water droplets evaporating on the roof of a cave typically create hollow soda straws first

Source: National Park Service, Speleothems (photo by Dale Pate)

water droplets evaporating on the roof of a cave typically create hollow soda straws first

Source: National Park Service, Speleothems (photo by Dale Pate)

The US Geological Survey (USGS) classifies different types of caves. Solution caves are formed by slowly moving ground water dissolving carbonate or sulfate bedrock, All natural caves in Virginia today have been formed by solution. Lava caves are created by fast-moving lava flows. Sea caves are carved into bedrock by wave action. Glacier caves are excavated by meltwater moving through ice.

Eolian caves are created by winds carrying silt/sand particles that sandblast a hole. It is common for wind and sand to create an arch, but there are caves within sandstone formations. Sand Cave in Cumberland Gap National Park is accessed via the Ewing Trail. The parking and trailhead are in Virginia, but the cave is across the state line in Kentucky.

Sand Cave, just across the border in Kentucky

Source: Frank Kehren, Sand Cave

A simple definition for a cave is:1

That definition excludes human-excavated caverns, including some made to store natural gas. There are many networks of underground mine shafts and tunnels created to remove ore and coal, and numerous tunnels excavated for railroads and highways. The skills required for spelunkers to explore caves are useful skills for workers who maintain non-natural features, but all underground holes are not caves.

Source: AtlasPro, How Do Caves Form?

Cave formation (speleogenesis) is the process by which a cave is created naturally. Within a cave, the "formations" are the unusually-shaped rocks such as stalactites and helictites.

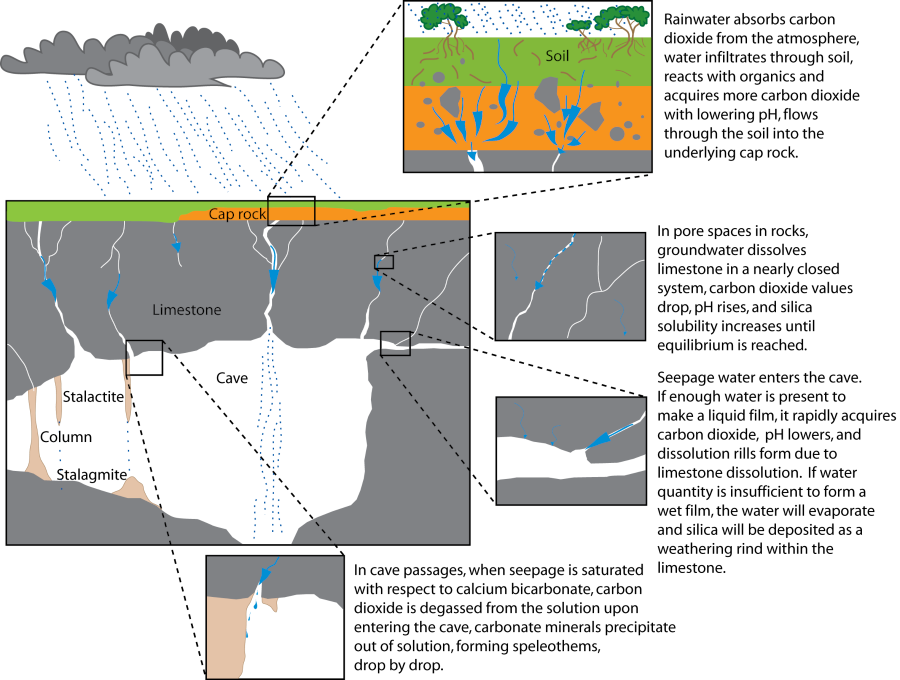

All natural caves in Virginia are in calcium-rich limestone and dolomite rock formations. The fundamental chemical and physical process is that slightly-acidic water, a mild carbonic acid created by hydrogen-rich gases released by bacteria in the soil and bedrock, dissolves calcium-rich bedrock near the top edge of the water table.

Slowly flowing groundwater in porous rock formations carries away the dissolved calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and carbonate (CO3) ions in solution. Some iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), and other ions will also dissolve. Left behind is a cavity.

The underground hole is supported by adjacent rock that has not dissolved. That prevents the overlying rock from collapsing, filling the cave and creating a depression on the surface. As rock dissolved underground, sinkholes may form as the surface is depressed.

sinkholes are depressions in the surface created when limestone/dolomite dissolves underground, as shown in this LIDAR image of land next to US 460 in Giles County

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, LIDAR

There are no volcanic lava tubes forming caves in Virginia, in contrast to California, Hawaii, the Canary Islands, Australia and Iceland. Lava tubes may have formed in the past, such as when Rodinia split up and what is now the Blue Ridge was coated with the Catoctin Formation 570-550 million years ago.

There are lava caves on the moon. What has been described as an "internal volcanic plumbing system" could provide shelter for astronauts to avoid dangerously high radiation levels. Within Virginia, any lava tubes which may have formed in the past have been destroyed by pressure from deposition by new rock layers on top, or by tectonic squeezing from the sides.

Fractured sandstone formations erode away. Water enters cracks, freezes and expands, and widens the cracks. Gravity, rainfall, and winds carry away sand particles from the edges of a formation, sometimes leaving behind arches that eventually fall as well.

Winds and water once carved eolian caves and arches in what is now Virginia, but they have since disappeared. There are still sandstone rocks with deep and narrow slots between them at The Channels, and places where rock slabs have fallen and created cubbyholes in the talus, but those are not "caves."

There are no caves in the sandy, loosely-consolidated formations of the Coastal Plain. Any holes that may form underground in those soft sediments are quickly filled by sand flowing by gravity to fill the space. The sand particles adjacent to a hole are not "competent" enough, not rigidly attached to each other tightly enough, to maintain a hole.

There are sea caves across the world, formed by waves excavating rock formations at sea level. Incoming waves compress air against the bedrock. The compressed air can push against the rock hard enough, along with the pressure from the water, to carve out holes.

There are "thunder holes" in some places such as Puerto Rico where a crack at the back of a cave can be a relief valve; air and water compressed into the cave can spout up through a crack. At Bar Harbor, Maine:2

unlike Puerto Rico, Virginia has no rocky shoreline in which a sea cave might form

Source: Wikipedia, Los Morrillos (Cabo Rojo)

tourists at Acadia National Park assemble t Thunder Hole 1-2 hours before high tide

In Virginia, however, there are no sea caves or thunder holes. The state's Atlantic Ocean shoreline is composed of soft sediments. As sand is washed around, other sand particles fill any gaps.

Caves rarely form in the metamorphic rock formations in the Piedmont, or in the igneous and metamorphic rocks of the Blue Ridge, or in the metamorphic and quartz-rich sedimentary rocks that form ridges in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, or in the quartz-rich sedimentary formations of the Appalachian Plateau. Bedrock in those physiographic provinces do not dissolve easily like limestone or dolomite, with ions going into solution and leaving a cavity in that space.

Joints and faults in metamorphic bedrock can create zones of weakness where smaller particles, created by pressure, wash away and leave behind a crack. The Channels Natural Area Preserve on Clinch Mountain formed after cracks in the sandstone eroded faster than the blocks of stone between the fractures. The channels are 10' deep in places, but open at the top so they are not caves.

In dolomite and limestone formations, the minerals go into solution and leave behind cavities which grow into caves. In metamorphic and igneous formations, mineral crystals alter their shape as erosion removes overlying layers because temperature and pressure are reduced as rock formations come near the surface. Felspar, quartz, biotite, hornblende, and other minerals do not dissolve readily, so the minerals change as the bedrock nears the surface but do not dissolve into groundwater easily.

In addition to changes in temperature and pressure, groundwater and organic material from roots and animals also causes atoms in minerals to realign. As bedrock slowly morphs into soil, its cohesion is reduced and its porosity and permeability increases with tiny pores between particles. In Virginia's Piedmont, the decomposing bedrock ("saprolite") might be 100' thick.

As feldspar and other minerals slowly transform, they form clay particles which occupy the space of the previous crystals. Tiny cavities in saprolite do not coalesce and join to form caves.

When large rocks fall in a jumbled heap, the gaps between them may resemble a cave. One such "cave" in the Piedmont is Devil's Den in Carroll County near Fancy Gap. According to local lore, Floyd and Sidna Allen hid there briefly after the 1912 shootout in the county courthouse in Hillsville.

The cave is no longer open for public entry, but bats scout it for a home. As described by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources:3

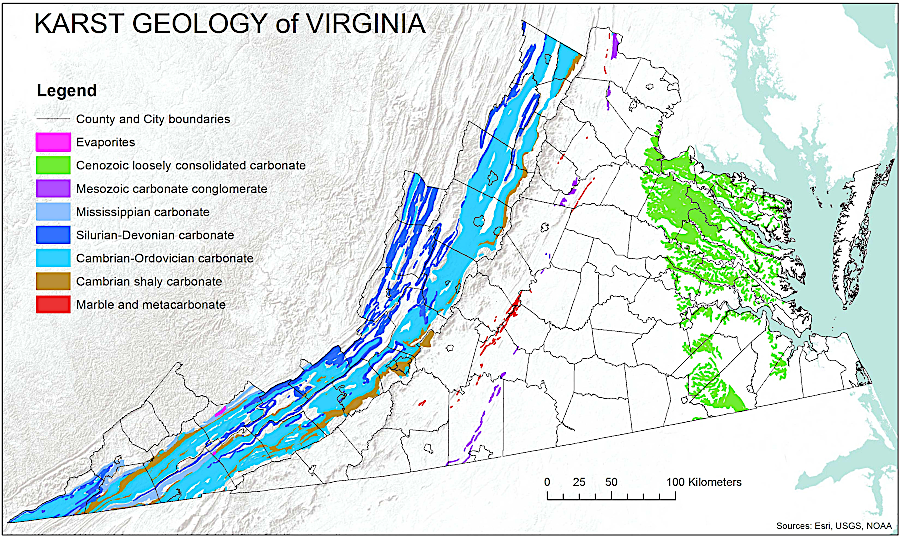

Virginia's solution caves have formed in multiple ways within seafloor sediments that were deposited 550-250 million years ago at the bottom of the Iapetus Ocean, and are now exposed primarily in the Valley and Ridge province west of the Blue Ridge. A few Virginia caves are located in limestone/dolomite formations east of the Blue Ridge.

calcium-rich sediments are located east of the Fall Line, but nearly all caves are west of the Blue Ridge in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Virginia Natural Heritage Karst Program

Within the calcium-rich remnants of the Iapetus Ocean that are now at the surface in Virginia, different sedimentary formations are defined by geologists based on the conditions and time when the rock was deposited. The chemistry of sediments within those formations, and the pressures that squeezed them, determine if the bedrock is susceptible to being dissolved by groundwater. When groundwater can dissolve cavities within one formation, and especially if it is surrounded by harder bedrock that will not collapse, large holes in the ground can develop.

"Phreatic" caves form near the water table where groundwater saturates a layer of limestone/dolomite. Over time, slowly-moving groundwater dissolves portions of the bedrock and carries it away in solution. The cave which forms underground consists of water-filled passages. If a nearby stream erodes a deeper channel, groundwater will emerge at a lower level. The groundwater level can also drop if the climate changes, as occurred in the recent ice age.

As the water table drops, dissolved channels underground gradually become an air-filled cave. The "phreatic" (water-filled) channels become "vadose" (air-filled) channels. Connecting channels can be of varying widths, often with twists and turns which allowed water to move but today are too narrow for modern cavers to navigate.

If warm water from below had mixed with cool water near the water table, spaces shaped like domes can form. Cave roofs can collapse as cavities form. Changes in the level of the water table and earthquakes can trigger rockfalls. Rockfalls may fill up cavities beneath them, but can also open spaces in the old roof of a cave and create "breakdown rooms" with high ceilings.

If the hole underground can not be supported by the remaining rock, the roof will collapse. If the collapse is close enough to the surface, a sinkhole depression may form. Sinkholes may also develop when a small crack in the bedrock above a cave allows soil and water to flow slowly down into the cave, without any roof collapse. Sinkholes, a form of a doline or closed circular depression, are classic indicators of karst topography where caves are most likely to be found.

Underground pathways can be at different levels, reflecting how the water table changed at different times. Mammoth Cave in Kentucky has four "fossil levels" above the still-flowing river level, which is 300' deep below the surface.4

A "dry cave" no longer has surface water seeping through the soil and bedrock and reaching the top of the air-filled passage. In a "wet cave," groundwater will drip into the underground cavity. Droplets of groundwater will flow through the cave and emerge on the surface as a spring.

Once the humidity in an air-filled cave passage drops below 100%, some of the groundwater water will evaporate into the atmosphere of the cave.

speleothems form slowly, as droplets of water evaporate and leave behind a thin film of calcium-rich minerals

Source: National Park Service, Solution Caves

When a drop of water evaporates underground in a cave, it may leave behind a tiny deposit of the calcium that the drop had dissolved during its journey down from the earth's surface. The atoms in calcium carbonate can align themselves to form the minerals aragonite or calcite.

The calcite/aragonite in limestone and dolomite does not dissolve easily in pure water. Organic material in the soil can convert rainwater into a weak carbonic acid (H2CO3) that dissolves calcite/aragonite (calcium carbonate with the chemical formula of CaCo3) by converting it into the more-soluble calcium bicarbonate with the chemical formula of Ca(HCO3)2.

When a drop of water with dissolved calcium bicarbonate evaporates in a cave passage, the chemical process is reversed. CO2 is released from the drop as a gas, and the residue is calcium carbonate.5

Thin films of aragonite/calcite grow where droplets of water evaporate at the ceiling of a cave. Over time, a cave formation that resembles a soda straw gradually increases in length. A half-inch wide "soda straw" with a drop of water on the bottom is a very common cave formation. Such soda straws can grow over a foot long.

Once a piece of grit or a grain of calcium carbonate blocks the water's flow through the middle of a soda straw, the film of water will drip along the outside of the formation. Calcium deposits make the formation wider as well as longer. This process creates - over hundreds or thousands of years - the stalactites that hang from a cave ceiling.6

when hollow soda straws get clogged, water flows on the outside of the tube and a stalactite develops

Source: National Park Service, Speleothems (photo by Ronal C. Kerbo)

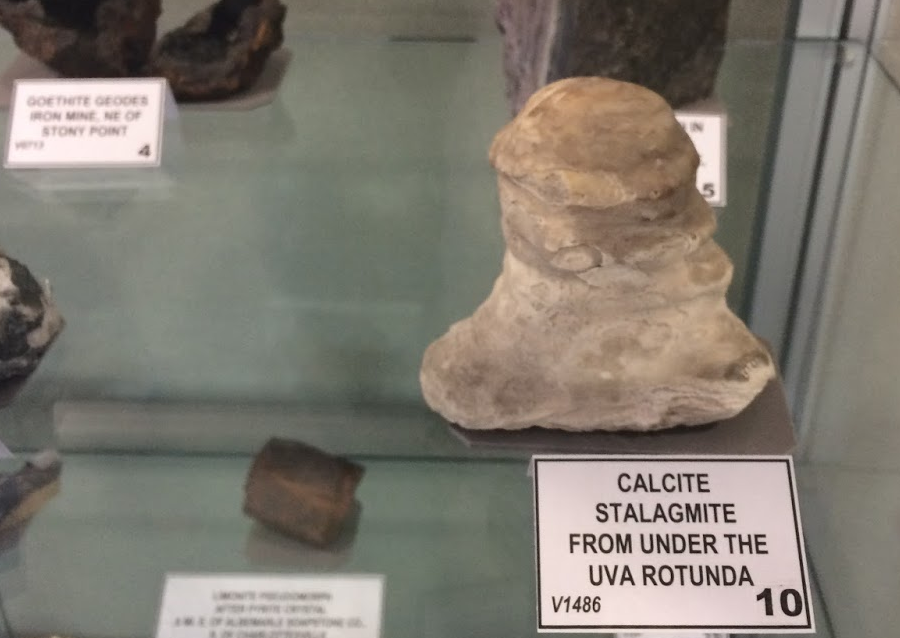

If drips of water fall to the cave floor before evaporating completely, they carry a portion of the dissolved calcium bicarbonate with them. When the water droplets then evaporate on the cave floor, the calcium is deposited on a growing stalagmite - the cave formations that grow upwards from the floor of the cave towards the ceiling. Stalagmites are often located just below a stalactite, and when the two finally grow together a column is formed.

A simple mathematical law determimes how stalagmites grow as calcium-enriched water droplets land on the floor of a cave. Cone-shaped stalagmites with a point at the top are created when drops fall relatively fast, hitting the same spot. Wider, flat-topped stalagmites in the form of a column are created when drops fall from a greater height and splatter, rather than consistently hit the same spot.

stalagmites grow upward from the bottom of a cave floor, when droplets evaporate there and leave a residue of calcite/aragonite

Source: National Park Service, Speleothems (photo by Dale Pate)

stalagmites form at construction sites when cement leaches from structures

Other cave formations include flowstone, cave coral, helictites, draperies, and a variety of other shapes that reflect the rate of evaporation, the chemical composition of the local rock, and even tiny wind currents in the cave.

evaporation from slowly-flowing water creates the speleothem called flowstone

Source: National Park Service, Speleothems (photo by Dale Pate)

helictites can develop if capillary action on evaporating water droplets exceeds the force of gravity

Source: National Park Service, Speleothems

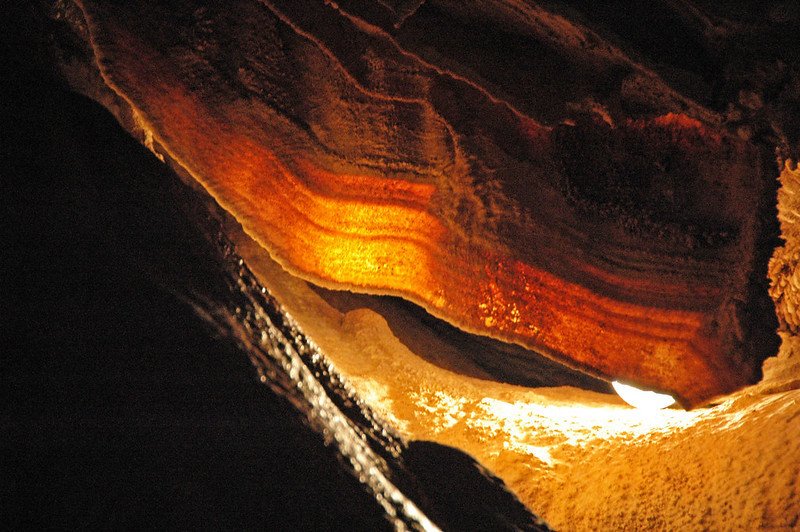

The colors in cave formations reflect the local minerals. Water flowing through iron minerals (hematite and limonite) will create reddish/yellow bands alternating with the white calcium carbonate, creating formations that resemble slabs of bacon with layers of fat and lean meat. Manganese will create black streaks on the cave walls and a black coating on the rocks in a flowing stream.

when groundwater carries dissolved iron into a cave, speleothems called draperies can end up with bands of different colors

Source: National Park Service, Drapery

dripstone with different percentages of iron and calcium minerals can create draperies that resemble slabs of bacon

Source: James St. John, Travertine drapery (cave bacon)

The rate at with formations grow varies. In natural caves, speleothems typically grow just a few millimeters per year. The fastest growth rate for limestone formation (gypsum formations grow faster) is probably 10 centimeters/1,000 years.

In some cases, growth can be rapid. Marble buildings less that 100 years old (such as the Lincoln Memorial) and buildings with cement between bricks may grow soda straws quicky. Water seeps through cement, which often retains pockets of calcium oxide (CaO) from the cement production process. The water gets impregnated with calcium hydroxide - Ca(OH)2.

It is far more soluble that calcium carbonate or calcium bicarbonate. The greater amount of dissolved calcium in calcium hydroxide can speed the growth of stalactites where water seeps out of a structure made with cement. The creation of stalactites is not restricted to underground caves.7

cave formations (speleothems) at Grand Caverns (Rockbridge County)

There are a few locations where calcium or dissolved in the water may be deposited outside a cave or spring as travertine. One of the most-visited such sites is Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park. At various hot springs and geysers, silica dissolved in the water may be deposited at the surface.

At Falling Springs near Covington, at Falls Ridge Preserve in Montgomery County, and at Natural Bridge in Rockbridge County, water emerges from springs while still loaded with dissolved limestone. The flowing water on the surface deposits travertine (a form of calcium carbonate) along the edge of the pools and on the streambed just below the springs, forming dams that create the shallow pools. Calcium-rich water can deposit a visible film of rock on leaves and twigs within just a few months.8

The formations are fragile, however. One careless step by a visitor can destroy decades of rock formation. In addition, cave visitors are warned "don't touch" because the oils on our fingers will block the continued growth of a cave formation. The water droplet with its thin film of calcite/aragonite will slide off the formation, before it can evaporate and deposit another addition to the "living rock." Wearing gloves while caving is one method of minimizing impact.

Some caves are exposed when erosion from the surface intersects the cave, removing the roof and exposing the cave formations to wind and rain. Once exposed to rainfall, it takes only a short time (a few decades) to erode away the obvious signs that there was once a cave at that location.

Travertine and speleothems are exposed in a small stream entering the Shenandoah River about a mile downstream of the Route 50 bridge. The old formations are just barely visible today along a streambank that was once a cave passage.

Natural Bridge is the last remnant of a cave roof

The tallest stalagmite in the world is the "Hand of Dog" in the Son Doong Cave in Vietnam, the largest cave in the world by volume. That stalagmite stretches over 250 feet high.

The stalagmite was named in 2009 when two surveyors were mapping the cave. One called out to the other that the massive speleothem resembled the Hand of God. The acoustics in the cave room were poor, however. The second surveyor heard "Hand of Dog," and that was the official name added to the map.9

view from the top of the Hand of Dog stalagmite, tallest in the world, in Vietnam's Son Doong Cave

Source: Google Arts and Culture, The Hand of Dog

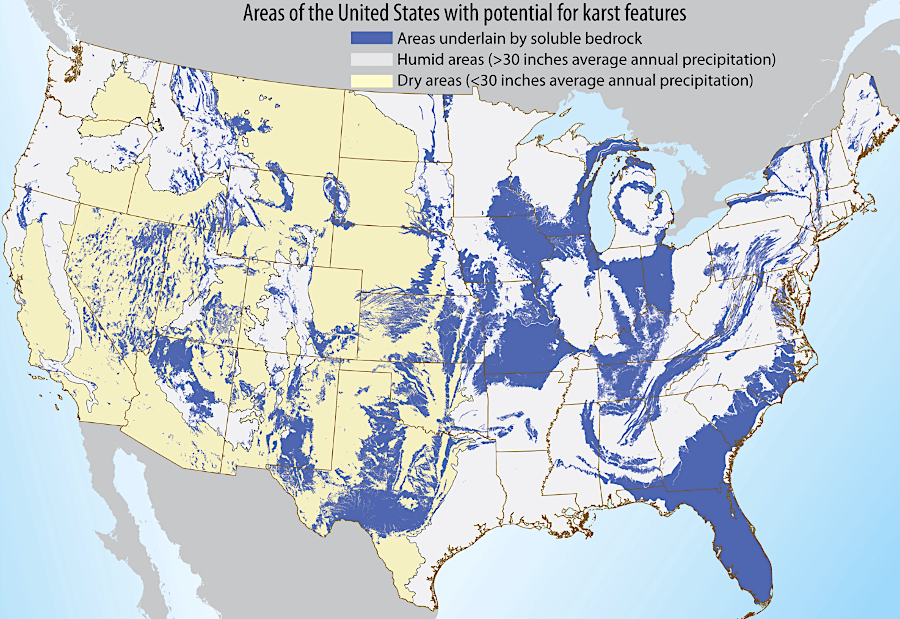

solution caves can form in many areas of the United States

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Areas of the United States With Potential for Karst Features

water saturated with calcium carbonate, evaporating in a cave, can create speleothems such as draperies

Source: National Park Service, Drapery