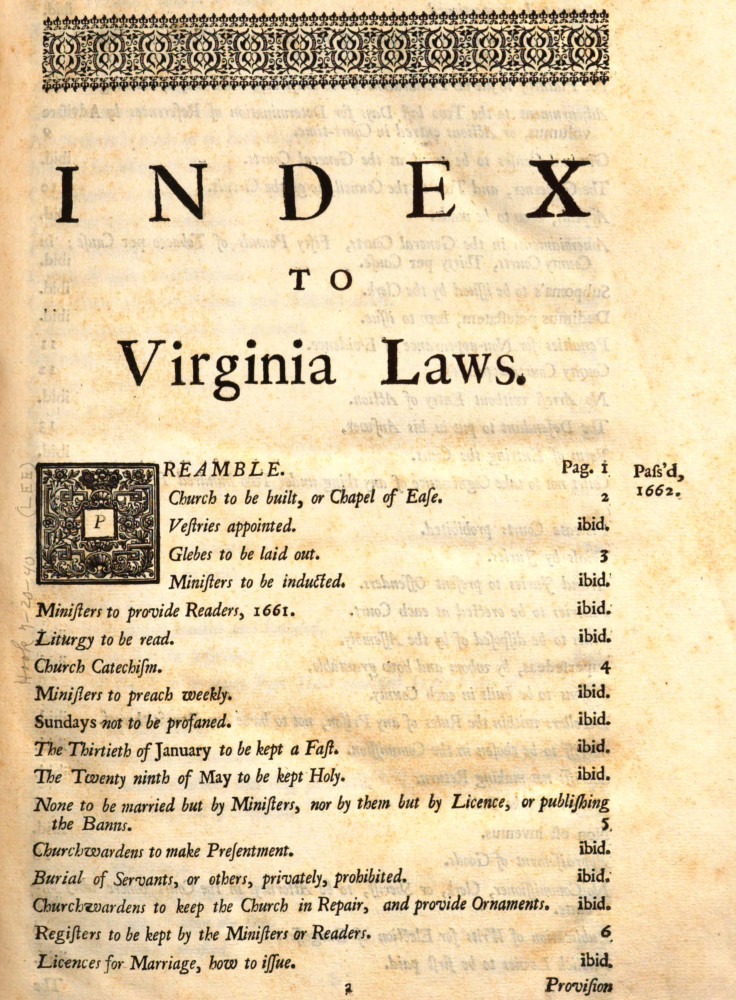

After the restoration of King Charles II, the General Assembly again revised the laws. Vestries lost the autonomy granted in 1658, and the legislature passed "An act for the suppressing the Quakers." Francis Morrison and Henry Randolph did the 1661-62 compilation, and Randolph was granted a 10-year license for exclusive publication. A manuscript copy was sent to London, since Governor Berkeley was visiting there, but importation of any printed version from England was prohibited.

The 1661-62 compilation was a useful document in Jamestown, providing a reliable reference. There was no printing press in Virginia, and the 1661-62 compilation was never printed in the colony. The county courts relied upon manuscript copies of individual laws sent from Jamestown to each county, even as the General Assembly arranged for "publication" of a collection of all the laws in force at a particular time. If someone suspected an error in transcription, they could check the originals retained in Jamestown - but in the 1600's, all documents produced in Virginia were in manuscript form.

The county court commissioners, also known as justices of the peace, relied upon the common law to make decisions. Their perspective of justice and fairness was enhanced by their personal knowledge of laws passed by the General Assembly, but the knowledge of those laws varied widely across the colony. Precedents were poorly documented. Legal decisions by the General Court (later known as the Quarter Court) and other county courts were not compiled, printed, or shared in an organized way. Since the members of the General Court typically served for life, they had some institutional memory and could create some consistency in the application of the laws when hearing appeals of decisions made by county courts.

Burgesses, lawyers, and judges created individual law libraries with manuscript copies of laws and decisions for their personal use. They may have made notes in the margins, or added slips of paper to document arguments made in court, decisions on cases, and discussions with other lawyers. However, those documents were kept in private libraries, and were not circulated for use by all lawyers.

In the mid-1680's, the "Purvis Edition" was published in London. It claimed to be "A complete collection of all the laws of Virginia now in force, Carefully Copied from the Assembly record," but omitted many of the laws in effect at that time. No copy of that printed publication appears to have reached Virginia.

In 1699, the General Assembly tasked another committee with three men from the Governor's Council and six from the House of Burgesses to compile the laws again. The committee completed the task in 1705. The General Assembly adopted it, repealing all previous laws again and establishing a new baseline.

The 1705 product remained in manuscript form, but two publications were produced in London. A partial list of laws in force in 1720 was published in 1722. In 1727, the John Baskett in London printed the Baskett Edition, which claimed to include the laws passed by the General Assembly between 1662-1715.3

The first compilation of Virginia laws to be printed in the colony was A Collection of All the Acts of Assembly, Now in Force, in the Colony of Virginia with the Titles of Such as are Expir'd, or Repeal'd. It was published in 1733, and included all the laws passed by the General Assembly between 1661-1732. That publication was endorsed by the legislature, but apparently the initiative to print a new baseline of the laws in effect in 1732 was undertaken by private investors without government funding.

a compilation of Virginia laws was published in London in 1727 and used there, while the General Assembly published a collection in 1733 that was used in Virginia

Source: HathiTrust, Acts of Assembly, passed in the colony of Virginia, from 1662, to 1715. Volume I

Another nine-person committee was appointed in 1745. Its work, completed in 1748, was printed in Williamsburg in 1752 as The Acts of Assembly, Now in Force, in the Colony of Virginia. Another update with the same name was published by Williamsburg printer William Rind in 1769, thanks in part to financial support from Thomas Jefferson. It totaled 500 pages.4

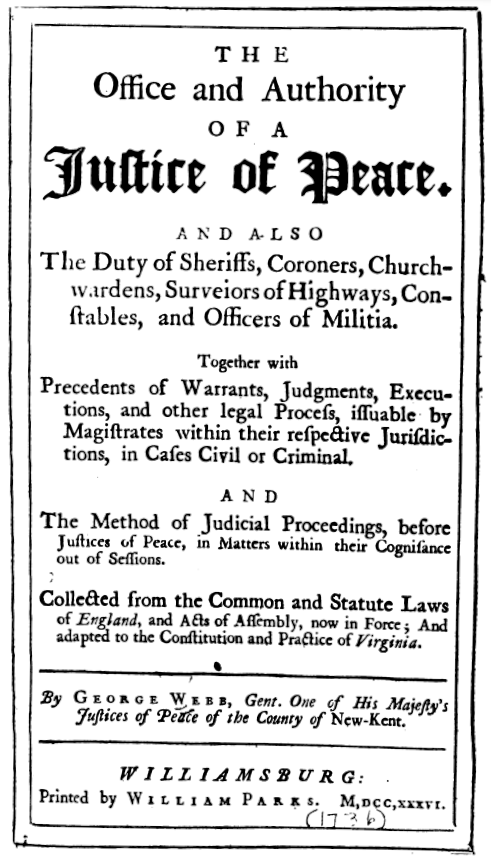

Only two books were printed for use by Virginia lawyers during the colonial era. George Webb published The Office and Authority of a Justice of Peace in 1736, three years after A Collection of All the Acts of Assembly, Now in Force, in the Colony of Virginia with the Titles of Such as are Expir'd, or Repeal'd was printed. At the same time, Edward Barradall began to compile decisions by the General Court, becoming the colony's first law reporter.5

the first book intended for use by lawyers and justices of the peace in Virginia's county courts was published in 1736

Source: George Webb, The Office and Authority of a Justice of Peace

In 1774, The Office and Authority of a Justice of Peace Explained and Digested was published. It was written primarily by Richard Starke, though he died before publication and someone else finished the manuscript.6

the first book intended for use by lawyers and justices of the peace in Virginia's county courts was published in 1736

Source: William and Mary Law Library, A Collection of All Such Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia: of a Public and Permanent Nature as are now in Force...

In 1776, the General Assembly created a Committee of Revisors composed of Thomas Jefferson, Edmund Pendleton, George Wythe, George Mason, and Thomas Ludwell Lee. The five men met in Fredericksburg in January, 177, and divided up the work. Then Thomas Ludwell Lee died and George Mason declined to participate further, so three men did the work of updating colonial-era legislation in anticipation that the American Revolution would successfully eliminate the role of officials appointed by King George III and any powers that might be asserted by Parliament.

Each of the three "revisors" took the lead for a portion of the law, as described by Jefferson:7

The Committee of Revisors submitted a report in 1779 indicating 126 laws needed to be changed. It was not a compilation of all legislation that was in effect in 1776; it did not include expired, repealed or obsolete laws. The package of proposals was bold, and passage in 1779 would have fundamentally reformed the pre-Revolution legislation. However, it took until 1784 before the Report of the Committee of Revisors Appointed by the General Assembly of Virginia in MDCCLXXVI was printed, and the General Assembly consideration of it occurred in 1785-86.

Jefferson did not wait for the Committee of Revisors to collect the laws and agree upon what changes were needed before he proposed his own revisions to the General Assembly. He actively sought to revise old laws to incorporate the principles articulated in the Bill of Rights, and to replace aristocratic with republican principles. In particular, he targeted laws that controlled inheritance such as entail and primogeniture.

Whenever he identified a political opportunity, he proposed legislation in 1776-1779 that advanced his agenda. Those piecemeal revisions occurred in a piecemeal fashion rather than a one-step process following a report by the Committee of Revisors. Jefferson's efforts led to revision of of over 60 laws. His priority was revision of the laws, rather than compiling them or organizing them by subject into a "code."8

George Wythe ended up completing a compilation of all laws passed after 1768 and still in effect.

Wythe was one of three people appointed to Virginia's High Court of Chancery in 1776, and ended up as the only judge. In 1783, after it was clear that Britain would accept the independence of 13 of its former American colonies, the General Assembly ordered a collection of the laws in effect. In 1784 Wythe arranged for publication of A Collection of All Such Public Acts of the General Assembly, and Ordinances of the Conventions of Virginia, Passed since the Year 1768, as are Now in Force with a Table of the Principal Matters; Published under Inspection of the Judges of the High Court of Chancery, by a Resolution of General Assembly, the 16th day of June 1783.

Wythe compiled what became known as the Chancellors' Revisal, but that publication did not organize the laws by topic into a formal code.9

the High Court of Chancery managed the compilation of laws published in 1784

Source: William and Mary Law Library, A Collection of All Such Public Acts of the General Assembly, and Ordinances of the Conventions of Virginia...

The Chancellors' Revisal was a resource for James Madison, when he returned to the General Assembly in 1785. By then, there was no longer a need for action on eight of the bills that the Committee of Revisors 1779 had proposed to change. The laws had already been altered, expired, or been overcome by events.

Madison was the champion in 1785 for completing the legal reformation proposed by the revisors. He introduced a bill to modify the remaining 118 laws, since eight of the 126 identified in 1779 fhad already been "overcome by events." Thomas Jefferson was in France representing the United States as its ambassador, so in 1785 Madison led the initiative to reform the laws as proposed six years earlier by the Committee of Revisors.

The General Assembly acted first on 35 of the bills introduced by Madison. A major accomplishment that year was adoption of the Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom. In the October 1786 session, 23 more laws were revised. Changes in three more were approved in 1789.10

The General Assembly ordered an update in 1790, and a six-person committee provided its report in 1792. A Collection of All Such Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia: of a Public and Permanent Nature as are now in Force, with a Table of the Principal Matters to Which are Prefixed the Declaration of Rights, and Constitution, or Form of Government was published at state expense in 1794. The only law included from prior to 1776 was "An Act for confirming and better Securing the Titles to Lands in the Northern Neck, held under the Right Honorable Thomas Lord Fairfax." Annual supplements were issued until a new compilation was published in 1803.11

the 1794 compilation included brief descriptions in the margins of the legal topic, but did not cross-reference laws or cite decisions by judges and juries

Source: William and Mary Law Library, A Collection of All Such Public Acts of the General Assembly, and Ordinances of the Conventions of Virginia...

The "Code of 1803" republished the 1794 list of laws, and appended to it those which had been passed since 1794. The General Assembly passed legislation to authorize the 1803 publication, but chose not to fund the printing. The update was completed and sold by Samuel Pleasants Jr. and Henry Pace. Pleasants issued updates in 1808 and 1812.12

With authorization by the General Assembly but without funding, William Waller Hening succeeded in publishing 13 volumes between 1808-1823 which documented most (but not all) laws passed between 1619-1792. Like Thomas Jefferson, Hening collected manuscript copies of laws from court clerks, justices of the peace, and officials in Williamsburg and Richmond. He relied upon them to identify errors and omissions in the printed versions, so his publications were more accurate.

The General Assembly finally supported publication of legislation organized by subject matter, rather than just chronologically, to form the first Code of Virginia. The legislature provided an eight-page list of laws, and directed Benjamin Watkins Leigh to:13

Leigh published The Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia: Being A Collection of all such Acts of the General Assembly, of a Public and Permanent Nature as are now in Force in 1819. William Munford and William Waller Hening, who was still compiling laws in chronological order, helped Leigh to organize the laws in 23 segments with 262 chapters. For the first time, lawyers and judges could use the 1819 code to identify laws relevant to the issues in a case, independently from whenever those laws had been passed. The adoption of the 1819 Code by the legislature reduced the burden on a lawyer to determine the relevant legislation on which to base a legal argument.

In 1833, a supplement was published to update the 1819 Code of Virginia.

the first official Code of Virginia was published in 1819

Source: HathiTrust, The Revised code of the laws of Virginia (1819)

General revisions of the Code of Virginia were made in 1849, 1887, 1919, and 1950.

The 1849 Code was produced by Conway Robinson and John M. Patton. Through careful editing, they compacted their summary of all Virginia civil and criminal laws in less than 1,000 printed pages, and carefully reviewed he proposals with key members in the General Assembly. The laws were organized into 56 titles with 216 chapters, with individually numbered sections in each chapter. As one scholar has noted:14

The General Assembly officially adopted the Code of 1849, giving it the force of law. George W. Munford updated it in 1860 and 1873, but the General Assembly did not officially adopt those versions. The 1860 update was necessary after the state constitution was changed in 1851.

The General Assembly ordered another official update in 1884. Waller R. Staples, John W. Riely, and Edward C. Burks, three former members of the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals, performed the task.

The 1887 Code of Virginia established a now-standard numbering system for the 4,205 sections, creating a consecutive sequence that made citation far easier. Conscientious lawyers would purchase the code and add to it the laws passed in later sessions, so they had a complete compilation which was partially by topic and partially chronological.

the 1887 Code of Virginia established the standard numbering system still used for citing laws

Source: HathiTtust, The Code of Virginia (1887)

In his own initiative, in 1894 John Garland Pollard provided a way to connect new laws to the Code of 1887 sections. As new laws were passed by the General Assembly, he published Amendments to the Code of Virginia. They were intended to be pasted over the old pages in the 1887 Code.

After participating in the convention that produced the 1902 state constitution, Pollard published a new Code of Virginia as Amended to Adjournment of General Assembly of 1904... Annotated. He recognized that the significant changes in the state constitution required a new publication, but his 1905 code was not adopted officially by the legislature.

The annotations added value beyond the simple text of the laws by describing how relevant decisions were made by judges and juries, and by summarizing legal interpretations of the laws. For the next 20 years, he published Pollard's Code Biennial after each meeting of the General Assembly. The updates were valued in large part for the annotations, listing relevant cases and summarizing the rulings of judges so lawyers understood precedents better.

John Garland Pollard's success with his annotated codes helped him get elected as Attorney General in 1913, and as Governor in 1929.

The next official update to the code was ordered by the governor in 1914, approved by the General Assembly in 1918, and went into effect in 1919. The 1919 Code of Virginia required 63 titles and 6,571 consecutively numbered sections. The Michie Company established its dominance of the legal publishing business in Virginia when it issued The Code of Virginia as Amended to Adjournment of General Assembly 1924. It included information on how laws had been modified, tracing statutes back in time to 1887.

Michie issued a new version every six years, plus biannual supplements after General Assembly meetings until the next edition. (Regular annual meetings of the legislature began only in 1970.) The company struggled to categorize legislation passed in the 1920's and 1930's, especially laws passed in response to the Great Depression, using the structure and subject headings created in 1919.

In 1946, the General Assembly created a Commission on Code Recodification. Two years later, the legislature approved a new code to go into effect in 1950, and Michie required 10 volumes to publish the Code of Virginia 1950. The commission was made permanent, as the Virginia Code Commission. That led to the current process of revising the code title by title. Lawyers and judges still use the Code of Virginia 1950 today, since it has been updated regularly but never replaced.15

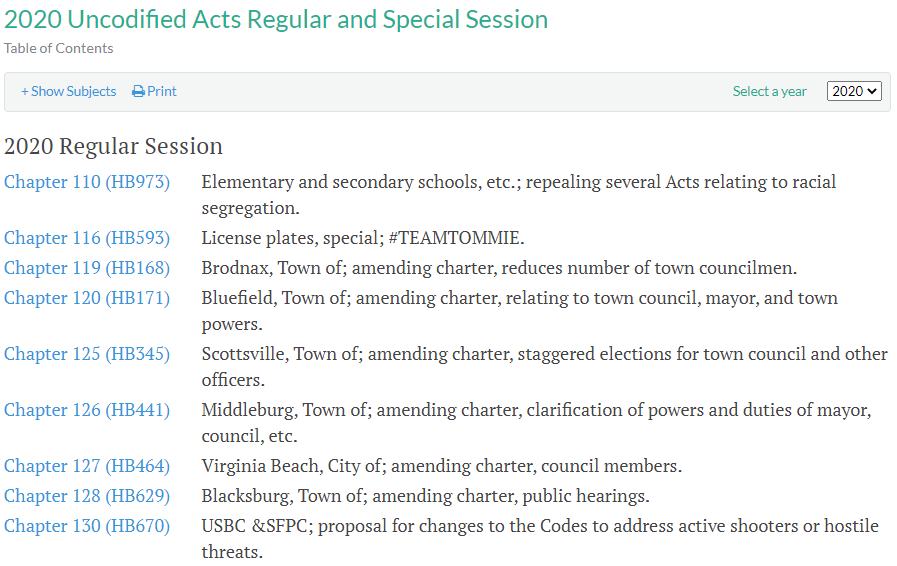

Today there are 76 titles in the Code of Virginia. New Acts of the Assembly intended to be permanent are codified. The Code of Virginia is not modified to include laws intended to be limited in duration, such as the two-year state budget. Bills with only local or regional application, such as modifications to town charters, are also left out of the Code of Virginia. Uncodified Acts of the Assembly are known as Section 1 bills. They are available in the annual Acts of Assembly publication, listed by chapter numbers according to the date each bill (codified or not) becomes law.

laws of short duration or limited local impact are published as Chapters of the Acts of the Assembly, but not included in the annual update to the Code of Virginia

Source: Virginia Legislative Information System, Uncodified Acts

The Virginia Code Commission is empowered to renumber, rename, and rearrange Code of Virginia titles, chapters, articles, and sections, to correct printing errors. The updated code is published annually on July 1, since laws passed by the General Assembly go into effect then unless there is a special enactment clause. Private publishers continue to produce their own versions, adding annotations and editors' notes. The public website, the Virginia Law Portal, omits that copyrighted information, but the bottom of each section includes data on when that section was implemented or amended.

As described by the Virginia Code Commission:16

The Code of Virginia is not the only resource required by lawyers to understand court procedure, how to interpret legislation, or how to understand decisions by judges that established precedents.

William Waller Hening published The New Virginia Justice in 1795. It served as the primary guide for procedures in the courtroom, used by justices of the peace and lawyers for three decades.17

In 1815, William Brockenbrough added to the available literature which could be used by judges and lawyers, in addition to the compilations of the laws. He published a book describing cases which had been decided by the General Court. A Collection of Cases Decided by the General Court of Virginia was followed in 1826 by a second volume, Virginia Cases, or Decisions of the General Court of Virginia, in 1826.18

The Virginia State Bar Association was founded in 1888. At the time, any man of "honest demeanor" could be licensed as an attorney by two judges, and the assessment of a person's qualifications by those judges could be superficial. At the first meeting of the new association, it was noted that:19

The General Assembly responded to pressure from the bar association in 1896, and required the justices on the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals to interview and license new lawyers. The Virginia Board of Bar Examiners took on that responsibility in 1910.

In 1876, Robert Peel Brooks became the first black man licensed to practice. By 1890, 38 of the 1,649 attorneys were non-white, but 100% were male until 1920.20

the second book intended for use by lawyers and justices of the peace in Virginia's county courts was published in 1774

Source: Fine Antiquarian Books, The Office and Authority of a Justice of Peace (written by Richard Starke)