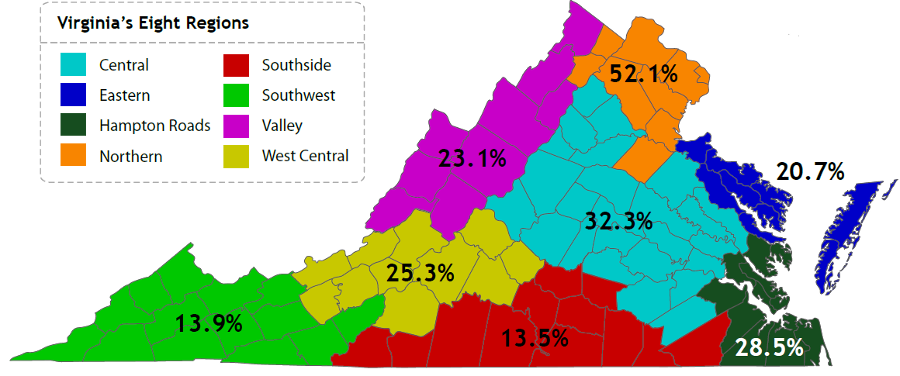

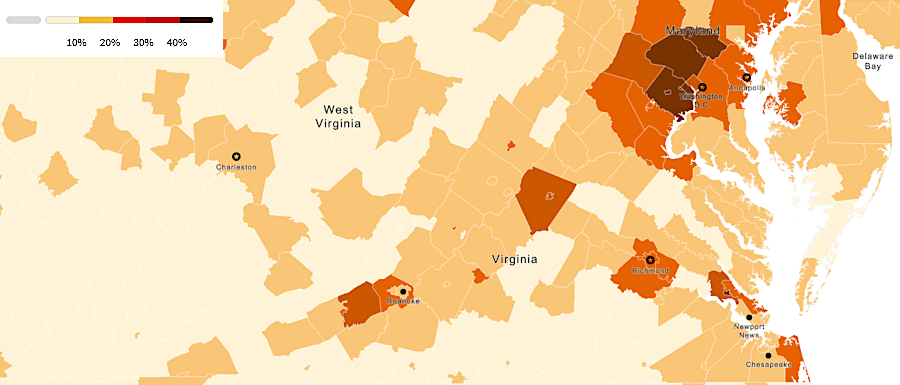

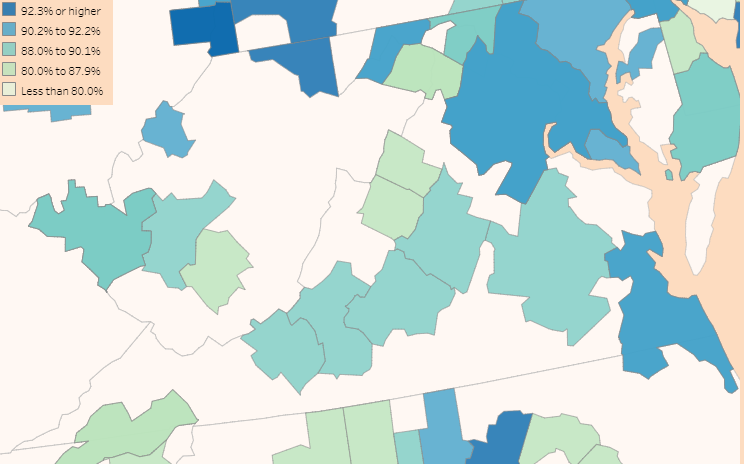

the contrast between educational attainment in Northern Virginia vs. Southside or Southwestern Virginia is clear

Source: Governor of Virginia, New Virginia Economy (December 2014, p.5)

the contrast between educational attainment in Northern Virginia vs. Southside or Southwestern Virginia is clear

Source: Governor of Virginia, New Virginia Economy (December 2014, p.5)

In colonial and pre-Civil War Virginia, education was the responsibility of the family rather than the government. There were no public schools, no school buses, and school boards, no Department of Education - and no debates over modifying school boundaries or where o build new schools in suburbs where the population is growing.

The English who arrived at Jamestown in 1607 included educated gentlemen. The Reverend Robert Hunt provided them some moral philosophy education through his sermons, even after his library burned in January, 1608. However, book learning was not a priority in colonial Virginia. The first colonists received a more-valuable practical education from the Algonquians (and the school of hard knocks) on how to survive in the New World.

It took 11 years after arriving at Jamestown for the English to establish the first public school in Virginia; the "Colledge" of Henricus was chartered in 1618. It was intended to educate both colonists and Native Americans, as part of the colonial policy to assimilate them into English culture. The proposed school was financed by contributions from England (James I authorized each bishop to have a special collection), plus income from a 10,000 acre land grant on the north side of the James River.

George Thorpe, who had cared for one of the Native American's that accompanied Pocahontas on her 1616 trip to England, led the effort to build the college at Henricus. The land grant was located upstream from the Berkeley Hundred plantation (today's Berkeley Plantation) that Thorpe led, and the college was to be constructed on a Peninsula jutting into the James River between the mouth of the Appomattox River and the Fall Line.

In the uprising of 1622, Thorpe was killed, Henricus was destroyed, and plans for peaceful co-existence between the colonists and the Native Americans were replaced by reprisals and expulsion of the Native Americans from areas settled by the English. It took over 70 years before Virginians created another college.1

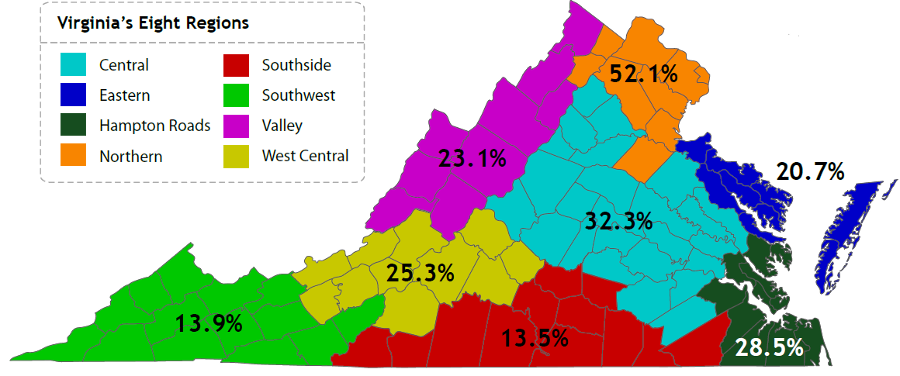

Henricus Historical Park is located near the site of the Colledge of Henricus, whose actual location probably was destroyed by gravel mining

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

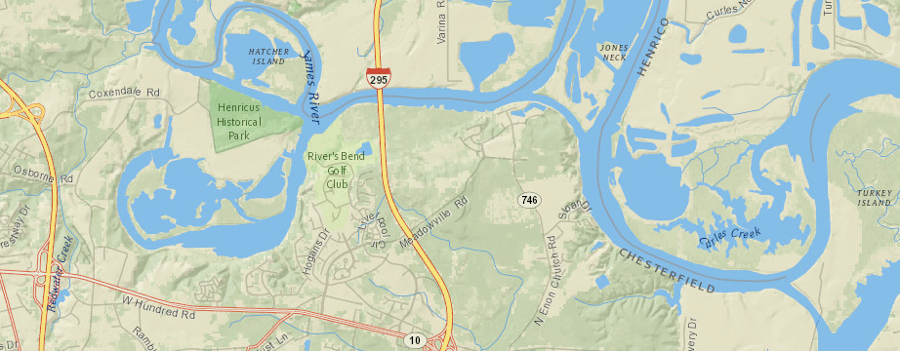

The next publicly-funded school in Virginia was William and Mary, the second-oldest (surviving) college in North America. The General Assembly authorized a school in 1661, but it was never funded. In 1690 the colonial legislature made another push, and King Willian and Queen Mary approved a charter in 1693. The sovereigns authorized a 20,000 acre land grant and dedicated certain tax revenues to fund the school, and the colonial General Assembly also directed revenues for support of the school at Middle Plantation (now known as Williamsburg).2

The College Building housed the General Assembly when it first met in Williamsburg in 1700, and served in that role until the first Capitol was completed four years later. (The College Building burned in 1705, and the Sir Christopher Wren Building occupies the site today.) By the start of the 1700's, the security threat from the Native Americans in Tidewater had disappeared. The new college included an "indian school," and in 1723 the Brafferton Building was constructed to provide a place "for the maintaining and educating such and so many of the ingenious scholars, natives of this colony, as they shall think fit."3

a statue of Lord Botetourt was in front of the Wren Building of William and Mary College

Source: "The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Directory, Containing an Illustrated History and Description of the Road," William and Mary College - Williamsburg (p.86)

During the colonial era, a few wealthy individuals such as Benjamin Symms and Thomas Eaton endowed about 10 local schools that offered free education.4

More commonly, parents in a community partnered together to establish "old field schools." These were elementary schools created, often in abandoned old agricultural fields, where parents would voluntarily pay tuition for a teacher to educate their children in the basics of reading, writing, and math. Further education, including reading the classics and learning Greek and Latin, was provided at "academies" supported by wealthy parents.

Washington and Lee University evolved from such an academy. Augusta Academy was founded in 1749, then moved to Lexington during the American Revolution and renamed Liberty Hall Academy.

ruins of Liberty Hall Academy at Washington and Lee University

Wealthy families such as the Carters and Lees hired private tutors, and those without wealth depended upon home schooling or privately-supported old field schools. There was minimal support among the gentry for funding public education:5

George Washington never received a formal education. His father died when he was 11 years old and family finances could not afford to send the younger children to a school. Washington taught himself, and benefitted from neighbors such as the Fairfax family to learn proper behavior, the rules of civility - and even the skill of surveying.

Philip Vickers Fithian, journal and letters, 1767-1774

(Journal in Virginia 1773-1774, December 15, 1773 - page 60)

Source: Library of Congress, American Notes: Travels in America, 1750-1920

After the American Revolution, Thomas Jefferson proposed a bill "for the more general diffusion of learning," as part of his campaign to increase the opportunity for individuals who were not part of the "artificial aristocracy" of the those who had excessive opportunity for obtaining power through family connections or wealth. Jefferson had received formal education, including studies at William and Mary. Rather than advocate universal K-12 education, he sought to identify the best students at several levels and provide additional education to just the "most promising subjects." As Jefferson described his proposal in 1786, he proposed:6

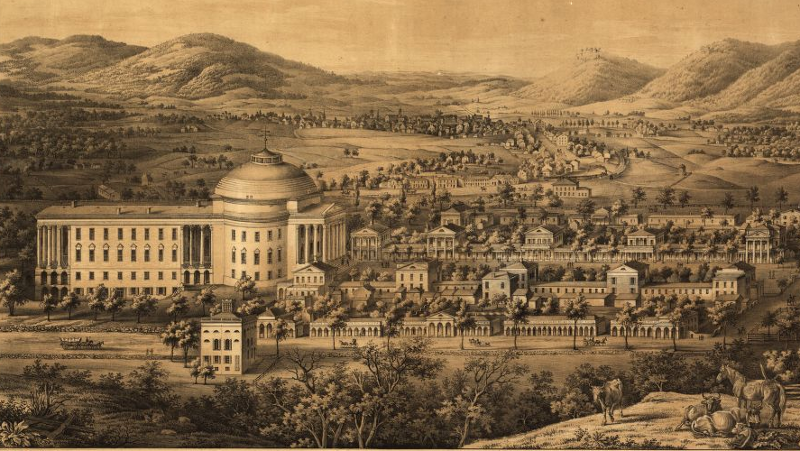

The General Assembly rejected Jefferson's proposal, but did charter the University of Virginia in 1819. That school was located just a few miles away from Jefferson's home at Monticello, on land once owned by James Monrow. It was far from the Tidewater region, and thuse offered students a chance to experience a culture based on small farms rather than the plantation aristocracy near Williamsburg.

Thomas Jefferson expected the University of Virginia to educate the best students, the "diamonds" extracted from the "dunghill" of average students

Source: Library of Congress, University of Virginia Rotunda, Charlottesville, Virginia

A state Literary Fund was established in 1810 to support education of the indigent poor. However, it was not until the Confederacy was defeated in 1865 that Virginia was transformed by both the abolition of slavery and the creation of a free public school system supported by state/local taxes. The 1870 state constitution required local jurisdictions to operate free public schools, and Virginia voters ratified the "Underwood" Constitution in order to be readmitted into the Union.

Even prior to adoption of that new constitution, a system of free public schools in Virginia was created by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands after the Civil War. The Freedmen's Bureau funded construction of school buildings for the formerly enslaved to get fundamental education. Many of the educators in those buildings were local African-Americans who, despite state laws restricting education to whites, learned how to read, write, and do basic math. Northern aid societies also were key, funding supplies and sending teachers.7

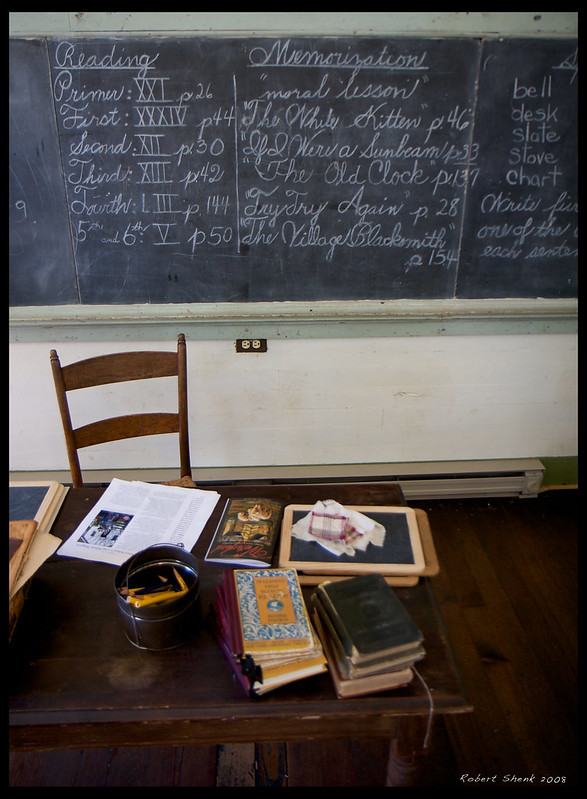

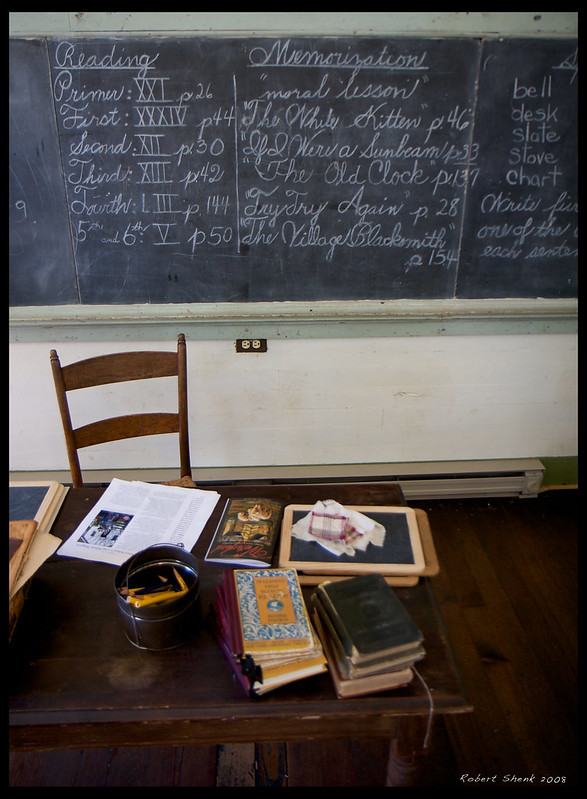

one-room school house in Waterford (Loudoun County)

Source: Rob Shenk, Old School

The new public education system implemented after adoption of the 1870 state constitution was very different from modern schools:8

The 1870 state constitution required creation of a free public school system for all races. However, the new requirement did not include a provision that the races were to be taught together in the same buildings. Racially-segregated schools were established and remained separate (though not necessarily "equal") until court mandates to desegregate. The Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 and a 1955 decision required that desegregation be implemented "with all deliberate speed."

Virginia's political leaders adopted a program of Massive Resistance to desegregation, hoping that delay would lead to revisions in the Federal mandate. The Massive Resistance strategy included pupil assignment practices that blocked efforts of black families to have their children attend white-only schools that were closer to home and offered a better education.

In 1958, state law forced some schools to close for a semester rather than to admit a black student. Prince Edward County officials shut down the county's entire public school system for four years, and did not reopen until 1964 in response to a court order. Maintaining racial discrimination and "de jure" segregation was a higher priority to Virginia's white leaders that offering a free public education, even if white children would also be impacted.

Nearly all public schools were finally desegregated in 1967. Discrimination continued by gender in state colleges until a court order forced an end to that practice in 1970. The last holdout was the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). It refused to allow women to enter and join the "rat line" until 1997, 158 years after the school was founded.9

one-room school house in Waterford (Loudoun County)

Source: Rob Shenk, Old School

in 1990, educational attainment in Northern Virginia was starkly higher than in other regions

Source: University of Virginia, Weldon Cooper Center, Population 25 Years or Older: Bachelor's Degree or More (1990 Census)

in Virginia's most-rural areas, less than 80% of the population over 25 has completed high school

Source: Census Bureau, How Much Schooling Have People Completed? (October 16, 2019)

the Brafferton at William and Mary was built in 1723 to educate and acculturate Native Americans

before World War II, female teachers in charge of one-room schools were common in Virginia

Source: National Park Service, NPS History Collection - National Capital Region

providing Safe Routes to School is not a new issue

Source: National Archives, Traffic Officer (May 1953) and School Children Crossing Roadway (October 1949)

University of Virginia in 1856, when Rotunda had been expanded to include an annex on side opposite from The Lawn

Source: Library of Congress, View of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville & Monticello, taken from Lewis Mountain

buildings at Longwood University are made primarily from brick

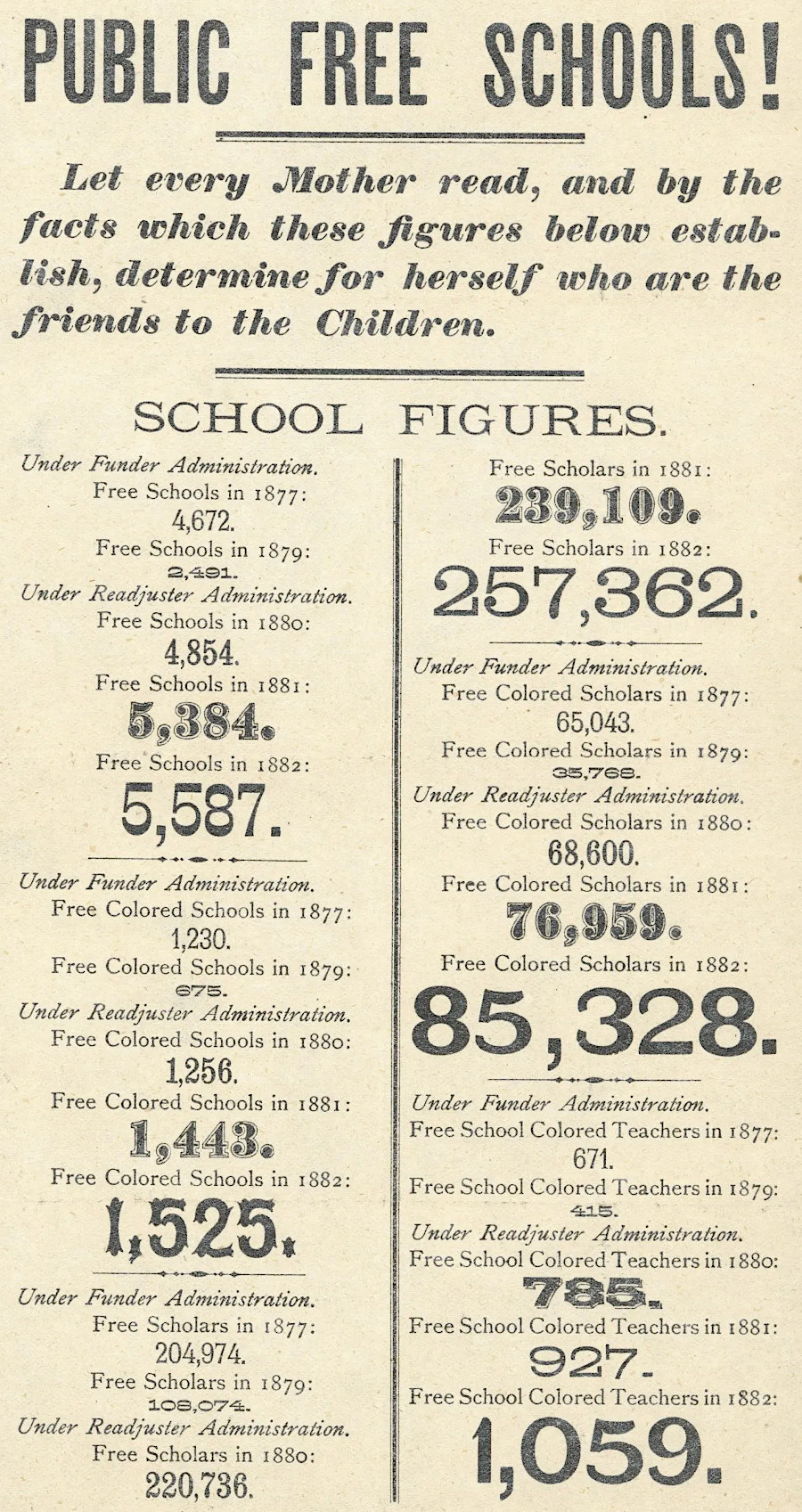

the Readjuster Party prioritized state funding for public schools, rather than paying off the state debt, after the Civil War

Source: UnCommonwealth blog, Library of Virginia, Justice For Ourselves: Black Virginians Claim Their Freedom After Slavery