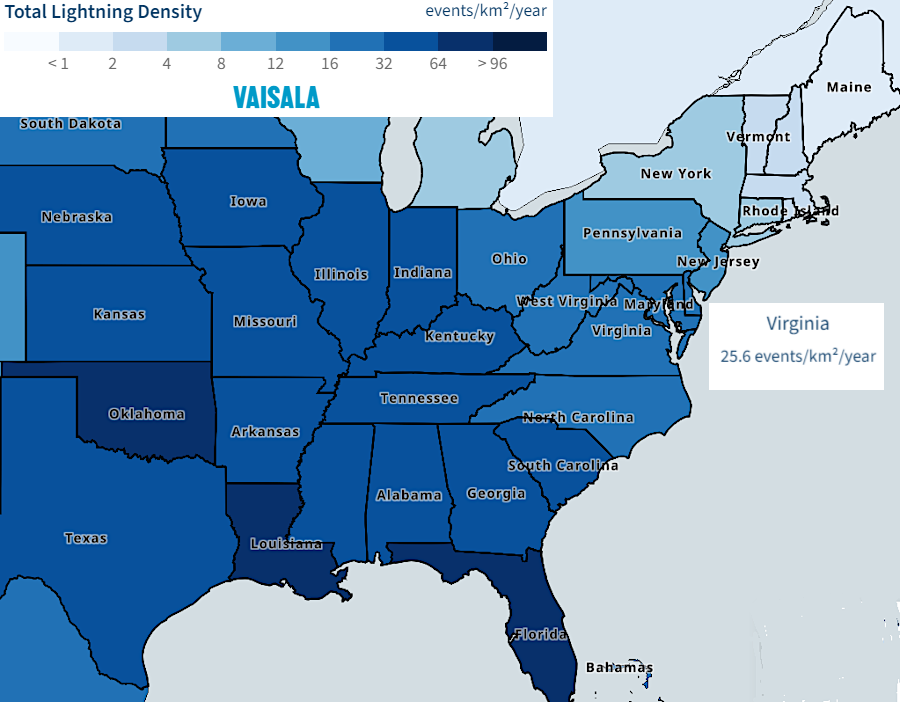

Virginia's lightning strikes are concentrated east of the Blue Ridge, in the southern Piedmont and Coastal Plain

Source: National Weather Service, Virginia Thunderstorms and Lightning, 1989

Virginia's lightning strikes are concentrated east of the Blue Ridge, in the southern Piedmont and Coastal Plain

Source: National Weather Service, Virginia Thunderstorms and Lightning, 1989

Nationwide, there are 37 million cloud-to-ground lightning strokes a year, and 56 million strokes counting cloud-to-cloud lightning as well. Previous estimates were 20-25 million cloud-to-ground lightning strokes a year, and the number is still being refined. Lightning "flashes" can include multiple strokes that strike the ground in different locations within 6 miles over a one-second period.1

Lightning is a giant spark associated with water in the atmosphere:2

Most lightning in Virginia is associated with the 35-45 thunderstorms that occur within the state each summer. Lightning and thunder are common in July and August, but "thundersnows" are possible in January as well.

The biggest storms, hurricanes, rarely generate lightning:2

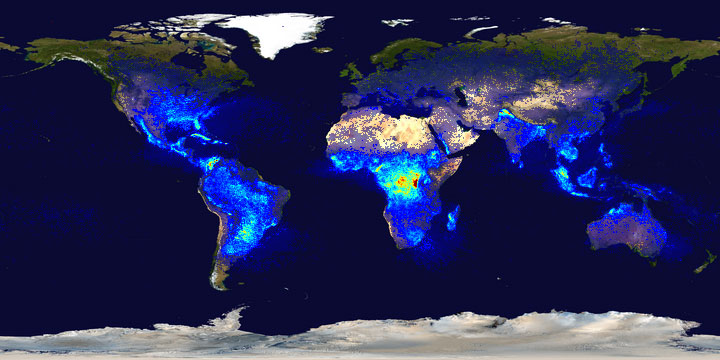

lightning is most common in central Africa and northern Venezuela, and least common at the North/South poles

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NASA Researchers Explore Lightning's NOx-ious Impact on Pollution, Climate

Lightning is an electric channel that rebalances the negative charges in the atmosphere with positive charges from the ground. As cumulonimbus clouds form, positive electrical charges accumulate on the small particles or ice and water that are lifted up into the tops of clouds. Negative charges accumulate on the larger particles at the bottom of the clouds.

The electrical differences can be equalized by a cloud-to-cloud lightning bolt. When seen from so far away that no noise is heard from a cloud-to-cloud strike, the event is often described as "heat lightning." There is a heat differential that shapes the air mass and the form of moisture in clouds, but heat is irrelevant to the actual lightning strike.

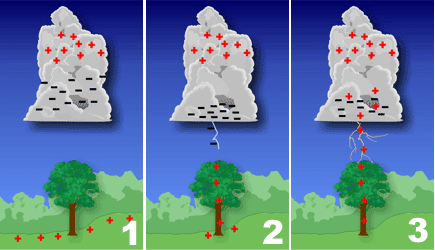

Lightning strikes between clouds and the ground start with a negatively-charged "leader" stretching from the bottom of the negatively-charged cloud towards the ground. The negatively-charged leader stimulates a positively-charged "streamer" moving up from the ground.

When the two link 100-300 feet above the ground, negative ions start down the leader but are quickly overwhelmed by a surge of positively charged ions flowing up the streamer. The initial small "flash" from cloud-to-ground is followed immediately by a massive return flash from the ground to the sky. The two-step process can be documented by cameras and other technology, but few observers can notice the separate stages. The two stages together trigger the discharge of electrical energy known as a lightning strike, typically 3-4 miles long.

According to the National Weather Service, what we notice is the up-from-the-ground-and-into-the-cloud strike:4

sequence of a lightning strike: 1) a negatively-charged leader from the cloud stimulates 2) a positively-charged streamer to move up from the ground, and 3) the return flash from ground to sky creates the bright light that people see as a lightning bolt

Source: National Weather Service JetStream Max: The Lightning Process: Keeping in Step

The two-stage process involves electricity flowing down from the cloud and then up from the ground. However, the transient pulse is not alternating current equivalent to the flows in the modern electrical grid. Lighting strikes are a direct current phenomenon.

Lightning may strike twice in the same place because the lightning channel can be reused. The excessive negative charge within a cloud may not be completely discharged by one strike. If small, short-lived "needles" of negative charges still remain, a new strike may follow the path of the previous one. The record to date is 26 return flashes at one spot.

The record length of a lightning strike is 515 miles. That mega-flash lasted over seven seconds. It was documented using data from four satellites and ground-based sensors in the Total Lightning Network of Earth Works.5

lightning starts when electrical charges in a cloud separate into a top with a positive charge and a bottom with a negative charge, and then a negatively-charged "leader" from the cloud meets a positively-charged "streamer" from the ground

Source: National Weather Service, How Lightning is Created

The energy discharged during a lightning strike can heat air particles to over 50,000℉. That creates a supersonic expansion of the air for a channel within 30 feet of the path of a lightning strike. The fast-colliding air particles heated by the flow of electricity create the sound of thunder, not the rush of those particles back into a vacuum created by the strike.

High-frequency sound waves are absorbed and scattered, so thunder has a low pitch. The "rumble" is created by the generation of sound at different elevations as the flash heats the atmosphere, causing people up to 10 miles away to hear different frequencies/volumes of sound.

Because the upward flash of a streamer is most intense, thunder starts at ground level. The light of the flash travels through the atmosphere five times faster than the sound of the thunder, at 186,291 miles per second for light vs. 1,088 feet per second for sound. If an observer can count "one Mississippi, two Mississippi, three Mississippi, four Mississippi, five Mississippi" before hearing the rumble of thunder, the lightning strike was about one mile away.6

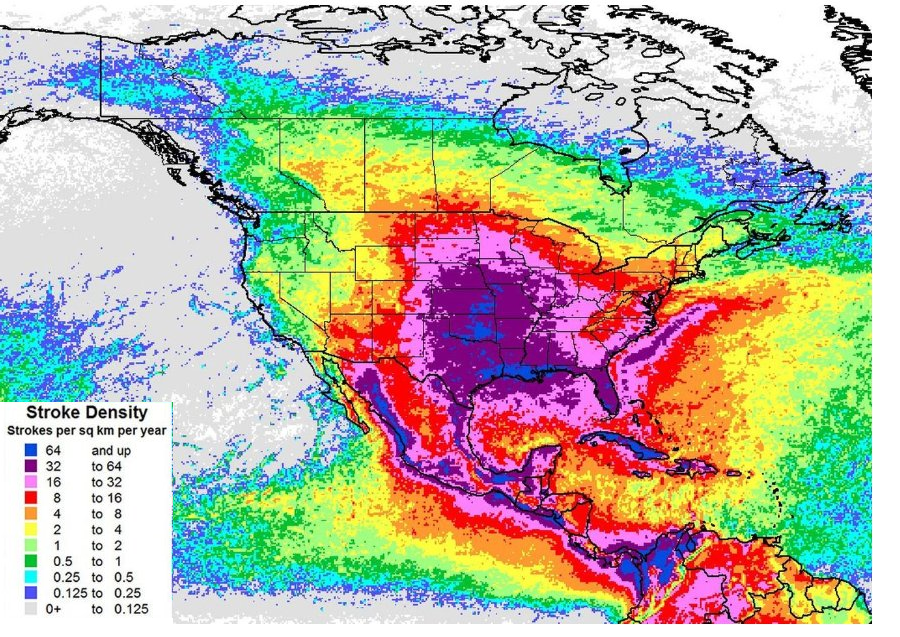

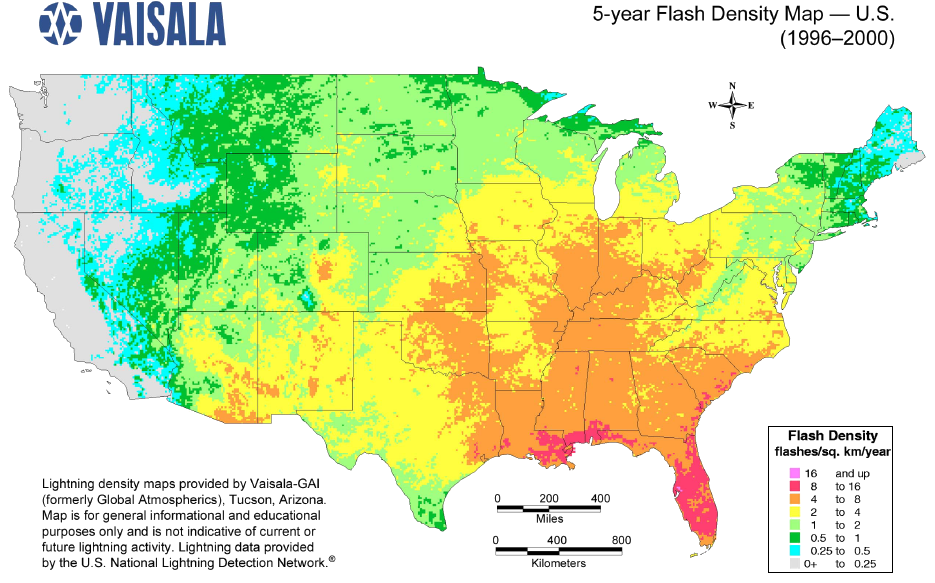

Worldwide, there are 1.2 billion lightning flashes annually. On average, Virginia gets 300,000 cloud-to-ground lightning flashes annually. In the United States, lightning is most common in Florida and along the Gulf of Mexico. As storms move up the East Coast towards Maine, they lose intensity and the number of lightning strikes drops.7

lightning strikes reflect the pattern of summer thunderstorms triggered by Gulf of Mexico moisture

Source: Vaisala, Lightning

lightning strike density reflects the changes as storms moving north from Florida lose intensity

Source: Vaisala, Global Lightning Density Map

About 5% of lightning strikes are "positive," connecting the tops of the clouds with the ground. Such strikes can be the "bolt out of the blue," hitting the ground far from any obvious storm cloud. The occasional positive lightning strike is usually more powerful than the normal lightning bolt, and may be the cause of many electrical blackouts and forest fires.8

In 2011, lightning triggered the Lateral West Fire at Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. The fire burned over 6,000 acres. The standard approach for fighting fire at the refuge is to flood the swamp, pumping water into the ditches and drowning the fire. However, even the massive 12-inch rainfall from Hurricane Irene a month later could not penetrate the peat soil and completely extinguish the Lateral West Fire.

lightning strikes triggered the Lateral West Fire at Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, which burned hot enough to create at least one fire tornado

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, A tool to hunt fires in the Great Dismal Swamp?

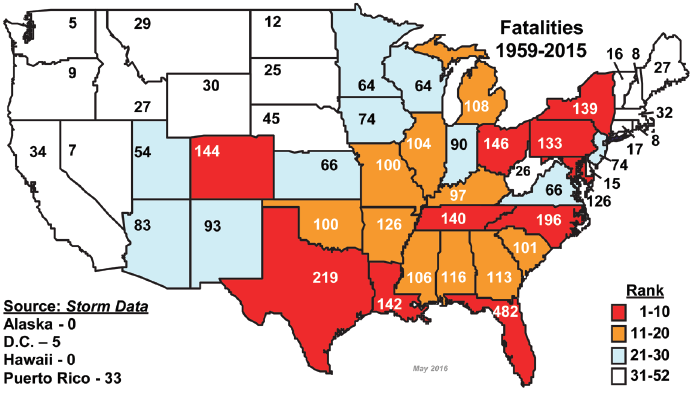

Lightning strikes people as well as power lines, trees and swamps. On average, 1-2 people in Virginia are killed by lightning each year; since 1959, over 60 people have been killed by lightning in Virginia. Lightning struck a signal tower in Alexandria on June 6, 1950, causing a train crash that injured 11 people.

Most lightning deaths in the United States are men outdoors: "males between the ages of 20 and 40 years old who were caught outdoors on ballfields, near open water, or under trees."9

In 1968, while Governor Godwin was at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, his daughter was killed by a lightning strike at Camp Pendleton (the "Camp David" for Virginia's top officials, in the southern part of the City of Virginia Beach). The sky was clear as the 14-year old stepped out of the surf; the only clouds were part of a thunderstorm offshore. The governor's daughter was the victim of a positive lightning strike, from the positively-charged top of a cloud.10

One ranger at Shenandoah National Park, Roy Sullivan, holds an apparent world record for surviving seven separate lightning strikes between 1942 and 1977. He finally died in 1983, not from direct effects of a lightning strike but by suicide. A record of his lightning strikes notes:11

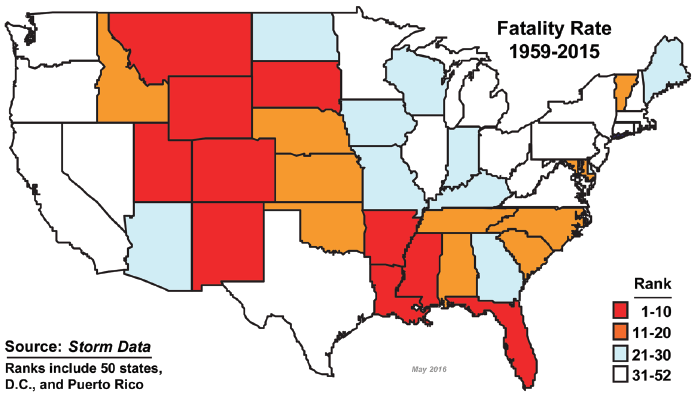

Virginia is not in the top 10 states for lightning fatalities

Source: National Weather Service, Lightning Fatalities by State, 1959-2015

when population is considered, western states have higher fatality rates - and Virginia drops even lower in the rankings for lightning fatalities

Source: National Weather Service, Lightning Fatalities Weighted by Population by State, 1959-2015

lightning patterns in the United States

Source: National Weather Service, Lightning Safety