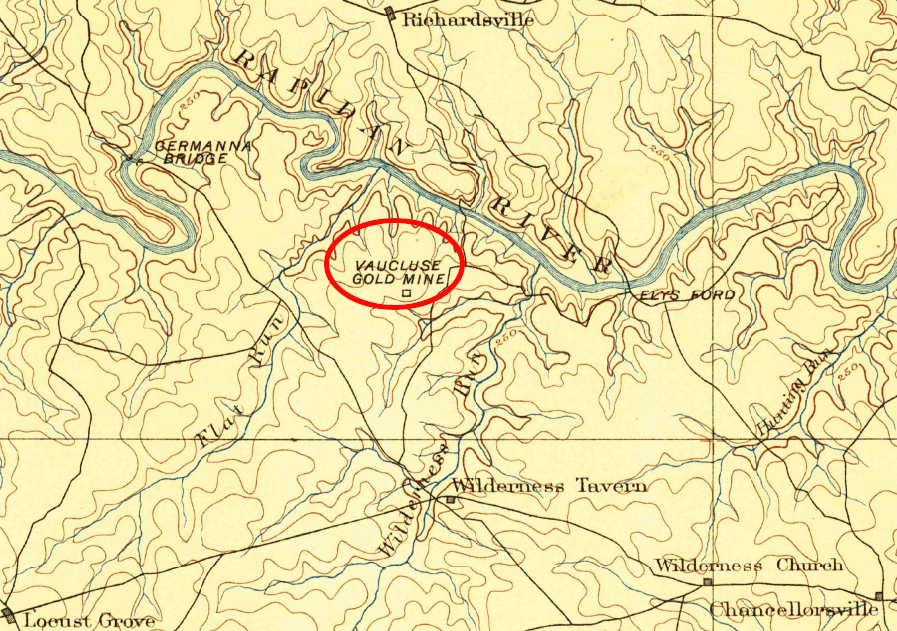

the Vaucluse Mine is located along Shotgun Hill Branch, a tributary of Wilderness Run

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Spotsylvania VA 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1887)

the Vaucluse Mine is located along Shotgun Hill Branch, a tributary of Wilderness Run

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Spotsylvania VA 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1887)

The Vaucluse Mine was opened after gold was discovered in 1831; production by the Virginia Mining Company began in 1832. Dr. Peyton Grymes owned and operated the mine using enslaved labor. His father, Benjamin Grymes, had purchased the land from the grandson of Gov. Alexander Spotswood.1

Initially just the placer deposits in the stream gravels were mined. The ore zone was exposed on the surface and was as much as 40 feet wide. The lode deposit was discovered only after several years of mining at the surface:2

Dr. Peyton Grymes sold the 200-acre site to an English firm, the Liberty Mining Company, in 1844. That firm invested the capital required to open shafts and process the ore, enabling production of gold from the lode deposit in addition to the placer deposit on the surface.

The 1844 sale price was $11,000, which was equivalent to about $400,000 in 2022. Dr. Grymes's two unmarried sisters, Hannah and Lucy, retained 100 adjacent acres where they lived in their mansion house called Vaucluse.3

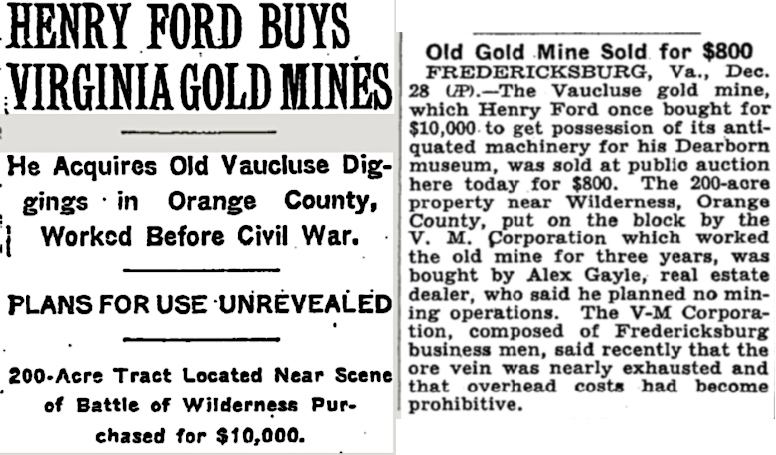

Developing the deposit at Vaucluse included excavating two cuts in the placer deposits 60 feet deep, 75 feet wide, and 120 feet long to extract the gold.

open cuts were used initially to remove ore at the surface, before shafts were dug at the Vaucluse Mine

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Gold deposits of the southern Piedmont (Plate 19 B)

Shafts were excavated in the 1850's, and materials thought to include gold was crushed by two techniques powered by a 120-horsepower steam engine. In the first step, water pushed the material across a screen with holes, so smaller ("fine") material dropped through the screen and was separated from larger rocks. At Vaucluse mine, the water came from Shotgun Hill Branch, a tributary of Wilderness Run.

The fine material was crushed in six Chilean mills. In each Chilean mill, a heavy cast-iron wheel turned in a cast-iron trough to pulverize the rock and free up the fine gold particles attached to quartz or other unwanted "gangue" material. The slurry of pulverized rock was transported further by water into an amalgamator box with partitions that slowed the flow. When the pulverized material passed slowly over a bed of mercury ("quicksilver") in the box, the gold particles would combine chemically with the mercury to form a mixture (amalgam). The water carried the waste rock out of the box to form tailing piles.

At the stamp mill, gold-bearing rocks would be placed in cast-iron boxes. A heavy hammer would fall onto the rocks and steadily pulverize the ore. Small particles, including gold, could escape as water flowed through holes in metal plates at the bottom of a box. At Vaucluse before the Civil War, the gold in the pulverized material from the stamp mill was amalgamated in bowls rather than boxes:4

When water was turned off occasionally, the amalgam was collected from the bowls and boxes. It was then heated, driving off the mercury as a vapor and leaving valuable gold in the crucible. Miners sought to capture the mercury vapor and condense it for reuse, but mercury gradually accumulated at mining sites in the 1800's. Elevated levels of mercury are still present in the Orange County gold diggings.

Gold was discovered in California in 1848, vastly increasing the supply. Gold mining at Vaucluse, as well as operations at the nearby Melville, Grasty, Greenwood, Wilderness, Partrigde, Orange Grove, Culpeper, Love, and Embry mines, still continued until the Civil War. At the end of 1853, the mill was crushing fifty tons of ore daily. In one 80-day period, 556 ounces of gold were produced at Vaucluse Mine.5

After the Civil War, the Grymes family sold more parcels to Northern speculators interested in purchasing Orange County gold mines. Dr. Peyton Grymes's son, Peyton Grymes, Jr., sold two additional tracts separated by intervening gold-bearing lands on March 21, 1866. The buyers in Philadelphia later claimed that they were entitled to cancel the sale, because they mistakenly thought an abandoned shaft was included within the boundaries of the property they had purchased.

A lawsuit over the property sale ended up being resolved by a US Supreme Court decision. The buyers won at the Circuit Court level but lost at the US Supreme Court. Key to the final ruling was that the buyers had failed to object as soon as they discovered the shaft was not on the property, and because the buyers failed to establish that the abandoned shaft was the basis for purchasing the property. The fact that the shaft was already abandoned clearly indicated that its particular location was unproductive. Local miners were confident that valuable veins already exposed at the Greenwood and Melville mines passed through the property, including one vein with ore that was worth $500 to the ton, but a post-purchase investigation by the buyers did not excavate deep enough to expose the veins.

The US Supreme Court's final decision meant that the Grymes family was able to retain the money they had collected from the sale:6

Another attempt to open the mine failed in 1913. The Central Virginia Mining and Milling Company, a Rhode Island Company, was forced to relinquish control of the property. The land was finally sold in 1926 to a New York investor, John A. Standish. About 18 months of site preparation revealed a vein with ore worth $1B.OO per ton, but no gold was produced. Standish may have used the mine to sell worthless stock to uninformed/misinformed investors, and local workers were also left unpaid.

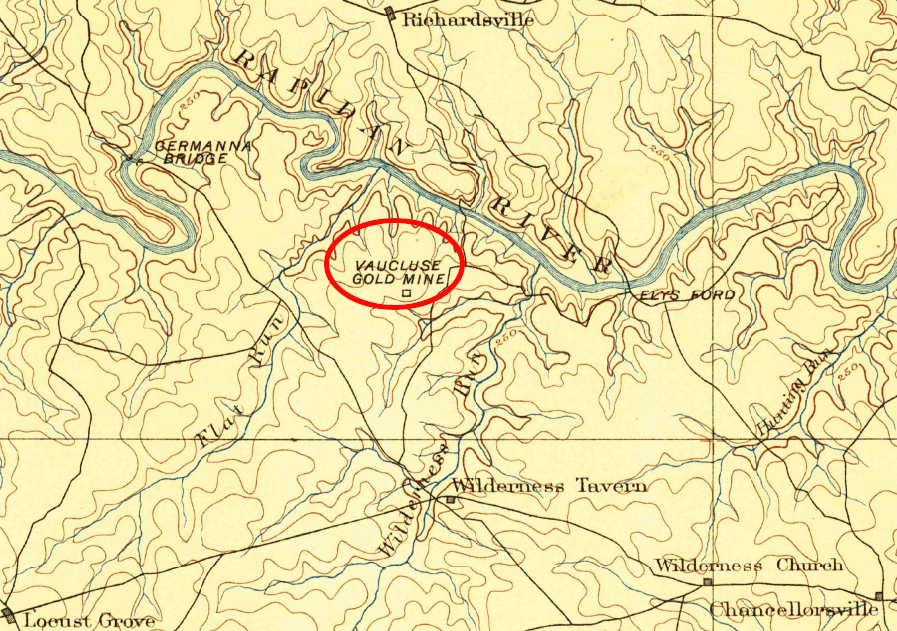

Through court order, the land was sold again in 1927. That buyer than sold the property to the Special Commissioner who had handled the last two sales, Judge A.T. Embrey from Fredericksburg. Embrey recognized that the timber was valuable, but in 1929 he sold the 200-acre tract that included the Vaucluse Mine to Henry Ford.7

Ford wanted the mining machinery, not the gold. A new road was cut through the woods so mill stones, a walking beam steam engine, several "stamps" for crushing ore, and three boilers could be removed. The boiler for the 100-horsepower engine was 30 feet long and 8 feet in diameter, and it was shipped along with most of the other equipment to Henry Ford's historical museum in Dearborn, Michigan, but in the end the two smaller boilers were left on the property. The steam engine was intended to part of an exhibit on the history of power.8

the Vaucluse Mine is located along Shotgun Hill Branch, a tributary of Wilderness Run

Source: New York Times, Henry Ford Buys Virginia Gold Mines (August 25, 1929) and Old Gold Mine Sells for $800 (December 29, 1938)

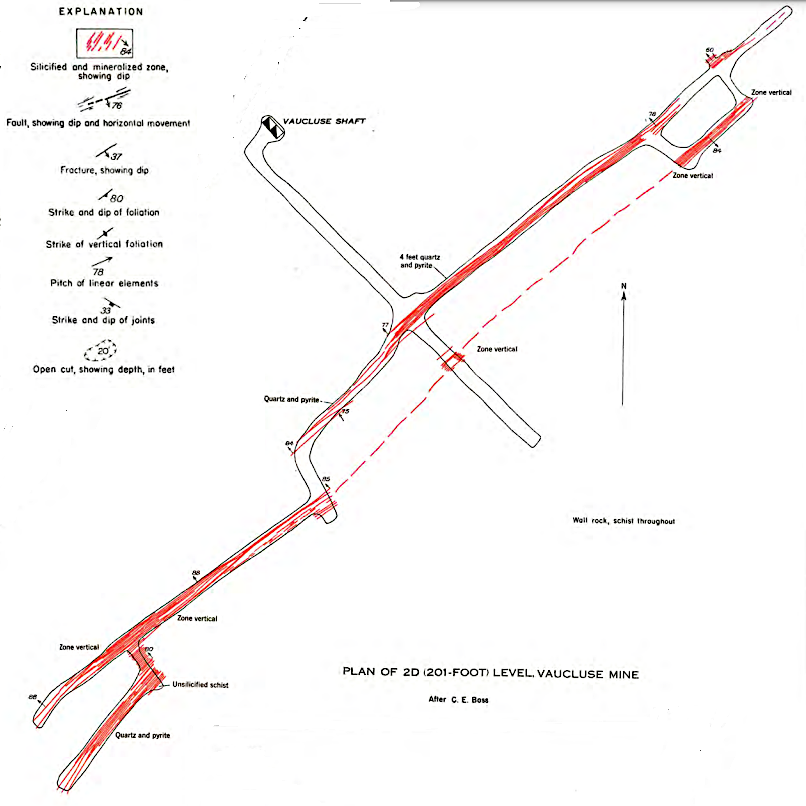

Ford sold the land in 1933 to the Rapidan Gold Corporation, which was reopening the Melville Mine north of the Vaucluse Mine, and mining restarted during the Great Depression. An old shaft west of the mineralized zone was cleaned out to its original depth of 80 feet. In cleaning out the shaft, the miners found an old "level" (horizontal shaft) driven into the ore body at 50 feet. Old tools and a pump were found at the bottom, indicating rapid abandonment - perhaps as the old miners had intersected an aquifer, and groundwater had flowed rapidly into the shaft.

The shaft was deepened by drilling down to 220 feet. Two new levels were drilled horizontally to reach the veins, one at 110 feet and the other at 201 feet.

Between in 1935-38, over 26 tons of ore were extracted and trucked to the mill at the Melville Mine. In 1934, the first significant shipment of Virginia gold concentrates to a smelter in 75 years was sent to American Metals Company in Parteet, New Jersey. 4,500 feet of core drilling below the 300-foot level revealed the ore body continued at depth.

However, the death of the president of the Rapidan Gold Corporation forced the company to sell its assets. The V-M Corporation took control and resumed mining at Vaucluse in 1935. It planned to drill the shaft deeper to 300 feet. Three shifts per day were put to work, but the challenge of pumping out the water limited progress to just one foot per day until reaching 300 feet.

By 1937, the Vaucluse Mine was operating with two shifts and producing 100 tons of ore per day. The mill at the Melville Mine was operating with three shifts per day, and the Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO) was supplying electricity to power all the operations.

A heavy rainstorm on April 24-25, 1937 flooded the mine. The pumps could not keep up with the inflow, and water filled the shaft and levels. The cost to bring in new pumps and restart mining was too high and V-M Corporation sold the land in 1938.9

In 1982, Callahan Mining Corporation drilled two exploratory holes on the site. In 1988, when Sterling Exploration Inc. requested a permit from the Orange County Planning Commission for more prospecting, the request was denied. By that time, the Lake of the Woods housing development had been completed south of Route 3. Residents objected to the possibility of an industrial mining operation just to their north.10

the 201-foot level of the Vaucluse Mine followed the vein

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Plan of the 201-foot level at Vaucluse Mine

The waste tailings and bedrock exposed due to mining resulted in "severe" acid mine drainage, as identified by state officials in 1988. Reclamation was not recommended at the time, because there was potential for re-opening the site for new mining operations.11

There are multiple health risks at old mine sites such as Vaucluse. Those concerns were raised when the Wilderness Crossing rezoning proposal in 2021 planned to construct over 4,000 housing units. The project would create surface disturbances at old gold diggings between Route 3 and the Rapidan River, including land around the Vaucluse Mine.

The voids of old shafts and levels create opportunities for people to fall in, and for the surface to collapse underneath new heavy buildings. A more widespread risk occurs when elemental mercury (Hg) left in the soil from the amalgamation process is converted by biological processes into methylmercury (CH3Hg). Methylmercury is highly toxic to growing embryos and human nervous systems. Humans are exposed today primarily by eating fish which acquired elevated levels through bioaccumulation at the top of the food chain. Whether or not the Wilderness Crossing project is ever completed, the mercury used in the past is still creating some level of elevated risk for people eating fish caught in the area.12