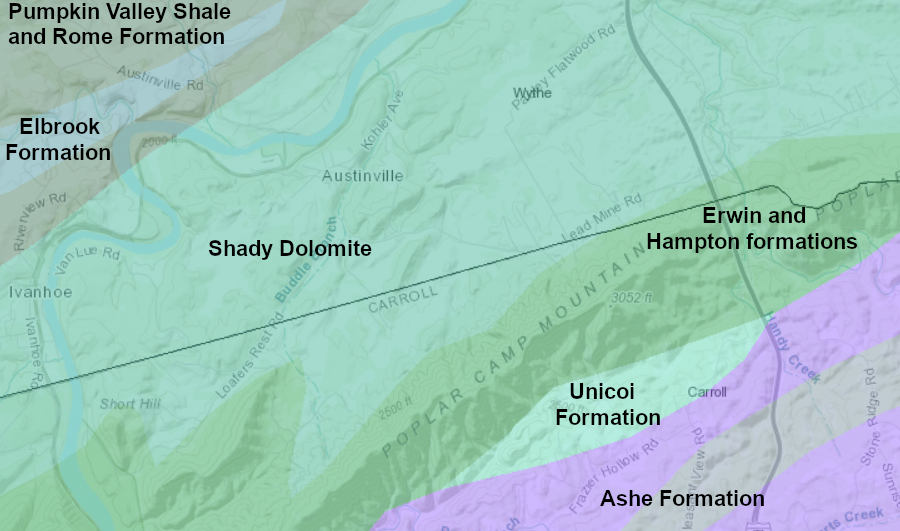

lead ore at Austinville is found within the Shady Dolomite

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Geology Mineral Resources

lead ore at Austinville is found within the Shady Dolomite

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Geology Mineral Resources

Once colonists brought guns that needed lead bullets to Virginia, there was a market for mining lead (Pb). The first lead ore deposit to be developed was in Austinville. Mining started there in 1750 and lasted until 1981.

Austinville in Wythe County was the first and last place where lead was mined commercially in Virginia. As described by Virginia Energy:1

Lead was also mined in Albemarle County, where the Faber Mine was discovered in 1849. During the Civil War the Faber Mine produced 7,000 pounds of lead. Between 1906-1919, lead and zinc ore were extracted with silver as a secondary product.

The Faber miners found sphalerite (Zn,Fe)S and galena PbS within lenses of fluorspar CaF2. The sphalerite and galena had been deposited when hydrothermal fluids intruded into the metasedimentary rocks of the Lynchburg Formation. The sediments were metamorphosed roughly 500 million years ago when the lavas of the Catoctin Formation reached the surface. The fluorspar/flourite could be used as a flux that removed impurities, such as sulfur, when metallic mineral ore was smelted.

The Albemarle Zinc and Lead Company reopened the Faber Mine in 1906. The vein averaged four feet wide. Three shafts were sunk to 25', 50', and 120' deep.2

Lead veins at Austinville and Faber are Mississippi Valley-type deposits. Fluids rich with dissolved lead and zinc were produced as seawater evaporated in a basin. Tectonic shifts then forced high-temperature hydrothermal fluids through limestone/dolomite formations in which the lead ore was deposited.

Unlike gold and copper deposits in Virginia, the hydrothermal fluids that concentrated lead in the Austinville and Faber deposits were not associated with magma or volcanic events. The two largest lead mining districts in Virginia are not "skarn" deposits, and were not formed when a magma body intruded into carbonaceous sedimentary rocks.

In contrast, the lead present in the Great Gossan Lead District, in Carroll and Grayson counties in Virginia and extending into North Carolina, is part of a massive sulfide deposit related to submarine volcanism. Lead is a secondary mineral found in various massive sulfide deposits, such as the Tungsten Queen Deposit in the Hamme District of Mecklenburg County and North Carolina.3

In Mississippi Valley-type deposits:4

"Skarn" deposits of lead ore has also been identified in the Chopawamsic Terrane, which accreted to Laurentia as Pangea formed. Major deposits of gold, iron, and pyrite have been mined from the metamorphosed remnants of one or more volcanic island arcs that formed in the Iapetus Ocean around 500 million years ago. Minerals were first differentiated from magma and concentrated as lava neared the surface at the island arc, creating syngenetic mineral deposits. The minerals were later heated, remobilized, and distributed by hydrothermal fluids, forced into faults and fissures during orogenies as Pangea formed to create orogenic mineral deposits.

Ore removed from the Valzinco Zinc Mine in Spotsylvania County included 7.8% zinc and 3.7% lead. Shafts were driven to 300' deep. The vein was about 10 feet thick and stretched for 30 miles.

Commercial mining by the Berthea Mineral Company occurred in 1909-1912. The Virginia Lead and Zinc Company operated the mine during World War I in 1914-1918, and again in 1927. Panaminus reopened the Valzinco Zinc Mine during World War II. The company built a mill that could process 100 tons per day in 1942. Mining stopped in 1945, when the end of the war reduced demand.5

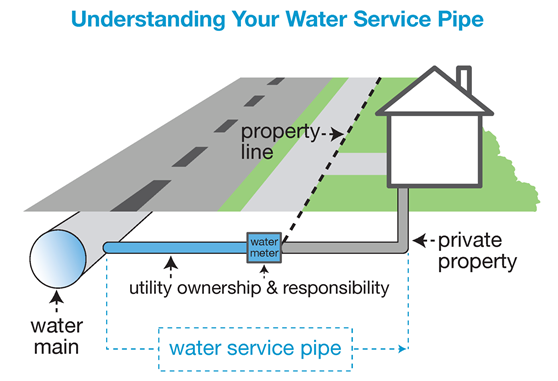

Lead is a neurotoxin that damages the human nervous system. The Maximum Contaminant Level Goal established by the Environmental Protection Agency is zero. However, The Federal agency's "action level" was set at 0.015 mg/liter. That threshold required public water systems to adjust their water treatment process, if they produced water corrosive enough to dissolve lead and lead solder in pipes and ended up delivering water above the action level.

There is a "safe" level of lead in drinking water. According to the World Health Organization:6

Tetraethyllead with the chemical formula Pb(C2H5)4 was added to gasoline as a fuel additive soon after cars became widespread in the 1920's. The lead additive increased the octane rating and reduced engine "knocking," and Richmond-based Ethyl Corporation was a major producer. Car exhaust distributed toxic lead residue widely, so Federal regulations required lead-free gasoline starting in the 1970's and finishing in 1996.7

Lead in paint was another major cause of exposure, affecting in particular infants and disadvantaged communities with older housing units. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that over half of children in the United States were at risk of lead exposure. Children were thought to be getting poisoned by eating paint chips flaking off the walls, but the major avenue of exposure occurred during renovations that created microscopic dust with lead that was inhaled or ingested.

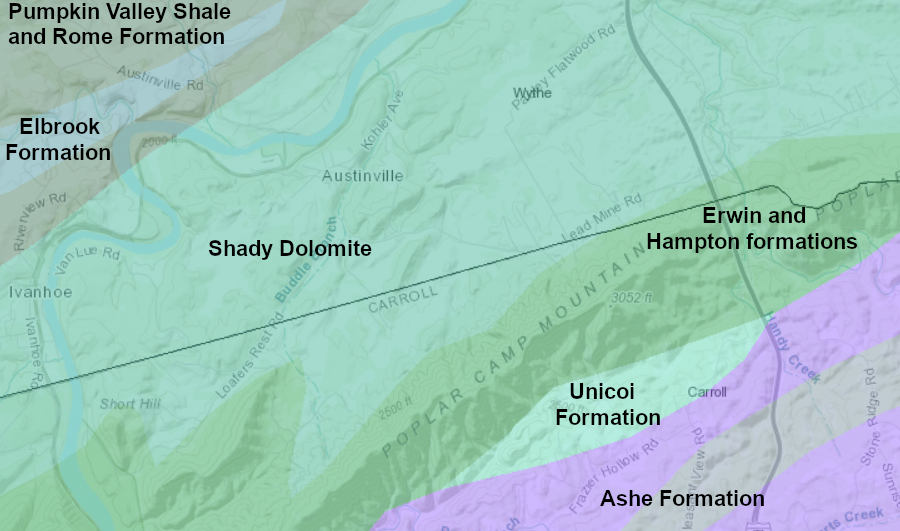

The Biden Administration issued its Lead Pipe and Paint Action Plan in 2021. Funding for lead paint removal from 24 million housing units was included in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.8 Water pipes containing lead were the last major source of lead to be addressed in order to improve human health. Installation of new lead pipes in houses stopped in 1986, but by 2024 there were still 9,000,000 houses in the United States with older pipes containing lead. In 2023, EPA's Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment (DWINSA) estimated that there were 187,883 lead service lines still in use in Virginia.Public drinking water systems are responsible for pipes that lead from the treatment plant to the meter at each building. From the meter to the building, and inside the building, pipes are privately owned.

in the distribution system of drinking water, public ownership of the pipes stops at the water meter

Source: Wythe County, Water Service Line Survey

The threat of lead pipes became widely known after the city of Flint, Michigan switched its source of water in 2014. Water from the new source was more corrosive, and it etched lead from pipes as water flowed to houses. Marc Edwards, a professor at Virginia Tech, exposed the dangerously high levels of lead. and the government malpractice at Flint became national news.

The Virginia Department of Health offered Lead Elimination Assistance Program (LEAP) grants to fund removal of lead service lines starting in 2017, with funding that would enable a very gradual replacement process. The $2 million per year allocated to public drinking water systems for lead pipe inventory and replacement was supplemented by the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which provided an additional $45 million per year between FY2022 through FY2026.

On October 8, 2024, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued its final Lead and Copper Rule Improvements rule, which had first been published in 1991 and revised in 2000 and 2007. EPA lowered the action level for lead in drinking water from 15 µg/L to 10 µg/L.

The 2024 rule required public drinking water systems to identify and eliminate all lead and copper service lines within 10 years. Nationwide, the cost (including removal of privately-owned pipes between water meters and houses, and within houses) would cost between $28 billion and $47 billion.9

Piston-driven engines have a high compression ratio and use AVGAS 100 or 100LL with a 100-octane fuel number, thanks to the inclusion of tetra-ethyl lead as an additive. The additive prevents preignition when fuel is injected into the hot combustion chamber.

A public-private partnership is planning the transition to lead-free aviation fuels for piston-engine aircraft by the end of 2030. The Eliminate Aviation Gasoline Lead Emissions (EAGLE) initiative is intended to lower the risks of lead exposure to communities adjacent to general aviation airports. Airports will need to install additional fuel tanks to offer lead-free gas during the transition, and owners of existing aircraft with a standard airworthiness certificate will have to have a certificated mechanic or authorized entity alter the type certificate/supplemental type certificate.10

Source: Virginia Humanities, The Chiswell Lead Mines during the Revolution

people are exposed to toxic lead through drinking water pipes installed before 1986

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Getting Started with Lead Service Line Identification and Replacement