Virginia Diamonds

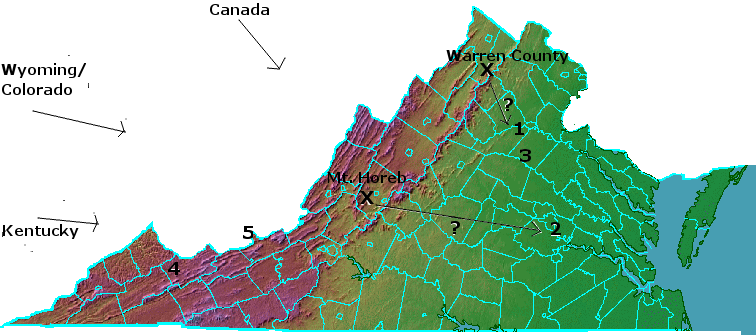

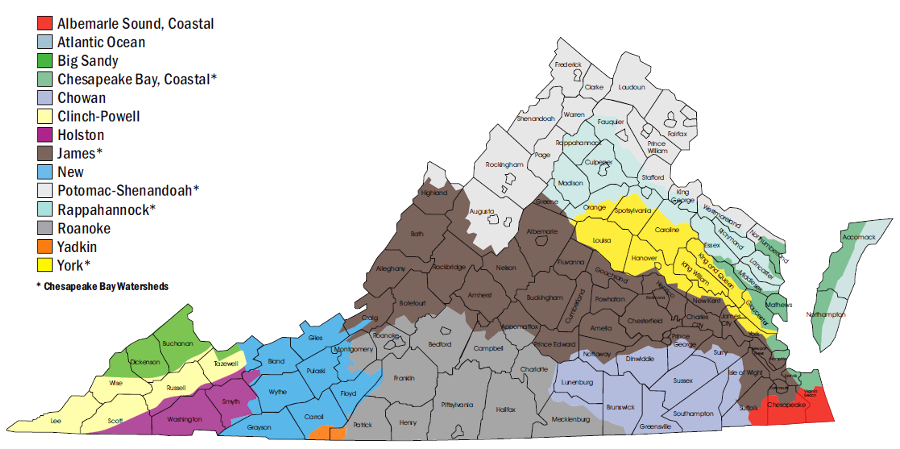

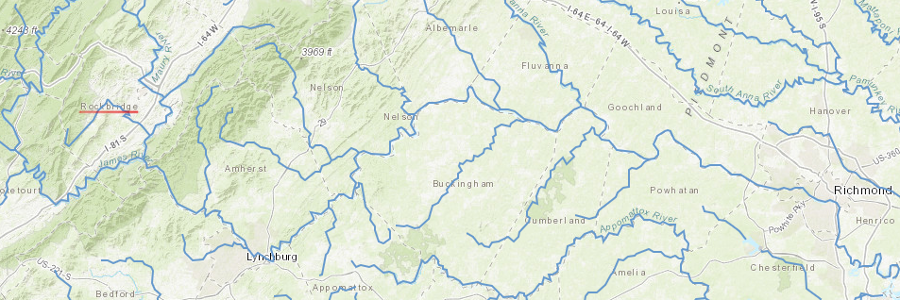

approximate locations of Virginia diamond finds and potential source rocks:

- Front Royal (Warren County) peridotite: potential source for Vaucluse Mine, Orange County (1) and Whitehall Mine, Spotsylvania County (3) diamonds

- Mount Herob (Rockbridge County) kimberlite: potential source for Dewey Diamond (2)

- those sources, or perhaps Kentucky kimberlites, Arkansas pyroclastic lamproite tuff, or Wyoming/Canadian kimberlite pipes could be the sources for the Tazewell County (4) and "Punch Jones" (5) diamonds

Source: derived from Virginia Division of Mineral Resources, Diamonds

After the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago, hydrogen atoms fused inside stars and formed elements up to iron. When a star exploded as a supernova, a gas cloud was created - and as the cloud cooled:1

- [t]iny crystallites of pure carbon - diamond and graphite - were probably the first minerals in the universe.

50 young stars, all of them similar in mass to the Sun or smaller, and associated planetary systems can be seen forming now in the Rho Ophiuchi cloud complex

Source: Webb Space Telescope, Webb Celebrates First Year of Science With Close-up on Birth of Sun-like Stars

Meteorites still bring microscopic and occasionally larger black diamonds (carbonados) to earth from those star clouds. In Russian there is a ring of tiny diamonds around the edge of the Popigai impact crater. When an asteroid struck the earth there about 35 million years ago, pressure waves moving through the crust converted flakes of graphite in the bedrock into small crystalline diamonds.

All diamonds found in Virginia appear to have been formed here on earth through natural geological processes. Because no source rocks with diamonds have been identified in Virginia, the two primary mysteries are:

- where did they originate?

- how did they get to Virginia?

Four diamonds have been found within the current boundaries of Virginia:

- - at the Vaucluse Mine in Orange County (1836)

- - at Ninth and Perry streets in Manchester, now part of the City of Richmond (1854)

- - at the Whitehall Mine in Spotsylvania County (around 1878)

- - near Pounding Mill in Tazewell County (1913)

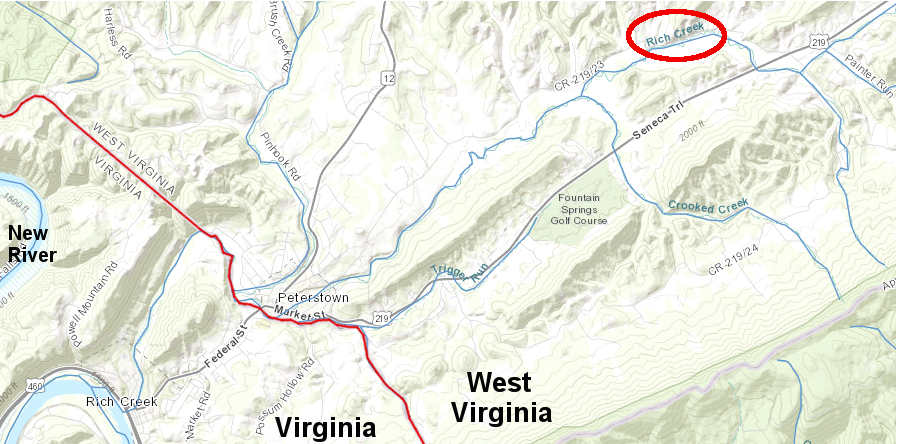

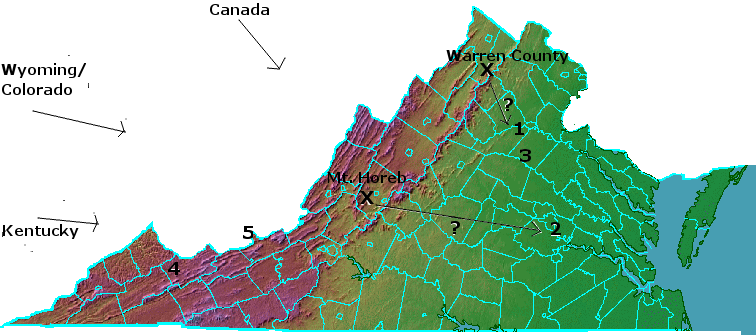

A fifth diamond was found in 1928 on Rich Creek near Peterstown, West Virginia, just across the state border from Giles County. It is known as the "Punch Jones" diamond.

William "Punch" Jones and his father recognized the shiny rock was different from others nearby while pitching horseshoes. They picked up the curiosity and put it into a box at their home. During World War II, "Punch" Jones was making gunpowder at the Radford Army Ammunition Plant. He realized that the carbon used to make gunpowder could also be formed into a diamond. In 1943, he took his old stone out of the box and brought it to a geologist at Virginia Polytechnic Institute (now Virginia Tech) for identification.

The geologist, Dr. Roy J. Holden, proposed it could be a "Virginia" diamond even though the gem was found in West Virginia. "Punch" Jones picked it up at a spot just uphill from the Virginia boundary. Impact marks suggested it could have eroded out of Virginia bedrock and washed down the New River in a flood. If the waters and flood debris had backed up into Rich Creek, then the diamond could have been carried by the floodwaters across what later became the state line and deposited in alluvium.2

the "Punch" Jones diamond was found in Rich Creek, upstream from the Virginia border

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

It is also possible that the four diamonds found in Virginia, as well as the Punch Jones diamond, were created in a source rock located far from where the diamonds were found. The "Dewey" or "Manchester Diamond" was found in Manchester/Richmond, but it could have been created through ancient geologic processes in a place outside of the James River watershed and even on the other side of the Mississippi River.

Most diamonds are ancient; they formed around one to three billion years ago. That was long before land plants developed, so Virginia's diamonds were not created by compressing coal under great pressure.

Diamonds crystalize in the mantle, below the crust-mantle boundary, in a zone about 75-100 miles underground. Some diamonds may have crystallized several hundreds of miles deeper in tectonic subduction zones.

When supercontinents such as Rodinia and Pangea break up, convection currents from the mantle can break off slabs of continental "roots." As that material sinks into the mantle, the extraordinary heat/pressure can convert carbon within the crustal rocks into diamonds. The diamonds may stay at the base of the continents for hundreds of millions of years, even for billions.

If the right amount of gas and water is present, those diamonds get mixed with volcanic magma called kimberlite and shoved up to the surface under pressure. A "pipe" of kimberlite can move upwards when there is enough water in the deep molten rock to reduce viscosity so atoms can move freely, and enough carbon dioxide gas to push the molten rock past the Moho boundary separating the crust from the mantle. Without strong pressure from expanding gas as a plume rises, rock from the mantle cools at the base of the crust and becomes too dense to come near the surface.

The earth appears to have cooled too much now to support eruptions that bring diamonds up from the deep mantle, but the more-shallow eruptions can still occur as a part of the supercontinent cycle.

diamonds are carried along for the ride when kimberlites rapidly climb to the surface

Source: James St. John, Diamond in kimberlite

Kimberlite eruptions appear to reach the surface around 22-30 million years after supercontinents split up, and after slabs of crustal roots have migrated away from the edges of continental plates. Diamond prospectors are now identifying new places to search, based on the recent theory that the rare eruptions with diamonds occur within the interior of tectonic plates rather than on the edges.

Plate tectonics is still delivering slabs of carbon-rich rocks deep enough into the crust and mantle, perhaps to places where heat/pressure will create new diamonds. Future volcanoes on island arcs above subduction slabs could bring new diamonds to the surface, if a somewhat shallow mantle plume is triggered again.

A diamond's trip to the surface is a rare process. Diamonds rise from the mantle and then the crust through narrow volcanic "pipes," moving as much as 11-83 miles per hour and rising roughly 100 miles in less than 2 days. The climb to the surface takes diamonds (and the molten kimberlite rising up with them) through changing zones of heat and pressure, from a deep source to a volcanic eruption on the surface.

Recrystallization (resorption) of the atoms in a diamond into another mineral form would occur if that trip to the surface was slow. Diamonds survive only when the lift to the surface is completed quickly. A rapid trip does not give the crystals time to oxidize into graphite/carbon dioxide, which would alter the alignment of the carbon atoms and molecules. A diamond crystal often captures inclusions between the carbon molecules, so diamonds provide geologists a rare opportunity to examine tiny samples of minerals that normally exist only in the deep mantle.

For example, the first evidence of a high-pressure calcium silicate perovskite (CaSiO3), a mineral named "davemaoite," was discovered as an inclusion in a Botswana diamond that originated over 400 miles deep. That mineral had never been seen before because, when the davemaoite moves towards the surface, the molecules realign into different minerals as pressure decreases:3

- The discovery of davemaoite shows that diamonds can form farther down in the mantle than previously thought.

Diamonds also can be formed by high-speed collisions, including astronomical impacts on earth. Impacts in space can create diamonds within meteorites, which then collide with the earth in places that may be far from kimberlite pipes. The gem market can also be affected by laboratory scientists and industrial engineers who manufacture artificial diamonds, using machines that put carbon molecules under great heat and pressure.

Source: Beyond4cs.com

In 1564, French explorer Jacques Cartier thought he had found diamonds on the St. Lawrence River where Quebec City was founded. The crystals that he collected were examined in France and declared to be worthless quartz. The fraudulent claim gave rise to the phrase: "Faux comme un diamant du Canada" or "Fake as a Canadian diamond."4

There are two potential sources within Virginia where the four diamonds found within Virginia's borders could have erupted originally onto the surface of the earth. There is a kimberlite pipe in Rockbridge County near Mt. Horeb Church, and a mica peridotite dike in Warren County.

It is possible that future geologists may discover other locations with the distinctive volcanic features associated with diamond delivery from the mantle. Eruption associated with the failed rifting of Rodinia 750 million years ago may have included plumes from the core-mantle boundary which brought yet-to-be-found diamonds to the surface. Near Mount Rogers or South Mountain in Pennsylvania, which formed during a failed continental rifting before Pangea finally broke up, there may be more undiscovered kimberlite pipes.

More recent Eocene epoch eruptions at Trimble Knob (Highland County) and Mole Hill (Rockingham County) are diatremes, which are volcanic pipes but not kimberlites. According to current geologic interpretation, diatremes less than 50 million years old are too young to be source rocks for diamonds.

a kimberlite pipe has been identified near Mt. Horeb Church in Rockbridge County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Less than 1% of kimberlite pipes bring gem-quality diamonds to the surface, and none of the diamonds found in Virginia are in Rockbridge or Warren counties near the two potential in-state sources. The diamonds found in Virginia could have been brought to the surface in what is now Kentucky, Arkansas, the Wyoming/Colorado border, or in Canada.

The largest diamond ever found in the United States, the "Uncle Sam," came from what is now Crater of Diamonds State Park in Arkansas. The Murfreesboro lamprophyre was emplaced there roughly 100 million years ago. The diamonds with that rock may have formed

5

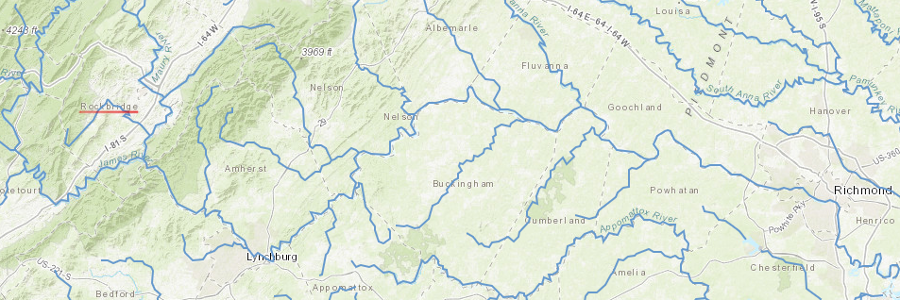

All Virginia diamonds were found in unconsolidated sediments, rather than in their original geologic context. They were carried by water and deposited downstream from their original location. The Dewey Diamond found in Manchester/Richmond could have been washed from the Rockbridge County kimberlite pipe down the James River. In 1942, the state geologist stated that it:6

- must either have been brought down the James River and deposited with some of its sediments, or have been introduced accidentally by man into these stream deposits.

a diamond from the kimberlite pipe in Rockbridge County could have washed down the James River to Richmond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

No one claimed they had somehow lost that distinctive "pebble" - after all, it was not a cut stone with regular facets. Still, since it was found in a well-traveled location, one possibility is that someone had picked up an unusual rock in Kentucky, Arkansas, the Wyoming/Colorado border, or in Canada, and the unusual rock fell out of a person's pocket the night before while they crossed the street in the city.

The Dewey Diamond was a 23.75 carat raw stone when found in six feet of clay by a laborer leveling the road. The laborer, Benjamin Moore, sold the rock to Captain Samuel Dewey, a gemologist in Philadelphia. He had the stone cut to less than half of its original 23.75 carat size in an effort to eliminate an imperfection, and Dewey's name is associated with the jewel.

One wild speculation on how that diamond ended up at the Fall Line, far from any known kimberlite or lamprophyre source rocks, was published in the Richmond Times-Dispatch in 1910. The story claimed that the stone had been recognized as unique by Native Americans and buried with an Indian chief. The road clearing had excavated the grave and revealed the special grave object.7

The Warren County peridotite dike could be the original source for the diamonds found in Orange County, Spotsylvania County, and in Manchester/Richmond. They may have eroded out of that dike and been transported east, around 100 million years ago. When the Potomac Formation was deposited during the Cretaceous Period, diamonds could have been part of the sediment load eroded from the dike and washed downstream to the shoreline of the Atlantic Ocean. At the time, there was no Blue Ridge barrier; it was not yet exhumed, and not a topographic feature on the landscape.

If Warren County is the source, then erosion and transport must have occurred before the Potomac River cut its gap through the Blue Ridge five million years ago at Harpers Ferry. Glaciers at the end of the "Snowball Earth" period, around 600 million years ago, may have brought the diamonds from a far-distant source. More-recent glaciers, those that created the Great Lakes, would have not been able to carry any Warren County diamonds into the watersheds of the Rappahannock or James rivers.

About five million years ago, after the Potomac River breached the Blue Ridge, its tributaries began to carve deeper channels and "pirate" streams west of the mountains. The Shenandoah River intercepted streams that had previously flowed eastward through Blue Ridge gaps. As the Shenandoah River expanded its valley further south, any diamonds in Warren County would have been washed downhill by the Shenandoah River towards the Potomac River.

If eroded from Warren County in last few million years, diamonds would have been deposited as part of alluvial sediments within the Potomac River watershed. No diamonds moved from the Shenandoah River watershed since soon after the Harpers Ferry water gap formed would have ended up in Manchester/Richmond, at the Vaucluse Mine in Orange County, or at the Whitehall Mine in Spotsylvania County.

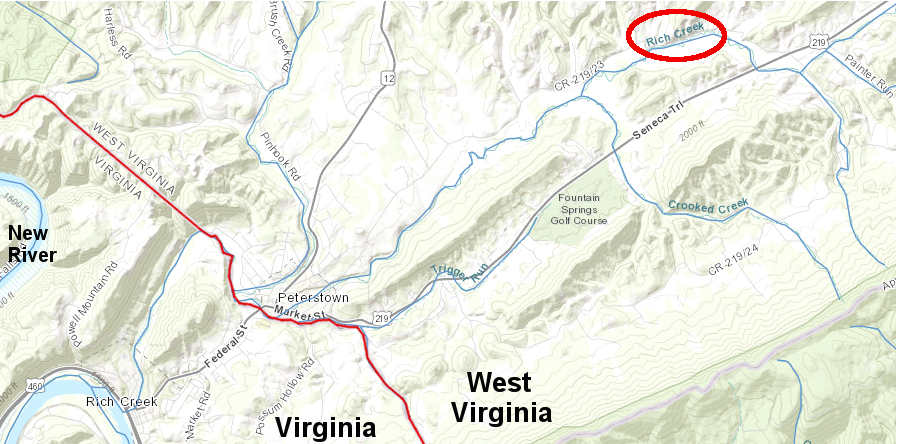

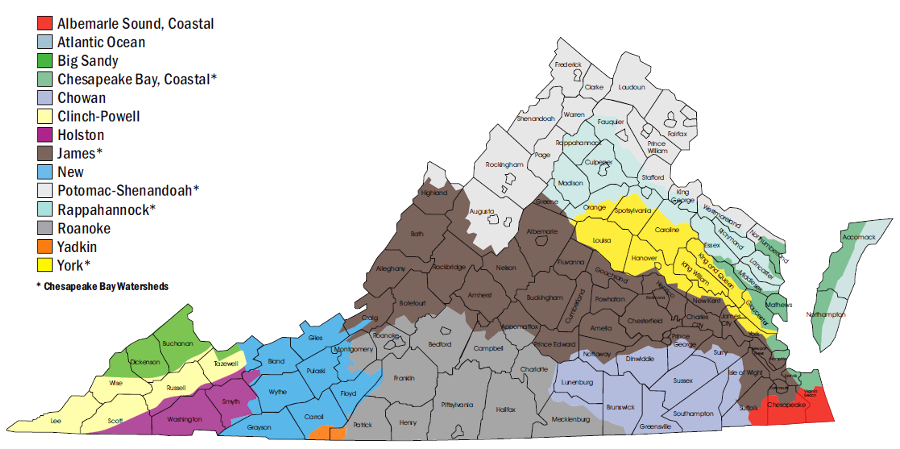

any diamonds transported from Warren County in the last few million years would have been deposited in the Potomac River watershed

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Virginia's Major Watersheds

There may be more diamonds discovered in Virginia.

Between 1893-2014, 13 diamonds had been discovered in North Carolina. In 2014, the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences concluded that 10 stones brought for assessment by an amateur geologist from Mount Pleasant, North Carolina were natural diamonds. He had adjusted his gold-mining equipment to trap diamonds, and apparently succeeded.

The geologist/miner died before he had an opportunity to show the location from which the diamonds were collected. The source rock of the North Carolina gems may be kimberlite or lamproite, but its location remains a mystery.8

The five different finders of diamonds in Virginia recognized they had unusually-glittering pebbles. Raw diamonds do not have the brilliant sparkle of a diamond in a modern ring, which is accentuated by the style in which the raw stone is cut. An article in the 1859 Harper's New Monthly Magazine noted about the Dewey Diamond:9

- The great marvel in this Virginia diamond is not that it was found, but that it was retained by the finder; for were it dropped among the pebbles at Cape May or Newport, it would have been among the last to be elected as being "so like a diamond."

the Dewey Diamond discovered in Manchester (now part of Richmond) may have been transported there from halfway across the North American continent

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The "Punch" Jones diamond was stored in a cigar box for 14 years before being identified. That 34.5 carat diamond is now considered to be the largest diamond discovered in alluvial sediments, and the third largest diamond overall, ever discovered in North America.

The diamond was loaned to the Smithsonian for display in 1944, where it stayed until 1968. "Punch" Jones ended up in Europe with the US Army and died in battle on April, 1, 1945, as American troops were crossing the Rhine. In 1984, the diamond was sold at auction at Sotheby's to someone representing an unknown buyer in the Orient, with proceeds used to pay medical costs for "Punch" Jones's mother.

Three of the other Virginia diamonds had been sold and can no longer be traced. As of 1997, the diamond found southeast of Richlands in Tazewell County was still owned by the family on whose farm it was discovered.10

diamonds travel through kimberlite pipes and arrive as intact crystals on the surface

Source: Flickr, Diamond in kimberlite

Links

- American Museum of Natural History

- Arkansas Geologic Survey

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas

- Kentucky Geological Survey

- Milwaukee Sentinel (August 18, 1944)

- National Geographic

- Nature

- NOVA

- Radford University

- Smithsonian

- Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy

- Washington Post

- Wyoming State Geological Survey

References

1. Robert M. Hazen, The Story of Earth: The First 4.5 Billion Years, From Stardust to Living Planet, Penguin, 2013, p.12, https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Story_of_Earth.html?id=orKKDQAAQBAJ (last checked May 20, 2018)

2. "Jones Diamond," e-VVV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia, May 19, 2016, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1049; "William Pinkney Jones

1917-1945," West Virginia Veterans Memorial, http://www.wvculture.org/history/wvmemory/vets/joneswilliam/joneswilliam.html; "Russia's Crater of Diamonds," NASA Earth Observatory, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148403/russias-crater-of-diamonds; "Diamonds Beneath the Popigai Crater - Northern Russia," Geology.com, https://geology.com/articles/popigai-crater-diamonds/ (last checked December 14, 2024)

3. David A. D. Evans, "Earth science: Proposal with a ring of diamonds," Nature vol. 466, pp.326-327 (15 July 2010), doi:10.1038/466326a, http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v466/n7304/full/466326a.html; Richard A. Lovett, "How Diamond-Studded Magma Rises From Earth's Depths," National Geographic, January 19, 2012, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/01/120119-diamonds-gems-earth-magma-carbonate-rocks-science/; Cate Lineberry, "Diamonds Unearthed," Smithsonian, December 2006, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/diamond.html; "How Do Diamonds Form?," Geology.com, https://geology.com/articles/diamonds-from-coal/; "Diamonds Show Depth Of Earth's Carbon Cycle," Carnegie Institution for Science, September 15, 2011, https://carnegiescience.edu/news/diamonds-show-depth-earth%E2%80%99s-carbon-cycle; "Confirmed: Earth Is Crushing the Ocean into Salty Diamonds," LiveScience, May 29, 2019. https://www.livescience.com/65589-diamonds-come-from-the-sea.html; Andrew H. Knoll, A Brief History of Earth, Custom House, 2021, pp.22-23, https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Brief_History_of_Earth/_T7yDwAAQBAJ; "Diamond hauled from deep inside Earth holds never-before-seen mineral," Live Science, November 11, 2021, https://www.livescience.com/new-mantle-mineral-found-in-diamond; "We've discovered how diamonds make their way to the surface and it may tell us where to find them," The Conversation, July 26, 2023, https://theconversation.com/weve-discovered-how-diamonds-make-their-way-to-the-surface-and-it-may-tell-us-where-to-find-them-210421; "Fountains of diamonds erupt from Earth's center as supercontinents break up," LiveScience, August 18, 2023, https://www.livescience.com/planet-earth/geology/fountains-of-diamonds-erupt-from-earths-center-as-supercontinents-break-up; Thomas M. Gernon et alia, "Rift-induced disruption of cratonic keels drives kimberlite volcanism," Nature, Volume 620 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06193-3; "Scientists discover the substance that brings diamonds 93 miles up to Earth's surface," Earth.com, November 30, 2025, https://www.earth.com/news/scientists-discover-kimberlite-brings-diamonds-93-miles-up-to-earths-surface/ (last checked December 1, 2025)

4. "Diamonds of Canada," The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/diamonds-of-canada last checked August 14, 2021)

5. Palmer C. Sweet, "Diamonds in Virginia," Virginia Department of Energy, https://www.energy.virginia.gov/commerce/ProductDetails.aspx?productID=2712; "How Diamonds Are Formed," Cape Town Diamond Museum, http://www.capetowndiamondmuseum.org/about-diamonds/formation-of-diamonds/; "Crater of Diamonds State Park," Encyclopedia of Arkamsas, https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/crater-of-diamonds-state-park-11/; "Discovering Lamproite at the Crater," Arkansas State Parks, June 20321, https://www.arkansasstateparks.com/articles/discovering-lamproite-crater (last checked August 3, 2025)

6. "What Do You Wish To Know," Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 18, 1942, p.53

7. "Daily Queries and Answers," Times-Dispatch (Richmond), November 9, 1910; Palmer C. Sweet, "Diamonds in Virginia," Virginia Department of Energy, https://www.energy.virginia.gov/commerce/ProductDetails.aspx?productID=2712 (last checked August 3, 2025)

8. "NC Mineral Resources - An Overview," North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, https://deq.nc.gov/about/divisions/energy-mineral-land-resources/north-carolina-geological-survey/mineral-resources/mineral-resources-faq; "Ten New North Carolina Diamonds," North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, December 4, 2014, https://naturalsciencesresearch.wordpress.com/2014/12/04/ten-new-north-carolina-diamonds/; "Part II- Ten New Diamonds from NC," North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, December 9, 2014, https://naturalsciencesresearch.wordpress.com/2014/12/09/part-ii-ten-new-diamonds-from-nc/ (last checked May 17, 2018)

9. Harper's New Monthly Magazine Volume 0019 Issue 112 (September 1859) / Volume 19, Issue: 112, September 1859, pp. 466-481, http://digital.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=harp;idno=harp0019-4 (last checked May 22, 2012)

10. Palmer C. Sweet, "Diamonds in Virginia," Virginia Department of Energy, https://www.energy.virginia.gov/commerce/ProductDetails.aspx?productID=2712; Dave Tabler, "I wish they'd a threw it in the New River sometimes," Appalachian History, May 4, 2018, http://www.appalachianhistory.net/2018/05/i-wish-theyd-threw-it-in-new-river.html (last checked August 3, 2025)

in Siberia, massive amounts of rock are extracted from the mine at the Udachnaya pipe to find a few diamond crystals

Source: Wikipedia, Diamond

Rocks and Ridges - The Geology of Virginia

Virginia Places