the location of Bermuda has been known by mariners since 1505

Source: Boston Public Library Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Orbis terrarum typus de integro multis in locis emendatus (by Petrus Plancius, 1594)

the location of Bermuda has been known by mariners since 1505

Source: Boston Public Library Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Orbis terrarum typus de integro multis in locis emendatus (by Petrus Plancius, 1594)

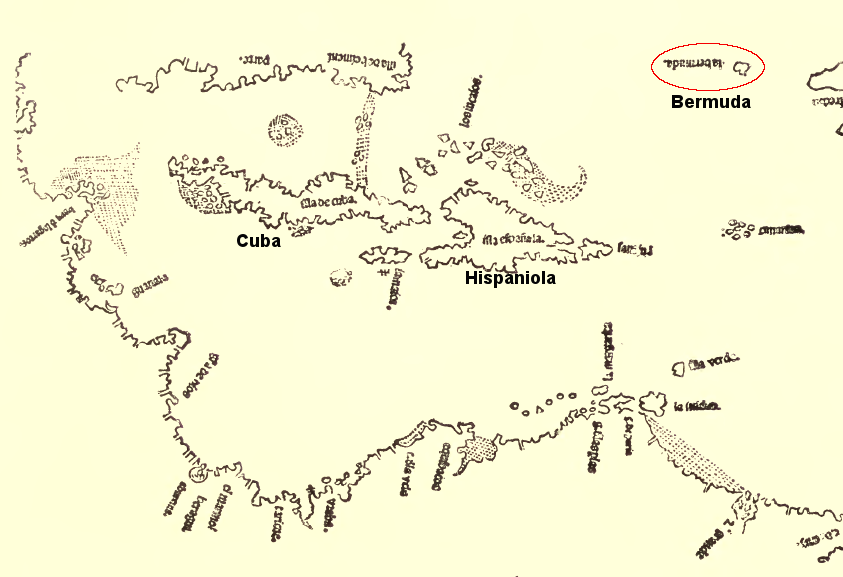

Spanish ship captain Juan de Bermudez discovered Bermuda in 1505, and the island was named for him. The Spanish treasure fleet used the island as a waypoint on their trips back home when ships were loaded with silver and goods from Manila.

Bermuda had water, wood, and a pleasant climate suitable for growing crops, but Spain had no reason to establish a colony there. There was no silver or gold, and no Native American who could provide labor or be converted to the Catholic faith. A Spanish captain, perhaps Juan de Bermudez himself, released hogs there - or perhaps enough swine survived a shipwreck to continue breeding. The pigs survived on the island, but Bermuda remained uninhabited for a century.

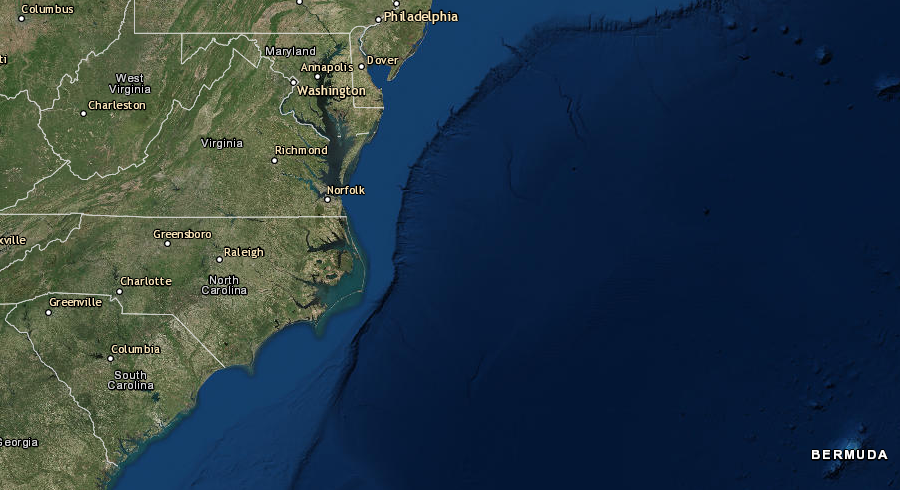

Bermuda is isolated in the Atlantic Ocean, 600 miles from the closest Carolina coastline

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

A storm near Bermuda interrupted the return of the treasure fleet in 1561. The ship with the son of the man in charge of the fleet, Pedro Menendez de Aviles, disappeared. The loss of a ship was not a uncommon event. If it had been blown back to the mainland, survivors could be living among the Native American communities. Hernando de Soto had found Juan Ortiz in south Florida in 1539, over ten years after he had been separated from the Penfilo de Narvaez expedition.

Pedro Menendez de Aviles negotiated with Spanish King Phillip II to obtain permission to search for his son, and to acquire control of land in what the Spanish described as Florida. Part of the bargain was that the search would include planting a new colony, mostly at the expense of Menendez de Aviles. He sailed to Florida in August, 1565. He arrived at the same time the French were trying to establish a colony at the mouth of the St. John's River with a fort (La Caroline) in what is now Jacksonville, Florida.

After killing nearly all the French, who were not only "trespassers" but also French Huguenot Protestants, Menendez de Aviles converted his military encampment on the Florida coast into the permanent settlement of St. Augustine. The next month, in October 1565, he sent a ship north to look for survivors of the 1561 storm.

That ship was also responsible for returning a Virginia-born Native American to his home. In 1561, the same year that the son of Menendez de Aviles disappeared near Bermuda, a young Native American known as Paquiquineo had been seized by Spanish explorers/slave-hunters from his home on the shores of the Bahia de Santa Maria (Chesapeake Bay).

After being taken to Spain and Mexico, Paquiquineo converted to Catholicism and took the name Don Luis. Spanish Philip II ordered that Paquiquineo/Don Luis be returned to Virginia, but the ship sent in 1565 by Menendez de Aviles failed to find the Chesapeake Bay. Paquiquineo/Don Luis ended up back in Spain again and did not get home until 1570, when he accompanied Father Juan Baptista de Segura on his Jesuit mission to Virginia.1

Spanish map showing the location of Bermuda in 1544

Source: Library of Congress, Portolan atlas of 9 charts and a world map, etc. Dedicated to Hieronymus Ruffault, Abbot of St. Vaast (c.1544)

The loss of a treasure fleet ship near Bermuda in 1561 is one link in the chain of events that led to the 1565 founding of St. Augustine, the oldest continuously-occupied city in North America founded by European colonists, and the 1570 attempt by the Spanish to start a colony on the Chesapeake Bay.

The first Englishman known to have been shipwrecked on Bermuda was Henry May. In 1593, he was aboard a French vessel whose pilots miscalculated their position and crashed into reefs of the northern edge of the island. The survivors used remains of their wrecked ship and local trees to build a new vessel, made watertight by mixing local lime with the oil of tortoises.

They loaded 13 live tortoises onto their ship before sailing to Newfoundland to catch a ride home with one of the fishing fleet there, later reporting that the feral pigs were a poor source of food:2

the shipwreck depicted on the Coat of Arms for Bermuda may reflect the first English occupation of the island by Henry May in 1593

Source: Wikipedia, Bermuda

The next time Bermuda played a role in European colonization was in 1609, and that event was also triggered by a storm. That time, the English rather than the Spanish were involved. The precipitating event was the grant by English King James I of a Second Charter to the Virginia Company on May 23, 1609.

That charter granted the investors all the land within 200 miles north and south of Point Comfort, extending inland "unto the lande, throughoute, from sea to sea, west and northwest" to the edge of the continent. The Second Charter did not expand Virginia's boundaries out into the Atlantic Ocean. It essentially repeated the language in the 1606 First Charter, and in contrast to the vague land boundaries defined a clear limit to authority in the ocean as:3

Since Bermuda was 600 miles away from North America, the islands of concern to the Virginia Company in 1609 were those along the Eastern Shore and Hatteras, "within one hundred miles" of the coastline. The English, like the Spanish, knew of Bermuda (John Dee had placed it on a map produced for Queen Elizabeth in 1580), but the isolated, uninhabited island with no mineral wealth was not a strong draw for either nation.

the location of Bermuda was no secret to the English sailors, but the English - like the Spanish - had little interest in the isolated island in the late 1500's

Source: Richard Hakluyt, Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation, Map of America (by John Dee, 1580)

The Second Charter helped revitalize interest in the Virginia Company. Under the First Charter issued in 1606 the Plymouth investors had failed with their settlement on the Kennebec River in Maine and Jamestown was struggling to survive, but the London investors expanded their commitment and recruited new investors. With the new funding, the company sent a fleet of nine ships, the Third Supply in 1609. It carried livestock, supplies and 500-600 colonists (including 100 women) to Jamestown.

As the name "Third Supply" indicates, the Virginia Company investors had sent two resupply expeditions previously to Jamestown. The First Supply arrived in January 1608. Christopher Newport brought the John and Francis first, and the Phoenix arrived after being blown off course. Together they brought 120 new settlers. Christopher Newport returned with the Mary Margaret in September 1608, bringing 60 new colonists in the Second Supply.

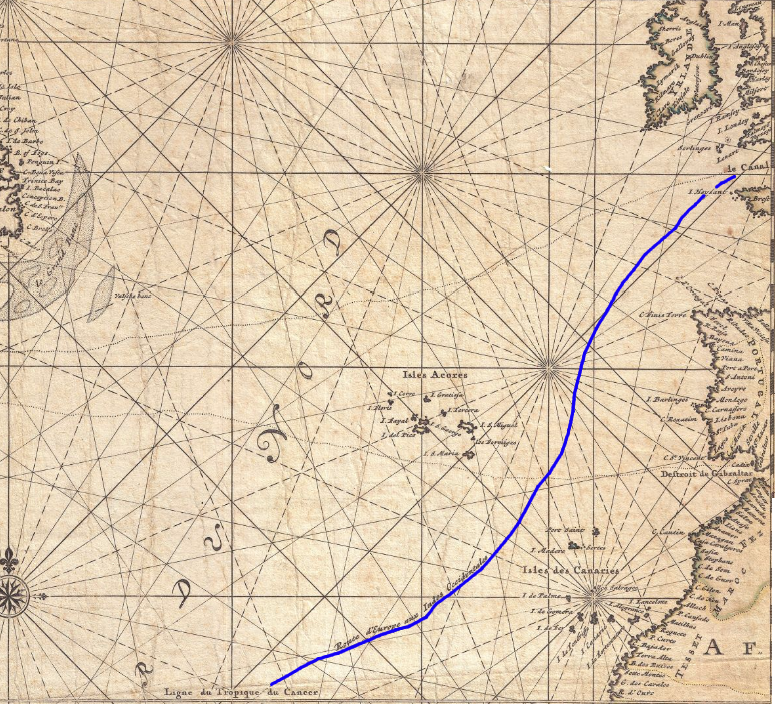

Those two resupply expeditions followed the "normal" pattern of sailing from Europe to the New World. Ships sailed south from England to the Canary Islands where water and supplies could be restocked if necessary. (Even though the Spanish controlled the islands, restocking vessels from other nations could still be profitable.) Ship captains then took advantage of the trade winds blowing from the northeast to go west, following the Tropic of Cancer across the Atlantic Ocean to the Caribbean.

After reaching the West Indies near Puerto Rico, the English sailed north, catching the Gulf Stream to go past the Bahamas to Virginia. That route took the English far south of the island of Bermuda.

the original trip to Jamestown in 1606-1607, and the First and Second resupply expeditions over the next 18 months, took the traditional route south to the Tropic of Cancer in order to catch the northeasterly tradewinds across the Atlantic Ocean

Source: Geographicus, Ocean Atlantique ou Mer du Nord (by Pierre Mortier, 1693)

The Second Charter dropped the king's authority to choose members of the company's governing council, and Sir Thomas Smythe began to manage it as Treasurer. When Smythe and Virginia Company officials chose to send the Third Supply, they also chose to reorganize the management in Virginia.

They decided to abolish the president/council structure that had for governing Jamestown since 1607. Instead, the Virginia Company sent with the Third Supply a "governor" to serve as the new leader.

The council in Jamestown, with a president elected by its members, had been conflict-ridden from its beginning in April 1607. When Captain Newport opened the box with secret company orders after the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery reached the coastline of Virginia, everyone learned that John Smith was supposed to be a member of the council.

At that moment, he was a prisoner; he had been held captive for much of the trip across the Atlantic Ocean. Smith was such a contentious member of the company that he was almost executed when the three-ship fleet was sailing through the Caribbean.

With diplomatic skill, Captain Newport had John Smith freed and added to the council before sailing home on June 22, 1607. In 1608, after multiple changes in authority at Jamestown, John Smith was elected to serve a one-year term as president of the council. His term was to end September 10, 1609. However, the Virginia Company back in London did not intend to wait for the completion of Smith's term before changing the structure of government in the colony.

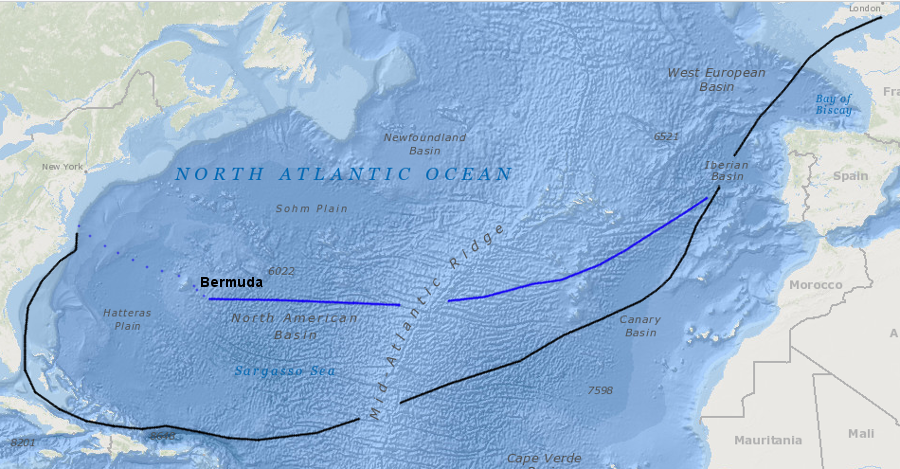

the Third Supply fleet sailed on a route (blue line) north of the traditional path (black line) that took ships from England to the West Indies first

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Sir Thomas Smythe sent Lieutenant-General Thomas Gates on the Third Supply to command the colony as the resident governor. Gates was to replace Smith and the council as soon as he arrived in July/August 1609. Gates was given sole and absolute powers to make decisions, though he was to appoint a council to advise him. His appointment eliminated the role of a council with a president holding two votes, which had been created in the original orders sealed in a box in 1606.

Technically, Thomas Gates was the "acting" governor. The Virginia Company had appointed Lord De La Warre as the new official governor, but sent Gates to Virginia in 1609 in the interim to serve a governor until De La Warre arrived. Gates expected to be in charge until Lord De La Warre had time to settle his affairs in England and sail across the ocean in 1610.

The Virginia Company decided to use a new route to Virginia. The traditional path was to sail south to the Spanish-controlled Canary Islands, and then turn westward. The winds at the latitude of the Tropic of Cancer (23.5° north of the Equator) would carry ships reliably to the West Indies.

In 1609, the English decided to try a more-direct route by turning west at a higher latitude. The pattern of winds and currents were more challenging, but taking a northern route would avoid the Spanish in the Caribbean. A more-direct route would also reduce the length of the journey, so the resupply ships would arrive at Jamestown with more food.

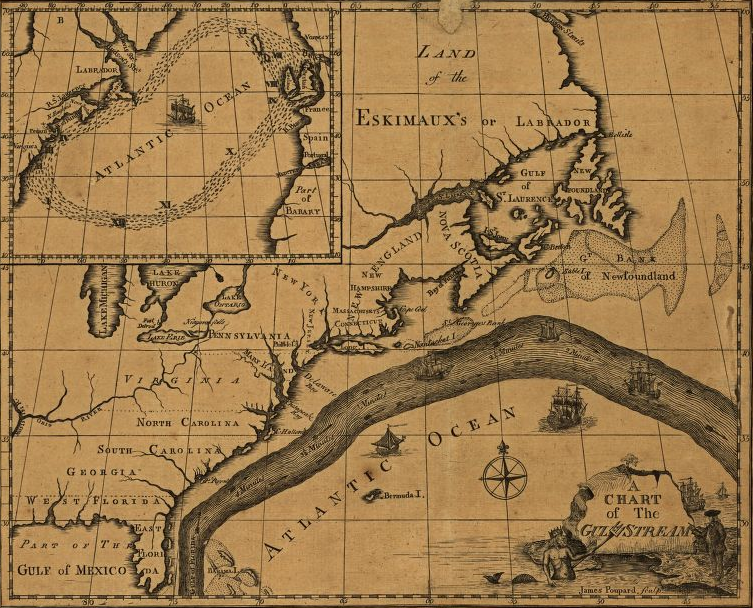

the Gulf Stream flows north of Bermuda

Source: Library of Congress, A chart of the Gulf Stream (by Benjamin Franklin and James Poupard, 1786)

Captain Samuel Argall was sent ahead in one ship to try the route. Once he arrived in Virginia, he was directed to fish to provide more protein for the colonists.

The major Third Supply included nine ships with 500 new colonists. Sir George Somers commanded the fleet, which followed Captain Argall's track when it left in June, 1609.

If Argall had found the route impracticable, he might return to alert the fleet and they could use the traditional route. In case the ships got separated in fog or by storms, the nine captains were instructed to meet at the Caribbean island of Barbuda just north of Antigua. Though the fleet sailed far north of the traditional track to the West Indies, the fallback for rendezvous was part of the old route.

the ships in the Third Supply fleet, including the Sea Venture, planned to rendezvous at Barbuda in case a storm separated them

Source: Utrech University Library, Archipelague du Mexique ou sont les Isles de Cuba, Espagnole, Jamaique &c. (by Pierre Mortier, 1727)

Sir George Somers was personally in command of the flagship Sea Venture, as well as admiral with overall command of the fleet. Sailing on the Sea Venture with Sir George Somers were Captain Christopher Newport (serving as vice-admiral) plus governor-to-be Thomas Gates.

Also on board the Sea Venture were Namontack and Matchumps, two of Powhatan's subjects that had sailed with Captain Newport to London in 1608 to be displayed by the Virginia Company. Powhatan and Captain Newport had exchanged young men to create interpreters. Namontack was sent to live with the English, while Thomas Savage was sent to live with the Native Americans and learn their language.

Namontack had visited London previously in 1608, going voluntarily to scout out the country. He was the first Virginia to travel voluntarily to Europe; Paquiquineo/Don Luis had been seized and carried way against his will 47 years earlier by the Spanish. Namontack's trip on the Sea Venture was his fourth crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.4

Among the 150 passengers and crew traveling on the Sea Venture was a man named John Rolfe and his pregnant new wife, plus a four-year old girl named Jane Pierce. She would become Rolfe's third wife. Between the death of his wife with him on the Sea Venture and his marriage to Jane Pierce, John Rolfe would marry Powhatan's daughter Pocahontas.

The nine ships stayed together as they crossed the Atlantic for seven weeks. The Sea Venture towed the smallest pinnace so it could keep up.

About a week away from the Chesapeake Bay, Somers acknowledged they were far north of the old West Indies track and Barbuda was no longer an appropriate rendezvous. He used his authority as admiral and altered instructions, issuing orders for the other eight captains to sail on separately to Virginia if necessary. Soon afterwards on July 24:5

When the storm hit, substantial leaks opened in the Sea Venture's hull and flooding threatened to sink the ship. Everyone on board, even Admiral Somers, helped to pump water for three days. As the storm finally passed, land was sighted. Somers steered into a narrow channel through the coral reefs, and finally the Sea Venture sank so close to the beaches of a Bermuda island that all crew and passengers escaped safely to land.

the danger of storms in the North Atlantic was well known long before the Sea Venture was caught in a 1609 hurricane and wrecked on Bermuda

Source: Library of Congress, Americae sive qvartae orbis partis nova et exactissima descriptio (by Diego Gutierrez, 1562)

The other eight ships scattered due to the hurricane.

The Lion, Falcon, Unity, and Blessing arrived first at Jamestown, in August 1609. They were followed soon afterwards by the Swallow, Diamond, and finally the Virginia (which the colonists in the Popham Colony had built in 1607-1608). One other ship, a pinnace that had sailed with the fleet, disappeared.6

The seven ships of the fleet who reached Jamestown in 1609 brought 300 or more new colonists, but most of their supplies had been ruined in the hurricane. As a result, the Virginia Company's largest resupply effort turned into a drain on the colony's scarce resources. The ships had been well supplied before leaving, but the new colonists arrived with inadequate food to survive through the winter - and arrived so late in the growing season that there was not sufficient time to plant a new crop.

Bermuda is about 700 miles from the Virginia coast

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The leaders in the colony knew that a Third Supply was coming. Captain Samuel Argall had arrived by July of 1609 with news about the planned expedition, as recorded by John Smith:7

The colonists who had survived long enough to meet Captain Argall expected the Virginia Company to send food along with new colonists. He arrived after the last planting of corn; no one planted extra crops in Virginia in anticipation of having to feed new arrivals. At the same time, an extraordinary drought (the worst in over 700 years) was limiting the capacity of Native Americans near Jamestown to accumulate a food surplus to survive through the winter of 1609-10.8

Most of the 1609 resupply fleet arrived before John Smith's one-year term as president of the council expired September 10, 1609. However, the Sea Venture carrying the new leaders to replace Smith and the council only made it to Bermuda. Instead of arriving at Jamestown in in July, 1609, Lieutenant-General Thomas Gates was marooned. Gates and everyone else on the Sea Venture ended up alive thanks to strenuous efforts during the hurricane to keep the ship afloat, the seamanship skills of Admiral George Somers and the crew, and the good fortune to discover a navigable channel through the reefs - but they were not in Virginia.

Also stuck in Bermuda was the paperwork terminating the role of the council. Smith refused to accept that his role was ended, perhaps because those who did make it to Jamestown included his old rivals Gabriel Archer, John Ratcliffe, and John Martin.9

The newcomers led by Archer and Ratcliffe designated Francis West (brother of Lord De La Warre) as president to replace John Smith, but Smith claimed he was still in charge. As a maneuver to resolve the leadership impasse as well as to relieve the burden on food supplies at Jamestown, West took 120 men to the Fall Line and built a fort on the flood plain.

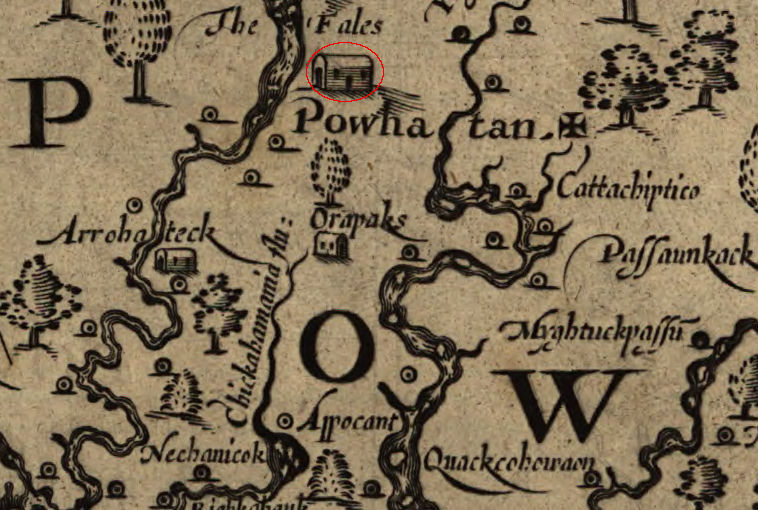

On a hill near West's chosen location was the Native American town where the weroance was Parahunt, a son of Powhatan. Parahunt objected to the English settling so close to his town, but John Smith arrived to check on conditions and was able to negotiate a deal.

John Smith's map of Virginia locates Parahunt's town east of downtown Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

Smith came upriver with just five people. One was a 14-year old named Henry Spelman who had just arrived in a resupply ship that made it through the hurricane. Smith purchased the site of the town above the flood plain, and as part of the deal "gave" Spelman to Parahunt to become an interpreter.

Francis West had moved upstream from Jamestown to reduce the conflict with John Smith, since Smith had refused to yield his authority as president of the council. West did not appreciate Smith meddling in the decision on where to locate the settlement at the Fall Line, and refused to move to the site on the hill that Smith had acquired from Parahunt and named Nonsuch.

To force West to move, Smith seized all of the settlement's vessels with food supplies. In response, the colonists raided Parahunt's food plots, generating conflict with the Native Americans. Smith started to go back downstream to Jamestown, the Native Americans attacked the colonist's settlement on the flood plain, and Smith returned to negotiated a peace. He promised the English would move up the hill.

However, Francis West directed everyone to return to the original site on the flood plain. Smith was unable to get West to reconsider, so he headed back to Jamestown. On that trip downriver, his thigh was burned when a spark dropped onto the gunpowder bag tied around his waist. Smith had to leap into the James River to extinguish the fire, and then had to be rescued from the river before he drowned. Smith's burn could have been an accident or an attempted assassination.

Smith never relinquished his claim to be president of the council. John Martin schemed with him to become president for one day and resign, so Smith could re-assume his role after his one-year term expired in September, 1609. Despite that arrangement, the gunpowder wound caused John Smith to sail home to England in October 1609.

George Percy then replaced Smith as president of the council. Smith got on the ship that was returning to England, Percy got off that ship, and Percy ended up presiding over the colony during the Starving Time during the winter of 1609-10.

He sailed up the Chesapeake Bay to obtain corn from the Patawomeck in 1609, but instead of delivering that food to the starving settlers, West sailed back to England.

He may have been forced to sail across the Atlantic Ocean by mutineers on his ship. He returned to Virginia in 1610 with his brother, Lord De La Warre, and was appointed governor in 1627-1629. Obviously Francis West was not treated as a coward who had abandoned Virginia when the colony most needed his help.

George Percy wrote later that when Francis West brought his ship loaded with corn back to Point Comfort, the captain in charge of Fort Algernon told everyone about the hunger at Jamestown. Instead of hurrying upstream to feed the colonists:10

the Spanish had known of Bermuda for a century before the English were shipwrecked there, but had no reason to establish a colony there

Source: Justin Winsor, Narrative And Critical History Of America (map by Peter Martyr in 1511, on p.110)

If Lieutenant-General Thomas Gates had arrived at Jamestown on the Sea Venture in August 1609 rather than been trapped on Bermuda, the Starving Time might have been minimized or avoided. If Gates had arrived in August, 1609,, there would have been no doubt regarding who was the official leader in Jamestown during the winter of 1609-1610. Gates had clear authority; there would have been no need to resolve conflict between West and Smith.

(In the world of "what if's:" If Thomas Gates had arrived to serve as governor in 1609, then more-assertive leadership might have led to increased seizure of Powhatan's corn, or greater dispersion of the colonists who ended up starving at Jamestown. Colonists spread out to the southern shore of the James River or even the Eastern Shore might have survived on oysters and other seafood, as did the colonists who wintered in Kecoughtan. John Smith might have stayed in Virginia under the command of Gates, explored further up the Susquehanna or Potomac rivers, or even traveled far beyond the Fall Line to interact with Siouan-speaking tribes such as the Monacan and Manahoac...)

The hogs provided plenty of food on Bermuda during the winter of 1609-10, in contrast to the Starving Time at Jamestown or when Henry May had been stranded there in 1593. After landing on Bermuda, Thomas Gates tried to plant a garden, but hogs broke in and ate the plants. Some of those hogs may have been the swine that were carried on the Sea Venture, but others were already on Bermuda.

William Strachey reported that hunters would take the ship's dog out, and he would grab the legs of wild pigs. With the dog's help, the hunters could bring back alive 30-50 pigs in a week to feed the castaways. The hogs were fattened on cedar and palm berries, and slaughtered when weather made it difficult to fish or capture tortoises.11

Despite abundant food, there was still conflict among the survivors of the Sea Venture. Sir George Somers was admiral for the fleet, but Sir Thomas Gates was supposed to be the governor once the fleet reached land. Though all 150 people had survived and reached land, they had not reached Jamestown. The journey had not ended, and it was not clear who should be in overall command.

The solution was for the survivors to split into two groups, living on separate islands with separate leaders. Gates commanded on one island, and Somers on the other, for 10 months.

Both leaders cooperated with each other to escape Bermuda and complete the journey to Virginia. Similar to Henry May's experience in 1593, skilled carpenters were among the shipwrecked crew. In 1609, the four carpenters guided construction of two pinnaces using wood, sails, and other parts from the wreck of Sea Venture. Gates guided construction of Deliverance on one island, while Somers built Patience on the other.

Gates experienced a mutiny. Some colonists decided that his authority had evaporated when the trip ended in Bermuda, and there was no obligation to obey him on the island. Gates pardoned two of the ringleaders leading the opposition to his authority. Henry Paine was accused of treason, and did not request pardon. Instead, he:12

The Deliverance and Patience left Bermuda on May 10, 1610. Seven people had died during the 1-month stay on Bermuda, including John Rolfe's child. Powhatan's envoy Namontack died under unknown circumstances. He may have died in an accident while hunting/fishing, or (as claimed by John Smith) he may have been murdered by his companion Matchumps.

In his 1611 play The Tempest, Shakespeare may have based his character Caliban on Namontack and Matchumps, and tried to help the Virginia Company by creating a happy ending. The Earl of Southampton, who invested heavily in the Virginia Company, had been an earlier patron of Shakespeare. At a time when there were no newspapers and rumors about Virginia emphasized the struggles of the venture, a play which presented colonization in a positive light provided useful "spin" for the investors.13

reports regarding the wreck of the Sea Venture may have inspired William Shakespeare to write "The Tempest" in 1611 (Prospero and Miranda are the characters on the right)

Source: Library of Congress, Shakespeare - Tempest, act 1, scene 1 (based on painting by George Romney)

The two pinnaces built on Bermuda took 11 days to sail the last leg of their trip from Bermuda to the Chesapeake Bay, and two more days to reach Jamestown on May 23, 1610. Just before the two ships sailed, three men ran away from the English camps; they did not want to sail away and serve as indentured servants for the Virginia Company at Jamestown.

The mutineers remained on the island with plenty of food, comfortable weather, and no one to order them to do any work. Washington Irving described them as the "Three Kings of Bermuda."14

After the Deliverance or Patience arrived, Gates learned how many in Jamestown had died during the Starving Time in the winter of 1609-10. After consultation with George Percy and the council, only Captain John Martin recommended staying in Virginia. Gates determined to abandon the colony and have everyone return to England.

There was food for only 16 days, which was not enough food to get everyone across the Atlantic Ocean. Like Henry May and the French with whom he was shipwrecked on Bermuda in 1593, Gates and Somers planned to sail to Newfoundland. Their hope was that English vessels in the fishing fleet there would have adequate supplies to support all the evacuating colonists.15

Gates and Somers knew they lacked enough food to sail directly back to England 1610, and planned to sail to Newfoundland to get supplies from English fishing vessels

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

On June 7, 1610, every English colonist (except those at Fort Algernon/Hampton and those who had fled to Powhatan and were still alive in one of his towns) got on board Discovery, Virginia, Deliverance, or Patience and sailed down the James River. The ships were near Mulberry Island (modern Fort Eustis) on their way home when on June 8 they met a skiff from Lord De la Warre's ship. The governor had arrived at Point Comfort on June 6 with supplies and more colonists.16

Lord De la Warre directed everyone to return back to Jamestown. The fort had not been burned when the colonists left, but required major repair after the Starving Time winter. If Powhatan had directed the wooden structures at Jamestown to be burned after the English sailed away, those orders had not been implemented before the colonists sailed back upstream.

The new governor had an obvious desire to ensure enough food was available to survive through the upcoming winter of 1610-1611. Captain Robert Tyndall was directed to take the Virginia to catch fish in the Chesapeake Bay between Cape Henry and Cape Charles.

Sir George Somers proposed that he sail back to Bermuda to get hogs, a trip that would give Somers another opportunity to be in charge during a voyage rather than be subordinate to a governor who had full authority on land.

On June 19, less than two weeks after Lord De La Warre's arrival, Somers took the Patience and Samuel Argall took the Discovery on what was supposed to be a trip to Bermuda.

The plan was for the two ships to return with a load of live hogs. Powhatan was blocking efforts to hunt deer and the English were unsuccessful in their efforts to catch fish in the James River, but Bermuda could provide meat for the colony.

After Somers and Argall got their ships through the Chesapeake Bay and out into the Atlantic Ocean, the wind blew them north. The Patience and Discovery were carried towards the Newfoundland fishing grounds, where the two ships were separated in a fog.

Captain Argall tried fishing in the North Atlantic to gather food before returning to Virginia at end of August. Captain Somers sailed south to Bermuda, the original destination. Somers considered starting an independent colony there, separate from the one in Virginia under Lord De la Warre. He showed little intention of returning to Virginia before he died on November 2.

His men removed the heart from the body of Captain Somers. It supposedly is buried on Bermuda, though the rest of the body was embalmed in a barrel of alcohol. The sailors sailed Patience to England rather than return to Jamestown. The Virginia colonists did not get any Bermuda hogs in 1610.17

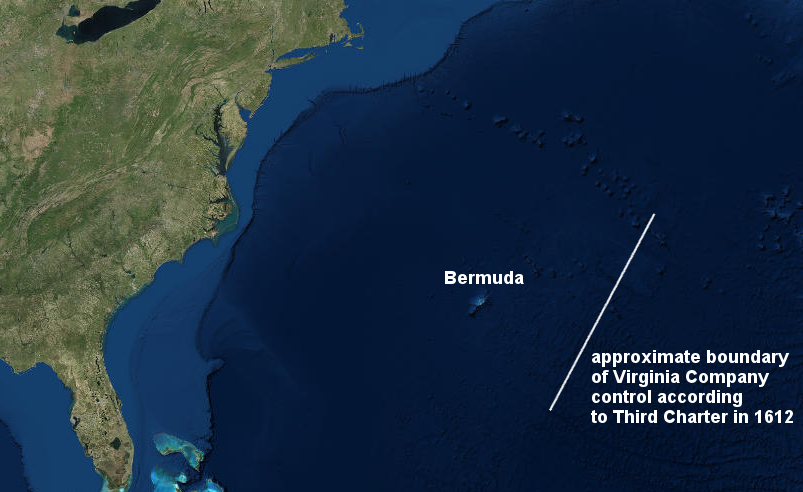

Reports of abundant food on Bermuda from the shipwrecked colonists contrasted clearly with reports from Jamestown. The Virginia Company decided to colonize the island and got King James I to grant a Third Charter in 1612 to expand where settlement was authorized. The king extended the colony's eastern boundary from 100 miles to 300 leagues (roughly 1,000 miles) into the Atlantic Ocean:18

the Third Charter issued on March 12, 1612 (1611, according to the Old Style calendar) gave the Virginia Company control over all islands within 300 leagues of the colony's coastline, thus ensuring Bermuda would be included

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Despite the good news about Bermuda, the Virginia Company still had great difficulty raising money. It was a private corporation not subsidized by the king, and to attract new investors the Virginia Company chose to sell shares separately for essentially a Bermuda subsidiary. Splitting the interests of the different investors started on a path that led to authorization later of "private plantations" in Virginia, and ultimately dissolution of the Virginia Company in 1624.

The experience on Bermuda may also have shaped the evolution of another colony.

When the Mayflower sailed from Plymouth, England in 1620, it was headed to Virginia. The Separatists (later called "Pilgrims") had migrated in 1608 to the Netherlands, and a year later settled in the city of Leiden. By 1620, the religious Separatists feared they would lose their English culture. They also saw threats to their freedom of worship when the leaders of the Netherlands negotiated deals with England and when Catholic Spain threated a new invasion.19

The Separatists arranged for permission to leave England and cross the Atlantic Ocean in order to settle within the Virginia boundaries. They were aiming for the northern edge, to get as far away from Jamestown as possible. According to the Virginia Company's 1612 charter, the mouth of the Hudson River was within of the colony of Virginia. The Mayflower ended up reaching land at Cape Cod, north of the 41° line of latitude defined as Virginia's northern boundary. Those on board chose to land there, where they had no authorization, rather than fight storms to sail further south to the intended destination.

The Separatists who had organized the expedition had picked up a set of "Strangers" in London to help pay the cost of the trip. Both groups may have been concerned that a decision to go ashore in an unauthorized area could weaken the legitimacy of leadership in the new settlement. The Mayflower Compact documented how the colonists would govern themselves, and also documented the original destination of the ship that arrived in Massachusetts in 1620 (emphasis added):20

It is possible that the Stephen Hopkins who is known to have been on the Mayflower might be the very same clerk who created confusion regarding the authority of Governor Gates in Bermuda in 1609-10. If so, his earlier experience might have stimulated those who landed outside the boundaries of any authorized colony in 1620 to write and sign a specific compact that clarified who would have official authority.

During the American Revolution, Bermuda "rescued" the rebellious colonists once more. In July 1775, after the Battle of Bunker Hill, George Washington had the British trapped in Boston but his soldiers lacked gunpowder. The British had restricted imports before the war broke out, and the colonists had only one powder mill (in Franklin, Pennsylvania) with significant production capacity. Washington's 14,000 men had only 36 barrels of powder, enough for just nine bullets per soldier.

The Bermuda colonists were sympathetic to the Americans. Bermuda imported 80% of its food from North America, and the Continental Congress's ban on exports to British-controlled territory would damage its economy and food security. However, the Bermuda settlers were unable to join in rebellion because the British Navy could easily capture the island.

The solution was to arrange for Bermuda sympathizers to steal the gunpowder stored in the magazine on the island and ship it to the Americans, who in exchange would allow trade to continue. The head of the Bermuda Assembly contacted his son in Virginia, St. George Tucker, who alerted Thomas Jefferson about the opportunity to exchange gunpowder for trade rights.

The magazine was emptied secretly on the night on August 14, 1775 and put on board an American ship. The next morning the Bermuda governor sent a ship after the American vessel, but the gunpowder reached Washington's army and lasted until the summer of 1776. Though the Americans allowed free trade between Bermuda merchants and the colonies, the royal governor finally stopped it by licensing privateers to seize all such vessels.21

tip of Cape Cod, first landing spot of the Separatists in 1620 (outside the boundaries of the Third Charter, and 13 years after Jamestown was settled)

Source: NationalAtlas

a replica of the Deliverance, originally constructed in 1609-10 to sail from Bermuda to Jamestown

Source: Toronto Public Library, The Deliverance

the Popham colony started by the Plymouth Company failed, leaving the Virginia Company with no competition in England except Bermuda until 1620

Source: The Southern States of America (published in 1909)