Tobacco in Virginia

cartouche on the lower right-hand corner of the Fry-Jefferson map of Virginia,

showing tobacco hogsheads being inspected and shipped overseas

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. Drawn by Joshua Fry & Peter Jefferson in 1751

There are multiple species of tobacco, which is in the same botanical family as eggplant, tomatoes, potatoes, and chili peppers. Indigenous ("wild") species in western North America include Nicotiana quadrivalvis, Nicotiana attenuata, and Nicotiana obtusifolia, and across the continent 100 plant species have been smoked.

Tobacco is not native to Virginia, but it was being grown in North America by Native American farmers about 3,000 years before Jamestown was settled.

Nicotinia rustica and Nicotiana tabacum originated in South America. These species were domesticated in the Andes of Peru and Ecuador perhaps 6,000–8,000 years ago, producing higher nicotine content and larger leaves. Over 80 native species were domesticated in Amazonia before Europeans arrived in the New World. With the help of agriculturalists, Nicotinia rustica reached Virginia about 2,500–3,500 years ago, making it one of the first domesticated plants.

The Spanish were the first Europeans to encounter tobacco. When they met the Taino Arawak in 1492 on the Bahama Islands, Columbus's men got a chance to smoke and perhaps chew tobacco. The Spanish preferred the "smooth" taste of Nicotinia tabacum compared to Nicotinia rustica, but began growing both species on Caribbean and South American plantations in the 1500's.1

John Rolfe is credited with obtaining the seeds of Nicotiana tabacum, perhaps before sailing in 1609 to Virginia via a smuggler who had acquired the seeds from a Spanish plantation on Trinidad or Venezuela. It is also possible that he collected the seeds while shipwrecked on Bermuda in the winter of 1609-1610. He shipped his first crop to England on the Elizabeth; it arrived there on July 20, 1613.

Thanks to Rolfe, Virginians grew a species of tobacco that competed successfully against the Nicotinia rustica being shipped to Spain and distributed in Europe. In 1617 Virginians shipped 20,000 pounds of tobacco. That was doubled to 40,000 pounds in 1618 and increased to 60,000 pounds in 1622.

In the 1650's, Edward Digges developed a strain of "sweet-scented" tobacco on his York River plantation. That milder leaf reflected the character of the sandy soil in which it was grown. Virginia planters later discovered that European customers preferred the stronger "Orinoco" strain and it became the dominant crop, but the "E Dees" hogsheads initially attracted a higher price in London:2

- One shilling on the pound when other tobaccos brought not threepence...

Tobacco growing and processing dominated Virginia's economy for over three centuries, and transformed its landscape. Tobacco wears out the land, exhausting minerals and nutrients from the soil. The first Virginia colonists to acquire ownership of land were positioned to gain great wealth, permitting them to abandon old fields and plant in fresh soil that would produce great quantities of the crop.

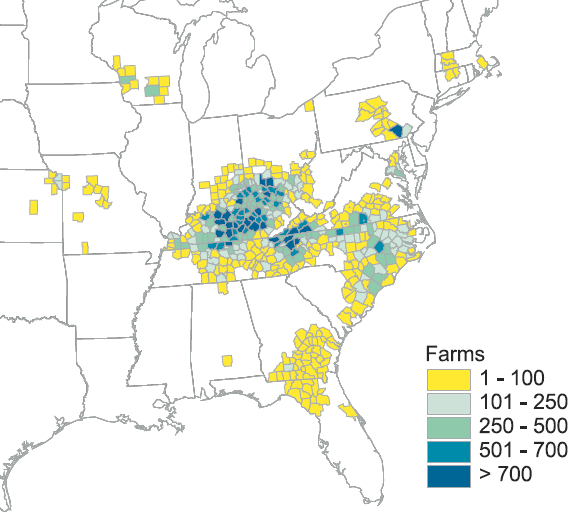

Source: US Department of Agriculture, Tobacco and the Economy: Farms, Jobs, and Communities (Appendix 2, Figure 2)

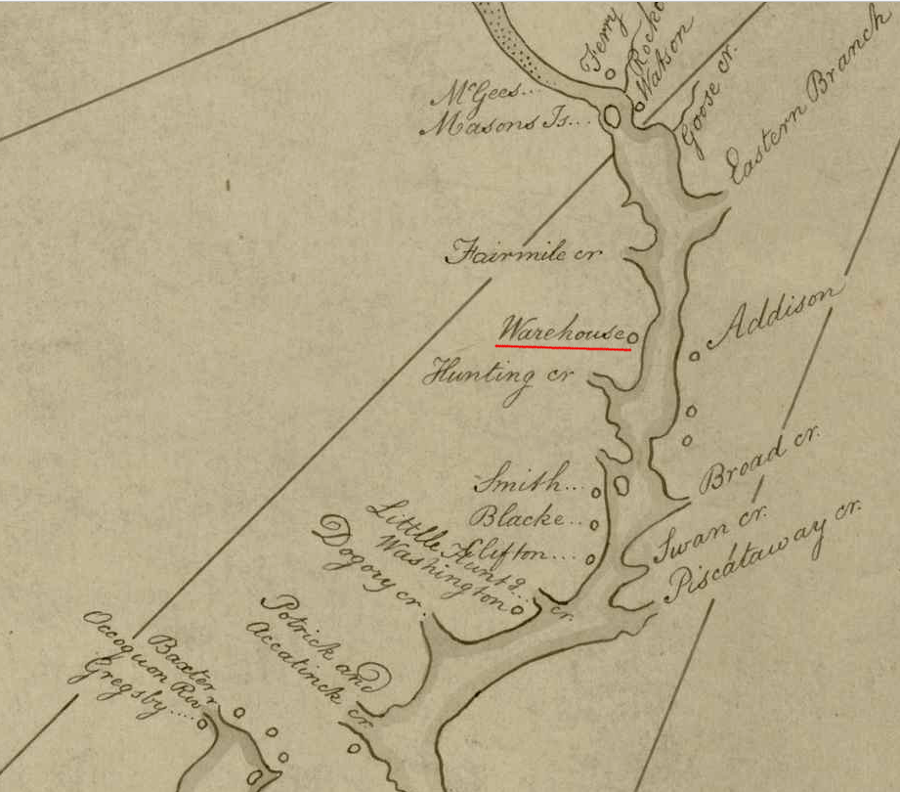

The hunger for new land was fundamental to Virginia's colonial claims to the Ohio River Valley and to Kentucky. Virginians seeking new places to grow tobacco created conflicts with Native American tribes long after Powhatan's paramount chiefdom had been subjugated and the Coastal Plain had been occupied by European trespassers. Early towns in Virginia, including Alexandria, developed at locations where tobacco inspection stations and warehouses were built.

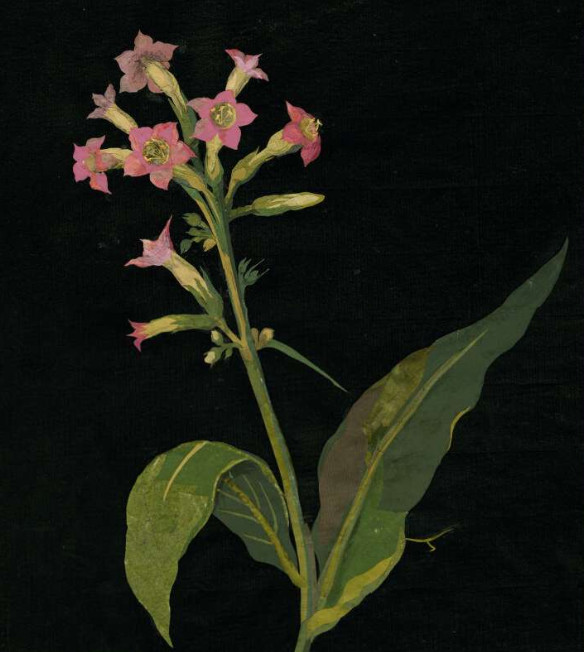

Growing tobacco is very labor-intensive. Flowers had to be removed in order to drive nutrients into growing bigger leaves. Picking leaves at separate times as they ripened might increase the quality of the tobacco, but the labor required for that work was not available in colonial Virginia. Until the development of flue curing after the Civil War, the entire plant would be cut down and dried before leaves were packed into hogsheads.

tobacco flowers drained energy from the leaves, but it was labor-intensive to "top" tobacco plants

Source: British Museum, Nicotiana Tabacum (drawn by Mary Delany, 1780)

In the 1600's the Virginia gentry who had acquired land needed to import a labor force. Imports of indentured servants were spurred by grants of headrights, but the supply of interested immigrants from England declined after the end of the English Civil War and restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660. Religious and economic refugees were recruited from France and what today is Germany in the 1700's, as were the Scottish settlers in Ireland who sought greater opportunity in the New World.

However, by 1700 it was clear that the Virginian leaders had committed to getting their labor from Africa. In the second half of the 17th Century the Virginia gentry institutionalized and expanded slavery for one primary reason: to obtain the labor needed to farm tobacco. Without tobacco, slavery in Virginia may have died out as the practice did in the northern states - and without the economic factor of slavery, Virginia might have chosen to stay with the Union rather than join the Confederacy in the American Civil War in 1861-65.

enslaved people did the hard work of planting, weeding, harvesting, packing, and shipping tobacco

Source: Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, Tobacco Production, Virginia, 1821

Tobacco seeds are very, very tiny. Tobacco seedlings are grown in seedbeds of very fine soil, then transplanted to farm fields in the late spring after all danger of frost is past. Each slave or indentured servant working on a tobacco plantation in colonial days may have planted and weeded about two acres of cleared land with 9-10,000 plants a year, requiring bending over perhaps 50,000 times.

Tobacco drained the soil of key nutrients, requiring labor to clear forests so tobacco could be planted in fresh soil. "Old fields" had to remain unplanted for one-two decades before soil fertility was restored naturally (unless fertilized with animal manure). The most economical way to grow tobacco was on large farms, where most of the acreage could be left unused for 20 years:3

- [B]ecause the main crops, tobacco for export and corn for subsistence, were very demanding of soil nutrients, they required long rotations after short use if the land was to regain its fertility without manuring. The planter could grow tobacco for three years, followed by another three of corn, which has a deeper root system than tobacco and hence draws on another layer of soil, but the land then had to lie fallow for 20 years before yields could once again be profitable.

- To maintain this rotation, the planter required 20 acres per hand, just for these two crops. Second, while seventeenth century planters introduced domestic livestock, they did not pen and feed it... and hence could not use animal manure. Long rotations were therefore the rule.

tobacco was air-dried before being packed ("prized") into hogsheads for shipping to England

Tobacco has been grown in nearly every Virginia county. Tobacco culture has evolved over the centuries, and has become an essential element of what makes Virginia unique. However, the tobacco-growing counties now are almost all in Southside and Southwest Virginia, and few urban Virginians have ever walked in a tobacco field, pulled suckers, topped plants, or even seen the crop harvested.

Today the process of growing tobacco is still labor-intensive, but profits from several acres of tobacco can exceed the profits from many more acres planted in corn or soybeans.

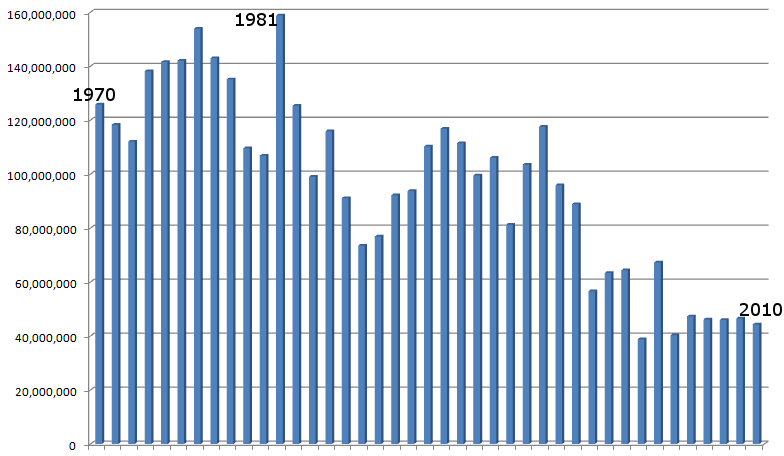

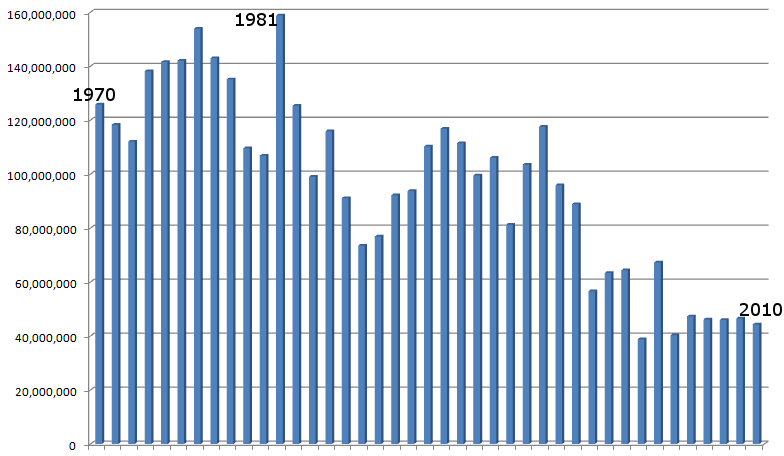

Nationwide, the annual tobacco crop was sold for about $3 billion in 1997, but the "value added" by processing it into cigarettes and other products was substantially greater - consumers spent $60 billion on tobacco products in 1998. Peak value of the tobacco crop was $3.5 billion in 1981, the same year as peak production. In 2010, the US tobacco crop was valued at $1.25 billion. Since 1970, Virginia's tobacco crop has ranged in value from a low of $61 million in 2005 to a high of $266 million in 1981. In 2010, value was $78 million.4

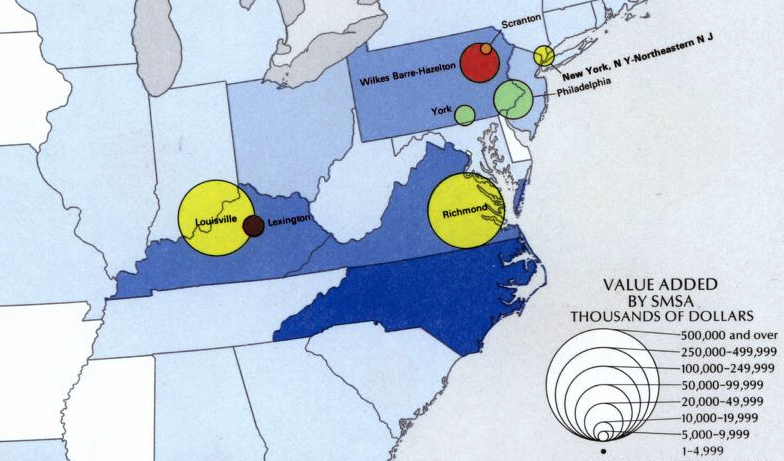

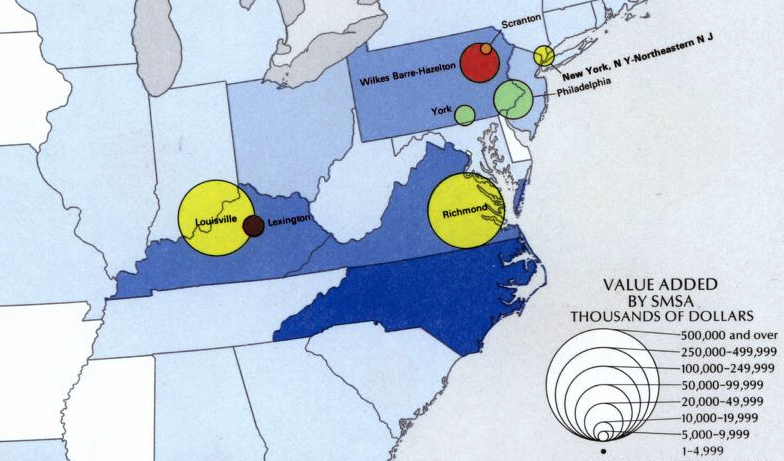

in 1963 bright tobacco processing was concentrated in the Richmond Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA), burley tobacco processing in Louisville, and cigar leaf wrapper processing in Pennsylvania

Source: Library of Congress, "The national atlas of the United States of America," Tobacco Manufactures

Different types of tobacco are grown in different places. In the United States, tobacco is a regional crop, concentrated in the Southeastern United States. Pennsylvania farmers grow cigar filler, while Connecticut River valley farmers produce the leaves used for cigar wrappers by growing tobacco plants under white cloth to reduce the number of spots from the sun and insects. Tobacco is also grown in large quantities in Zimbabwe, China - and especially in Brazil.

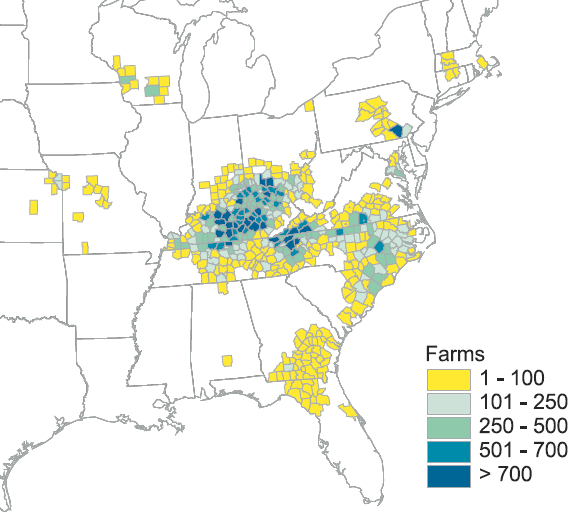

tobacco-growing counties in the United States

Source: US Department of Agriculture - Economic Research Service, Trends in U.S. Tobacco Farming (TBS-257-02, November 2004)

Cigarette, cigar, and pipe tobacco manufacturers blend different tobaccos to create unique tastes and burning characteristics. As described by a US Department of Agriculture report:5

- Tobacco is not a homogeneous product. The flavor, mildness, texture, tar, nicotine, and sugar content vary considerably across varieties or types of tobacco. Defining characteristics of different tobacco types include the curing process (flue-, air-, sun-cured) and leaf color (light or dark), size, and thickness. A given type of tobacco has a different quality depending on where it is grown, its position on the stalk (leaves near the bottom of the stalk are lower in quality), and weather conditions during growing and curing.

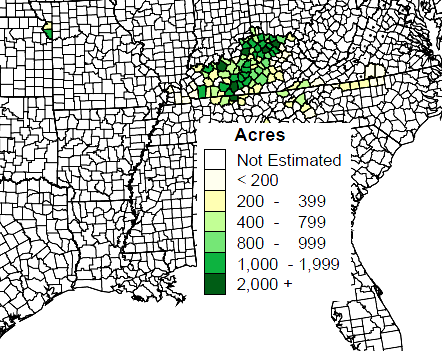

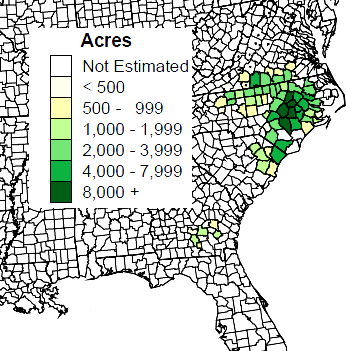

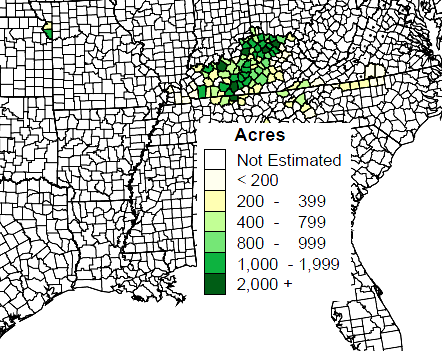

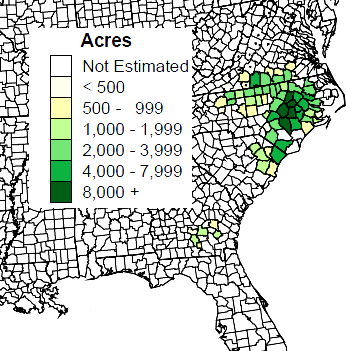

counties growing burley tobacco (left) are concentrated west of the Blue Ridge, and counties growing flue-cured tobacco (right) are concentrated east of the Blue Ridge

Source: National Agricultural Statistics Service

Burley is a dark leaf grown primarily in Kentucky and Tennessee, plus some southwestern Virginia counties (and starting in the 1990's, in Piedmont counties as well).6

stalks of burley tobacco were placed on sticks to wilt in the field, then air dry in the barn

Source: Library of Congress, Taking Burley tobacco in from the fields after it had been cut, to dry and cure in the barn, on the Russell Spears' farm, vicinity of Lexington, Ky. (by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1940)

Bright tobacco (also known as "flue cured" or "Virginia" tobacco) is grown in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain from Northern Florida to Maryland. Strip the paper from a cigarette today, and the different color of tobaccos inside are obvious. Typically the darker-colored tobaccos are burley and the lighter-colored tobaccos are "bright," but foreign tobaccos are also added to almost every cigarette. The use of Turkish tobacco led to one brand being named Camels. Many different brands use that same tobacco, blending it with other types in different ratios to create unique flavors.

Local regions in the Southeastern United States that grow bright tobacco are known traditionally as "belts." Tobacco used to be sold at auctions in warehouses in small southern towns. Auctions were held in sequence, moving north as the crop ripened from the "Georgia Belt" in August to the "Old Belt" in Virginia in late Fall.

tobacco barns in 1939

Source: Library of Congress, John D. Ferguson and son coming up road in wagon tobacco barns in the background. Route 57 going east from Chatham (1939)

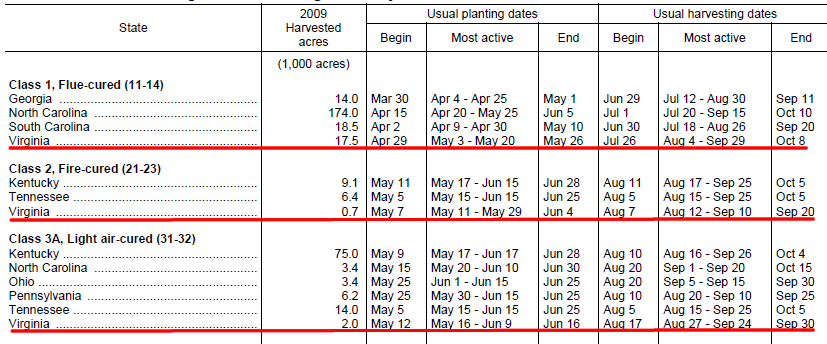

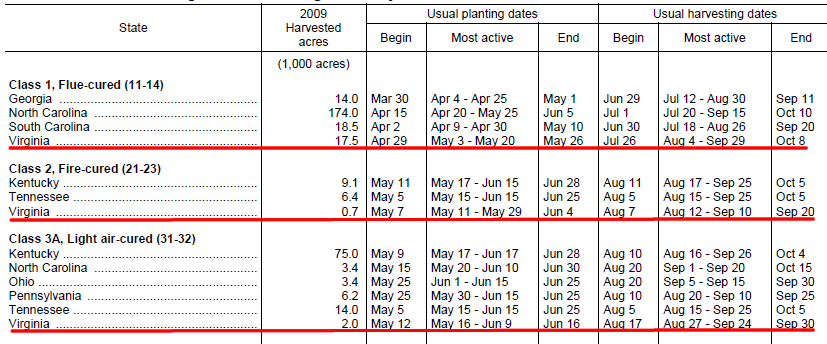

Climate plays a role. The harvest in Georgia is over by late August, but in Virginia the end of the harvest for flue-tobacco or "Type 11" tobacco is mid-October.

tobacco planting/harvest dates, starting in south and migrating north

Source: US Department of Agriculture, Field Crops Usual Planting and Harvesting Dates (October 2010)

Farmers would bring their crop to a warehouse, and bidders from different tobacco companies (such as Philip Morris) would walk along piles of tobacco arranged in long rows. An auctioneer would chant the bids until finally announcing the price at which each pile was sold.

The bidders walked at a steady pace, and it might take just 10-15 seconds at each pile until the auctioneer concluded his sing-song chant of the bids with "Sold American!" (if purchased by the American Tobacco Company, for example). A clerk trailing the bidders would write the price and the buying company on a ticket, which he would toss on each pile. After examining all the tickets on his piles, the tobacco farmer would discover if he had made a profit that year.

flue-cured leaves knotted into hands, piled on tobacco warehouse floor for auction

prior to being "prized" into hogsheads (visible in rear)

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries Digital Collections, Rarely Seen Richmond

The warehouse auction process has almost disappeared now. Farmers are contracting in the Spring with a specific tobacco company to sell the crop, eliminating the competitive bidding in the Fall. Small Virginia towns that had tobacco warehouses, such as South Hill, have lost both the economic activity of the crowd that came to auctions and an activity that reflected the unique culture of the tobacco growing community.

After a farmer sold his tobacco, the leaves were shipped to processing plants, where chopping and blending created different combinations with different flavors. Major centers of tobacco manufacturing were Lynchburg, Petersburg, and Richmond. After the Civil War, North Carolina emerged as the center of tobacco processing, and cigarette brands named after Winston and Salem commemorated manufacturing centers in that state.

One cigarette factory in Richmond remains, visible on Interstate 95 south of the James River. That facility is owned by Phillip Morris USA, a subsidiary of Altria. Altria sells Marlboro, which has 44% of the market in the United States. The company closed its North Carolina production plants in 2010, shifting production of cigarettes for European markets to non-American factories and placing all US production in Richmond. Altria also relocated its headquarters from New York to Richmond, making Richmond "Tobacco Town" again.7

Altria's plant along I-95, first built in 1973, now produces half of all the cigarettes sold within the United States, and that Richmond facility may be the largest cigarette production plant in the world. Competition for that title comes from cigarette manufacturing in China, where production of the dominant Hongta ("Red Pagoda") brand is concentrated in the city of Yuxi.8

Richmond is still dotted with old tobacco facilities. The Liggett and Myers cigarette manufacturing plant in downtown Richmond is now an office building. Tobacco storage warehouses on the slopes of Church Hill are being converted into housing for young, upwardly-mobile professionals. Twenty-five years ago, it was common in the early morning for the whole downtown to smell of ripening tobacco. The closest warehouses now are several miles south of town - as you drive by on I-95, look for the blue sheds with "Shh! Tobacco sleeping" sign.

declining Virginia tobacco production (in pounds), 1970-2010

Source: National Agricultural Statistics Service, Quick Stats

Four types of tobacco were raised by Virginia farmers, but one specialty version is no longer grown in sufficient quality to be recorded in the government statistics. Virginia tobacco farmers grow bright tobacco (classified by the US Department of Agriculture as flue-tobacco or Type 11) in what USDA calls the Piedmont District (basically Southside Virginia, east of the Blue Ridge).

Burley (Type 31) tobacco is grown primarily in Southwestern Virginia. The Blue Ridge separates the bright and burley regions. Until the mid-1990's, 98% of the burley in Virginia was grown west of Patrick County.

In addition, small amounts of tobacco classified as fire-cured (Type 21, cured with smoke) and sun (Type 37, cured in direct sunlight) are grown in Virginia. Sun-cured tobaccos, often grown in Turkey and the Balkans, are added to many types of cigarettes to add aroma.

Bright tobacco leaves are picked as they ripen, the bottom leaves first. The requirement to make multiple trips through the tobacco fields, to harvest leaves as they ripen, is one reason tobacco is still a labor intensive crop.

The picked leaves are flue-cured. A half-dozen or so leaves will be tied together at their base, and the bundles will be hung in air-tight barns. The barns are heated by propane burners located outside the barn, with flues carrying the heat into the barn to bake the leaves slowly. As the green tobacco leaves dry out and cure in the dry heat, the leaves turn yellow with brown "sugar spots."

Burley leaves are harvested all at once, by cutting the tobacco plant stalk at ground level. Leaves are left attached to the stalk, which is speared onto a stick and then hung in long rows at the top of barns to dry until brown. Burley barns are not air-tight, and the leaves dry in the cool autumn air without extra heat. Air circulation in the barn is increased by bending every other board away from the barn wall. Drying is essential to prevent the leaves from rotting, and ultimately to allow them to burn in cigarettes, pipes, cigars, etc.

burley tobacco air-curing in barn

Source: National Park Service

Fire-cured leaves are smoked in barns, in a process similar to smoking meat. Stalks are harvested similar to burley, so farmers make just one pass through the fields. Tobacco stalks are hung on racks, where leaves are exposed to several days of heat and smoke from hardwood fires.

Tobacco is often reported to be "the world's most widely cultivated non-food crop." Most Virginia farms do not grow tobacco, but it's a key crop for those who do.9

In the Piedmont District ("Piedmont" tobacco region as defined by the US Department of Agriculture - not the entire Piedmont physiographic province...), less that 10% of the farms had an allotment allowing them to grow tobacco. In 1996, however, that one crop "accounted for about half the gross value of production for the agricultural sector of the Piedmont region in 1996." Tobacco was grown on 10% of the average farm (29 of 290 acres) but generated 90% of the income for farms in that region.10

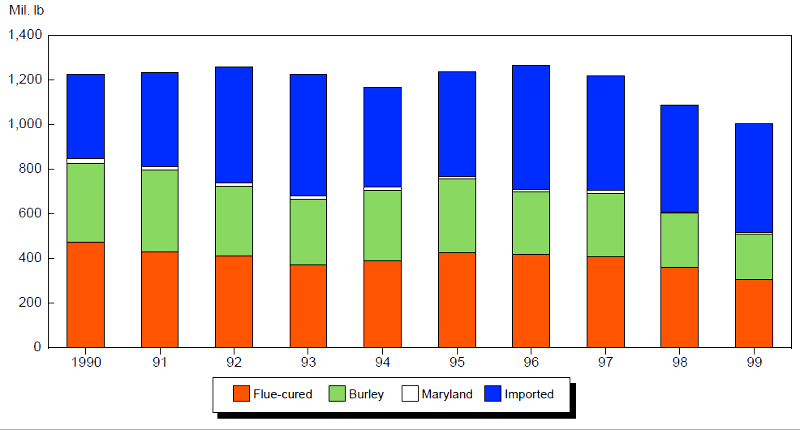

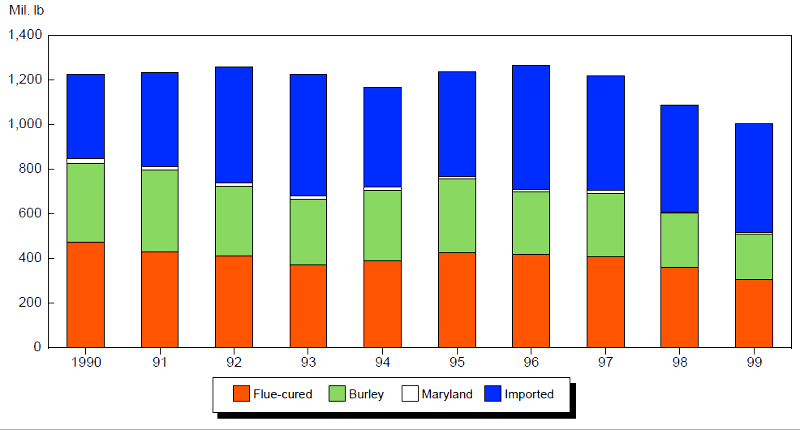

types of tobacco in cigarettes, 1990-1999

Source: US Department of Agriculture - Economic Research Service, Trends in the Cigarette Industry After the Master Settlement Agreement

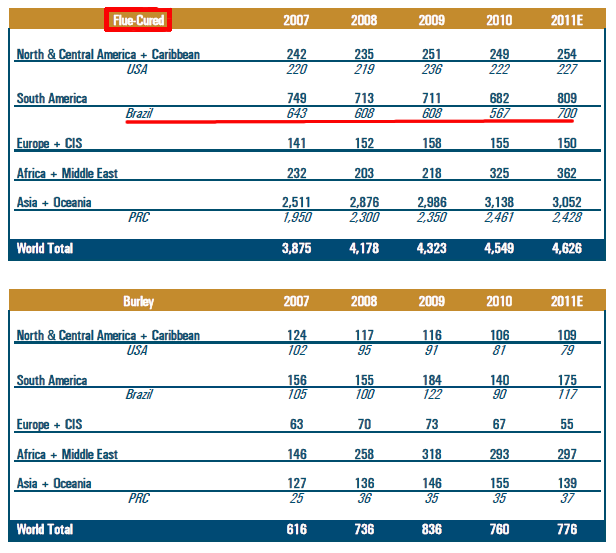

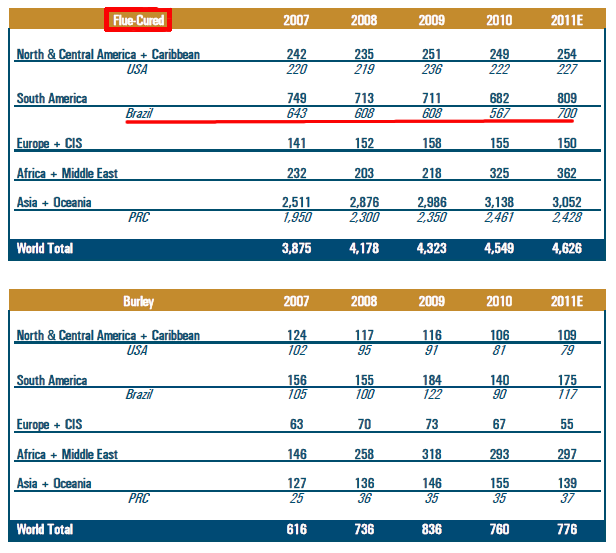

Unfortunately for Virginia farmers who appreciate the income from tobacco, the harvest is declining in quantity and value now. This is due in part because the supply of tobacco has increased as manufacturers - mostly cigarette companies - are importing cheaper tobacco from Africa and China and South America. Brazil is now the world's largest producer of flue-cured tobacco.

estimated leaf production (in million kilograms of uncured green tobacco)

Source: Universal Leaf Tobacco, World Leaf Production as of 4 August 2011

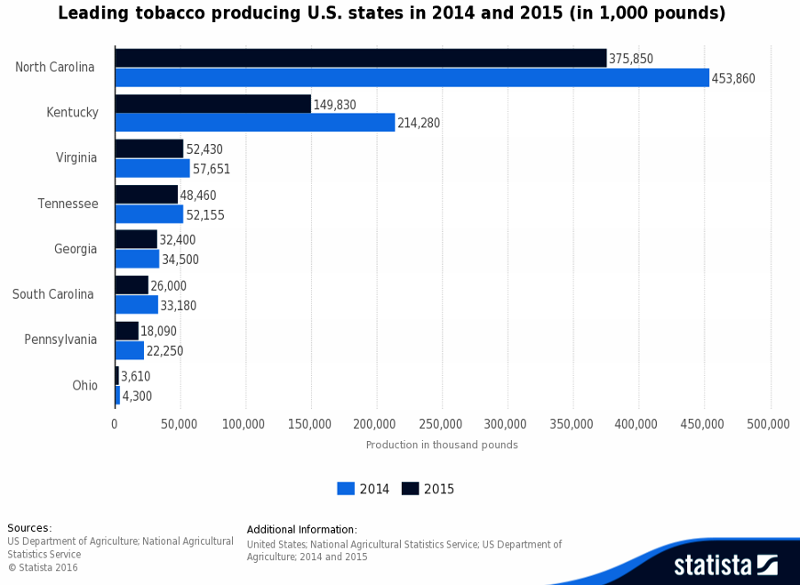

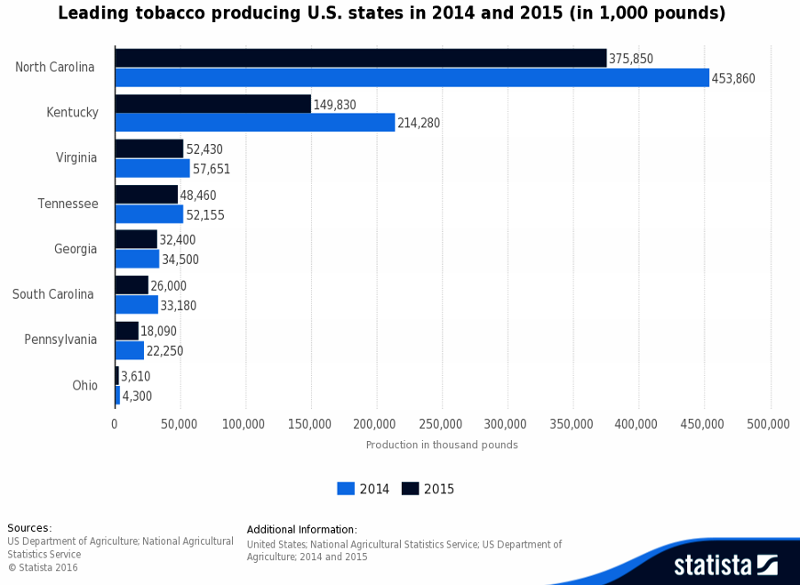

Virginia is not the #1 tobacco-growing state now

Source: Statistica, Leading tobacco producing U.S. states in 2014 and 2015 (in 1,000 pounds)

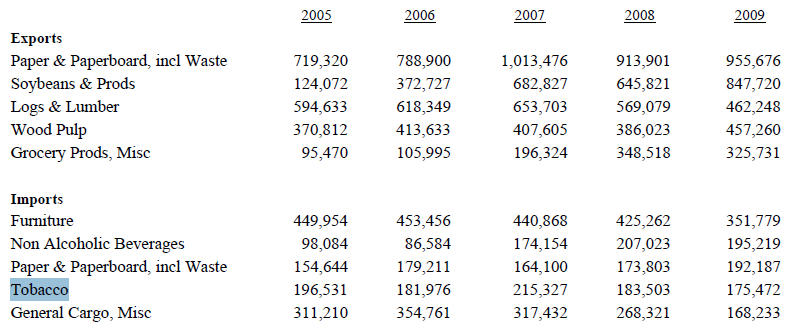

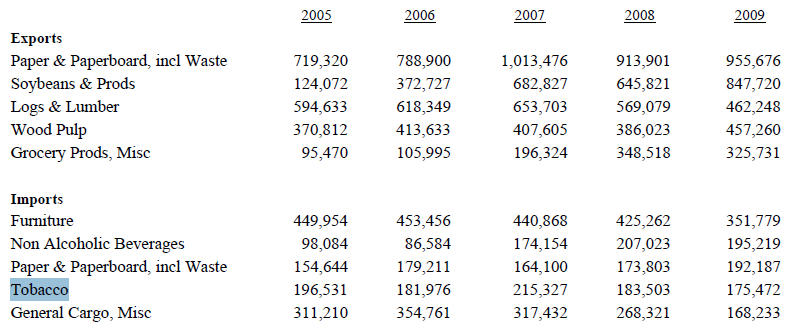

The manufacturers blend tobacco material from different locations to get the preferred combination for taste, burning rate, and cost. The use of imported tobacco is not new in Virginia. The logo for the Camel brand of cigarette was legitimately exotic. Turkish tobacco has added intense flavor to Virginia-made cigarettes for almost a century. Today, "unmanufactured tobacco" is one of the major commodities imported as well as exported through Norfolk.

tobacco: a major import commodity at Hampton Roads (in short tons)

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 20, 2010, p.92

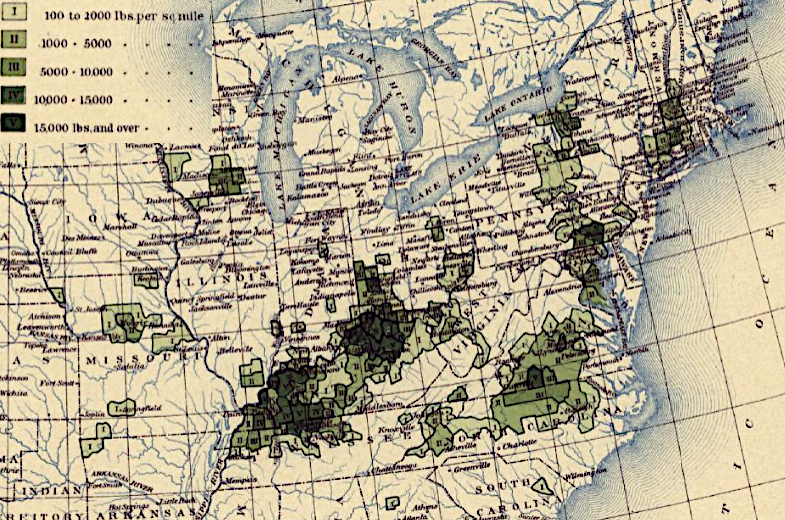

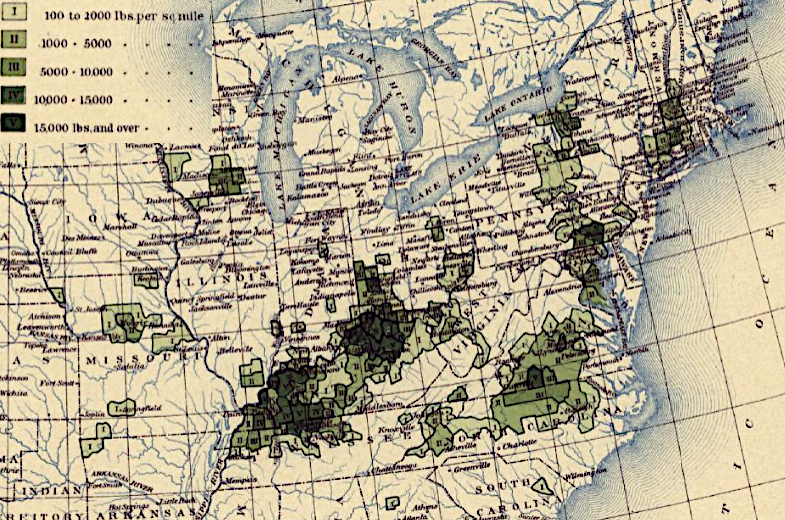

tobacco production by county, 1890

Source: Library of Congress, Statistical atlas of the United States, based upon the results of the eleventh census (1898)

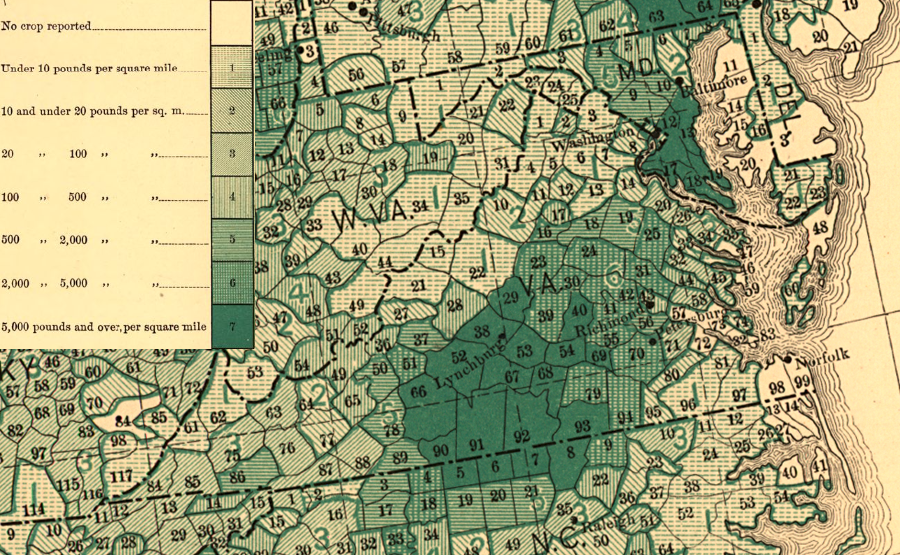

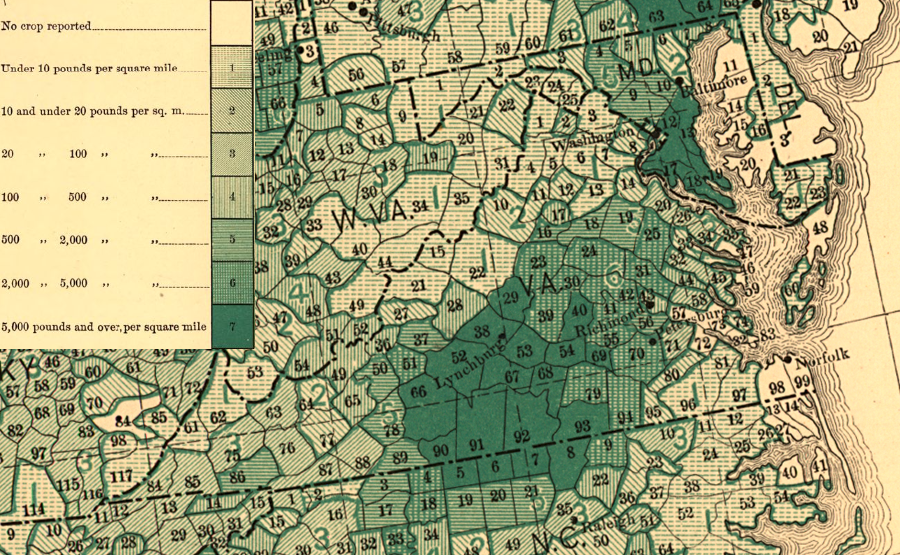

in 1880, tobacco was grown in many counties but the farmers in Southside harvested the greatest amount per acre

Source: Library of Congress, "Scribner's Statistical Atlas of the United States," Plate 110: Agriculture (Tobacco)

Links

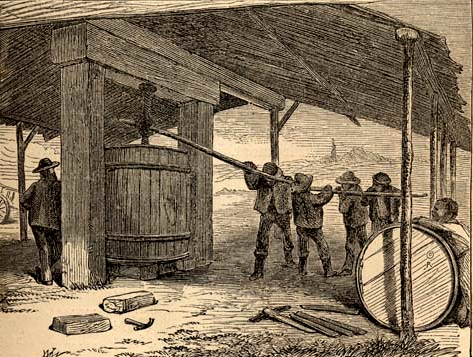

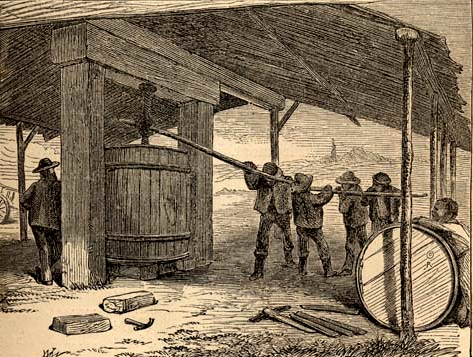

in the 1700's, tobacco was "prized" into hogsheads weighing 1,000 pounds for export to England

Source: The Great South; A Record of Journeys in Louisiana, Texas, the Indian Territory, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland (1875)

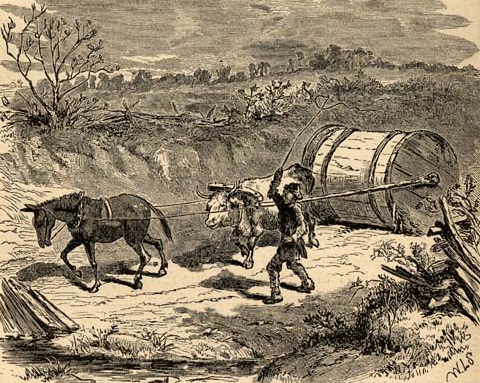

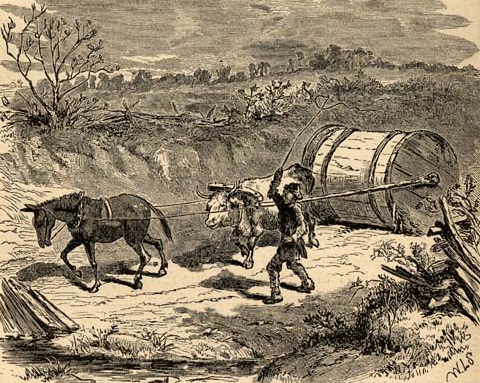

tobacco hogsheads too heavy to lift into wagons could be transported by "rolling roads" from farm to riverbank, for inspection (after 1730) and export

Source: University of North Carolina, The Great South; A Record of Journeys in Louisiana, Texas, the Indian Territory, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland (1875)

References

1. S. Carmody, J. Davis, S. Tadi, J.S. Sharp, R.K. Hunt, J. Russ, "Evidence of tobacco from a Late Archaic smoking tube recovered from theFlint River site in southeastern North America," Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, June 15, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.05.013; Shannon Tushingham, Charles M. Snyder, Korey J. Brownstein, David R. Gang, "Biomolecular archaeology reveals ancient origins of indigenous tobacco smoking in North American Plateau," PNAS, Volume 115 Number 46 (October 29, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813796115; Charles R. Clement, William M. Denevan, Michael J. Heckenberger, André Braga Junqueira, Eduardo G. Neves, Wenceslau G. Teixeira, William I. Woods, "The domestication of Amazonia before European conquest," Proceedings of the Royal Society, August 7, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.0813 (last checked February 16, 2023)

2. Joseph C. Winter, Tobacco Use by Native North Americans: Sacred Smoke and Silent Killer, University of Oklahoma Press, 2000, p. 4, http://books.google.com/books?id=UGI4hxx6mTQC; "Brief History and Culture of Tobacco," East West School of Herbology, June 2007, https://www.planetherbs.com/theory/brief-history-and-culture-of-tobacco.html; Emily and John Salmon, "Tobacco in Colonial Virginia," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, February 13, 2023, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/tobacco-in-colonial-virginia/; "The Land," Naval Weapons Station Yorktown, https://cnrma.cnic.navy.mil/Installations/WPNSTA-Yorktown/About/History/Mine-Depot/The-Land/ (last checked March 3, 2023)

3. Lois Green Carr and Russell R. Menard, "Land, Labor, and Economies of Scale in Early Maryland: Some Limits to Growth in the Chesapeake System of Husbandry, The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 49, No. 2, June 1989, p.413http://www.jstor.org/stable/2124072 (last checked October 29, 2011)

4. Gale, H. Frederick Jr., Foreman, Linda, Capehart Thomas, Tobacco and the Economy: Farms, Jobs, and Communities, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Economic Report No. 789. September 2000, p. 1; US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service "Quick Stat," http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/ (last checked October 29, 2011)

5. Tobacco and the Economy: Farms, Jobs, and Communities, p.1

6. "Burley tobacco belt stretches east," Southeast Farm Press, March 8, 2006, http://southeastfarmpress.com/burley-tobacco-belt-stretches-east (last checked October 26, 2013)

7. "Factory shows that Richmond is still a tobacco town," Virginia Business, September 27, 2013, http://www.virginiabusiness.com/opinion/article/factory-shows-that-richmond-is-still-a-tobacco-town; "Cigarette making still going strong in South Richmond," Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 30, 2013, http://www.timesdispatch.com/business/manufacturing/cigarette-making-still-going-strong-in-south-richmond/article_27bad786-788e-570a-b837-b008519c1c39.html (last checked October 26, 2013)

8. "Altria to close 2 tobacco facilities; some operations moving to Richmond," Richmond Times-Dispatch, http://www.richmond.com/business/ap/article_117a0cf6-1287-54a3-8ca7-eccdeab649cf.html; "China Dependent On Tobacco In More Ways Than One," National Public Radio, February 18, 2011, http://www.npr.org/2011/02/18/133838124/china-dependent-on-tobacco-in-more-ways-than-one (last checked October 28, 2016)

9. International Tobacco Growers Association, "Tobacco Types," http://www.tobaccoleaf.org/conteudos/default.asp?id=18 (last checked October 29, 2011)

10. "Tobacco and the Economy: Farms, Jobs, and Communities," United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Appendix 2, p. 37, November, 2000, (last checked June 19, 2018)

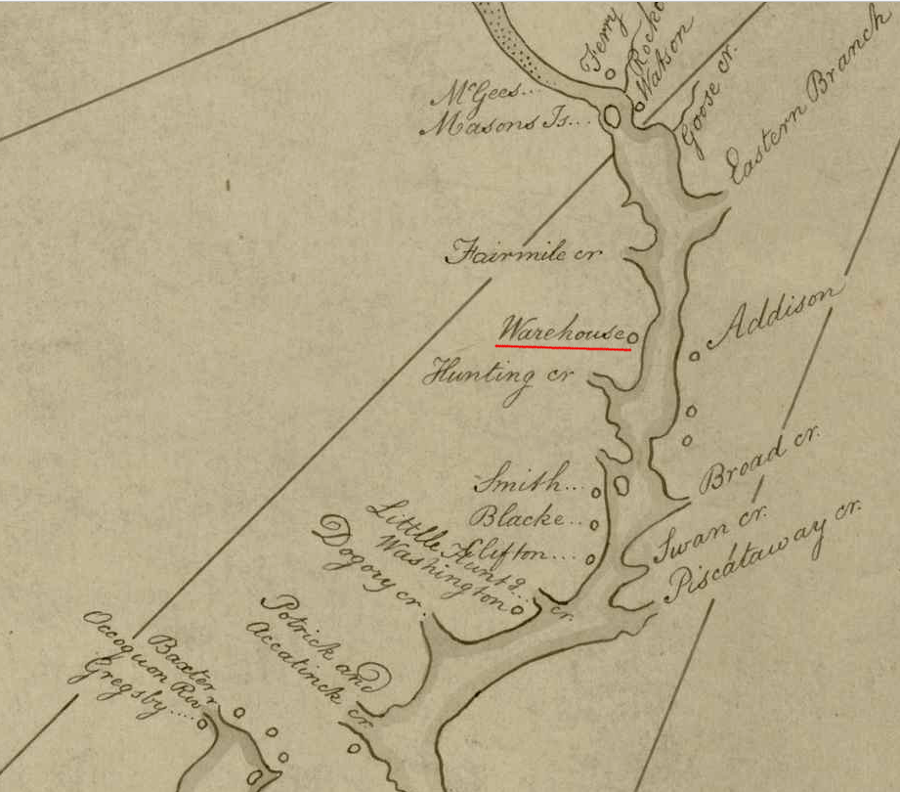

Peter Jefferson's 1747 map of the Fairfax Grant noted the Hunting Creek tobacco inspection warehouse

Source: University of North Carolina, "Early Maps of the American South," A Map of the northern neck in Virginia (by Peter Jefferson, Robert Brooke, Benjamin Winslow, Thomas Lewis, 1747)

Source: Library of Congress, Out from tobaccoland U. S. A. (1949)

Virginia Agriculture

Virginia Places