Tobacco Markets in Virginia

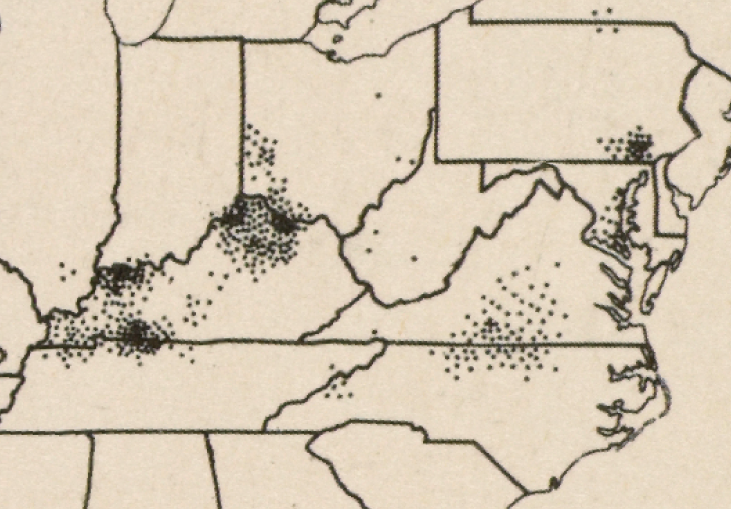

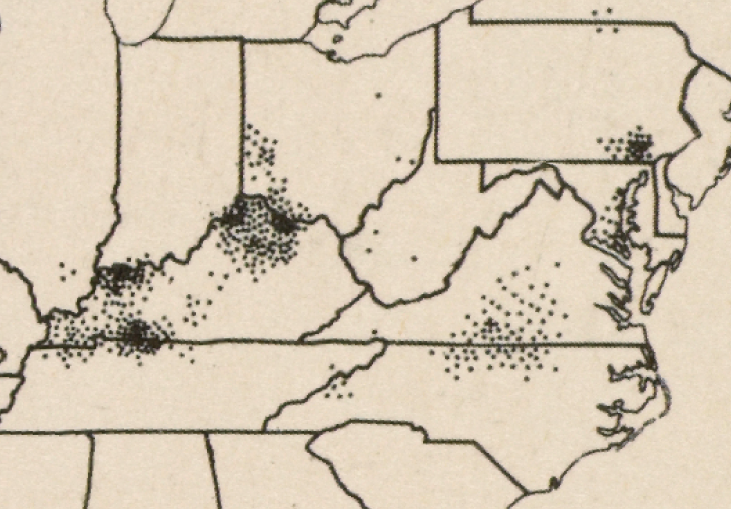

tobacco production was concentrated in Virginia and Kentucky in 1889, but then expanded into southern states and markets developed south into Florida

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Tobacco, 1889 (Plate 143g, digitized by University of Richmond)

Congress passed the Tobacco Inspection Act in 1935. As described by the Agricultural Marketing Service:1

- This act established the framework for development of official tobacco grade standards, authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to designate tobacco auction markets where tobacco growers would receive mandatory inspection of each lot of tobacco to determine its grade and type, and provided for the distribution of daily price reports showing the current average price for each grade. As a result of these services, tobacco growers and buyers know the true grade of tobacco being marketed and the approximate value of that grade.

If you could bring colonial governors in Virginia back to life, those from the 1680's onward would immediately recognize the value of that legislation. Many meetings of the House of Burgesses focused on how to stabilize the quality of tobacco so all plantations could receive a better price. The colonial government designated the location of official tobacco inspection stations effectively, starting in 1730, but the standards were not applied consistently enough and production was not limited sufficiently enough to raise prices as desired.

None of Virginia's original "tobacco towns" on the Chesapeake Bay are still places where farmers sell tobacco to processors. The area where tobacco was grown migrated into the Piedmont, and the tobacco markets moved there too.

In the 1700's, tobacco inspection stations were established in Tidewater. Tobacco that failed inspection ("trash" tobacco) was destroyed, so after the 1730's buyers could trust that a hogshead granted an inspection certificate had met a minimum quality standard.

Alexandria developed where the Hunting Creek warehouse had stored tobacco since Hugh West built it in 1732

Source: City of Alexandria, The Town of Alexandria: A Major Trading Place (1749-1860)

Farmers took their inspection certificates to nearby towns and sold the paper. That transferred ownership of the hogsheads - which were still stored in a warehouse at the inspection station. Buyers purchased tobacco inspection certificates without seeing the actual tobacco, then collected their hogsheads from the warehouse. Certificates did not clearly identify different grades of tobacco, so buyers could end up buying hogsheads of higher-quality and lower-quality tobacco at the same price.

Smart buyers began to visit the inspection stations and personally examine individual hogsheads, before buying certificates. That allowed buyers to choose the prime hogsheads, but farmers were then forced to sell the remainder at a discount. As buyers sought to identify higher-quality tobacco, farmers sought a premium in price.

By the 1830's, a new process for buying/selling tobacco had evolved. Warehouse operators in tobacco-growing regions created competitive auctions, where farmers could display their crop to buyers from different companies and obtain the best bid. Large cities like Lynchburg and Danville ended up with multiple warehouses hosting auctions, and warehouses emerged in small towns like South Boston and Chase City as well.2

Burley tobacco, grown primarily west of the Blue Ridge, was harvested by cutting the stalk at ground level, then hanging the stalk with all the leaves attached in a barn to dry. The wooden boards on the sides of the drying barn would be separated far enough to ensure easy air flow, so the burley leaves would dry before mold could grow.

Flue-cured or "bright" tobacco was grown primarily east of the Blue Ridge. Individual leaves were picked from the stalk as they ripened from the bottom up, which required multiple trips through the fields and back-breaking effort to harvest leaves one at a time.

After each harvest cycle, about five leaves were strung together into a bundle and the bundles were hung in a small air-tight shed. A fire outside the shed generated heat, which a pipe (flue) transferred into the shed (so flue-cured tobacco was never exposed directly to smoke). In several days of slow cooking, the leaves dried and turn bright yellow.

Flue-cured "bright" tobacco leaves and air-cured burley were brought to a warehouse in burlap sacks weighing 200 pounds, and the sacks were lined up on warehouse floors in long rows. Auctioneers walked down the rows chanting prices in a distinctive sing-song voice, spurring tobacco buyers for different companies to bid for each pile. The sale continued with the auctioneer and bidders walking without breaking stride, and pile after pile was sold to the highest bidder.

warehouses hosted tobacco auctions, where farmers sold their crop to the highest bidders

Source: Boston Public Library, Tichnor Brothers Postcard Collection, Tobacco auction, Danville, Va.

as tobacco buyers walked along lines of sacks of tobacco, the auctioneer generated bids for each sack on the warehouse floor

Source: Library of Congress, Auction sale in tobacco warehouse, Danville, Virginia (by Marion Post Wolcott, October 1940)

After each pile was sold, an employee of the warehouse dropped a copy of the sale ticket on the pile. A crew of laborers (typically young black men from the local area) spent the afternoon carrying the burlap sacks full of tobacco off the floor to the storage area assigned to each company. The sacks would then be loaded on railroad cars (later, on trucks) and carried to factories in North Carolina or Richmond. As warehouse floors were cleared, new rows of tobacco would be lined up for the next sale day.

tobacco warehouses in the 1800's and 1900's were community centers, similar to grist mills

Source: Library of Congress, Farmers sitting around and talking inside tobacco warehouse while waiting for auction sale

Starting in the 1990's, the warehouse sales program changed. The Federal government eliminated the quota system that guaranteed a minimum price, but limited how much tobacco a farmer could raise.

Instead of farmers selling their crops at competitive auctions, they contracted with tobacco processing companies like Phillip Morris USA to grow a crop of tobacco that met the company's specifications, at whatever price was fixed in the contract. Farmers with direct sale contracts packed their crop into large half-ton bales for shipment directly to the company's receiving stations, bypassing the auction markets.

Traditional warehouse auctions declined, and by 2000 Virginia had only 6 tobacco markets still active in selling flue-cured tobacco. Burley tobacco was sold in Abingdon, Gate City, and Pennington. Sun tobacco was sold at Farmville, and fire-cured tobacco was sold at Blackstone and Farmville.

Warehouse marketing, with auctioneers selling tobacco to the highest bidder, has been almost completely replaced by direct sale contracts between tobacco companies and tobacco growers. The loss of the competitive sales at warehouses left farmers with no easy way to sell whatever excess tobacco they raised in a good year, beyond their contracted amount. In bad years, farmers would end up with still-useable tobacco that did not meet their contracted company's specifications.

Warehouses are now making a small comeback, giving farmers an outlet for selling their poor-quality tobacco and excess amounts of high-quality tobacco. In 2012, the Piedmont Warehouse re-started competitive auctions in Danville.

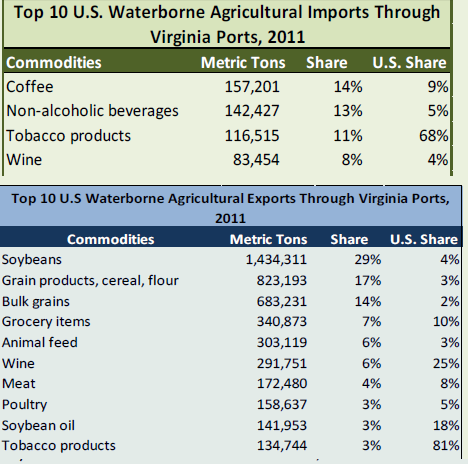

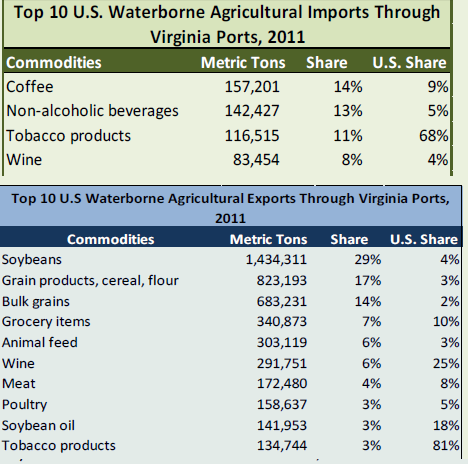

Not all tobacco grown in Virginia is processed in Virginia. Processed (and some unprocessed) tobacco is still a major export crop, but it is also one of the main imports through the Port of Virginia. The United States typically exports high-value cigarettes and other tobacco products and some high-value leaf, while importing from overseas some specialized tobaccos to flavor cigarettes plus much low-cost "filler" tobacco.

John Smith negotiating for corn

Source: USDA Agricultural Marketing Service, Export/Import Profile

References

1. "Commodity Areas - Division Mission and History," Agricultural Marketing Service, US Department of Agriculture, (last checked October 26, 2013)

2. Joseph Clarke Robert, "Rise of the Tobacco Warehouse Auction System in Virginia, 1800-1860," Agricultural History, Vol. 7, No. 4 (October 1933), http://www.jstor.org/stable/3739353 (last checked October 26, 2013)

3. "Where To Find An Auction For 2013," Tobacco Farmer Newsletter, June 3, 2013, http://modtob.blogspot.com/2013/06/an-auction-at-old-belt-tobacco-sales.html (last checked October 26, 2013)

Virginia Agriculture

Virginia Places