the bedrock exposed at Old Rag Mountain formed in the Grenville event roughly 1 billion years ago

Source: National Park Service, Shenandoah National Park, Geologic Resources Inventory Report

the bedrock exposed at Old Rag Mountain formed in the Grenville event roughly 1 billion years ago

Source: National Park Service, Shenandoah National Park, Geologic Resources Inventory Report

The universe is 13.8 billion years old, based on measurements of cosmic microwave background measurements. The oldest part of the Milky Way galaxy, the "thick disk" at the center, starting forming 13 billion years ago. The solar system is over 4.5 billion years old. It may have formed then after the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy collided with the Milky Way, bringing a new supply of hydrogen and disrupting the equilibrium enough to trigger another burst of star formation in the Milky Way.

The oldest objects ever found on earth are grains of silicon carbide found in the Murchison meteorite; they crystalized 7 billion years ago. The oldest rock on earth may be the Acasta Gneiss in Canada, west of Hudson Bay. It is 4.03 billion yeas old, and crystalized as the earth's crust transformed from magma ocean to hard rock. That change marks the end of the Hadean Eon and the start of the Archean Eon.

It is possible that even older rock is present on the eastern edge of Hudson Bay. Samples from the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt have been dated as 4.16 billion years old. If the date is accurate, the rock solidified soon after a collision with another planet (Theia) blasted the earth and melted whatever crust might have already solidified. Debris from earth and Theia scattered into space, then coalesced into the moon.

Based on a complex interpretation of uranium-lead ratios in zircons, the Watersmeet gneiss in Michigan at 3.6 billion years old is probably the oldest rock in the United States. The oldest rock in Virginia, the Nellysford gneiss found in Nelson County, has been a "Cheerio" of Virginia for 1.8 billion years. When that rock cooled into its current state, however, most of the bedrock in modern Virginia had not been created yet.1

By about 2 billion years ago - give or take a few hundred million years - various chunks of continental crust had clumped together with each other to create what is now the core of the North American continent. Today, we see those chunks exposed in the central part of Canada in what is called the "North American craton."

It may be easier to visualize tectonic plates as clumps of cereal (Cheerios, or Rice Krispies if you prefer...) floating in milk, rather than as chunks of continental crust floating on the molten mantle 25-50 miles below the surface.

About one billion years ago, another chunk of continental crust (more Cheerios...) banged into that craton. The North American plate was enlarged by the rocks that, today, form the oldest part of Virginia. (In the cereal analogy, some new-arriving Cheerios joined the North American craton.)

When those chunks of rock drifted together, the heat and pressure melted various rocks as the Grenville Mountains were uplifted. The igneous "roots" of those mountains consisted of ten or more different chunks of granite and gneiss.2

Source: EarthByte, Plate tectonic evolution from 1 Billion years ago to the present

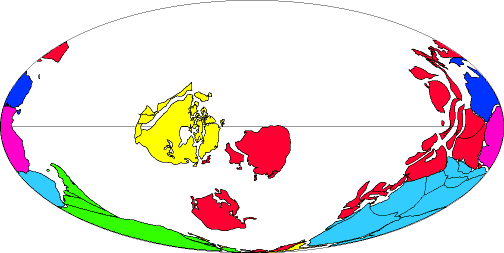

One billion years ago, essentially all the continental crust on the earth had clumped together and formed one supercontinent called Rodinia. Rodinia was surrounded by an ocean that covered most of the globe. (Think of a bowl of cereal where all the Cheerios are in one corner, and most of what you see is milk.)

Rodinia was at least the second supercontinent to form on earth, following a previous supercontinent known as Columbia. The next supercontinent will form 200-250 million years from now, creating Aurica or Amasia depending upon how the chunks consolidate.

There is an alternative description of how Rodinia formed. According to the single-lid hypothesis, the supercontinent could have been an unfragmented, all-encompassing lithosphere, a single "shell" of rock rather than a global plate mosaic. The assembled crust lasted as a unit for 600 million years, from 1.6 billion years ago to 1 billion years ago.

Virginia was in the middle of that Rodinia supercontinent, far from the seashore and far from rainstorms. The Virginia of a billion years ago had a "continental climate" comparable to today's Tibetan Plateau or the Gobi Desert in China/Mongolia.

The Grenville Mountains and the rest of Rodinia were barren. There were no trees or plants; there was no vegetation on the land yet. Algae photosynthesizing in the ocean had already transformed the atmosphere, poisoning most of the earliest forms of life with the waste product of photosynthesis - oxygen. However, the evolutionary process had not resulted in land plants yet, so a billion years ago all of Virginia was bare rock or lakes/rivers.

Even as the Grenville Mountains were pushed up by the collision of continental plates, rain was eroding the exposed rock. Rivers carved valleys, and sediments washed downstream to build shorelines. Up to 15 miles of rock eroded away, as uplifts were countered by erosion.3

What goes up must come down. In geology, what goes down will also come up. Today, erosion has exposed the once-buried-deep roots of the Grenville Mountains. At Shenandoah National Park, tourists can drive and hike on the igneous rocks that were formed over a billion years ago by continental plate collisions, and then buried miles below the surface.

Rodinia, roughly 1 billion years ago (Virginia is located in dark-brown belt of Grenville Mountains)

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Dr. Nicholas Short's Remote Sensing Tutorial

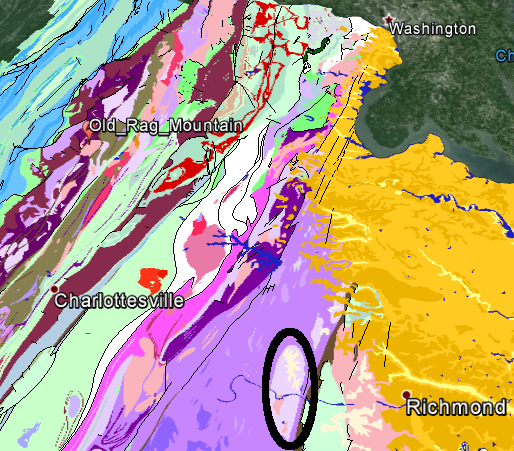

The Grenville Event - or events, because the mountains might have been created by multiple continental collisions - formed the "basement" rocks in Virginia. The heat and pressure of the collision(s) melted rocks, creating granite and gneiss. These crystalline rocks are now the core of the Blue Ridge mountains exposed in the Blue Ridge, including Old Rag Mountain in Madison County.

Grenville-age rocks (1.1-1.0 billion years old) are also exposed on the surface today as the State Farm granite, located northwest of Richmond and under the Virginia Correctional Center for Women in Goochland County. (The women's prison there includes an active dairy farm.)

the State Farm Granite (circled in black) is a part of the 1-bilion year old Grenville pluton

Source: Google Earth (with Geologic units of Virginia)

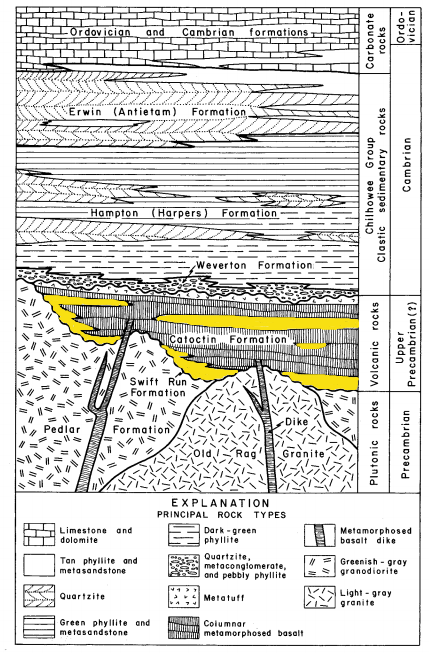

Erosion occurred throughout the Grenville orogeny (mountain-building uplift). As rocks were exposed, they immediately began to wash away. Today in Shenandoah National Park, the Swift Run Formation is a layer of sediments that were deposited on top of the ancient crystalline Grenville basement rocks.

Based on the thickness of the Swift Run Formation, erosion of the Grenville Mountains created roughly 2,000 feet of topographic "relief" (the difference between the mountain peaks and the valleys).4

That amount of relief is close to what you see today from the Skyline Drive, looking from the crest of the Blue Ridge west towards the Shenandoah Valley or east towards the Piedmont. The Skyline Drive is nearly 4,000 feet high in places... but the adjacent territory is also about 2,000 feet above sea level.

Roughly 400 million years after the Grenville Event, the continental plates pulled apart. The supercontinent of Rodinia had trapped too much heat, or perhaps the molten mantle underneath the crust bubbled a little (think of a spoon swirling the milk, pulling apart the clump of Cheerios). Multiple cracks formed in the crust of Rodinia, and then one developed as a "spreading center" with magma welling up in the middle of that crack.

The rising magma broke apart Rodinia, cracking it into multiple plates and pushing the North American plate away from the others. Debris from ridges on both sides of the crack eroded into the widening basin until, at some time, salty ocean water flowed in and a new ocean developed. Slowly, Virginia finally emerged on the coastline of the North American craton instead of being in the middle of Rodinia, smushed together with all the other continental plates.

That ocean is known as the Iapetus. In Greek myths, Iapetus was the father of Atlas. Since the Atlantic Ocean is named for Atlas, the ocean that existed before the Atlantic is called the Iapetus.

When the crust of Rodinia thinned and then cracked, the Grenville-era granitic rocks on the land were covered by a series of volcanic outpourings of basalt. The basalt flows that started as molten rock 40-70 miles below the surface erupted and coated the hard Grenville basement bedrock, plus the Swift Run sediments that had been previously deposited on the basement rock.5

(If you use a straw to blow air gently underneath the Cheerios in your bowl of milk, you can create equivalent eruptions of milk to coat the cereal.)

Some of the basalt lava on the east side of the Blue Ridge appears to have erupted under water. What water? It would have been the Iapetus Ocean, filling in one of the cracks that formed as the "Cheerios" of Rodinia drifted apart, or a temporary lake that formed in a great crack in the surface of the earth.

Basalt is a volcanic rock that is relatively low in quartz (silica), and can flow fast compared to silica-rich lava. The individual basalt flows in Virginia 600 million years ago may have moved at unusually rapid speed, as the magma shot up through the Grenville-age rocks and then flowed across the surface.

How do we know the speed of flow? The remaining dikes (the channels cut through the overlying sediments as magma moved up) are narrow. Slow-moving magma would have congealed and blocked those channels before transmitting enough molten rock to create the broad expanses of Catoctin basalt.

Swift Run Formation (highlighted in yellow) - old sediments deposited on top of "basement" rocks and then buried 600 million years ago by Catoctin basalts

Source: Geology of the Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Bulletin 86 (Figure 6 on p. 11)

The Grenville-age hills and valleys were covered by about 2,000 feet of basalt, leveling much of the landscape in what became Shenandoah National Park.6

At roughly the same time as the basalts were erupting, a volcano spewed a vast amount of lava near what became the North Carolina border. Later, that hard volcanic rock would be buried and exposed again by erosion to become Virginia's highest point, Mount Rogers. The Catoctin basalt would also be buried and metamorphosed by heat and pressure, realigning atoms and creating new minerals. Today, there is so much epidote (a green mineral) in the metamorphosed basalt that it its known as "greenstone."

Old Rag mountain (exposed billion-year old "basement") in Shenandoah National Park

If you hopped in a time machine and went back 600 million years to stand at Old Rag Mountain in Shenandoah National Park and looked towards what is now West Virginia, you would see a flat plain of black volcanic rocks. If you looked in the other direction, you would see Iapetus Ocean waves crashing at the base of the volcanic rocks. What today is Richmond would have been underwater.

Also, you would not be looking west towards the flat plain, or east towards the Iapetus Ocean. Virginia was twisted 90 degrees from the present orientation, "aligned parallel to the equator that passed through the central part of the United States, roughly coincident with the present-day longitude of Kansas." Virginia was south of the Equator 600 million years ago, when the Catoctin lavas erupted and covered the billion-year old Grenville bedrock. The future Shenandoah Valley lay to the north of the future Blue Ridge Parkway, and the coastline of the Iapetus Ocean lay to the south.7

at the start of the Cambrian Period 590 million years ago, North America (in yellow) was on the equator and Virginia was on the southern - not eastern - edge of the continent

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Color-coded Continents!

Don't stop now - keep on going....

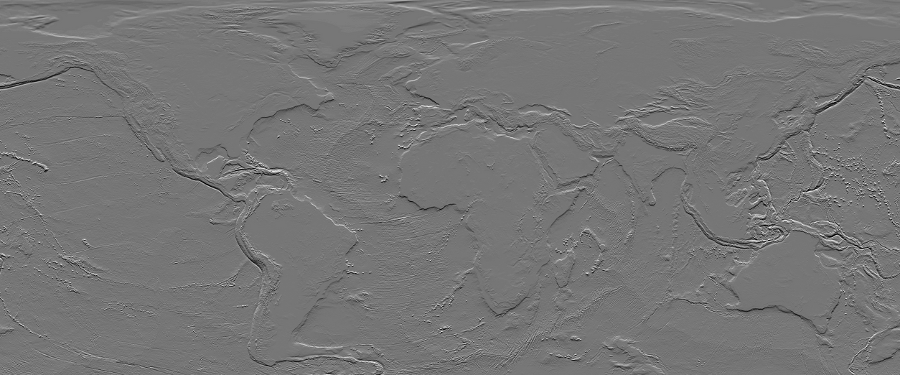

continental crust is has more silica and lower density, so it floats higher than the iron-rich basaltic crust that forms the seafloors and creates tectonic plates that move, collide, and form mountain ranges

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, GLOBE: A Gallery of High Resolution Images